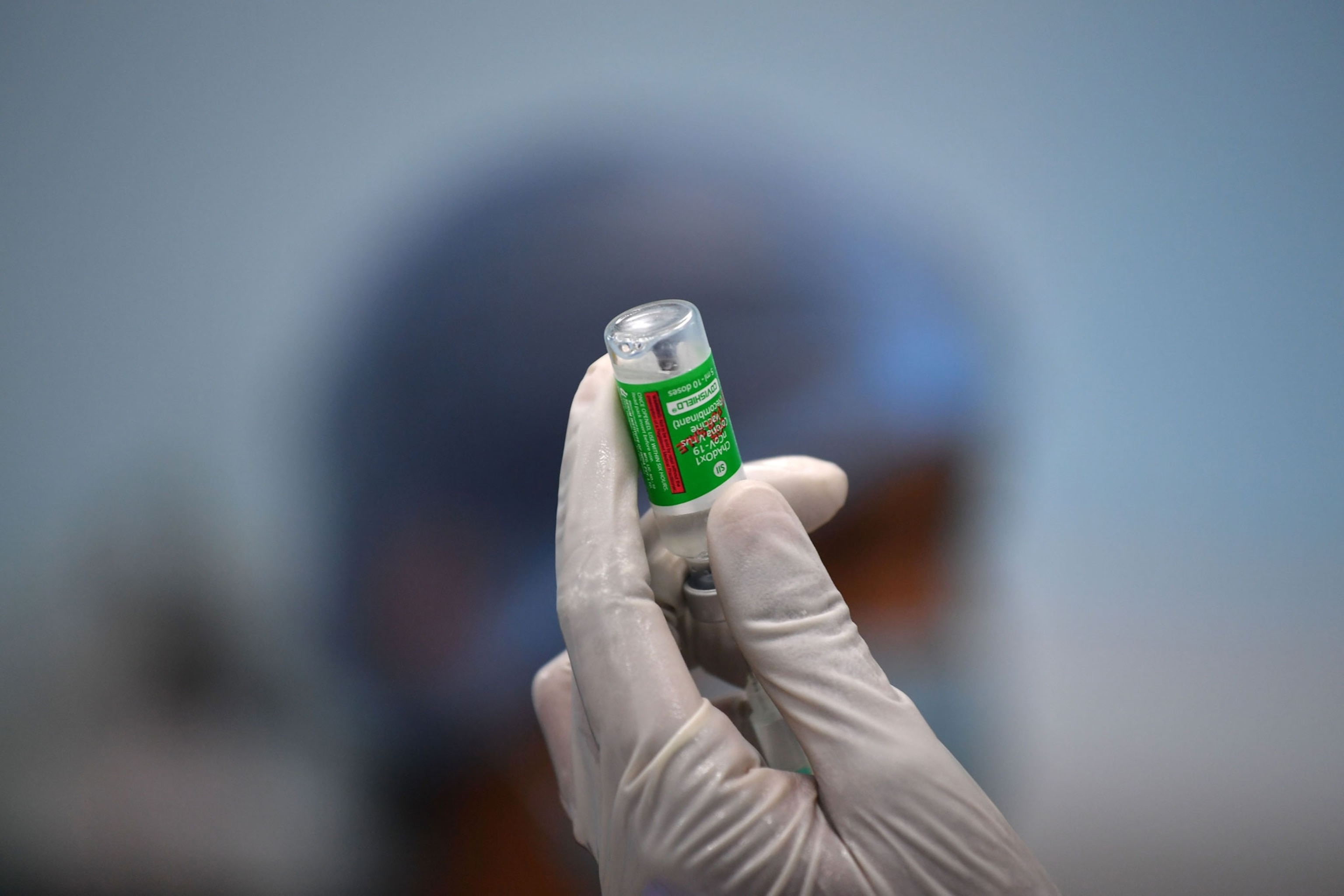

AstraZeneca’s vaccine has 76 percent efficacy—slightly lower than the interim results announced Monday

The company confirmed the vaccine’s safety after it was accused of releasing incomplete data that a federal panel called “outdated and potentially misleading.”

After damning accusations from federal health officials, AstraZeneca released results from the primary analysis of the completed U.S. phase three trial showing that its vaccine was 76 percent effective at preventing symptomatic COVID-19. That is 3 percentage points lower than the results announced Monday, which were based on incomplete trial data that only extended until February 17.

The results were even better in adults 65 years and older; the vaccine had an efficacy of 85 percent. Most important, the vaccine was 100 percent effective at preventing severe COVID-19 and hospitalization and there were no reports of serious side effects, like those reported in Europe during the past month. AstraZeneca vaccinations were briefly halted in several European countries last week after a few people died from a rare blood clotting condition.

Although the vaccine is not as effective as the ones from Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna, it is safe and effective. The results are good news for AstraZeneca. In a highly unusual departure from what is usually a confidential process, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases revealed that AstraZeneca had been reprimanded for issuing an overly optimistic press release describing the results of its COVID-19 vaccine trials in the United States.

NIAID released the statement early Tuesday morning after the Data and Safety Monitoring Board, an independent group charged with keeping an eye on clinical trials, notified AstraZeneca about its concerns that the company chose to release data that presented the most favorable efficacy number for their vaccine. According the New York Times, the DSMB warned the company, “Decisions like this are what erode public trust in the scientific process.”

The DSMB had met with AstraZeneca multiple times in the past two months, according to the Washington Post, and had seen vaccine efficacy numbers that ranged between 69 and 74 percent at preventing symptomatic COVID-19. The board advised the company to include those numbers in the press release. But the company only mentioned that the efficacy was 79 percent. AstraZeneca responded Tuesday, stating that those results were based on an “interim analysis” but that they were consistent with the primary results, which they released early Thursday morning. The company will submit the data for Emergency Use Authorization in the U.S.

The back and forth between AstraZeneca and the Data and Safety Monitoring Board may not have an immediate impact in the U.S., where three other vaccines have been authorized and are being used to vaccinate the population. But Eric Topol, a physician and professor of molecular medicine at Scripps in La Jolla, California, believes that AstraZeneca’s behavior could harm the vaccination campaign. "This really undermines the ability to roll out this vaccine,” says Topol. “It has a rippling effect across all the vaccines and gives fodder to those people who don't trust vaccines."

The primary results are good news for regulators in the United Kingdom, the European Union, and the World Health Organization who are trying to restore faith in the AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine.

Public health officials will be able to use the results to reassure the public that the vaccine is safe, and there is no indication that the shot can cause severe blood clots.

“If there was a strong association, a clear signal would immediately become very obvious,” says Edward Jones-Lopez, an infectious disease specialist with Keck Medicine of USC, who is one of the investigators in the ongoing clinical trials of the AstraZeneca vaccine in the U.S. “But it is only when you have millions of people—which is an order of magnitude here greater than in the clinical trials—that very rare side effects become apparent.”

But public health experts worry that it could be hard to restore shaken confidence in the vaccine’s safety at a crucial stage of the pandemic. New infections are rising again in many European countries driven by new variants; the continent recorded more than 1.2 million new cases last week. Further disruptions in vaccinations could cost more lives.

“Once you scare people, it’s hard to unscare them, so we need a careful review of these cases,” says Paul Offit, a physician and director of the Vaccine Education Center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, who is also a professor of vaccinology at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. “Sometimes, things occur in clusters and are meaningless. So we need to put this in context.”

In the U.K., where more than 10 million people have received the AstraZeneca vaccine, there haven’t been any reports of these extremely rare clots. Overall, AstraZeneca has received 37 reports of blood clots out of more than 17 million people vaccinated in the EU and the U.K. as of March 8. In a statement, Ann Taylor, the company’s chief medical officer noted, “the number of cases of blood clots reported in this group is lower than the hundreds of cases that would be expected among the general population.”

The safety data from the clinical trials of the vaccine, which encompassed tens of thousands of volunteers, didn’t pick up these adverse events either.

Why Germany paused vaccinations

Still, questions remain. The initial suspension in Germany was prompted by a report from the Paul Ehrlich Institute, the country’s agency in charge of vaccine safety, about a serious blood clotting disorder in seven patients that was fatal for three of them. Overall, a total of at least 13 patients in five nations, all of whom were between the ages of 20 and 50 and previously healthy, reported these symptoms; seven of them have died. All of these cases occurred between four and 16 days after vaccination with AstraZeneca’s COVID-19 vaccine.

Some experts believe the incidence of this rare blood disorder is significantly higher than would be expected by chance. Called severe cerebral venous thrombosis, the syndrome has manifested in unusual ways. Patients have suffered from blood clots, often in the brain. At the same time, their blood platelet counts are low; platelets normally help with clotting and this depletion of clotting factors in the blood has led to internal bleeding. “It’s a very special picture” of symptoms, Steinar Madsen, medical director of the Norwegian Medicines Agency, told Science. “Our leading hematologist said he had never seen anything quite like it.”

Scientists don’t know whether the vaccine caused this syndrome, or what the mechanism would be if the shot had triggered these side effects.

“To see all these cases is worrisome,” says William Schaffner, an infectious disease specialist and professor of preventive medicine at the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine in Nashville. “We would call this a signal, not a conclusion, but a signal that needs to be investigated further. There’s smoke here and maybe even some fire. We have to distinguish between things that are causally related with things that are coincidental.”

On Thursday, Norwegian scientists, who studied three Norwegian health workers affected by this very rare condition, stated they believed these reactions were, in fact, caused by the vaccine. Their explanation is that the vaccine caused the immune system to over-react, leading to the formation of antibodies that then caused the platelets in the blood to form clots. At the same time, these antibodies caused the opposite effect. By depleting blood platelets, which are essential for coagulating the blood, it also caused internal bleeding.

“There is nothing in the patient history of these individuals that can give such a powerful immune response,” Pal Andre Holme, chief physician from the University Hospital of North Norway, told the Norwegian national newspaper VG on Thursday. “I am confident that the antibodies that we have found are the cause, and I see no other explanation than it.”

Despite that, later that day, Emer Cooke, head of the European Medicines Agency, said, “This is a safe and effective vaccine.” Its benefits far outweigh the risks, noted Cooke, especially given the harm if people are deprived of access to a vaccine and get COVID-19. Even if the worst-case scenarios are eventually proven true, she added, and it turns out that in a small number of individuals this vaccine can trigger fatal blood clots and internal bleeding, for most people the vaccine would still be safe and effective. The agency will continue to investigate the links but given the EMA’s greenlight, EU nations plan to resume their vaccination campaigns.

In the U.S., a similar but less serious blood disorder, called immune thrombocytopenia, has been seen in at least 36 people who have received either the Pfizer or Moderna vaccines, but the U.S. Food and Drug Administration said the incidence of this condition isn’t any higher in vaccinated people than in those who are unvaccinated.

“We’re vaccinating older people,” says Schaffner. “Even if we didn’t vaccinate, medical events occur in the older population every day.”

Also, it isn’t unheard of for vaccines to trigger rare blood disorders. Offit notes that the measles-mumps-rubella vaccine can cause thrombocytopenia in about one child per 30,000 doses.

How the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine works

The AstraZeneca vaccine is different from both Pfizer and Moderna vaccines in that it uses a modified cold virus to smuggle DNA fragments encoding parts of the SARS-CoV-2 virus inside human cells to trigger an immune response. In contrast, the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines use what’s called mRNA technology to stimulate an immune response. AstraZeneca and the University of Oxford collaborated to devise and test their version of the coronavirus vaccine. Clinical trials in the U.K., Brazil, and South Africa found the vaccine had an efficacy of 82.4 percent when two doses are given between four and 12 weeks apart.

The surface of the SARS-CoV-2 virus is dotted with what are called spike proteins that it uses to latch onto, and then enter, human cells. This spike protein became a convenient target for vaccine makers. For the AstraZeneca vaccine, scientists spliced the gene that instructs the virus to build the spike protein into the DNA of a modified cold virus that affects chimpanzees. These cold viruses—carrying the spike protein gene—can infect human cells but don’t replicate or cause disease.

When the AstraZeneca vaccine is injected into humans, these cold viruses latch onto to proteins on the surface of the cell, and like a tiny cargo ship, they deliver the DNA into it. The human cell’s machinery then uses the DNA instructions to manufacture the spike proteins that alert our immune system that a foreign intruder is present.

When the immune system detects the spike protein it reacts as if the body were under attack from the real coronavirus. Immune cells that fight off infections and make antibodies swing into action. By latching onto the coronavirus spike proteins, the antibodies prevent infection by blocking the spike proteins attaching to cells. This prevents the virus from entering the cell.

A life saver for poor countries?

The AstraZeneca vaccine, which the British-Swedish company had produced in a collaboration with Oxford University scientists without the goal of making a profit, had been hailed as a life saver for developing countries and is key to the WHO’s campaign to inoculate poor and middle-income countries. It is inexpensive to produce, it can be churned out quickly in large quantities, and it can be kept in a conventional refrigerator for up to six months without having to stay frozen like the more fragile Pfizer and Moderna vaccines.

The AstraZeneca vaccine has not yet been approved in the U.S. But it has been granted conditional marketing authorization or emergency use in more than 70 countries across six continents. Plus, the WHO’s recent emergency use listing should accelerate its access to up to 142 countries through COVAX, the WHO-led initiative that is designed to ensure even poor countries have access to the vaccines.

“The worry is that there will be countries that will get upset about this,” says Vanderbilt’s Schaffner. “In the developing world, they’ll say, Gee, you’re giving us the second-rate vaccine.”

Disruptions in the rollout could seriously undermine the global effort to curb the pandemic because the company committed to providing a large number of shots to underserved countries.

“We’re only as strong as the weakest country out there,” says Offit of the University of Pennsylvania. “This was going to be an inexpensive, easily stored vaccine, and given to the world. I’m afraid people are not going to want to use it for the wrong reasons. If there is a safety issue, we need to find out because there is a lot riding on this.”