Today, a piece of land in the southern Brazilian state of Paraná is called the Pterosaurs’ Cemetery because of the hundreds of fossilized pterosaur bones found in the ancient basin. So when paleontologists working there unearthed a new fossil creature with a horny, parrot-like beak, they at first assumed it was yet another flying reptile.

Instead, researchers were shocked to learn that they’d found a whole new species of toothless dinosaur. Even stranger, the animal belongs to a group called the ceratosaurians—almost all of which were carnivores.

“The fact that we now have this toothless dinosaur means we have to rethink the evolutionary loss of teeth for all dinosaurs in this group,” says Alexander Kellner, a paleontologist on the team that found the fossil and director of the National Museum of Brazil. “It’s a discovery that’s going to change the way we think and what we know about these animals.”

The fossilized skeleton, described in the journal Scientific Reports, belongs to a new species called Berthasaura leopoldinae that lived between 80 million and 70 million years ago during the Cretaceous period. The formal name is a nod to Bertha Lutz, an important Brazilian scientist who championed women’s suffrage, and Maria Leopoldina, an Austrian who became Empress of Brazil and was a defender of the natural sciences.

The moniker makes Berthasaura one of only a few dinosaurs that pay homage to women with a newly named genus.

“It’s an important message that could inspire new female scientists to join these fields, and particularly the study of dinosaurs,” says Aline Ghilardi, a paleontologist at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte who was not part of the study team.

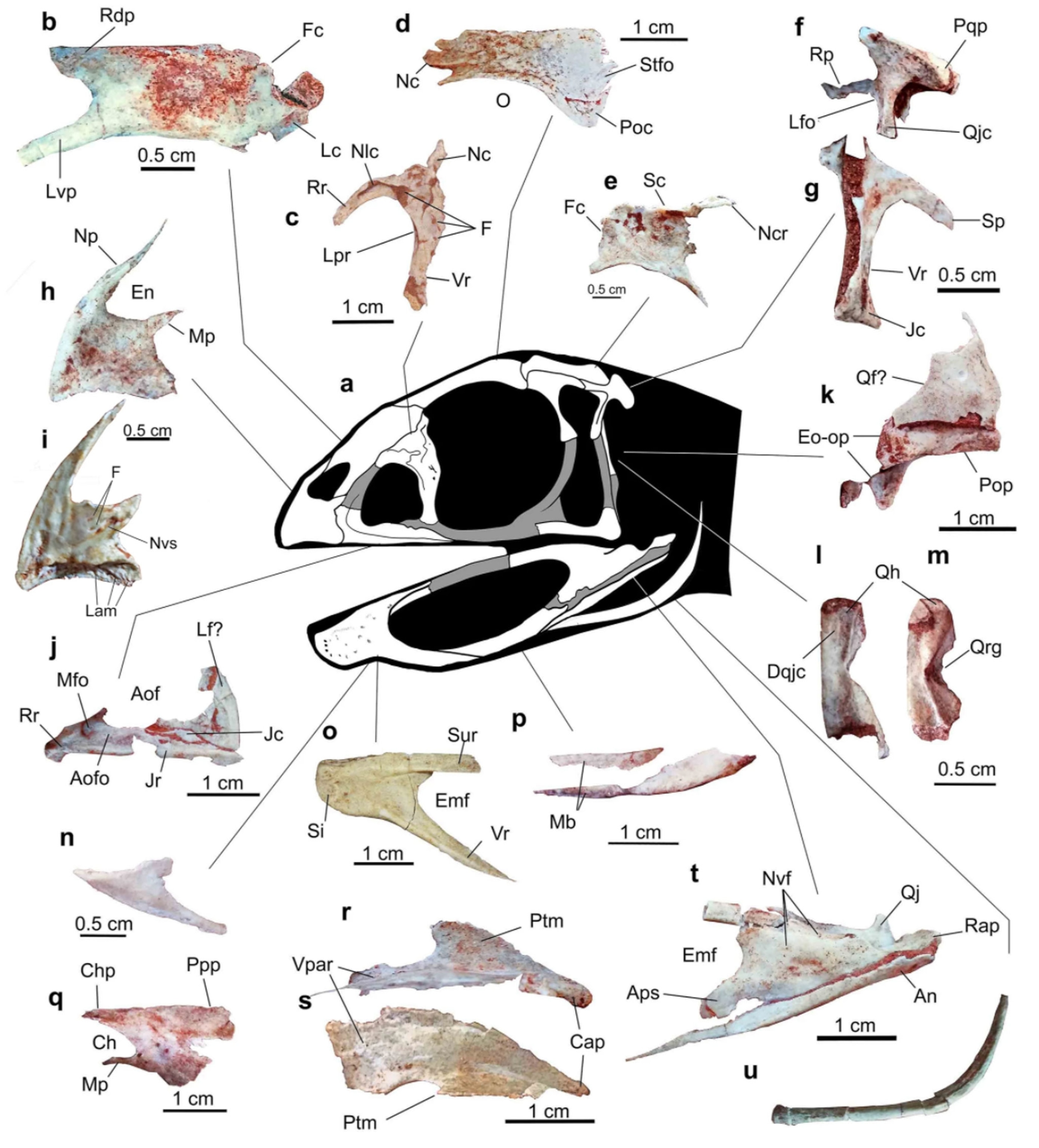

She also notes the value of the skeleton being near-complete and extremely well preserved. Between 2011 and 2014, researchers from Brazil’s National Museum and the University of Contestado Paleontological Center collected parts of its skull and jaw, spine, pectoral and pelvic bones, and forelimbs and hindquarters.

“It’s something that’s always welcomed in paleontology,” Ghilardi says, “because it helps us better understand the relationships among species.”

Family ties

When the researchers who found Berthasaura leopoldinae realized the dinosaur in front of them had no teeth, they immediately thought of Limusaurus inextricabilis, a toothless theropod discovered in northwestern China. Limusaurus lived sometime between 161 million and 156 million years ago, during the Jurassic period. Based on fossils of both adults and juveniles from the same species, scientists know that this ceratosaurian dinosaur lost its teeth as an adolescent and didn't grow another set.

Berthasaura, on the other hand, never had any teeth at all.

The skeleton found in Paraná is of a young animal, and “on the upper arch [of the mouth] it was clear there were no teeth,” says Kellner. “There was a plate of bone where you would expect teeth. But we wondered, were there teeth on the lower arch? So we isolated that part of the material and used a CT scan to confirm that this animal really never had any teeth.”

The team wants to find out what made the species evolve the way it did. For Kellner, it’s all about diet. While there’s no hard evidence yet, he thinks the dinosaur may have been an herbivore—making it unlike other theropods, which are almost all carnivores. (Also read about a vegetarian cousin of T. rex found in Chile.)

“Why would it lose its teeth if it needed to cut through meat?” he says. “This is adaptation. Because at some point in the past, an ancestor had teeth and lost them.”

But not everyone—including other members of his team—agrees. For Geovane Alves de Souza, another National Museum researcher, it’s too early to confirm what Berthasaura ate. He suspects it might have been an omnivore capable of tearing at meat with its beak, the same way modern crows and ravens do.

“An absence of teeth alone doesn’t confirm eating habits,” he says. To suss out an ancient animal’s diet, scientists usually turn to a handful of techniques and tools. One involves examining stable isotopes left by food on fossilized teeth—impossible in Berthasaura’s case. Another creates a precise 3D model of the animal’s cranium to see how it would have moved while biting, tearing, or chewing possible food items. But because Berthasaura’s bones were found disarticulated, that can’t be done either.

“It’s something we have to figure out, because we weren’t expecting it,” says Kellner. “It’s the first dinosaur without teeth in Latin America.”

Can you dig it?

The team hopes the place where Berthasaura was found will provide them with more clues.

The area called the Pterosaurs’ Cemetery used to be a Cretaceous desert, and several other species—including pterosaurs, lizards, and another theropod—have already been discovered there, all with remarkably intact skeletons. Kellner chalks up the excellent preservation of the bones to a natural phenomenon that likely happened several times after their deaths.

“We imagine there were a lot of pterosaurs and a few dinosaurs—which were rarer—that died over time,” he says. “And then there were flash floods, which can happen in the desert, that collected everything they crossed paths with, including dead animals, and brought them to a basin, where they accumulated and were preserved.”

He and the rest of the team hope to uncover further details about Berthasaura by finding more members of the species in the region. For now, though, the pandemic and a lack of funding have prevented them from returning to the dig site.

In the meantime they are preparing to open a visitors’ centers in Rio de Janeiro while the National Museum, which suffered a devastating fire in September 2018, is being rebuilt. The fossilized skeleton and a 3D reproduction of Berthasaura, among other items, will be on display for those who want to see them up close.

“This type of dinosaur shows, once again, how we can bring science to the population,” Kellner says. “Our country has so many important [fossil] deposits. It’s not just this one, where this dinosaur was found. What we need now is support to get out there, back in the field, so we can continue our research.”