Man Partly Wakes From 15-Year Vegetative State—What It Means

The 35-year-old was able to turn his head and react to visual cues after doctors put a device in his chest that stimulates the vagus nerve.

After a person spends a year in a vegetative state, the condition is considered permanent—there will never be someone “in there” again.

That’s why it’s so surprising French researchers were able to boost the consciousness of a patient who had spent 15 years in a vegetative state following a car accident. Brains aren’t supposed to work that way.

By implanting a device in the patient’s chest, the researchers stimulated the 35-year-old man’s vagus nerve, which runs all the way from the base of the head to the abdomen and is known to be involved in wakefulness and attention.

After a month of daily vagal nerve stimulation, the man’s dramatic improvements defied all expectations, the team reports this week in the journal Current Biology. (Read more about how science is redefining life and death.)

Here’s what we know about the new treatment and what it means for vegetative patients.

What is a vegetative state, exactly?

Someone in a vegetative state can breathe on their own and has periods of wakefulness, but is unaware of their surroundings and can’t communicate or respond to external stimulation. “They don’t have a presence in the world,” explains study leader Angela Sirigu of the Institut des Sciences Cognitives Marc Jeannerod in Lyon, France.

With a coma, by contrast, the person’s eyes are closed; it is possible to recover from a coma and regain full awareness. A person in a coma can also transition to a minimally conscious or a vegetative state or develop locked-in syndrome, where the person is aware but cannot communicate.

It’s hard to know exactly how many people are currently in a vegetative state. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention does not include this information on their website, and a call to them was not immediately answered.

So, did the man suddenly wake up after 15 years?

No. It wasn’t a scene from a daytime soap opera, but his progress was surprising. In medical terms, his condition shifted from a vegetative state to a minimally conscious one. After a month of vagal nerve stimulation, the man was newly able to respond to simple commands, such as slowly turning his head from left to right, Sirigu says.

He was able to stay awake for much longer than before while listening to a therapist read a book. And he responded to perceived threats, opening his eyes wide when someone suddenly approached his face, Sirigu says. People in a vegetative state show no response at all to such invasions of space.

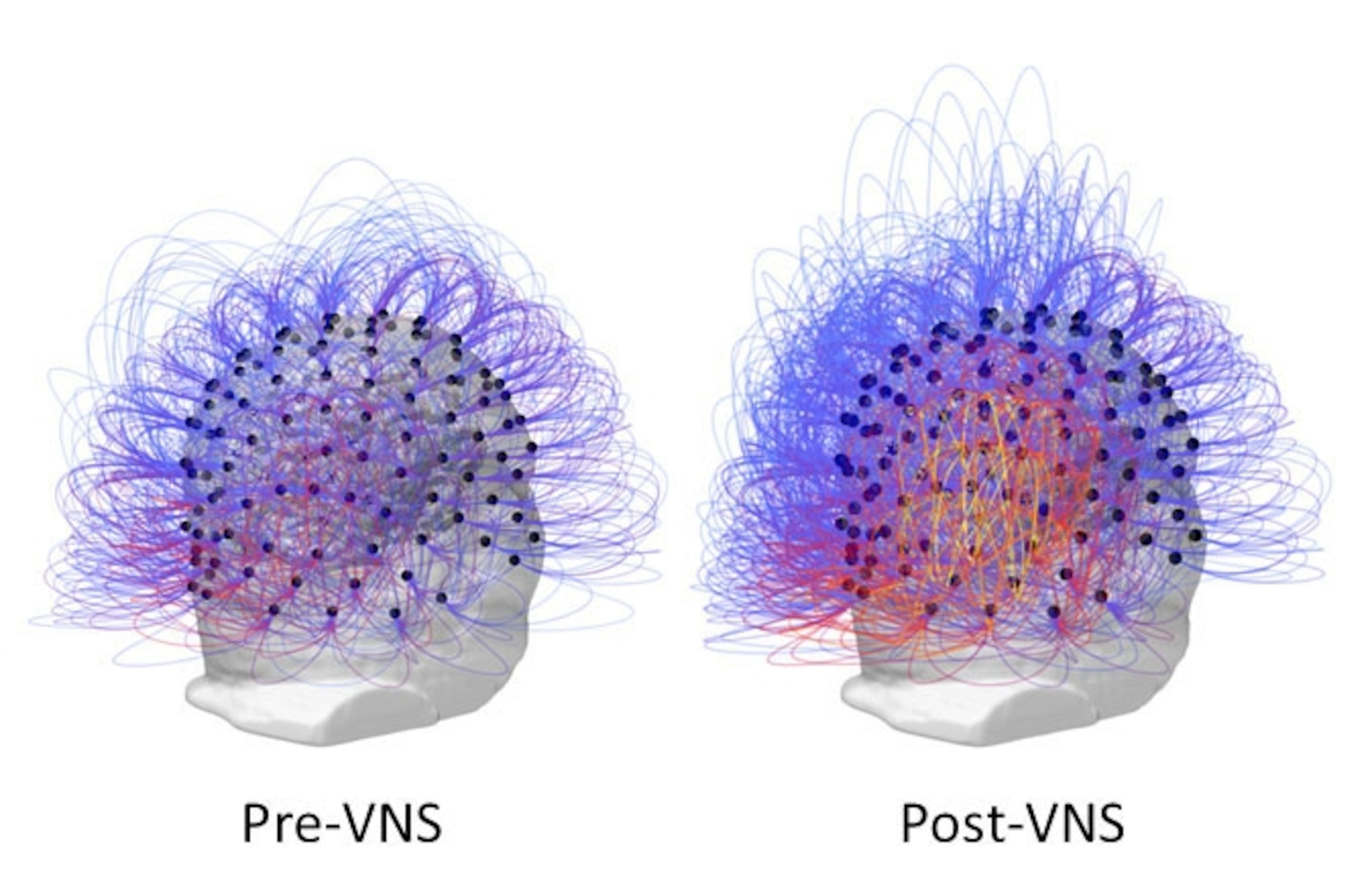

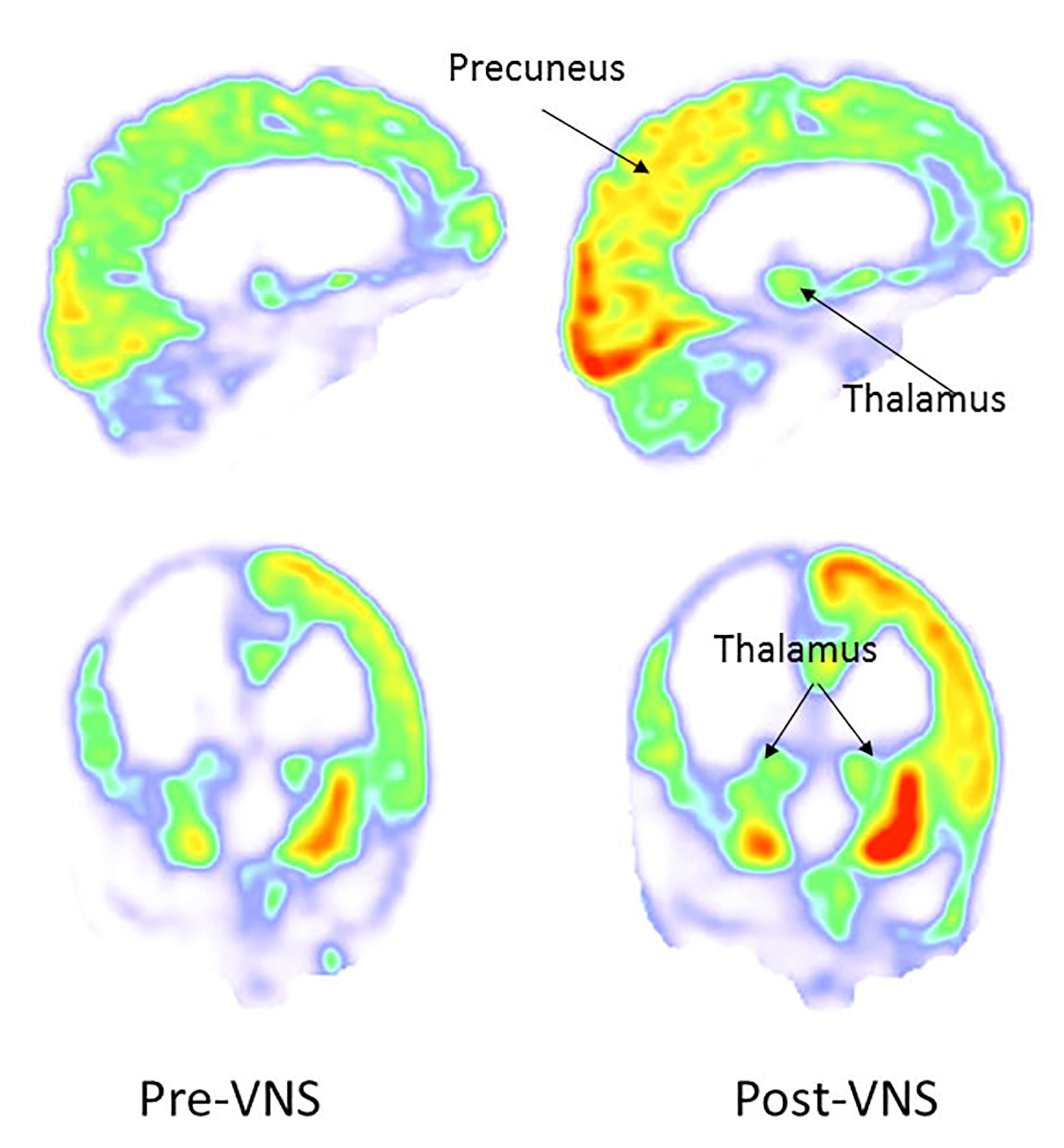

The man’s gains were also detectable in brain images, which showed greater communication among regions of his brain and increased metabolic activity.

Could the man’s recovery have happened by chance?

Probably not. The researchers specifically chose a patient whose condition was longstanding to rule out the possibility of a chance improvement.

How did the researchers think to stimulate the vagus nerve?

Activating this nerve generates signals in the so-called noradrenergic pathway, which is crucial for arousal, alertness, and the fight-or-flight response. Vagal nerve stimulation is already commonly used to treat epilepsy and occasionally to treat depression and neurological disorders. The technique has been tried before in people with recent traumatic brain injuries.

Uzma Samadani, who is using vagal nerve stimulation on patients with moderate traumatic brain injuries, says she is excited by the French results. “I am emphatically in favor of this line of research,” Samadani, an associate professor at the University of Minnesota Department of Neurosurgery, says via email.

“I believe that we do not have full understanding of the mechanisms of impaired consciousness associated with trauma, but that vagus nerve stimulation appears to show promise in this isolated case report.”

What about others with severe brain injuries?

While this case is remarkable, it’s only one example. The researchers will need to confirm their findings in many more patients to understand the full potential of using vagal nerve stimulation to boost consciousness in vegetative patients.

But if the method is shown to work in a broader population, vagal nerve stimulation could give people with limited consciousness at least a bit of free will and the ability to communicate. Vagal nerve stimulation is likely to be more effective when used shortly after a traumatic brain injury, Sirigu adds, which is something she plans to study next.

“The sooner we can stimulate it, the sooner we can interfere with the body functions and restore some kind of physiological equilibrium,” she says.

Is this man truly better off now that he has some awareness of his condition?

That’s hard to say. His family has declined to speak publicly about his progress. But Sirigu is optimistic: "It is always better to understand than not be aware of what others are doing to you or telling you,” she says. “I would prefer to be aware, in any case.”