Beat the crowds at these abandoned U.S. national parks

These 7 spots might have lost their national status—but you can still explore their rich history and natural beauty.

The national parks system sees about as many visitors each year as there are citizens in the U.S., which can mean long lines, full shuttles, and cramped parking lots. But there’s a savvy secret for escaping into nature while avoiding the typical national park crowds—try visiting former national parks.

Over the past century, dozens of national parks and monuments have been redesignated, reduced, or simply erased (typically for lack of funding). The challenge to parklands is real: 2017 saw the greatest reduction of parks and monuments in U.S. history, CNN reports. Although losing protected status places some areas in precarious positions, it doesn’t necessarily mean people can’t still visit them.

While their names may have changed, these destinations’ history remains. Here are seven former national parks or monuments ready to be explored.

Chickasaw National Recreation Area, Oklahoma

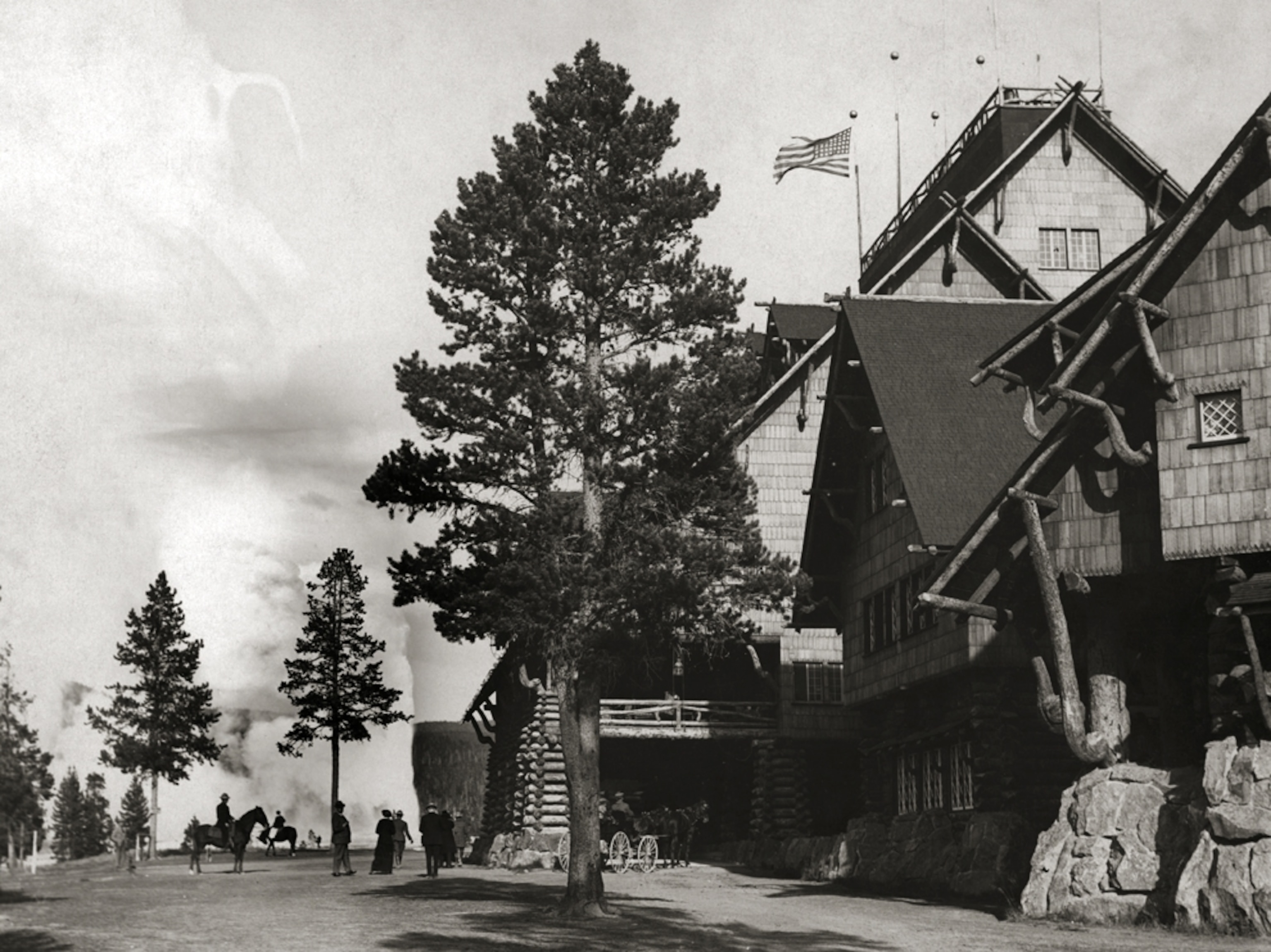

A century ago, Platt National Park (1906–1976) was more popular than Yellowstone. Its 33 cold-water, “healing” springs and quiet hardwood forests attracted a million visitors annually, but America’s seventh national park was too understated to last. When forced to choose between parks, congress funneled funds into Yellowstone and removed Platt’s national park designation.

Expanded and redesignated as Chickasaw National Recreation Area in 1976, the former national park still sees 1.4 million annual visitors. Swim in Travertine Creek’s stone pools (designed by the Civilian Conservation Corps), hike between the five remaining springs, and watch the sun set over Veterans Lake. Stay in the cabins surrounding Lake of the Arbuckles—or Sulphur, Oklahoma, the area’s turn-of-the-century frontier town.

Wheeler Geologic Area, Colorado

Bryce Canyon’s smaller cousin sits in southern Colorado, largely forgotten. A hundred years ago, Wheeler National Monument (1933–1950) was second only to Pike’s Peak in the ranks of the state’s busiest attractions. Then Pike’s Peak got roads—and Wheeler didn’t. The muddy trek up to 12,000 feet was barely fit for horses, and a newly car-loving society wasn’t having it.

The redesignated Wheeler Geologic Area, part of the Rio Grande National Forest, hasn’t changed much. The road still requires a 4x4, but deep, muddy ruts will make you want to hoof it. It’s a strenuous 14-mile round-trip hike, but if you can make it—staying overnight at one of the campsites near the end of Wheeler Road—it’ll be just you, volcanic tuff, spires, and minarets reaching for the clouds.

Mackinac Island State Park, Michigan

The next time you’re hopping between fudge shops on car-free Mackinac Island, gazing out from the Grand Hotel’s front porch, or photographing the iconic Arch Rock, remember that you’re in the nation’s second national park (1875–1895). The War Department—via Fort Mackinac—ran the entire island, but when the fort was abandoned, so was Mackinac’s future as federal land.

Mackinac Island State Park, the first “state park” in the country, is a remnant of this forgotten story. It’s best to explore Mackinac before the first ferry arrives—around 8 a.m.—to experience a crowd-free island more reminiscent of its quieter past.

Sullys Hill National Game Preserve, North Dakota

Even Teddy Roosevelt’s soft spot for North Dakota hardly explains Sullys Hill. Microscopic by national park standards, this 1.25-square-mile patch of steep hills, lakeside wetlands, forests, and prairie was remarkably underdeveloped and underutilized in 1904. And it stayed that way: Five years into its lofty designation (1904–1931), it still had no roads. Annual visitors numbered in the hundreds. And then the Great Depression hit. With no resources to speak of, the park was redesignated a national game preserve.

Today, Sullys Hill—near Fort Trotten—bustles. Elk, bison, prairie dogs, and 70,000 annual visitors keep Roosevelt’s vision alive. Climb the 193-step hill Lt. Col. Alfred Sully forgot to show up to battle for, spend a sunny day exploring the four-mile wildlife loop, and wander the elm-and-basswood forest lining Sweetwater Lake.

Fort McHenry National Monument, Maryland

You’ve likely heard the story: After seeing an American flag flying victoriously over Baltimore Harbor, Francis Scott Key penned a little ditty known as “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Those “broad stripes and bright stars” flew over Fort McHenry, and if national parks were about enshrining moments, its previous designation might have stuck. But after 14 years, Fort McHenry National Park (1925–1939) was redesignated a national monument and historic shrine.

The fort is accessible via I-95 or by water taxi from Baltimore’s Inner Harbor. While on these historic grounds, check out the Visitor and Education Center, take a self-guided tour through the star-shaped fort, and catch a ranger talk or flag change.

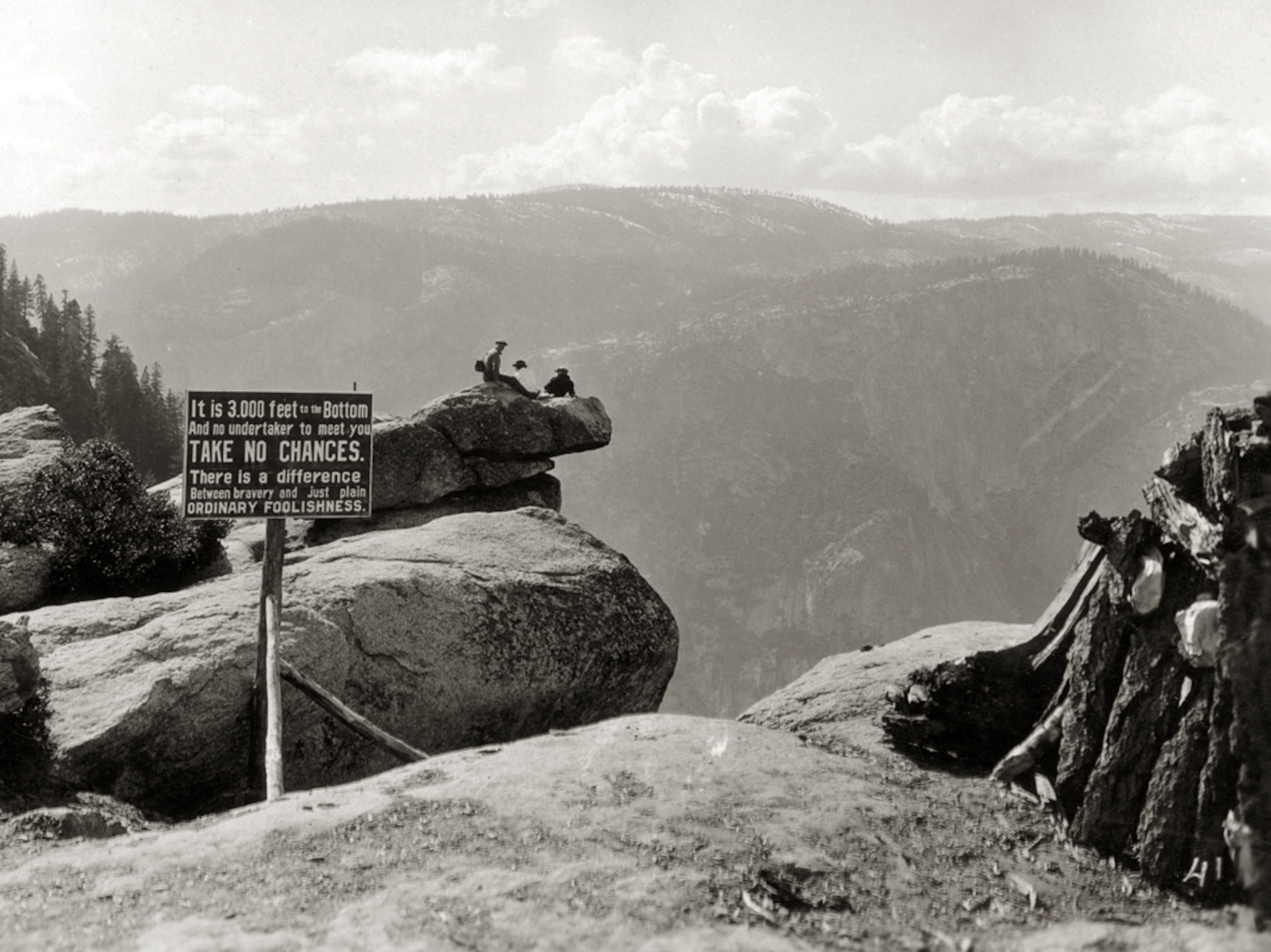

Papago Park, Arizona

Papago Saguaro proves that we, the public, are nature’s most mercurial stewards. Though designated a national monument in 1914 for its unusual rock formations, petroglyphs, and saguaro population, it wasn’t long before locals vandalized the rocks and petroglyphs and stole the saguaro—for lawn decorations.

By 1930, the state asked for the land back. Now, municipal Papago Park is a fraction of its former self. Hole-in-the-Rock, one of the monument’s first attractions, is still easily accessible via a quarter-mile trail, and the Phoenix Zoo and Desert Botanical Garden are both on former national monument grounds.

Lewis & Clark Caverns State Park, Montana

In the early 1900s, the Lewis & Clark National Monument (1911–1937) was only accessible via a 45-minute climb up a 2,000-foot staircase—the original entrance sat at 1,400 feet above the Jefferson River. At the end, visitors were greeted by unlit caverns, a maze of tortuous passages, and no staff. The state rightly believed they could do better, successfully pushing the federal government to turn over the land that became Lewis & Clark Caverns State Park, Montana’s first.

Today’s park spans 3,000 acres and offers 10 miles of trails, a fantastic visitor center, and the 4.5-mile-long cave—packed with delicate limestone formations—most certainly has lights. Guided tours run May through September, with festive candlelight tours held during the holidays.