Researchers recover a woolly rhino genome from inside a frozen wolf's stomach

The work marks the first time an Ice Age animal’s complete genome has been recovered from tissue preserved inside another ancient animal.

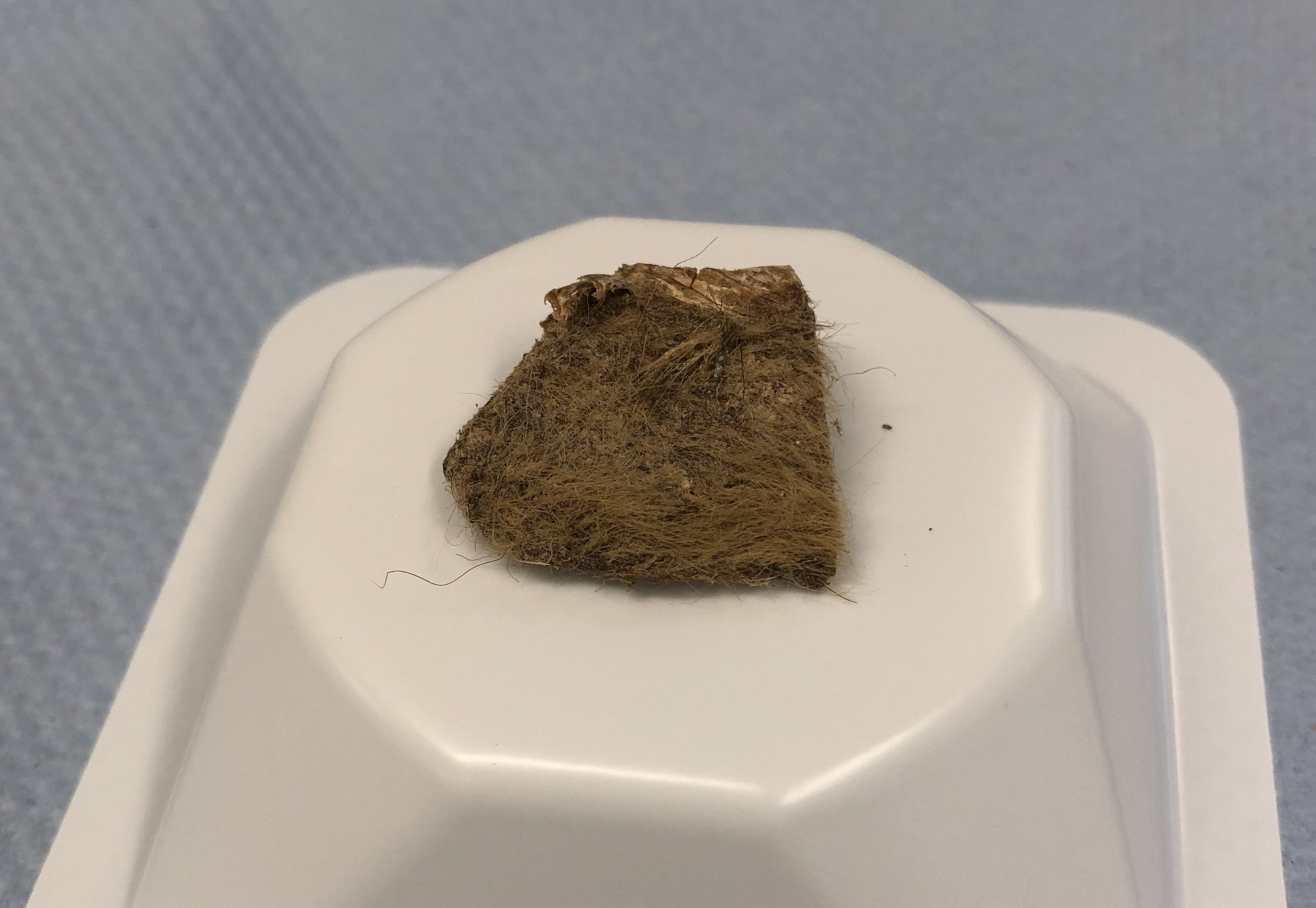

In 2011, mammoth ivory hunters in northeastern Siberia discovered a mummified wolf puppy that had lain frozen for 14,400 years. An autopsy of the permafrost-preserved pup revealed another surprise: its gut contained chunks of grayish meat covered with strands of golden hair.

“The tissue was so intact, it looked like the wolf had just swallowed it before it died,” says Camilo Chacón-Duque, an evolutionary geneticist who previously worked at the Centre for Palaeogenetics in Stockholm and is now at Uppsala University in Sweden.

Ancient DNA retrieved from the wolf cub’s final meal revealed the tissue belonged to a woolly rhinoceros. Chacón-Duque and his team used the devoured morsel to reconstruct the woolly rhino’s entire genome—the first time scientists have sequenced an Ice Age animal’s complete genome from the contents of another animal’s stomach. They published their findings on Wednesday in the journal Genome Biology and Evolution.

The woolly rhino genome provides insights into the species’ population right before the end of the last Ice Age. The findings suggest Siberia’s woolly rhino population was still stable a few hundred years before the shaggy species went extinct. It adds further evidence to the theory that woolly rhinos experienced a rapid population collapse around 14,000 years ago as the climate changed.

Frozen wolf puppies

The mummified wolf puppy was discovered near the Siberian village of Tumat. Together with its sister, which was unearthed in 2015, they are known as the “Tumat puppies.” The siblings were buried in ice shortly after death, likely by a collapsed den or landslide. They were preserved in exquisite detail: both are still covered in parchment-like skin with large patches of dark brown fur. One still bares its teeth, frozen in a permanent snarl.

(World’s longest woolly rhino horn discovered in melting Siberian permafrost)

The rapid burial also captured the puppies' last suppers. Their guts contained a varied diet including bird feathers, bits of plant material, and even parts of a dung beetle. But their most substantial sustenance, it seems, came from scraps of woolly rhino meat.

Siberia was the last stronghold for these gargantuan grazers, which sported the largest horns found of any animal so far. The rhino that ended up as puppy chow is one of the most recent individuals in the species’ fossil record, which, by some estimates, ends around 14,000 years ago. That suggests this individual was among the last generations of woolly rhinos to roam the Earth.

Reconstructing a woolly rhino's genome

Because the rhino tissue showed little evidence of digestion, Chacón-Duque and his colleagues thought it might have retained genetic insights into the species’ extinction. However, the animal’s ancient DNA was poorly preserved.

“We knew it was going to be difficult to piece together a complete genome, but the specimen was too exciting not to try,” says Sólveig Guðjónsdóttir, a graduate student at Stockholm University and a co-author of the paper.

The researchers compared genetic sequences in the tissue to the genome of a Sumatran rhino, the woolly rhino’s closest living relative. They also analyzed gray wolf DNA, which confirmed that the genetic traces in the tissue mostly represented the rhino rather than the wolf cub that ate it, according to Guðjónsdóttir.

(57,000-year-old wolf puppy found frozen in Yukon permafrost)

Laura Epp, an environmental geneticist at the University of Konstanz in Germany, who was not involved with the paper, says she was not surprised that digestive tracts are “good archives” for paleogenetics. The new paper, she says, further shows the types of interesting samples that can preserve ancient genetic information. In 2023, for example, Epp and her team recovered woolly rhino genetics from the petrified poop of cave hyenas.

“We are only just starting to understand how large the potential is” of these types of ancient DNA sources, she says.

An abrupt extinction

To put the woolly rhino’s genetics in context, the team compared it with genomes from two older rhino specimens that lived in Siberia between 49,000 and 18,000 years ago. The genomes revealed that the woolly rhino population there was stable and showed little evidence of inbreeding in the thousands of years leading up to extinction. This was unexpected, says Chacón-Duque, because the populations of many species shrink before extinction, thereby reducing genetic diversity.

The timing of the woolly rhinos’ disappearance coincides with a period of dramatic warming that punctuated the last Ice Age. However, other scientists propose that human hunting also played a role in the woolly rhino’s disappearance during this climatic warm snap.

“Our species probably also did better during these warm intervals at the end of the last Ice Age,” says Advait Jukar, a vertebrate paleontologist at the Florida Museum of Natural History who was not involved in the new research. Referring to research from 2024, he says it's likely ancient humans “pushed these rhinos into parts of their range that were sub-optimal, making them more vulnerable to climate or human hunting.”

While scientists still debate the exact cause of the woolly rhino's demise, the species was vulnerable due to its size, Chacón-Duque says. The rhinos’ population, although genetically diverse, was still much smaller than when the species trudged across Eurasia’s frigid mammoth steppe for hundreds of thousands of years earlier in the Pleistocene, he says. This likely also made the rhinos vulnerable to disaster.

(World’s oldest RNA found in 40,000-year-old woolly mammoth)

In 2024, Chacón-Duque and his colleagues investigated the genetics of another Ice Age titan, the last woolly mammoths on Wrangel Island. They discovered that the isolated population, while inbred, survived for about 6,000 years before it was abruptly wiped out by a tundra fire or a disease outbreak.

“It could be a similar story with the woolly rhinoceros,” Chacón-Duque says. “The rhinos seem to be stable, and then something sudden happens, and they just disappear.”

Additional genetic clues thawing from the Siberian permafrost may offer more clues into what doomed the woolly rhino. And as the latest finding suggests, insights into extinction can be found anywhere, including inside a frozen wolf puppy’s stomach.