The quest to engineer a silk that’s stronger than steel

It already exists in the natural world. Now, thanks to breakthroughs in genetic engineering, scientists have created “supersilk.” And it’s poised to upgrade far more than our clothing.

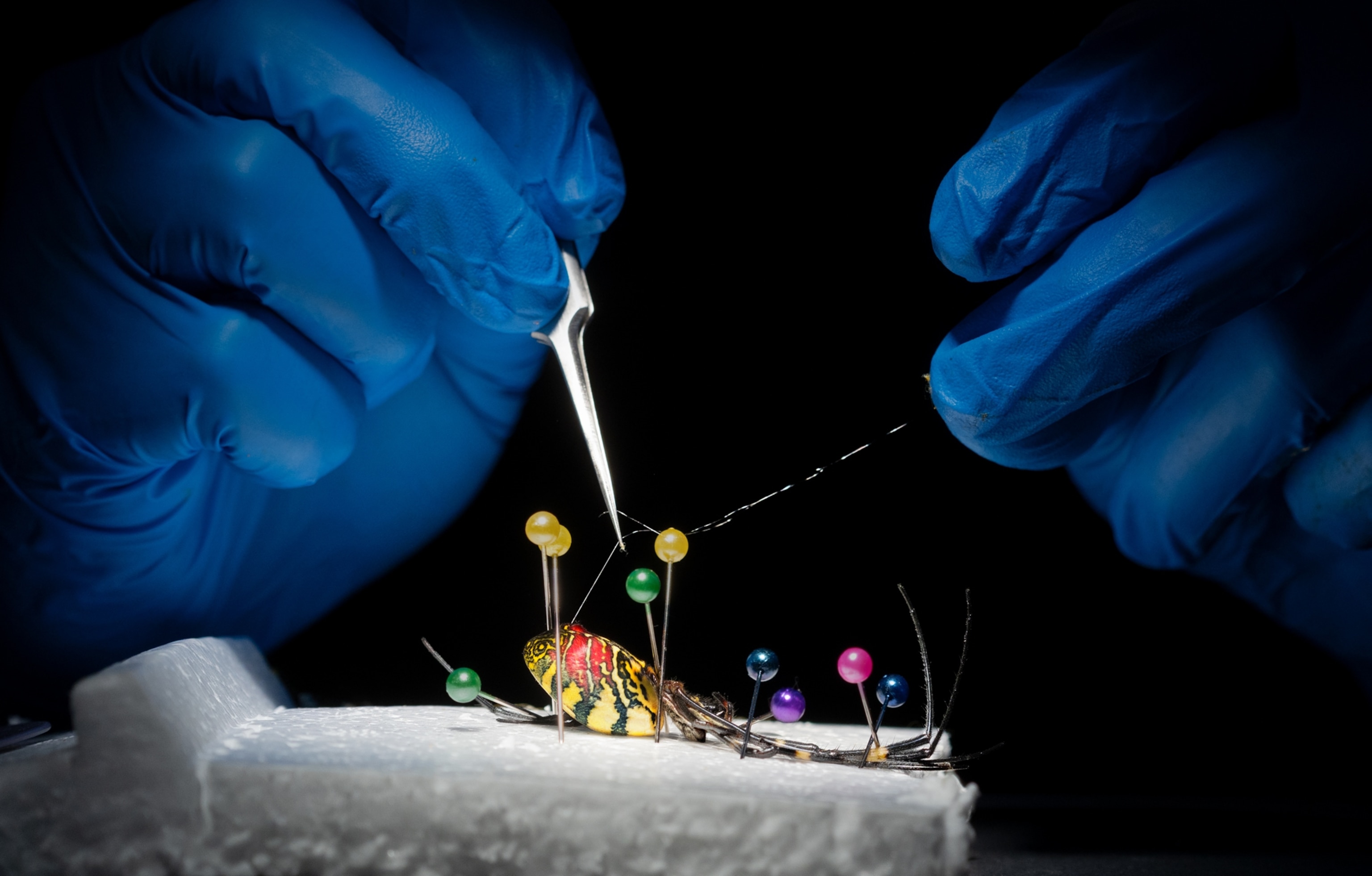

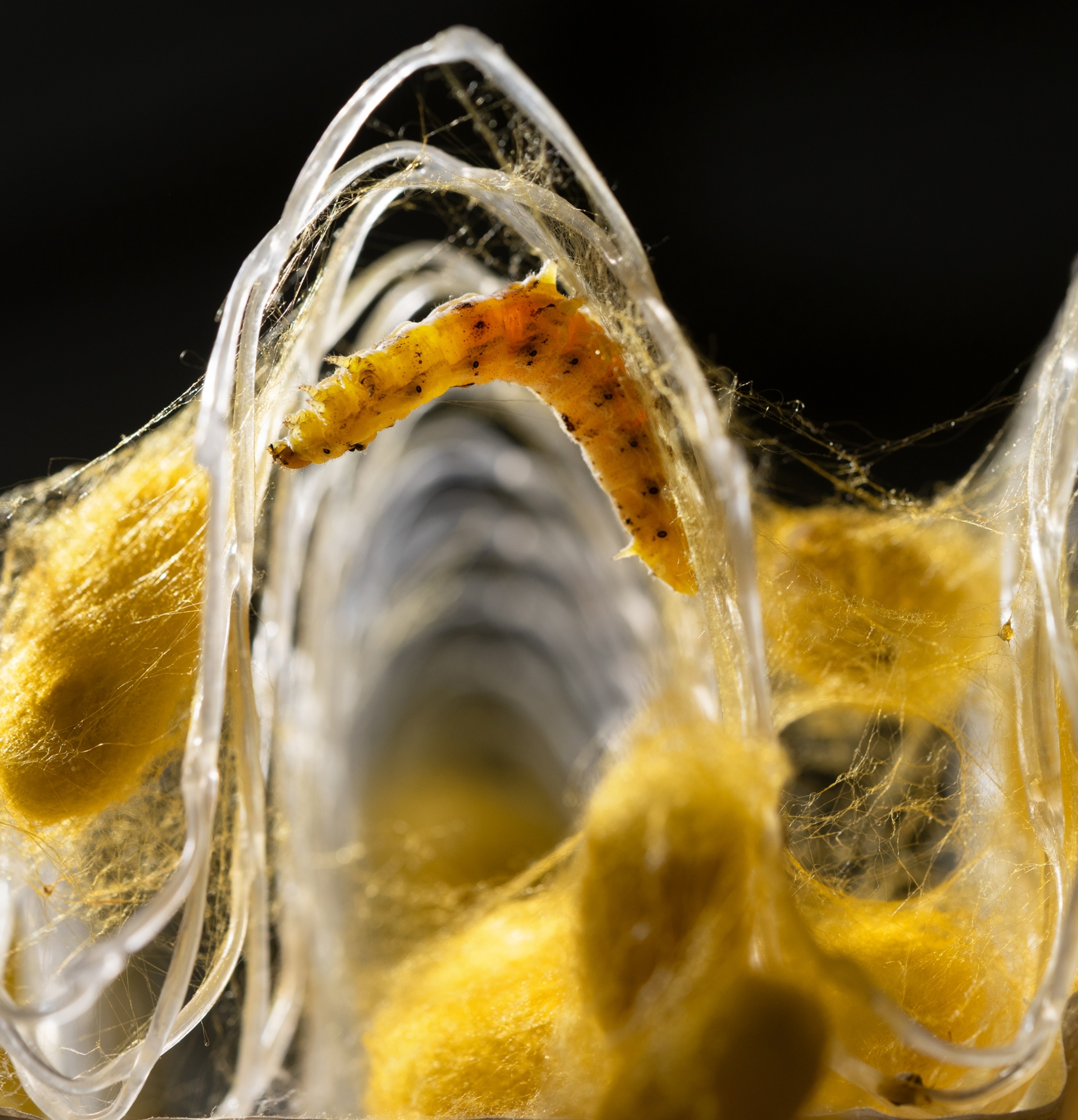

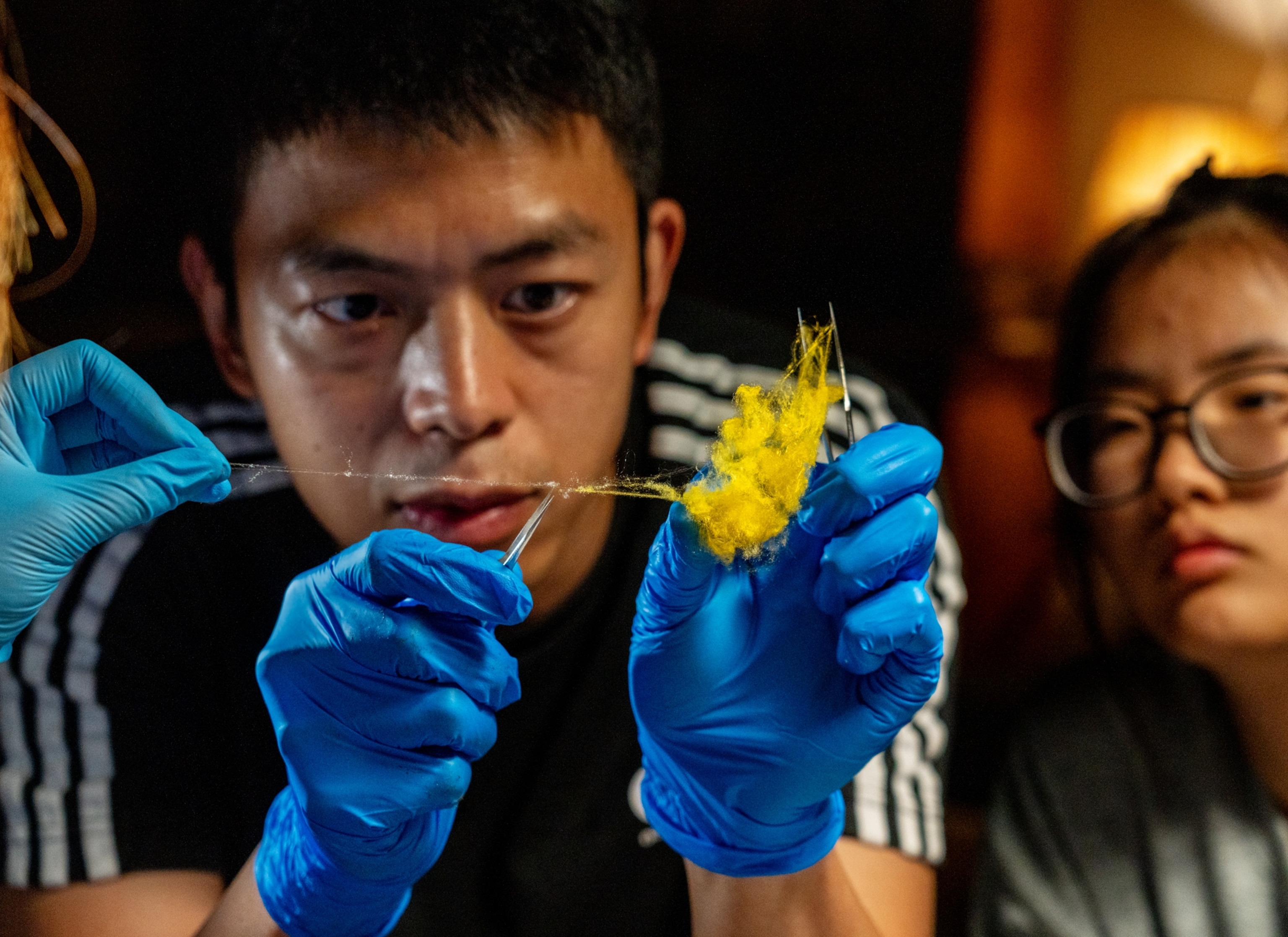

Somewhere in Michigan, 10,000 silkworms are spinning the future of supermaterials. They labor in the thick air of a warm, humid warehouse, pulling a sticky white strand from a gland in their face and weaving it into a cocoon the size of a grape. Since they were first domesticated in China thousands of years ago, their silk has been used to make the world’s finest fabric. But these silkworms aren’t like the millions that came before. They are spinning spider silk, or something close to it.

Pound for pound, spider silk, which has tantalized scientists for decades, combines strength and elasticity unlike anything else, natural or artificial. Five times stronger than steel by weight but completely organic, it’s “the stuff of superheroes,” says Fiorenzo Omenetto, director of the Silklab at Tufts University in Massachusetts. It exists in the same rarefied space as graphene and Kevlar, human-made creations with similarly extraordinary physical properties. But those can require synthetic chemicals to manufacture. Spider silk could do what they do, possibly better, and organically. That, in turn, has led to a steady stream of hype: Spider silk, if mass-produced, could unlock everything from improved bulletproof vests to ultra-light jet planes to next-generation vaccine delivery—if only we could crack the code. Spiders, though, are cannibalistic when forced to live together, making them neither domesticable nor easily scalable.

But in the past few years, everything’s changed. Those spider silk–spinning silkworms, all genetically modified, live at the Lansing, Michigan, research center of biotech firm Kraig Biocraft Laboratories. Kraig is just one of several companies around the world that have made breakthroughs in manufacturing spider silk. Or a very close analog. Those silkworms can’t quite match spider silk’s superhero-level physical properties just yet, but there is enough spider gene in the mix to give their silk fibers special qualities. Other companies have charted a different path—one less reliant on worms munching mulberry leaf cake—but with the same goal. “The goal is to mimic, and eventually surpass, the performance of natural spider silk, and then push it toward real-world applications,” says Wenbo Hu, a spider silk expert at Southwest University in central China. “We’re getting incredibly close.”

For the first time, the long-hyped supermaterial dubbed “supersilk” seems to be real. But the start-ups and genetic engineers who’ve spent years (and millions of dollars) pursuing this holy grail are now having to reckon with a question they’d been able to ignore in the quest for supersilk at scale: Once you make a supermaterial, what do you do with it? The answers, it turns out, aren’t as obvious as they’d imagined.

Spider silk is, by any measure, one of nature’s most miraculous structures. Large orb weaver spiders have been known to build webs that trap birds and bats. It may take a simple swipe of the human hand to brush through a spiderweb in the woods, but a hypothetically massive web with strands the thickness of a pencil could stop a 747 in flight.

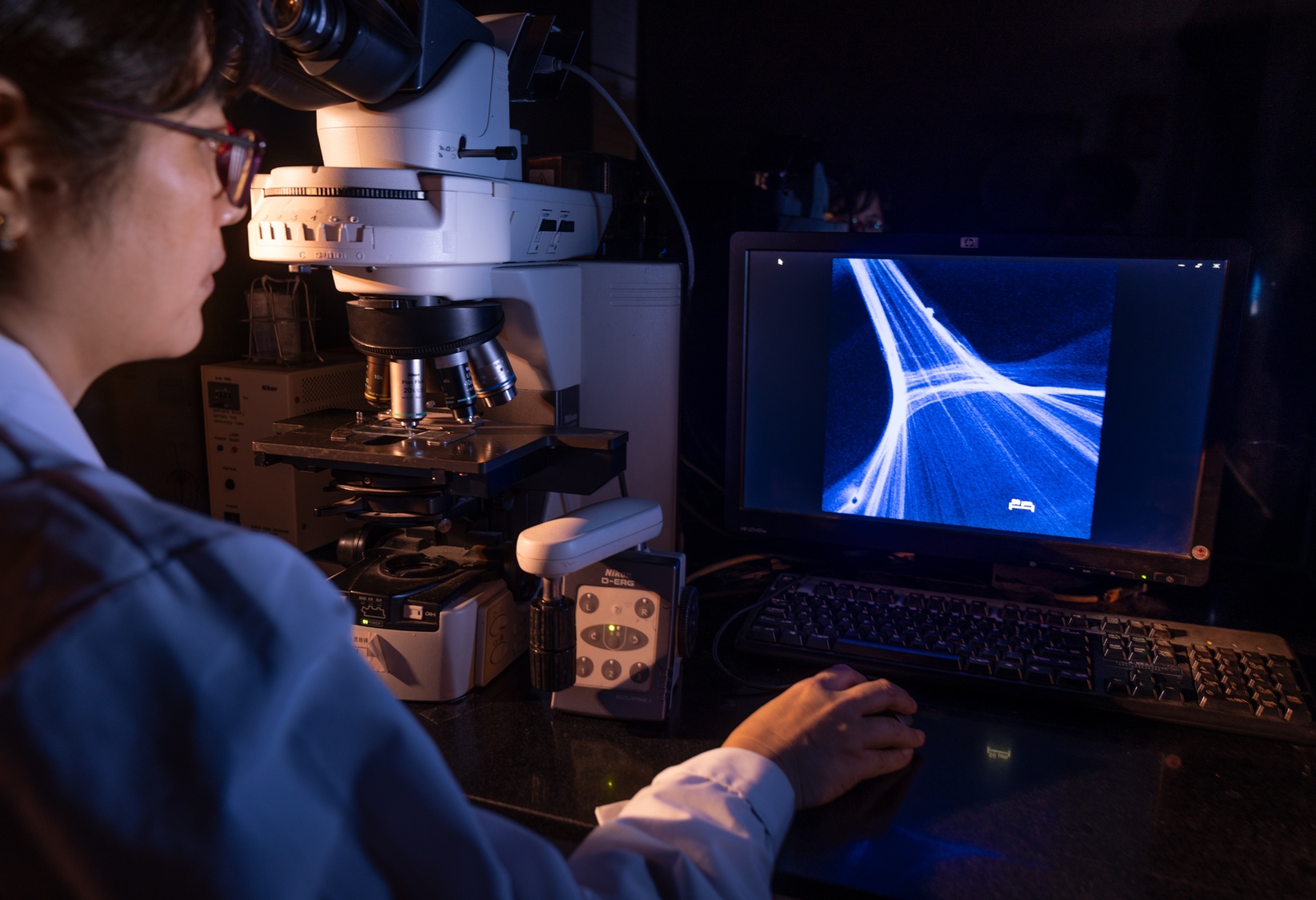

Spider silk’s seemingly magical capabilities derive from two singular factors: special proteins known as spidroins, and the way those spidroins are spun into intricate fibers. The spidroins are composed of thousands of amino acids in a long chain, mixing both positive and negative electrical charges as well as hydrophobic and hydrophilic sections, allowing them to stretch like an accordion while wrapping tightly around each other. Spiders then bundle those proteins into a cabled matrix of fibers that cling to each other so tenaciously that almost nothing can break them. Thrashing insects don’t stand a chance.

(How spider silk is one of the most versatile materials on Earth.)

Spider silk’s potential has been apparent for centuries: Ancient Greeks and Romans applied webs as wound poultices, while Solomon Islanders used web silk as fishing lures. But the first attempt to commercialize the material didn’t start until the late 1800s, when Jesuit missionaries stationed in Madagascar took note of the island’s golden orb weaver spiders and the prolific amount of silk they produced.

With the help of local children, the missionaries devised a system to immobilize the spiders and coax about 500 yards of silk from each. All that effort yielded a stunning golden yellow bed canopy that made a stir at the 1900 Paris Expo—but not much more. The process was too labor-intensive, and the spiders had a nasty habit of eating each other.

But spider silk continued to inspire. Why settle for the physical limits of cotton, wool, or regular silk when better options merely required ingenuity? In the 1930s, inspired by the architecture of silk, DuPont developed nylon, the first commercially viable synthetic fiber. Kevlar fiber arrived in 1966, its strong lattice of hydrogen bonds making it nearly unbreakable. Graphene, whose one-atom-thick sheets of honeycombed carbon make it the strongest material in the world, was created in 2003.

But while these synthetic fibers have revolutionized multiple industries, from clothing and cookware to aerospace and electronics, they’re dogged by their artificiality. They don’t degrade, they require harmful processes to manufacture, and in some cases they can burden the world—and our bodies—with toxic compounds and microplastics. For that reason, scientists have long dreamed of producing comparable materials out of organic proteins. Spider silk has always beckoned as nature’s finest model. But, given their ornery, individualistic natures, spiders were always likely to be cut out of the mix.

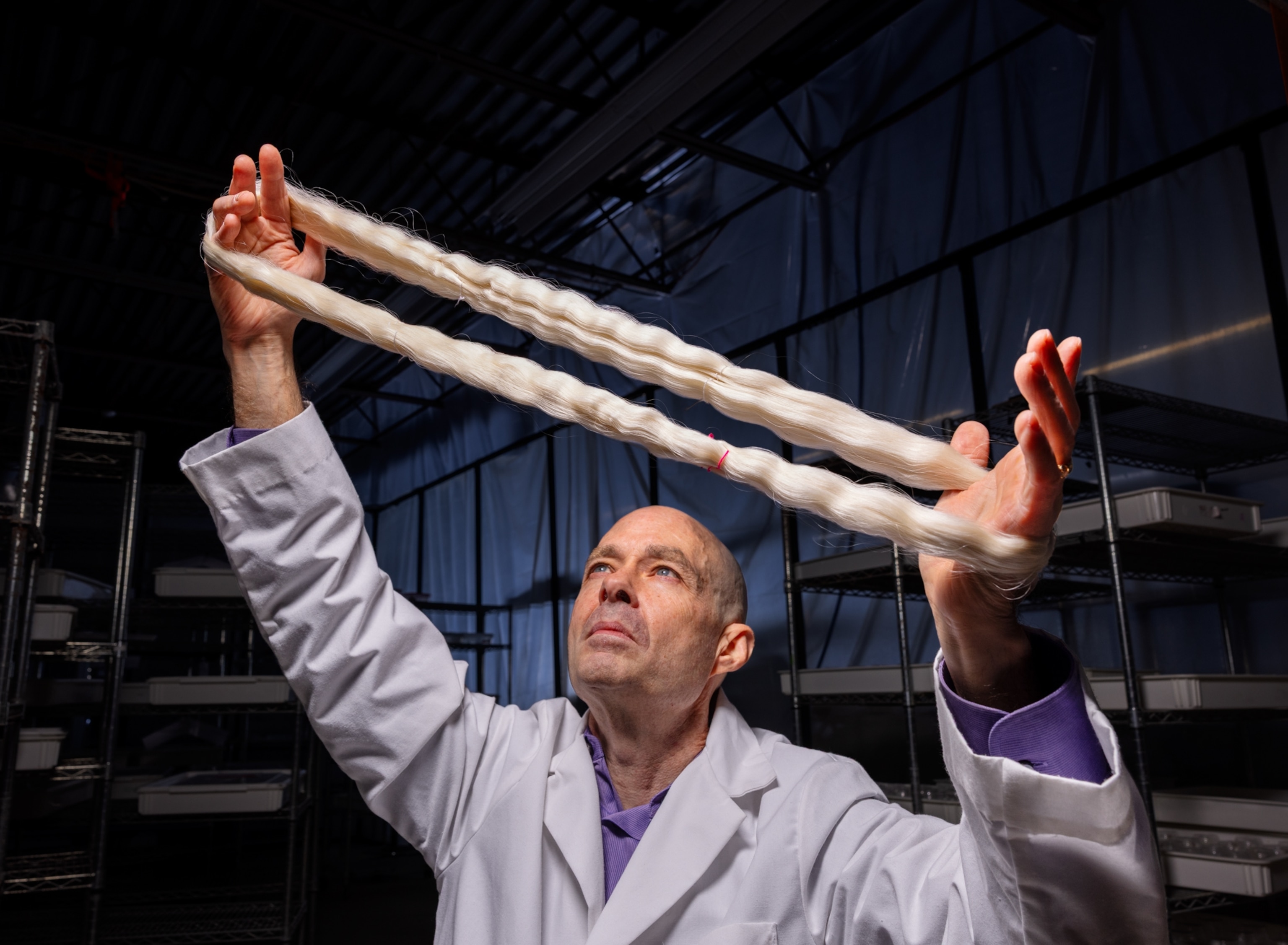

Efforts to create spider proteins without the spider began in earnest in the 1990s, according to molecular biologist Randy Lewis, then at the University of Wyoming. At first, he and his team eyed E. coli as a potential host. Their thought process: If you could engineer the bacteria to produce spidroins as part of their regular metabolism, you could cultivate them in a fermentation tank, as if you were brewing beer, then separate the spidroins from the mix, spin them into fibers, and voilà: spider silk.

That failed. Bacteria are so tiny that they struggle to produce comparatively huge proteins—and even when they do, they can’t mimic spiders’ intricate physical weaving process. Lewis turned to goats as possible spidroin producers, via their milk. And then alfalfa and silkworms. Nothing worked. The gene-editing tools of the time were cumbersome, and neither Lewis nor the other researchers pursuing genetically modified–organism spider silk could engineer a host to make enough protein.

Then technology came to the rescue: CRISPR-Cas9 arrived in the early 2010s. With the ability to rewrite genes at will in living organisms, finding hosts for spider silk became easier. The new technology “significantly improved the expression level of spider silk protein,” according to Chengliang Gong, a transgenic silkworm expert at Soochow University, near Shanghai. In 2023, Chinese researchers were able to coax full-length spider silk from a transgenic silkworm for the first time. The material had six times the toughness—the measure of a material’s capacity to deform without breaking—of Kevlar.

For Kraig Biocraft Laboratories, the new advances in genetic editing unlocked the ability to engineer worms with just enough spidroins to make a spider silk analog without hampering the worms’ productivity. According to Kraig founder and CEO Kim Thompson, the company’s latest silk is a big step forward. “This material is not gonna stop a 747,” he says, “but it’s better than regular silk. It’s stronger and more flexible.” It’s not quite spider silk, but it is supersilk. And most important, it’s scalable.

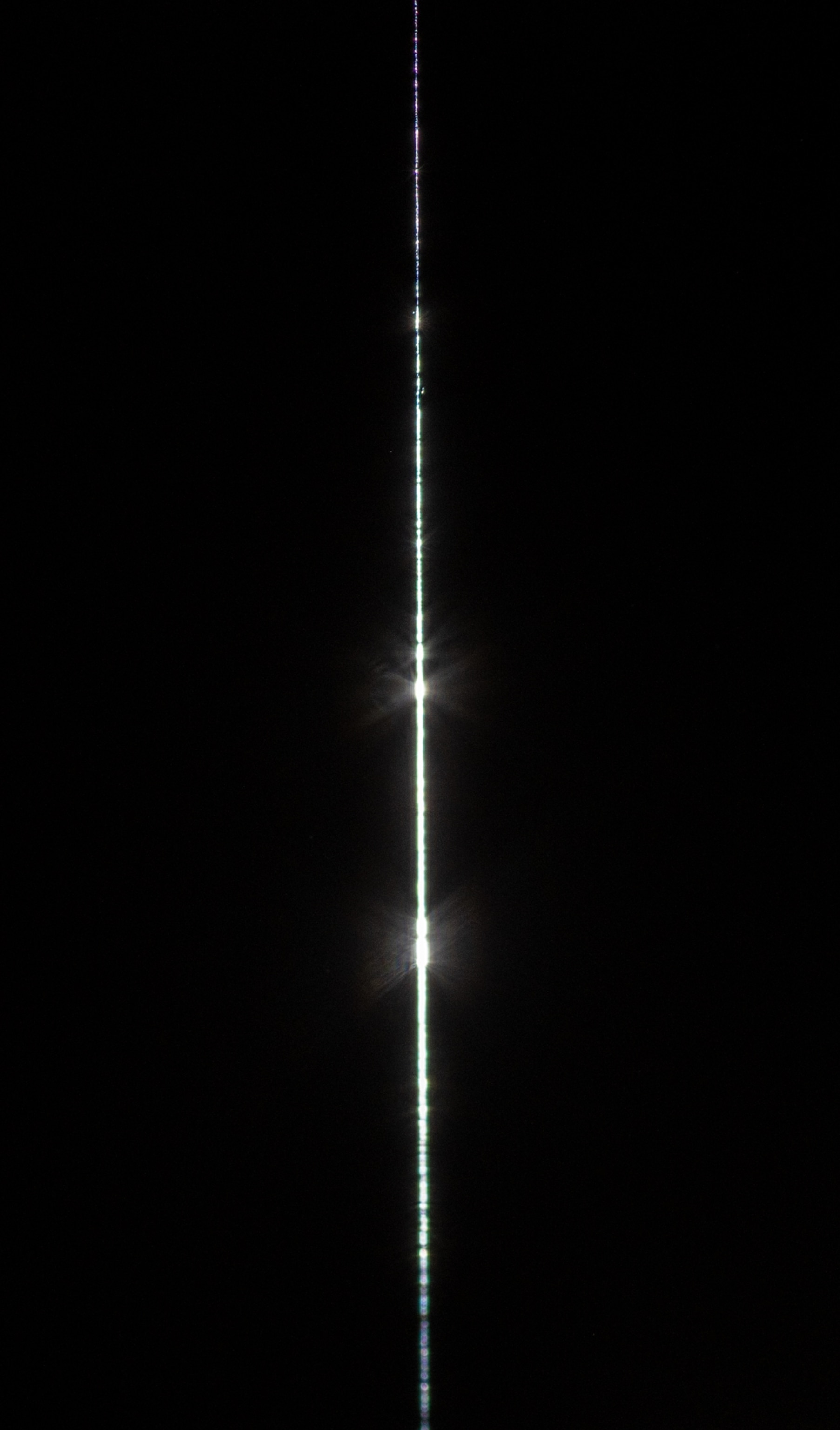

Some 8,000 miles away from Kraig’s Michigan lab, in the steamy silk belt of Vietnam, where there are plenty of mulberry leaves for silkworms to eat and plenty of skilled workers to rear them, Kraig has established commercial-scale farms where these little beasties are weaving supersilk daily. (Many of the company’s worms, including all those in Vietnam, fluoresce green under ultraviolet light and a filter, thanks to the insertion of a jellyfish gene—a way of identifying the modified worms.) It took years to figure out how to keep the lab-grown silkworms from dying under commercial-scale conditions—die-offs that nearly ruined the company—but the kinks have been worked out, says Thompson, and significant quantities of sample fabric will be shipped to major clothing brands for testing in 2026. “After all these years,” he says, “we are finally going to make the shipment.”

For now, Kraig is hoping luxury fashion houses show interest in its stronger-than-silk supersilk, because the clothing industry is the most straightforward—if obvious—path to driving commercial revenue for the first time in the company’s 20 years. In the meantime, it continues trying to engineer silkworms that can spin pure spider silk at scale—all while Kraig’s supersilk-making competition across the globe explores other applications for the material—some simple, some radical.

Spider silk as a supermaterial harnessed by humans has been dogged by both optimistic hype and some material mistakes. Plenty of promising projects have burned up on the launchpad as companies hunt for a real-world application.

In 2015, Japanese start-up Spiber, which uses tanks of genetically engineered microbes to brew silk proteins, designed a parka in partnership with The North Face, only to see it suffer from extreme shrinkage. Spider silk’s tendency to contract as much as 50 percent when wet is an excellent quality for keeping a web taut under the weight of dew, but not for a winter jacket. (A later iteration of Spiber’s silk solved the problem but never made it to mass production.)

Kraig Biocraft’s 2016 contract with the U.S. Army to test its material in bulletproof vests didn’t pan out. Airbus teamed up with Germany’s AMSilk, which also brews protein, to experiment with supersilk-based composite materials for the aerospace industry, but nothing progressed. Supersilk as a world-changing textile has not had much success.

As years of R & D have turned into decades, companies like Spiber, Kraig, and AMSilk have had to find applications that might provide a revenue stream now. And it turns out the most right-now value of spider silk–derived materials might have nothing to do with how we think about fibers.

AMSilk has pivoted toward two applications with a low barrier to entry: dishwashing and laundry detergents. Although the company’s microbe-produced proteins do not yet make superior fabric, they can still link together to form a microscopic and nontoxic biofilm that repels water, keeping dishes and clothes spotless.

“Dishwashing soap is full of chemicals right now,” says Gudrun Vogtentanz, AMSilk’s chief scientific officer. “If you take out the chemicals and add our spider silk protein instead, you get the same performance, but from a sustainability or an environmental point of view, it’s way better.”

A planet-friendly Tide Pod is not going to save the world, but it’s doable today, and it buys an R & D department time to keep working on moon shots—which all the companies involved believe are right around the corner. But those moon shots may be less about the spider silk itself and more about the process of learning to design proteins. “With the advancement of synthetic biology and protein-engineering technologies, it is entirely possible to design artificial proteins that outperform natural spider silk,” says Gong.

That’s Spiber’s approach. Over the past decade, it’s built a library of proprietary protein designs with amino acid sequences that have no analog in nature and allow for product-specific flexibility. “Some designs in this library resemble spider silk more closely, while others are closer to silkworm silk,” says Executive Vice President Kenji Higashi.

Tomorrow it might be a better dish detergent. But the new hope for spider silk lies in revolutionizing human health.

(Chinese brocade is intricate and stunning. Here’s where to find the real deal.)

One of the quirks of materials science is that the inventions often precede the applications. Teflon, aerogel, and graphene were all stumbled upon by researchers seeing what they could make, and then it was up to the world to figure out what to do with it. That may well be the case with supersilk too: We thought we were chasing better bulletproof vests, but the real value lies inside our own bodies.

In the case of spider silk, the quest to unlock the secrets of its strength and flexibility has led to a new understanding of protein structures and how those translate into performance at the microscopic scale. “Beyond fabric, recombinant spider silk proteins can be processed into diverse forms—films, hydrogels, sponges, microcapsules, and nanoparticles,” says Xingmei Qi, who researches spider silk–based therapeutics at Soochow University. “What once seemed nearly impossible is now becoming technically and economically feasible.”

The applications being explored would be revolutionary: Spider silk–influenced gels and biofilms can coat catheters and surgery meshes, reducing infections and blood clots. They can line wound dressings and improve cosmetics. At the nanoscale level, they become Legos, giving gene jockeys the ability to design new molecules one amino acid at a time, forming shapes and functions that go beyond anything available in nature’s pharmacy.

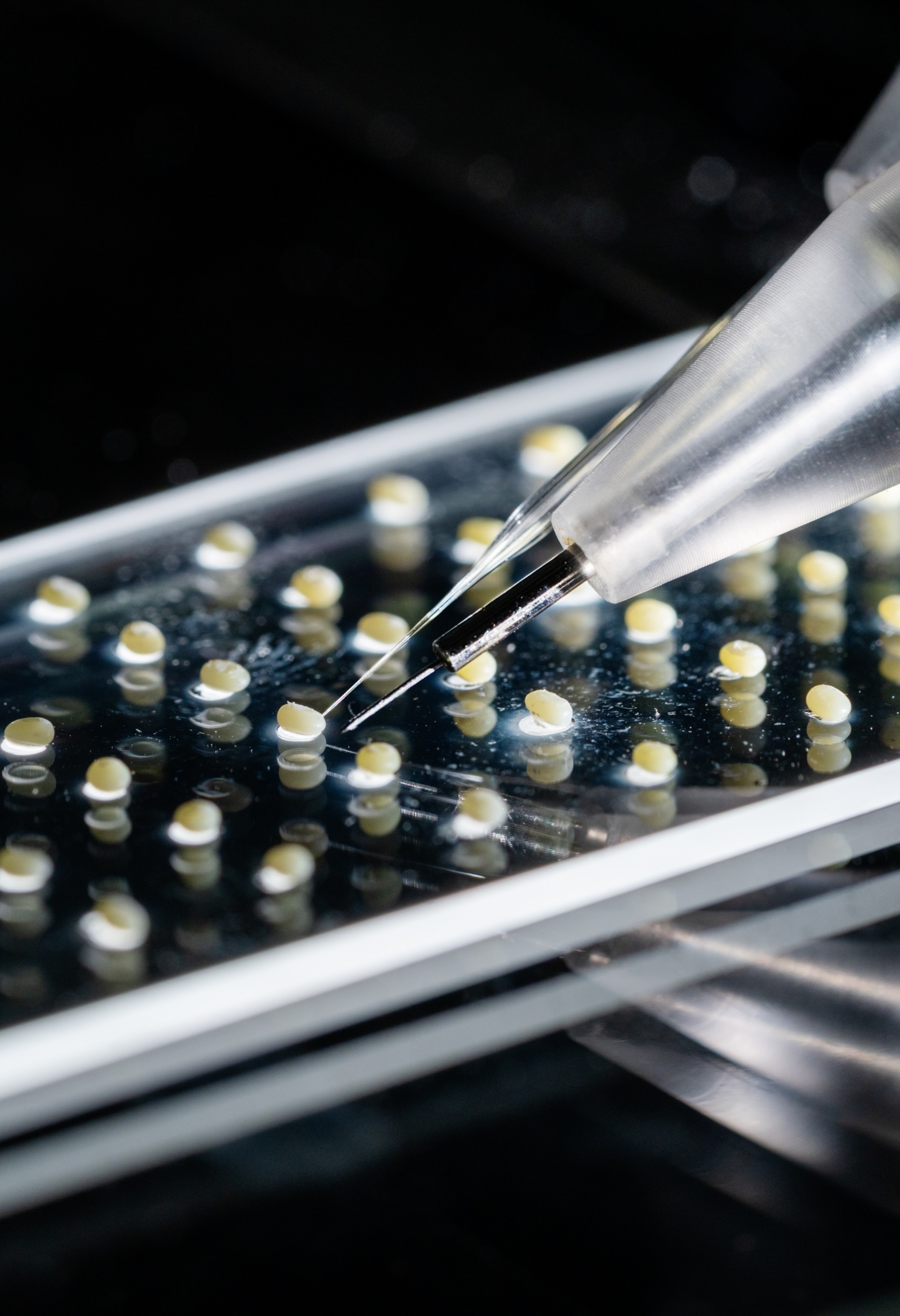

That could revolutionize tissue engineering and drug delivery. The strength and biodegradability of spidroins make them excellent designer scaffolding upon which new ligaments, cartilage, and nerves can grow—and these genetically crafted proteins are extremely well tolerated by the body. “Spidroin nanoparticles already meet most of the critical biomedical requirements,” says Qi. “They are biodegradable, biocompatible, safe, and can be produced under mild, scalable conditions.”

For drug delivery, Qi is currently working on a new generation of vaccines, in which spidroin nanocapsules would carry the delicate immune system–stimulating molecules to their targets and release them at slow, sustained rates. “Ultimately, we hope that these silk-inspired materials will bridge biology and medicine,” says Qi, “turning one of nature’s most remarkable structural proteins into a platform for human health.”

That transformation will not come tomorrow. Navigating the miles of regulations and clinical trials required for the approval of anything in the medical industry takes years. But yet again, supersilk’s hype has found a second wind, and the payoff could be worth the wait. Until then, the hardworking silkworms in Michigan and China and Vietnam will keep munching and weaving, blissfully unaware that they’re pushing science forward with every fiber they spin.