Racist housing policies have created some oppressively hot neighborhoods

Decades of redlining and other discriminatory practices reshaped urban landscapes in Minneapolis and elsewhere, leaving some areas 10 degrees hotter than others.

The blacktop burned Melodee Strong’s feet through her sneakers as she stood at the corner of Plymouth and Penn Avenues in North Minneapolis, gazing at the 250-foot-long “Black Lives Matter” street painting she and other artists were working on.

It was mid-July and brutally hot. By late morning, temperatures had soared to over 100 degrees. The paint dried so fast that Strong could watch as it crinkled into place, wishing she had worn thicker-soled shoes. “Unless we had astronaut shoes, or fireman’s boots, I don’t think anything would have worked,” she said.

Two months earlier, just a few miles south, George Floyd had been killed by a Minneapolis police officer. In response, Strong and the artists decided to paint the mural, and they intentionally put it here in North Minneapolis, a historical center of Black life in the city—and ground zero for some of its starkest racial disparities.

This particular spot holds another distinction: It’s one of the hottest neighborhoods in the city. Temperatures around here can be more than 10 degrees Fahrenheit hotter than the city’s cool areas, according to an analysis published earlier this year, putting at risk the health and safety of the neighborhood’s residents, about half of whom are Black.

This disparity is not an accident. The heat shimmering around Strong is at least in part the result of over a century of explicitly and implicitly racist and exclusionary city planning decisions at both the local and national level.

Such decisions have resulted in measurable differences in heat. A recent study found that in more than 100 American cities, neighborhoods that were “redlined” in the 1930s—deliberately discriminated against on racial grounds, in home loans and other economic support—are today, on average, about 4.7 degrees Fahrenheit hotter than un-redlined neighborhoods in the same city.

That means in formerly redlined neighborhoods, which are still primarily filled with Black and brown communities, families face heat stresses now that foreshadow the ones climate scientists say will strike the more affluent parts of Minneapolis and other cities decades in the future.

“Heat today is an indicator for what’s gone on in the past,” says Vivek Shandas, an urban planning expert at Portland State University and an author of the study, published in the journal Climate. Redlining and other discriminatory policies have shaped the distribution not just of cooling trees and hot pavement but also the location of freeways, factories, and other factors that affect health in today’s urban landscape, he says: “You pull that string and so many things unravel, decade after decade.”

Hot cities

Scientists have long known that features common to cities can make heat measurably worse. Two hundred years ago, an amateur climatologist in London found that thermometers he’d set up in the center of the city almost always measured warmer temperatures than ones from pastoral outer hamlets—the first evidence of what we now know as the “urban heat island effect.”

Today, researchers think of the heat island as more of an archipelago: In any city, hot spots appear where concrete and asphalt prevail, while cool zones emerge around trees, parks, or other open space.

Dark surfaces like paved roads or tar-covered rooftops readily absorb heat from the sun. They also tend to hold onto that heat more tightly than natural materials like loose dirt or plants. Big, densely clustered buildings do the same. Once heated up, they release the heat only slowly into the surrounding air like a hot, stale breath.

Trees and plants, on the other hand, cool cities down. Their leaves reflect away some incoming solar heat and shade the ground below. Their roots also suck water from the ground and eventually release it to the air in a process called evapotranspiration. The energy to vaporize the water comes from heat in the air, which leaves the left-behind air cooler.

But trees grow where they grow, and neighborhoods look how they look, because of choices made in the past.

This summer, young scholars in the predominantly Black Near North neighborhoods in Minneapolis saw the difference with their own eyes. Six days in a row, masks on, a group of students from the Liberty Community Church’s 21st Century Academy summer program piled into a van and drove away from their home base to different nearby neighborhoods.

They each held a worksheet prepared by Cyreta Odunuyi, one of the leaders of the summer academy. It posed a series of questions: What do you see in this neighborhood? How does that change as we drive into these other areas?

Near the church, they saw abundant pavement and few green spaces. But as they drove into the leafy, affluent Bryn Mawr neighborhood, just a few minutes away, they saw houses set far apart from each other, with wide swaths of lawn between them. Parents strolled beneath the verdant tree canopy with their babies.

Underlying the differences they saw, Odunyi explained to the scholars, is redlining.

Covenants, redlining, and their legacy

“Redlining” is a colloquial term for a practice introduced in the 1930s, as the federal government struggled to revive the U.S. economy during the Great Depression. Government leaders wanted to help homeowners who were facing default on their mortgages or otherwise wouldn’t be able to afford houses, so they developed a state-sponsored lending program—the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, or HOLC—that could issue mortgages.

The HOLC hired real estate agents to map areas within cities where loans would be “safe—” places where property values would stay high, protecting the government’s investment. At the time, the ethics code of the burgeoning real estate profession required them to maintain and promote neighborhood segregation in the interest of “racial harmony.” The HOLC maps were created with the explicit intention of keeping some neighborhoods white.

“Safe” areas, like Bryn Mawr in Minneapolis, were outlined in green and graded with an A. Neighborhoods that were considered risky were outlined in yellow (C, “Definitely Declining”), or red (D, labeled “Hazardous”). If just one African-American family lived in a neighborhood, it would be usually be redlined.

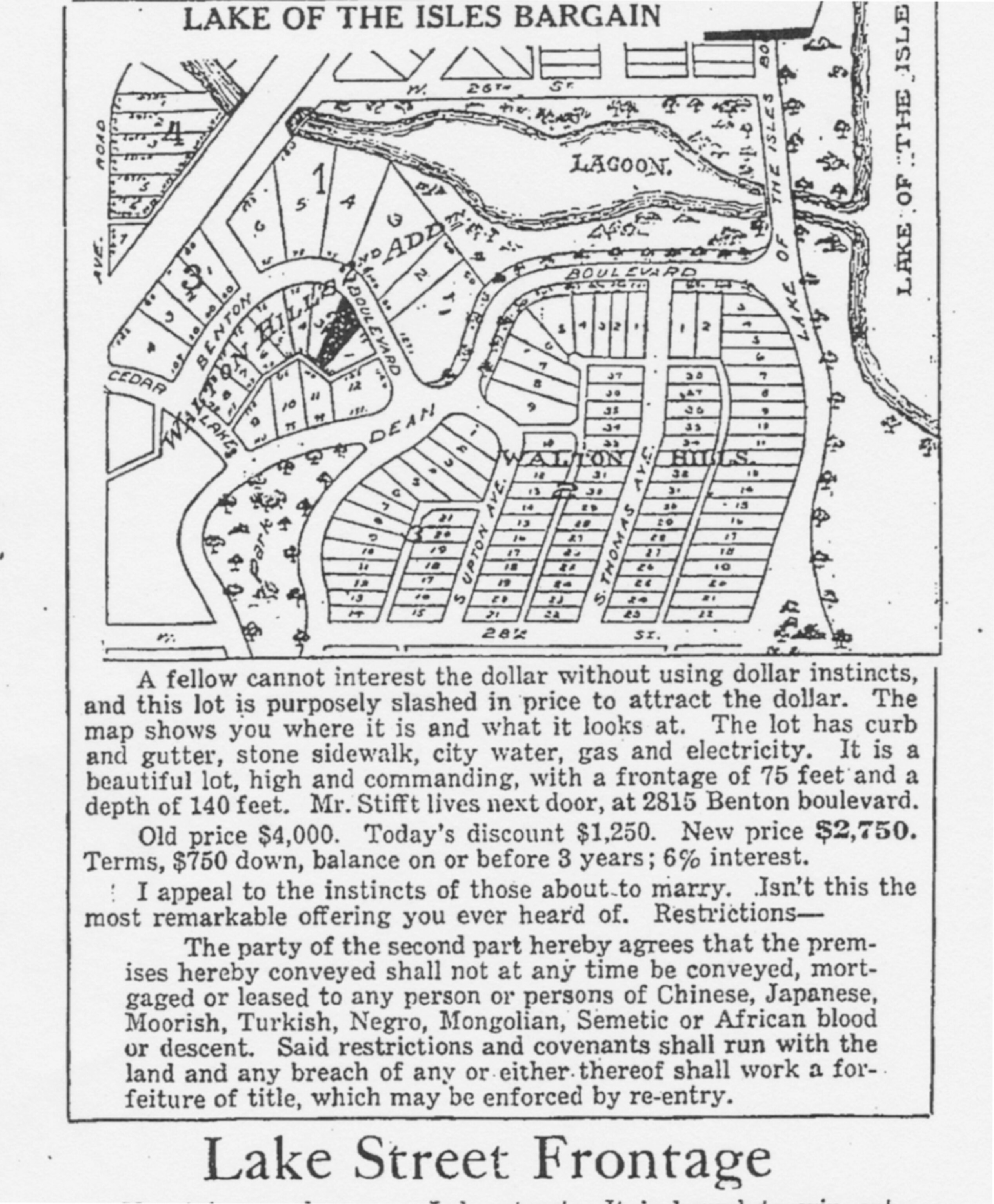

Before there was a national policy encouraging and enabling housing segregation, local-scale strategies had taken root. Racially explicit “covenants’ prohibiting a property’s sale to non-white buyers had proliferated across the country since the late 1800s. Minneapolis’s first covenant, from 1910, read unambiguously: “[These] premises shall not at any time be conveyed, mortgaged or leased to any person or persons of Chinese, Japanese, Moorish, Turkish, Negro, Mongolian or African blood or descent.”

Covenants were in use until 1968, when the Fair Housing Act made the practice illegal.

By then the damage had been entrenched for decades. In the early 20th century, Minneapolis, like many other northern U.S. cities, had only a small Black community—about 1 percent of the city’s population. But the families were scattered across the city, not centered in any one area. Only after the advent of racial covenants, redlining, and other discriminatory practices were they forced into a few narrow zones near the city center and denied the opportunity to buy property.

By the 1940s, those newly segregated Black neighborhoods had some of the lowest rates of homeownership in the country, at least in part because Black families were ineligible for federally insured loans and denied access to private credit. Over the following decades, as the Great Migration brought more Black families north, the disparities and the segregation grew. In Minneapolis, as in many other cities, the city’s funding for parks, neighborhood maintenance and infrastructure, schools, and more, went elsewhere.

A 'Rorschach test' of inquality

The indelible effects of racism influenced everything from the location of waste sites to school funding, says Kirsten Delegard, a historian at the University of Minnesota who led a massive project to map Minneapolis’s historical covenants and relate them to today’s racial disparities.

“We kept showing this map to different groups, and it was like a Rorschach test of their background and interests,” she says. Health experts, for example, noticed that the covenant-free, redlined areas of the map corresponded disturbingly well with the areas they knew had high asthma rates and low birth weights—conditions associated with exposure to air pollution and other environmental hazards. A local food expert saw that stands of fruit trees were abundant in neighborhoods where whites-only covenants had been common. In one of the most striking examples, Delegard recalls, a city council member exclaimed that her map of racial segregation looked just like a map of street tree cover.

“This is the base map that everything else is built on,” Delegard says. “Any other measure of well-being can be traced back to these restrictions.”

“Once you see it, you can’t unsee it, and it changes how you think and feel,” says Kevin Gilliam, a doctor who works in a clinic around the corner from the BLM street painting. It’s an easy pivot, he says, to couple this summer’s social unrest, the devastating effects of the pandemic on Black communities, and environmental justice issues.

“It is not a stretch of the mind or imagination to connect social ills with environmental disparities, housing disparities, and health disparities,” Gilliam says. “All these things can be traced back to the same roots.”

That includes heat. In formerly redlined neighborhoods, as the Minneapolis city council member had noticed, there are fewer trees and more pavement. Other factors, like the major freeways that snake through the center of the city, contribute as well—and their locations were also predicated on racist planning decisions. Built in the 1950s and 60s, as the Black population of the city grew, the freeways served to further isolate nonwhite communities. The pavement absorbs heat from the summer sun and radiates it to the surrounding neighborhoods.

Liberty Church and the site of the BLM street painting are both in areas graded “C”—not quite redlined, but historically they too had received little investment. In the short drive to Bryn Mawr, the young scholars crossed the physical reality of policies put in place over 100 years ago and reinforced over and over in the intervening years.

Heat will spread

Minneapolis has one of the largest temperature disparities between formerly redlined neighborhoods and those graded “A” in the 1930’s, according to the study by Shandas and his colleagues. But the researchers found a similar pattern in nearly every single one of the 108 cities they analyzed. Minneapolis, Portland, and Denver had the biggest differences, with temperature differentials over 10 degrees Fahrenheit.

“All these cities, when you look at them, it’s almost surgical,” says Jeremy Hoffman, lead author of the paper and chief scientist at the Science Museum of Virginia. “You look along one little road and you can know exactly where the redlining happened.”

According to the Centers for Disease Control, heat kills more than 700 people each year in the U.S. One recent study suggests the actual number may be nearly 10 times larger.

Heat is dangerous far below the threshold at which it is directly lethal. It exacerbates many health complications, like hypertension and heart disease. Many common medications also disrupt the body’s ability to control its internal temperature. Air quality often plummets when temperatures rise, leading to more pollution-related illness.

Just a few degrees of extra heat during an extreme event, or over the longer term, can push people past health thresholds into dangerous territory, says Catherine Harrison, a public health specialist on Minneapolis’s Emergency Preparedness team. Experts estimate that some 3,000 deaths occur annually in the U.S. because of moderate heat.

Climate change will increase the risks. And residents of northern cities, which were not built with extreme heat in mind, may be particularly vulnerable. For example, the 1995 Chicago heat wave killed over 700 people, primarily elderly people of color who lived without air conditioning in the hottest parts of the city, where temperatures were likely higher than the officially recorded values.

An analysis from the Union of Concerned Scientists says the number of days in Minneapolis with a heat index of above 100 degrees Fahrenheit—the kind of day Melodee Strong painted in—could increase to 20 by the middle of the century, and over 40 by the end of the century. (Between 1960 to 1990, on average, only two days a year were that hot.) The city is expecting average summer temperatures to rise by nearly eight degrees Fahrenheit by the middle of the century.

“By 2025, we’re going to be seeing a lot more heat waves and days above 90,” says Eric Wojchik, a planner with the Twin Cities’ Metropolitan Council, which recently assessed the area’s climate vulnerability. He pauses. “2025 is not that far away.”

In Minneapolis, residents of the city’s hotspots are already experiencing the heat that is coming for everyone. Residents of the cool areas, who are primarily white, are living in very different heat-landscape—one that can be double-digits cooler on a hot day, according to a University of Minnesota analysis.

This disparity in experience has clear consequences in terms of social action and policy, says Harrison. Even the really hot days aren’t yet that bad for many white residents, she says.

“I think, when white comfort is impacted, when the ‘out there’ issues become more proximal to them—that’s when we’ll see serious action occur” to address both local heat issues and climate change, Harrison says.

Currently, there is no funding for climate change-related heat adaptation in the city, says Kelly Muellman, the sustainability program coordinator for the city. Nor, adds Harrison, is there funding to assess the risk systematically, meaning that heat-related illnesses and deaths are likely underestimated.

A respite isn't always available

For those living in the hottest neighborhoods, the issues are here, now, and especially acute because of the COVID-19 crisis. The pandemic was certainly on Liberty pastor Alika Galloway’s mind at the beginning of summer. In late June, she and her husband, Pastor Ralph Galloway, knew that the summer scholars would soon be arriving.

To follow guidance on COVID-19, the Galloways wanted the kids outdoors as much as possible, But they also wanted to shield them: from both gun violence and overzealous policing in the neighborhood, especially as police backlash against protests ramped up, and from the pandemic itself, which was ravaging Minneapolis’s communities of color at rates more than three times higher than in white communities.

The Galloways also worried about the heat.

To minimize their own carbon footprint, they had for years resisted installing air conditioning. But the conditions in June and July were too concerning, so they gave in.

“We really didn’t want to,” says Galloway. “But this is our children, our babies. You have to make this tragic moral choice, because you’re in this destructive heat, in order to get them some relief so they can learn and rest, because their homes aren’t cool either.”

The Galloways, their young scholars, and everyone else in the hot zones of the city are living at the edge of the future, in a world shaped by the country’s racist past and present and partially shut down by COVID-19. For Sam Grant, director of the Minnesota chapter of 350.org and a longtime advocate for environmental justice, the intersection of all these crises has rendered some things crystal clear.

“It’s two kinds of heat we’re facing,” Grant says. “The heat of racism and of temperature. To have both those at the same time, in a global pandemic: It is an ugly, ugly moment. But I think—I hope—it is causing a reopening, as well.”