Can Appalachia’s world-class rafting help coal towns thrive?

The benefits of a surging adventure industry are real, but challenges remain.

Appalachia has long struggled to throw off its stereotypical image of impoverished miners and moonshiners—and its recent outdoor recreation boom might be helping.

The sprawling region, which stretches along the Appalachian Mountains from northern Mississippi to southern New York, gained notoriety in the 1960s as the epicenter of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s “War on Poverty.” But that doesn’t tell the whole story of an area that today is home to more than 25 million people—and which welcomes millions of visitors every year, drawn to the natural assets helping some communities bounce back from the economic brink.

Releasing the river

One such community is Fayetteville, West Virginia, bracketed by the New and Gauley Rivers, which plunge through billion-year-old gorges. Here, each morning for 22 days every fall, the U.S. Corps of Army Engineers opens the gates of the Summerville Dam, unleashing torrents of water that attract thousands of rafters from around the world to “Gauley Season.”

“My dad was a coal miner,” explains guide Mike Sharp, as our raft rapidly approaches a section of white water on the New River. “As a kid, I spent two-thirds of my summer right here on this river, with my brothers.” Above the growing roar of gushing water, he warns us to get braced in.

Sharp is one of about 600 people employed by outfitter and resort Adventures on the Gorge during the fall high season. His job is to guide thrill-seekers through West Virginia’s wild waters. His backstory, which reflects a generational shift away from extractive industry work toward jobs in outdoor recreation, isn’t uncommon here.

Fayetteville (population: 2,700) sits on some of the country’s highest-grade coal; mining formed the region’s economic backbone for decades. Since 2008, however, coal production in West Virginia is thought to have fallen by 40 percent. The number of coal miners in Fayette County has halved in the last decade to around 600.

Recreation, however, is on an upswing. Although the number of people taking commercial rafting trips has fallen nationwide since the 1990s—including in West Virginia—industry experts estimate that in 2019 the state hosted around 103,000 trips, channeling some $30 million into the economy. Independent kayakers and rafters are believed to bring West Virginia another $5 to $10 million a year. Advocacy group America Outdoors identifies the New River, which flows just west of Fayetteville, as one of the most popular rafting rivers in the U.S.

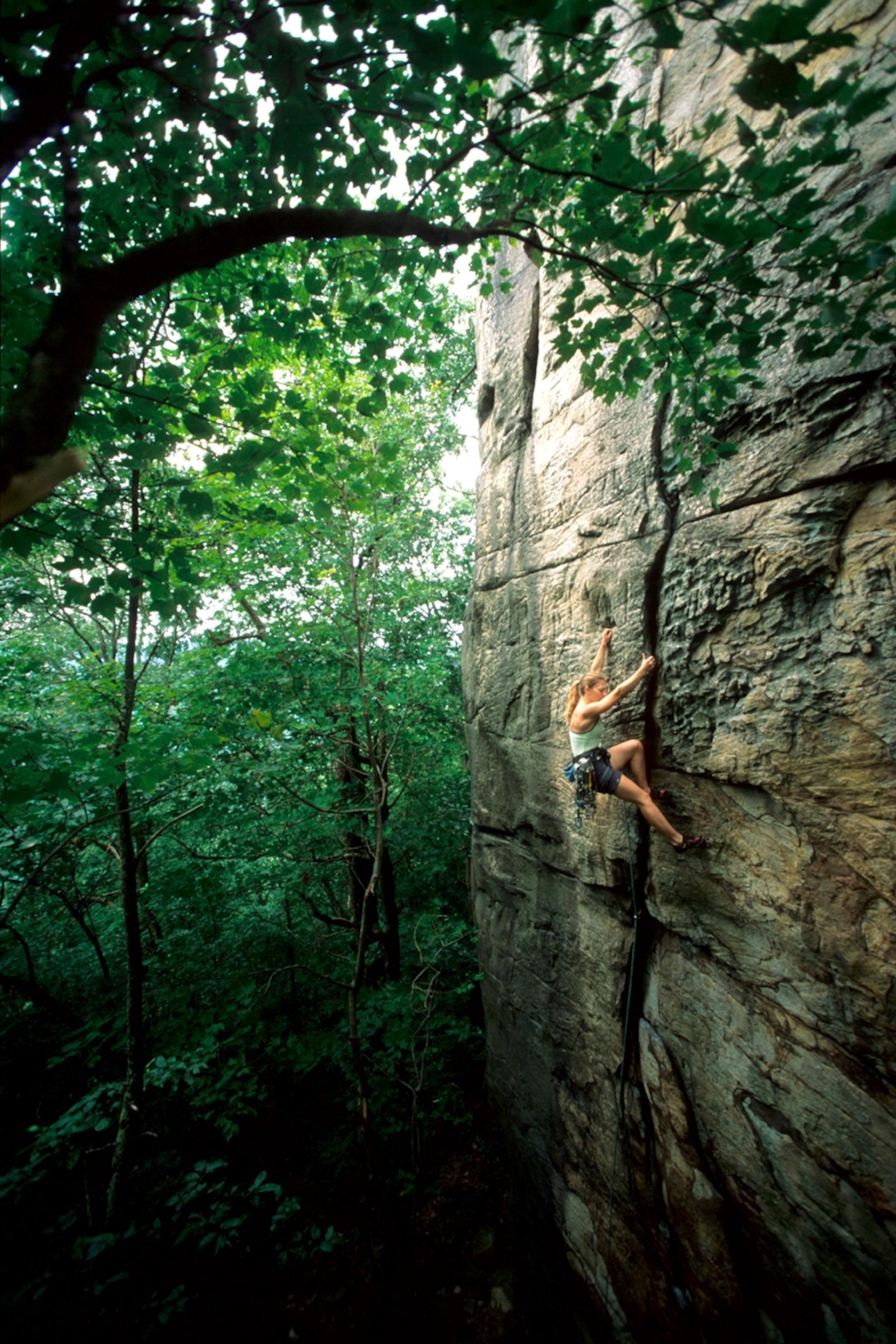

Fayetteville’s outdoor recreation companies have broadened their offerings to include seasonal camping and rock climbing, as well as year-round zip lining on vast, wooded campuses. Rock climbing at nearby Summerville Lake and other local spots has exploded in recent years, adding $12 million a year to the economies of Fayette County and its neighbors, Nicholas and Raleigh Counties. And every October, some 80,000 people cram onto the New River Gorge Bridge to watch BASE jumpers dive into an 876-foot deep chasm. These events and industries have sparked new businesses, from gourmet sandwich shops and craft breweries to live music venues.

Uphill struggles

But is it all free-flowing IPAs and s’mores over the campfire? Not exactly.

Fishing and hunting still make up the largest portion of outdoor recreation revenue in West Virginia. Sporting groups oppose the potential loss of 4,800 hunting acres, should the New River Gorge National River be designated a national park and preserve, following a 2019 bill introduced to the U.S. Senate by West Virginia Senators Shelley Moore Capito and Joe Manchin.

On the other hand, several rafting outfitters think official support of outdoor adventure tourism is still lagging: They point to the lack of state-level investment in marketing newer recreation offerings. “All of West Virginia tourism has a lack of awareness,” says Rick Johnson, who has led rafting trips with River Expeditions for 24 years.

Education is another barrier to growth. According to the nonprofit Greatschools.org, 80 percent of Fayette County’s schools rank below the state average, making it harder to recruit and retain good workers, especially those with families.

“When our oldest child hit school age, my wife and I struggled to justify staying,” says Jay Young, a North Carolina native who has worked with the Adventures on the Gorge for 13 years after moving from Charlotte, North Carolina.

Young’s family found a small, nonprofit, private school that opened in 2009. “We went from thinking we had to leave to educate our children the way we wanted to thinking we should never leave,” Young says—though he doesn’t anticipate additional private schools opening in the area anytime soon.

The Appalachian divide

Some Appalachian towns, including Asheville, North Carolina, and Gatlinburg, Tennessee, are well-established outdoor meccas with large marketing budgets. That’s partially due to their prime locations on either side of Great Smokey Mountains National Park, America’s most-visited. But smaller communities farther from major population centers—like Pikeville, in eastern Kentucky; St. Paul, Virginia; and Fayetteville—face a struggle.

“Part of it is just getting the word out,” says Shannon Blevins, vice-chancellor at the office of economic development and strategic initiatives at the University of Virginia, Wise. “There are some anchor outdoor recreation opportunities, [but] one single town might not have enough for people to come and stay for a week.”

Blevins warns that Appalachian communities shouldn’t go all in for recreation at the expense of developing other industries. “Tourism isn’t recession-proof,” she says. And overinvesting carries its own risks. Case in point: Athens, Ohio’s plans for an 88-mile, $12 million bike park, which have raised concerns that the small university town may have bitten off more than it can financially chew.

But for now, Fayetteville’s future looks bright. The town’s profile is rising, with 2021’s National Scouts Jamboree set to bring 40,000 participants to Fayette County. Although challenges remain, the growing variety of outdoor recreation opportunities might be what helps bring economic stability back to the area. If that happens, visitors will be able to see for themselves what Appalachia is really like today.

Getting there

Where to eat: Find one of the area’s tastiest menus at Smokey’s Cast Iron Grill (open daily May to October; off-season, Sundays only) at the Adventures on the Gorge resort in Lansing. In Fayetteville, drop by Southside Junction Tap House for a craft beer and a relaxed vibe.

Where to stay: From campsites to high-end cabins, Adventures on the Gorge covers a lot of ground. In Fayetteville, the Historic Morris Harvey House Bed & Breakfast recalls old-time Appalachia.

What to do: Fayetteville has zip lining, overnight fishing trips, and a spectacular, thousand-yard bridge walk. Nuttallburg Mine—an abandoned 19th-century facility of conveyors, coke ovens, and disused rail track—lies alongside the Headhouse hiking trail just west of town.

But it’s Gauley Season (September and October) that sets the area apart, with good reason. Over a 12-mile stretch, the Gauley River drops more than 330 feet, blasting through five sets of class V rapids.