Here's Where We Might Reach the Limits of Science

There are some things we may never know—about time, consciousness, the universe, and how to predict the roll of the dice.

When Donald Rumsfeld, U.S. Secretary of Defense under George W. Bush, famously referred to the “unknown unknowns” affecting foreign policy at a press briefing in 2002, he was mocked for what seemed a nonsensical utterance. But when it comes to the universe, British mathematician Marcus du Sautoy readily admits that there are many things we may never know, from the nature of time to how human consciousness works. In his new book, The Great Unknown: Seven Journeys to the Frontiers of Science, he probes the mysteries we have yet to solve.

Speaking from his home in Oxford, England, du Sautoy explains why, despite all the advances in science, we still can’t predict the roll of the dice, how the latest discoveries about the brain represent a new golden age of science, and why he wants to send one of his twin daughters into the outer reaches of space.

You explore the idea of the unknown through seven “edges.” Talk us through that idea—with an example. Why “edges”?

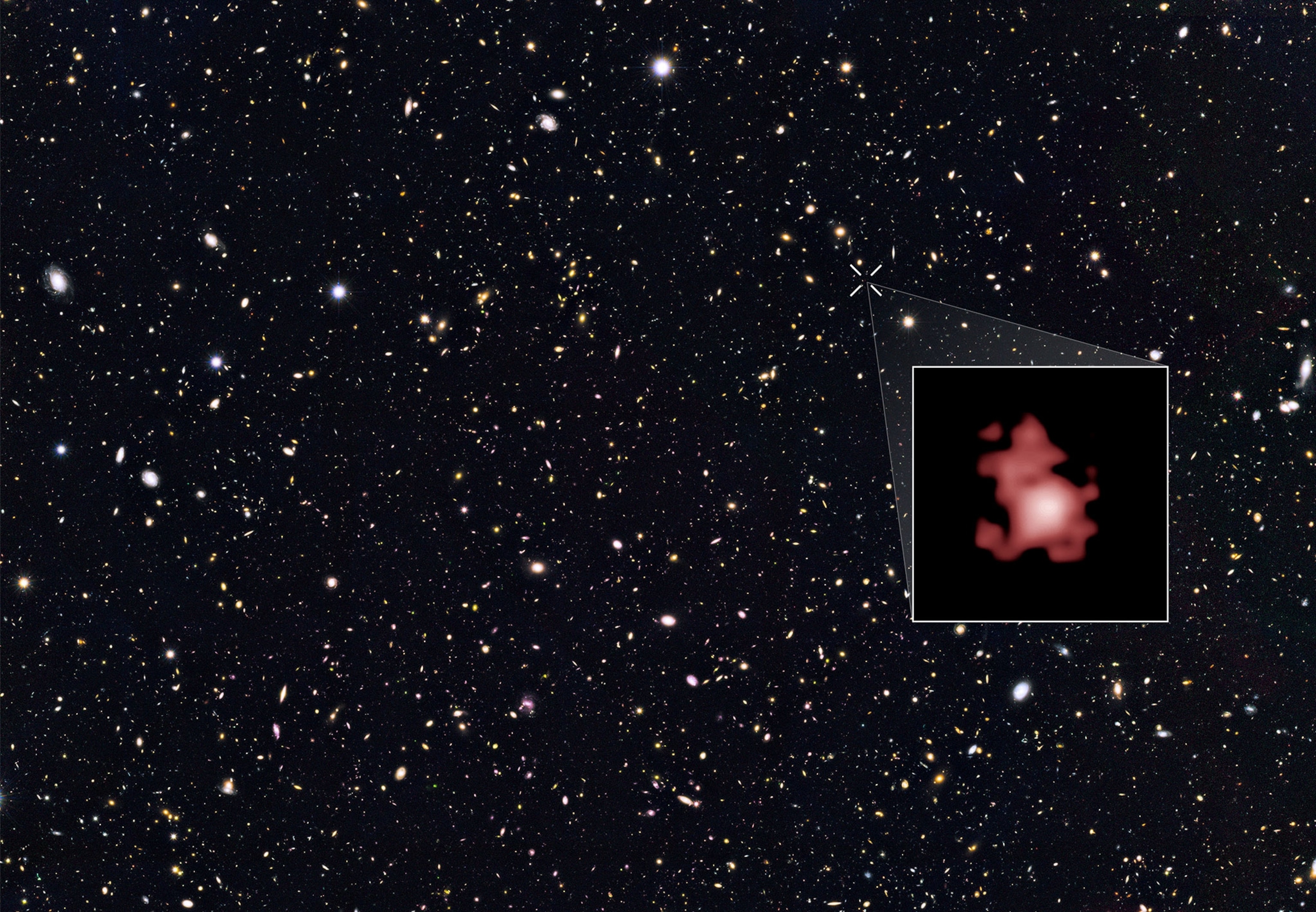

What I’m trying to do in this book is to identify the limits of science. How far can science get us and what is beyond that edge which science will not be able to know? I quite like the feeling of an edge being a place where you can reach but you can’t go beyond. Take the universe edge, which is a question about whether we could ever know if the universe is infinite. Could we ever know that?

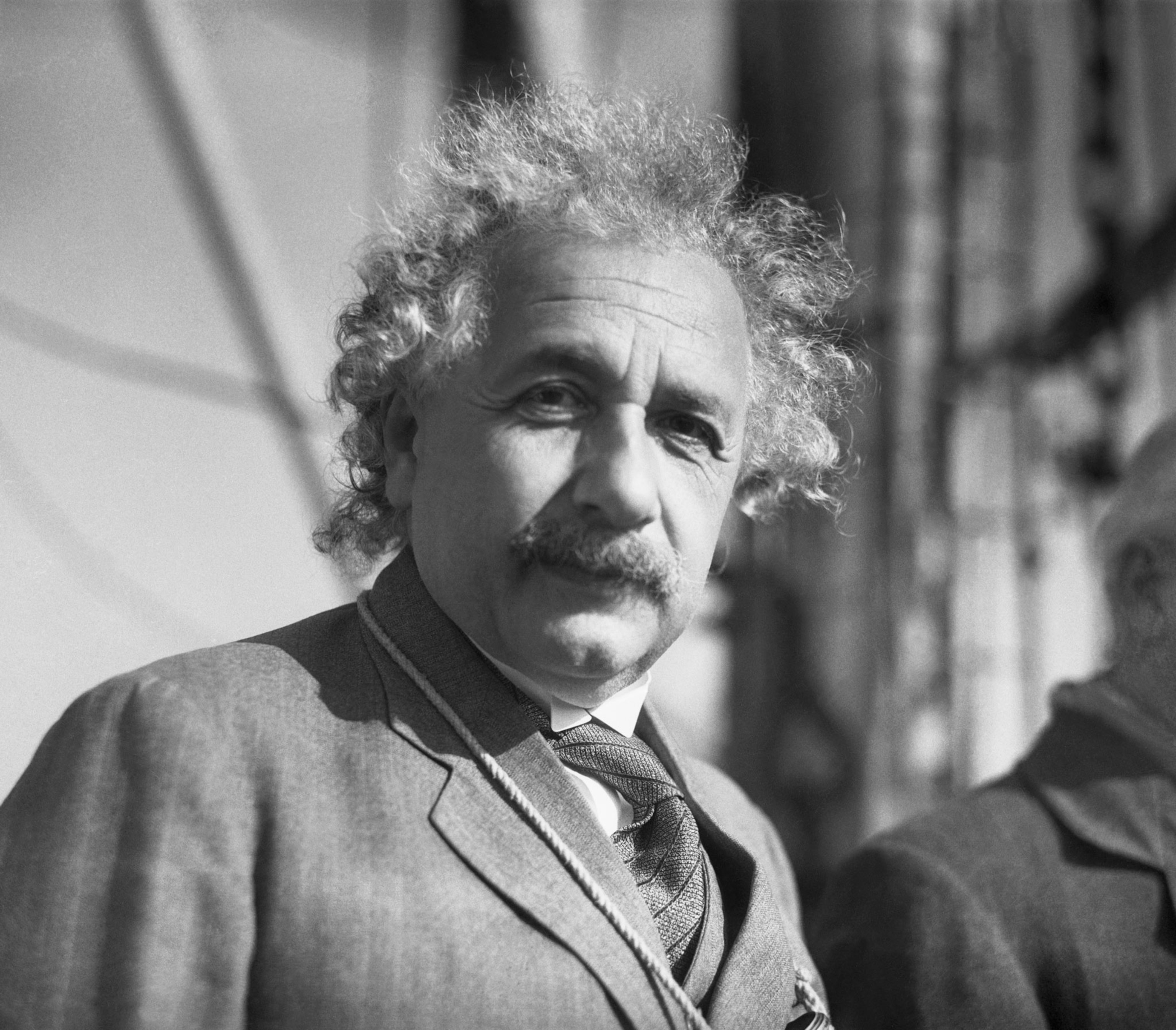

There is an almost literal edge there because the revelations that Einstein made, that information can’t travel faster than the speed of light, means that there’s a bubble surrounding us, an information bubble beyond which we cannot receive any information because there hasn’t been time for anything beyond that edge to reach us.

One of the most shocking discoveries in my journey to this edge is that because our universe is accelerating in its expansion, things are being pushed over this edge faster than the edge is growing! So we’re losing information rather than gaining more information. So much so that, in the future, there’ll come a point where all the galaxies have gone over this edge.

Tell us about the Las Vegas dice you keep on your desk—and what it can tell us about probability.

I was drawn to mathematics as a subject because I hankered after certainty and the power of mathematics to prove things with 100 percent certainty. Post-Newton, we seem to have the tools to maybe look into the future and know with certainly what might happen. But why have those tools failed to help us to predict, for example, how dice will fall?

I went off to Vegas to try and make some money, using my mathematical tools, and realized how sometimes they can be very impotent. We’ve understood in the 20th century that, even if we have a deterministic universe, following mathematical equations may not ever be good enough to know what’s going to happen next. Chaos theory tells us that our intuition of a good approximation of the present should help us have a good approximation of the future. But this is actually false. Small errors can explode into large differences in predictions.

Science has usually been antithetical to the idea of God. Talk about your conversations with the British quantum physicist John Polkinghorne, and how your journey to understand the unknown changed your views about God.

I kind of rejected conventional religion because once you learn the scientific story, it seems to offer better explanations about the way the universe works. But when I took over from Richard Dawkins as the Simonyi Professor for the Public Understanding of Science, the question of my own beliefs kept coming up.

People were intrigued to know, am I going to be a militant atheist like Richard? Certainly, I signed up to rejecting the idea of a supernatural intelligence, which is the conventional view of what God is. But there was something interesting in the idea of knowledge that will always transcend the ability of humans to comprehend.

Quite a few scientists I talked to on this journey turned out to have some sort of religious angle, like John Polkinghorne, who trained as a quantum physicist but halfway through his career got ordained as a priest. Polkinghorne is a theist, who believes his God acts in the world. So I was intrigued, as a serious scientist, what’s the science being used to express this action?

One of the unknowns of the world comes from quantum physics, which says that the future is not determined by the present. I wondered whether Polkinghorne might see that as an expression of the action of his God in the world. Weirdly, he went for chaos theory as the way his God acts in the world. [Laughs]

To explore your fifth “edge” (time) you imagine sending one of your twin daughters off into space. What was the idea behind that—and will we ever be able to fully understand time?

It’s a classic consequence of Einstein’s discoveries about the nature of time and its connection to gravity and acceleration. We know that if we send something off to a large gravitational field, time will slow down, which is equivalent to accelerating something. So, if I sent one of my twin daughters into outer space and accelerated her back again, her time will have gone slower than her twin on Earth, with the extraordinary result that she might come back and discover that her twin sister is 80 years older than her. [Laughs]

This is one of the important components of the film Interstellar. They realize that going into a gravitational field, like a black hole, has a cost in terms of time. They want to return to see their children and they know that any time spent near a large gravitational field will slow their time down. It’s beautifully played out in that film.

Einstein already began to question whether we really know what time is. We thought time was absolute. Newton certainly thought time was ticking at the same rate everywhere. But today there’s real questioning about whether time even is a fundamental thing in the universe. Maybe it’s one of these strange things called emergent phenomena: It’s actually our interaction with the universe that gives us a sense of something flowing.

Human consciousness is another of your great unknowns. Tell us why understanding consciousness remains such an intractable problem—and how you conducted experiments on your own brain.

This is one of the most exciting edges, partly because it is furthest from my own subject of mathematics. Philosophers have said for decades that consciousness is a question that, by its nature, is almost protected from being answered scientifically because it is so personal. How can I ever know that your consciousness—your sense of pain or feeling of the color red—is anything like mine? We use the same names for it and I might even be able to scan your brain and see that very similar electrical chemical activity is happening in your brain to mine, but that still doesn’t answer whether your conscious experience is anything like mine. My wife has synesthesia. She has a sense of color when she looks at letters and numbers. And I certainly don’t have that kind of conscious experience. As Descartes said, “The one thing I am sure about is my own consciousness.”

Today, the ability to look inside the brain represents a new golden age of science. It’s like Galileo with his telescope. Suddenly, we saw things in the universe that we never dreamt of. Now we have “telescopes,” like the EEG and MRI, which allow us to see the brain in action. The most exciting revelation was how my own tools of mathematics might be helpful in understanding the nature of the brain. The experiments I did myself about sleep showed that we can analyze the brain’s networks and see the different mathematical character between the awake brain and the sleeping brain. That that can be captured mathematically was one of the most exciting revelations of this whole book.

There is much talk of artificial intelligence at the moment. Do you think a computer will ever be able to fully replicate human consciousness? And how soon?

Yes, I do. For instance, the little chatbot app I downloaded to my iPhone is trying to answer Alan Turing’s challenge: Could you create something that is responding in such a way that you cannot know whether it’s a human or a machine responding? I talk to it, and it talks back to me using this thing called “machine learning” to learn from every experience to make it appear more human.

The analysis that Giulio Tononi is doing is showing how you might be able to piece together a network that can be regarded as having become conscious, that it has a sense of itself. Does that mean we might be able to download our own consciousness because we could see the information behavior of our brain and move that to another physical system? If it’s mimicking what’s happening in my brain, does that mean it’s actually feeling what it’s like to be me?

John Polkinghorne talks about the idea of information never being lost. He believes our souls are encoded information in the universe, and that there is a Resurrection because quantum physics gives him a way of saying that the information about what makes me me, never gets truly lost—even when I die and get burned in a crematorium!

And now for more important matters: As well as being an acclaimed mathematician, you are an Arsenal fan and a keen amateur player. What role does soccer have in your life—and in society, in general?

It’s always been really important in my mathematical journey to do other things as well, because that often is the place where I’ll have my best ideas, when I’m not actually at my desk thinking, like doing sport or playing music. One of the things that has benefitted me in my journey is having lots of stimuli from different disciplines. I spend a lot of time talking to artists about their practice, and find that often helps to inform what I’m doing.

For me, football is a game of chess when it’s played well, which is why I support the Arsenal, because at their best, they play the game in an extremely tactical way. I see it structurally; it’s like geometry in motion. When I’m watching the Arsenal, that’s what I’m appreciating, and when I’m playing I’m trying to put that into practice, not always successfully. [Laughs]

When asked about my religion, in order to put a bit of distance between me and Richard Dawkins, I playfully admitted that Arsenal was a bit like my religion. But there’s a serious element to that, too. Religion helped bind communities together in an urban environment like London. And I’ve found that football plays a powerful role in giving people a connection and bond across culture and class. The element of singing communally is also an amazing experience, like singing in a choir.

You say at the end of the book, “It is important to recognize that we must live with uncertainty, with the unknown, the unknowable.” Can you expand on that thought for us?

I have a slightly schizophrenic relationship with the unknown. It’s what gets me up in the morning to do my mathematics. Yet I’m slightly terrified there might be things that will always be beyond my knowledge. Maybe the thing I’m working on now doesn’t have a proof within my system of mathematics, and therefore I’m on a futile journey.

That’s why science must be in partnership with things like the arts and humanities, because they are our best tools for venturing into the unknown. Stories are a fantastic way to explore different possibilities. Often those stories are what becomes the spark for the next scientific revolution.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

Simon Worrall curates Book Talk. Follow him on Twitter or at simonworrallauthor.com.