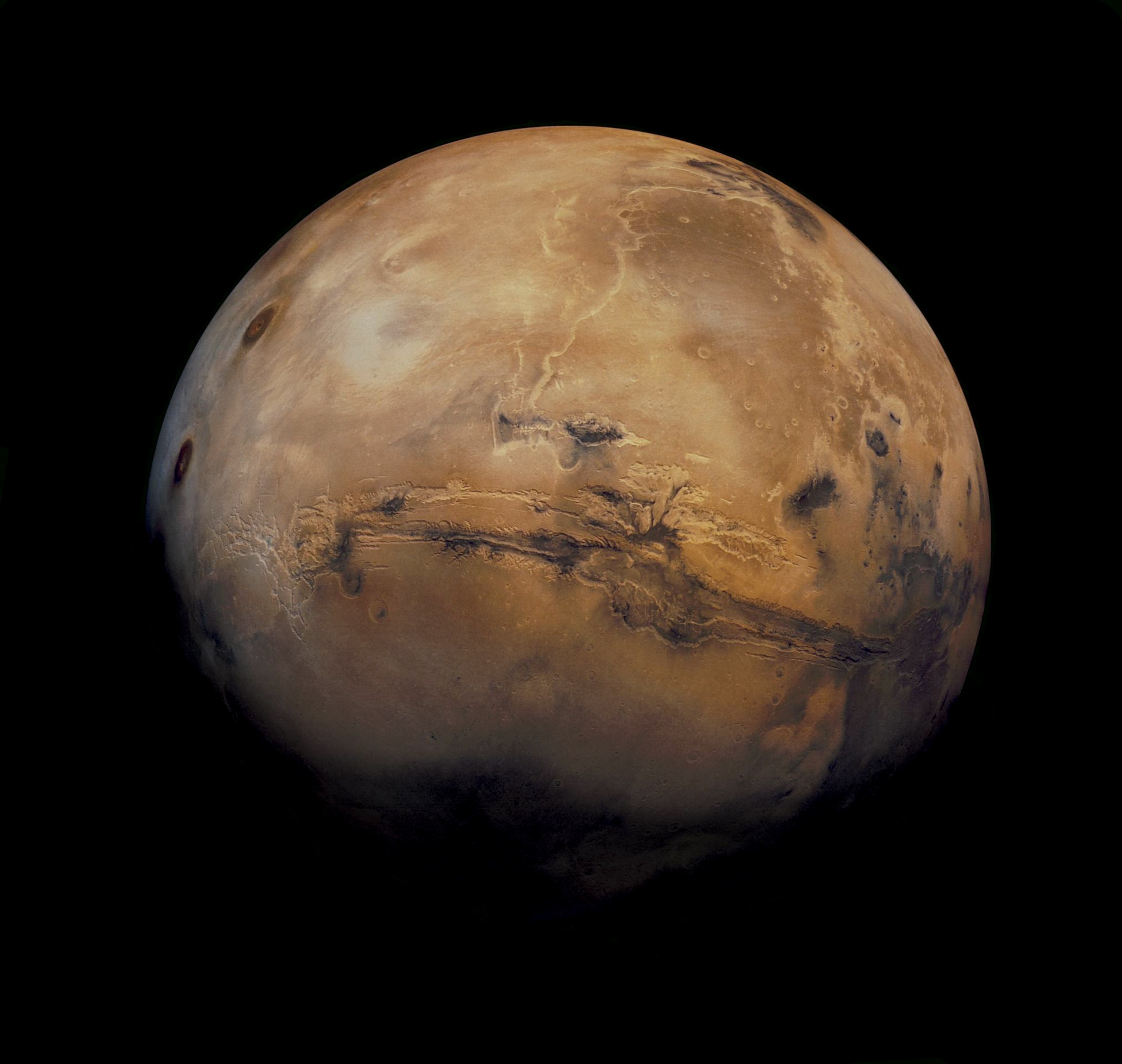

Here’s where NASA is looking for alien life in our solar system

From Viking to Perseverance, scientists have spent decades chasing chemical hints that could point to life beyond Earth.

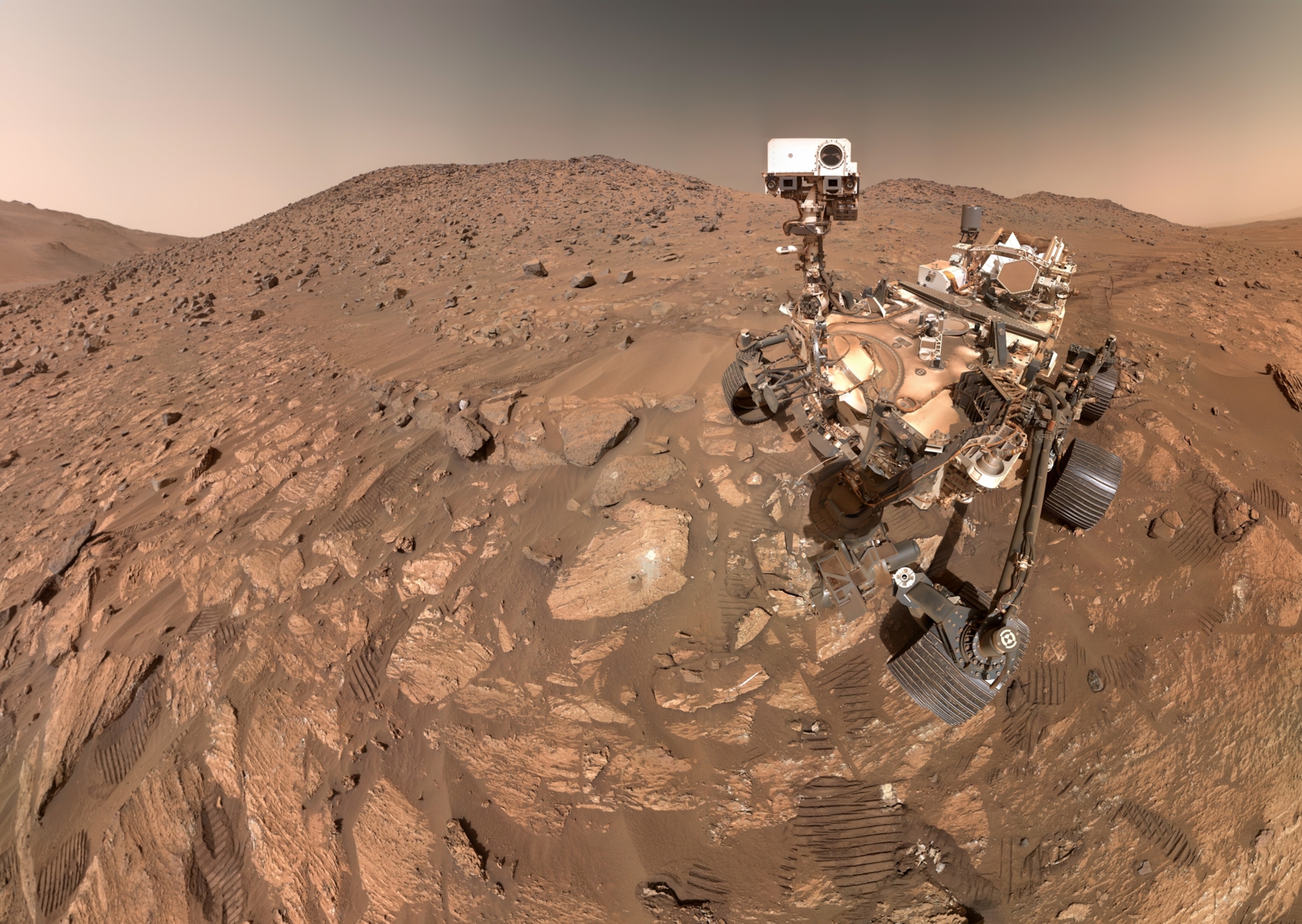

In September, NASA announced the discovery of a possible sign of life, known as a potential biosignature, on Mars. The Perseverance rover, which has been exploring a dried-up lakebed for years, found traces of ancient redox reactions, which can be produced by either life or geological processes.

Though the origin of the reactions remains unclear, the tantalizing discovery represents the latest chapter in the search for biosignatures on alien worlds. For a half-century, scientists have been fascinated and flummoxed by ambiguous compounds and structures on our neighboring planets—and increasingly, exoplanets beyond our solar system. Here’s a primer of the most perplexing finds, and what they mean for our quest to discover life elsewhere in the universe.

What is a potential biosignature?

It’s worth noting that the definition of a potential biosignature is slippery. Geological processes can produce complicated structures, such as crystals and polymers, that make it difficult to separate signs of life from non-living processes.

“If you ask the question—how complicated can non-biological chemistry get?—the answer is biological chemistry, because biological chemistry comes from non-biological chemistry,” says Sean McMahon, an astrobiologist who leads the Planetary Paleobiology Group at the University of Edinburgh.

Indeed, there are structures on Earth that don't clearly fall into biotic or abiotic categories. Frances Westall, emeritus director of research and former director of the Exobiology Group at the Center for Molecular Biophysics in France, says it took her nearly 20 years to confirm the biological origin of Australian fossilized microbes that date back 3.45 billion years. In a study published in September, her team said these microbes, known as chemolithotrophs, could be a common form of alien life that “are notoriously difficult to detect and identify.”

(The is the best evidence yet for ancient life on Mars)

“I had to wait until there was a suitable instrument that could measure these small things and detect the very small amounts of carbon,” Westall says. “It just took ages and ages, but finally, we managed to get the smoking gun results that we really wanted.”

The possibility of abstract or unexpected forms of life, as well as the presence of novel geological processes, could make it hard to even pin down a standard for biosignatures.

“We're looking for a signal above a baseline, and most of the time, we don't know what's in the baseline,” McMahon says. That’s why the search for potential biosignatures has such a nebulous history, on Planet Earth and beyond.

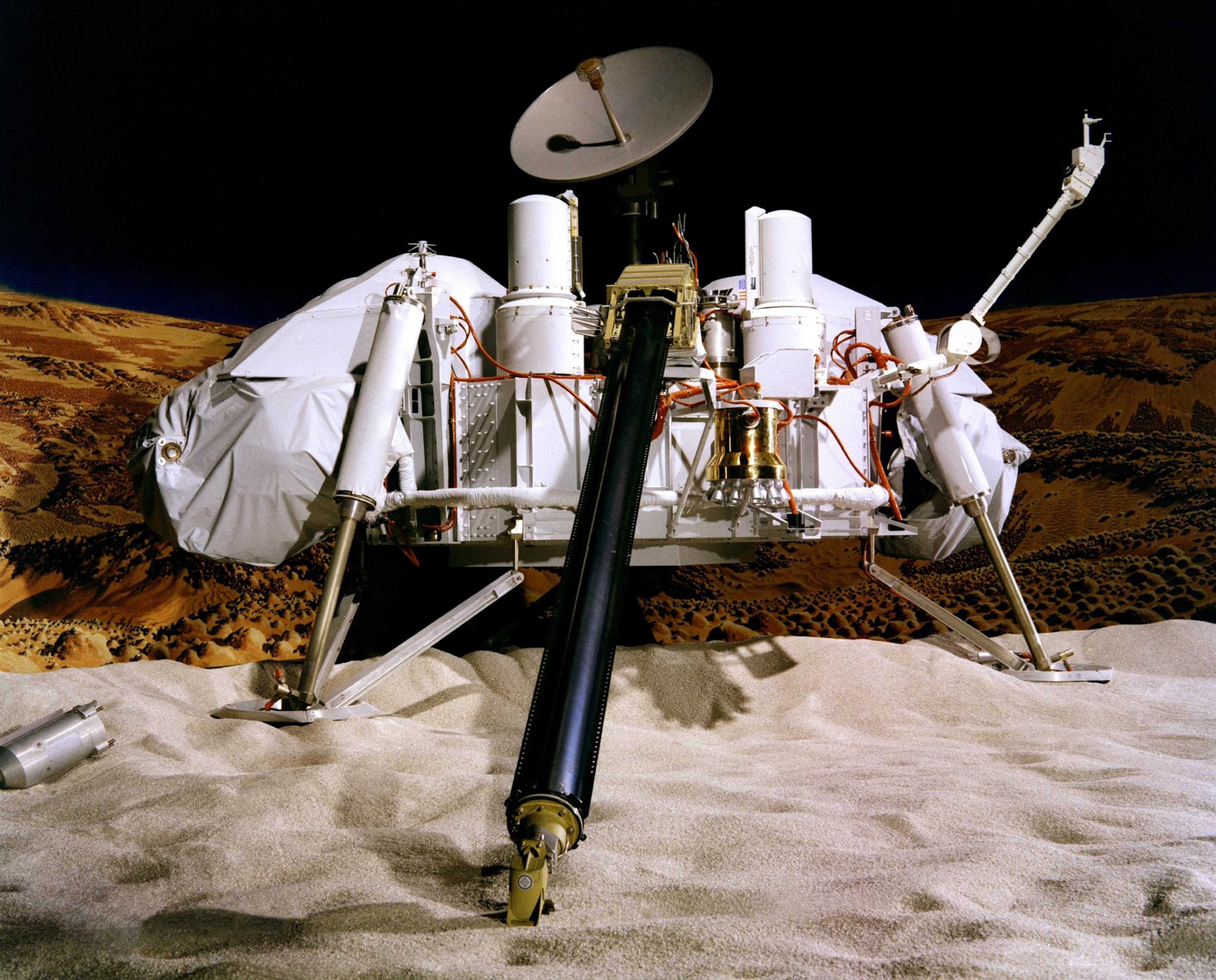

The Viking experiment

NASA’s Viking landers touched down on Mars in the summer of 1976, becoming the first operational robots on its surface. The landers were equipped with a test called the Labeled Release experiment, which mixed Martian samples with water and nutrients to detect biological activity.

The experimental setup involved searching for gasses emitted from the nutrient-enriched sample that would expose metabolic processes from microbes in the Martian soil. Astonishingly, the test detected the very gasses that it had expected to see if life were present in the soil, a result that lined up with earlier tests of Earth soil containing microbes.

But while the outcome was tantalizing, the experiment did not consistently reproduce the same results in subsequent tests. Moreover, as scientists learned more about Martian soil chemistry, it became clear that common abiotic compounds on Mars could have potentially released the mysterious gasses detected by Viking.

The results are now widely considered inconclusive at best, and many possible abiotic explanations have been proposed. Regardless, the whole episode sparked a decades-long controversy over whether the mission really did find aliens.

(Could there really be alien life on this exoplanet? We asked 10 experts.)

“We still don't fully understand what happened, which is a bit shocking when you think about it,” McMahon says. “It was a flawed experiment that was liable to both false positives and false negatives.”

Westall thinks there is likely a non-biological explanation for the Viking mystery, such as the presence of reactive compounds in the Martian soil capable of producing the detected gasses. But she adds that “we could be surprised.”

“It's very difficult to say 100 percent positive or 100 percent negative,” she says. “My feeling is that the analysis was interesting, but we simply do not have sufficient data to say that it was an indication of a trace of extant life.”

A Martian meteorite

Fast-forward two decades: In 1996, President Bill Clinton announced the “possible discovery of life on Mars” after scientists identified strange structures in a Martian meteorite that landed in Antarctica, known as called Allan Hills 84001. Though researchers initially speculated that the structures might be “fossil remains of a past Martian biota,” there is now widespread consensus that they can be explained by abiotic geochemistry.

The story of the Allan Hills meteorite has often been viewed as a cautionary tale of jumping the gun, but it also helped to stimulate public interest and academic investment in the search for life in other words.

“Despite the fact that their interpretations were wrong, the study really pushed the field of astrobiology,” Westall says. “We know a lot more now, 30 years after they published that paper.”

(How many alien civilizations might be out there?)

Atmospheric biosignatures

Beyond searching for signs of life on the surfaces of other worlds, scientists are increasingly gazing into the skies of distant planets to look for atmospheric chemistry that might hint at biological activity.

In 2021, a team reported a detection of phosphine, a compound that has both biotic and abiotic origins, in the atmosphere of Venus. Earlier this year, another team reported a potential atmospheric biosignature on the exoplanet K2-18b, located some 124 light years from Earth. Both results generated spirited pushback and inspired research into non-biological explanations, which will likely be a common theme in the coming years as we peer deeper into extraterrestrial skies.

“We've barely started to scratch the surface of the chemistry of exoplanet atmospheres,” McMahon says. “The way that we're going to find life begins with making an observation that we can't explain, and then the real work is figuring out all the possible explanations and doing the scientific detective work.”

To that end, Perseverance’s new discovery of redox reactions is thrilling, but it is only the start of a new story, not the conclusion. The plan is ultimately to send another spacecraft to Mars to pick up Perseverance’s’ samples and bring them back to Earth where they can be thoroughly examined. This effort could potentially reveal whether Perseverance has already discovered alien life, though the sample-return effort is imperiled by the current administration’s proposed cuts to NASA.

Perhaps one day, we will be able to clearly identify a true alien biosignature, finally solving the great riddle of whether we are alone in the universe. But we will likely need a whole lot of patience and dedication to reach that milestone.

“It would be terribly, terribly exciting,” says Westall of the possible discovery of alien life. “But I think it will probably be like looking for a needle in a haystack.”