Breaking bread: the smoky taste of Nashville, Tennessee

Pitmaster Pat Martin spends his working day barbecuing and his free time grilling — two very different things if you’re in the American South, where cooking is as much about the journey as the destination.

Pat Martin drives like he lives: at about 100mph.

Ironic, then, that he’s a local hero in Nashville for his West Tennessee whole hog barbecue: among the lowest and slowest of techniques, involving a pitmaster patiently sweating it out next to smouldering hickory chips for 24 hours. Some chefs might balk at devoting this much time to a single ingredient. But if there’s one thing I learn from Pat, it’s that Southern cooking is as much about the journey as it is the destination — process and ritual being every bit as important as what ends up on the plate. Even a guy like him, barrelling down life’s fast lane, slows down to make a meal.

He’s a textbook alpha — broad-chested, salt-and-pepper beard, trucker’s cap — but Pat isn’t beyond getting sentimental about food. “When I was little, we’d load up a van with coolers and drive down to the Gulf Coast to meet the shrimp boats,” he bellows over the competing roars of radio and engine, simultaneously fielding phone calls and wrestling the gear stick. “It was a five-, six-hour drive, just to get shrimp. But that was the fun of it — riding down with my dad in a van.”

Little wonder Pat has built a culinary empire, with 10 Martin’s Bar-B-Que Joint restaurants to his name so far, even taking the Tennessee whole hog over state lines to South Carolina, Alabama and Kentucky. But he’s also a keen home cook, hosting backyard cookouts for fellow Nashville chefs. Lately these gatherings have tailed off, as the city’s breakneck growth keeps everyone busy — Nashville is adding residents at twice the national average pace, and business is booming. Tonight, though, I’ll have the honour of attending a now all-too-rare get-together, along with a few core members of the Martin’s Bar-B-Que Joint family.

When catering at home, Pat prefers a quicker method to the one that made his name. But he does have one rule: “If we’re cooking it, we’re grilling it.” That means most of what we’ll be eating will have been touched by smoke, a signature flavour of Southern cuisine.

“You can’t replace the taste of that,” Pat explains. “Smoke, char — it’s very unique.” Getting out the grill to create those flavours is a real event in Southern culture: “Growing up, we grilled every Saturday, methodically building fires from scratch,” he says. “My dad first asked me to start a fire when I was 11 or 12. It was a rite of passage.”

If you were under the impression that the terms ‘barbecuing’ and ‘grilling’ are interchangeable, this would mark you as a hopeless amateur in the South. Nowhere else will you find such fierce distinction between the techniques, probably because they’re so integral to the region’s traditions. Grilling is done quickly, over direct heat at high temperatures, whereas barbecue requires indirect heat — coals are shovelled to one area of the cooker, the meat to another — hence the phrase ‘low and slow’. Barbecue is actually rooted outside the United States, brought over from the Caribbean by Spanish conquistadores and infused with European flavours by settlers in the New World. But it’s the deeply personal customs of the South that bond it so tightly to their culture: whether it’s sitting up with your buddies all night barbecuing a hog or building the perfect fire with your dad.

Selection process

When we screech to a halt outside Nashville’s Bare Bones Butcher, my white knuckles turn pink with relief. We’re here because, while grilling is one part of the equation, another, says Pat, is being precise about your ingredients (hence those shrimp road trips). Bare Bones is a whole-animal butcher’s shop that sources from farms within a 30-minute drive, guaranteeing the very freshest meat, which is then broken down by hand within the shop.

Inside, we find butcher Wesley Adams cutting our skirt steak from a steer delivered to him just two hours ago. “That cow was walking around a couple of days ago,” Pat tells me as we watch Wesley working the meat, sweat beading his brow. “You get something from the supermarket, it was slaughtered at least 10 days before, then frozen. The fresher the meat, the fresher the iron, and that lends the flavours.”

When Wesley’s finished, he wraps the steak tightly in brown paper to prevent oxidation, so the ruby-red meat remains in its prime. Ringing up the bill, he tells me that, because skirt steak sits inside the rib plate and gets used a lot, it’s more tender and tastes better. Pat might just add a little salt and oil to the meat tonight, but — in a way that I’ll also come to appreciate is typically Southern — it’s the details that count. He’s chosen the provider, the cut and the butcher with rigour.

Soon we’re pulling into Pat’s driveway, from which I can see his 12-year-old daughter, Daisy, splashing about in the pool. His sons, Wyatt, 13, and Walker, nine, are playing video games inside. Far from the blinding neon and deafening guitar amps of Lower Broadway’s honky-tonks, we’re in Nashville’s green, serene suburbs: all single-level, 1950s ranch houses, a swing-seat on every porch. We head to the kitchen through the hallway, where the kids’ art — the sort parents usually tack up on fridges — lines the walls in frames.

It turns out no one gets away with just eating: they’re all expected to pitch in with prep. Pat begins barking orders, tasking Daisy with toasting pumpkin seeds for the salad, and putting Grace Johnston, his right-hand woman at Martin’s Bar-B-Que Joint, on salsa verde duty. “When I first started working with Pat, I’d been a vegetarian for 10 years,” she confides, using a hand-blender on tomatillos, jalapeños and onions that Pat charred on a kettle grill outside. “Then he put a plate of brisket in my face.” And that was that. Pat gave her a bigger appreciation for food, she says. Making everything fresh is the number one rule at Martin’s — nothing frozen, no microwaves — and it’s bled into her own life. “I made 12 pies from scratch one Thanksgiving,” she says, laughing, “but I love letting people eat it more than I do making it. Food, for me, is a form of love.”

Outside, Hal Nichols — Pat’s most trusted pit protégé — is grilling steak and spatchcock chicken over an open pit. Glowing coals are taken from a separate burner and then shovelled under the meat, imparting less smoke than if the wood had been burned in the same cooker. “It’ll come out with the nuance of being grilled,” Pat explains. It reminds me of something he said earlier: that the key to tonight’s spread is “simple, but with layers of flavour and texture”.

Like Pat, Hal is an imposing figure: hairy, burly, deep bass voice. But he, too, opens up when we get to talking about food. The simplicity of Southern cooking, he says, comes from historical necessity. The Southern life was the rural life, and people ate what they could grow and afford — which wasn’t much.

“My family was very ‘country’ in their approach to things,” he tells me. “It was a family of casseroles: anything that tasted good, you could dump it all in one pan and it’d still taste good.”

Making a lot out of very little is the enduring theme of Southern cuisine, Hal thinks: whether that’s frying chicken to perfection or letting a fine cut of meat sing its own merits, with meticulous prep and cooking. Ritual, as much as the taste, makes it special. “It was an event, when grandma’s high-sided cast-iron skillet came out,” he remembers. “You have to be committed to fry chicken on your stove at home. It destroys your kitchen.”

Meanwhile, Pat’s custom is to salt the steak at the optimal time for optimal taste. How far in advance you salt the meat depends on its density and fat content. “For a skirt, three hours before is about perfect,” he says. “It pulls the seasoning in, so that it isn’t just surface.”

Dinner time

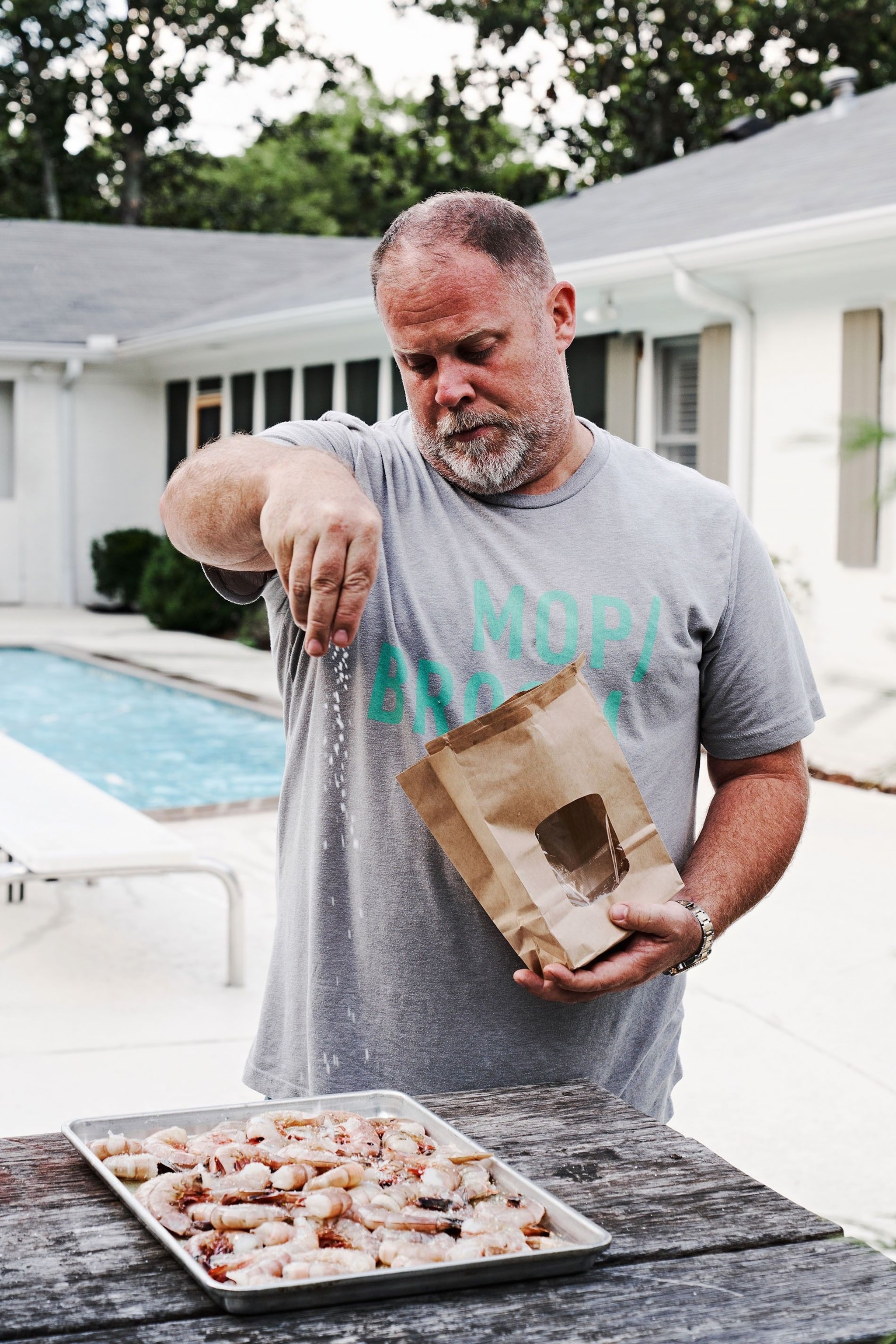

There’s one last job before mealtime, and this time it’s me who’s roped in to help. Pat empties into a bowl his haul of Mississippi Gulf shrimp (this time sourced from Whole Foods Market, not a fishing boat), applying liberal glugs of olive oil and great cascades of sea salt. He then sprinkles the whole lot with his own Memphis-style rib rub — a dry mix of brown sugar, salt and pepper, paprika, cayenne, chilli, mustard powder, oregano, garlic powder and onion powder. I’m called to the kettle grill, where I stand with a bowl and receive the cooked shrimp, heat thickening around me on an already humid night. When Walker decides to squirt me with his water gun, I’m grateful, whether it was meant as a kindness or not.

Food is piled on to sharing platters and we sit around a table as simply and thoughtfully prepared as the meal. There are sunflowers; wine is poured into mason jars. Pat instructs Daisy on how to eat the salad, insisting she fit all the different layers of texture into one bite: leafy bibb lettuce; sweet, white Georgia peaches; bright-pink home-pickled red onions; her toasted pumpkin seeds; corn kernels smoke-roasted over the open pit. The steak is tender and juicy in a way you dream of but rarely get. And that chicken: as promised, there’s just the subtlest hint of smoky flavour, lurking somewhere between the surface of the crinkly, perfectly browned skin and the tender meat underneath (those contrasts being another happy consequence of open pit cooking). Dousing it in Grace’s smoky-spicy salsa adds more flavour, more texture.

As the light fades and the wine flows, it seems that everyone has a story about a wonderful family recipe. Pat’s wife, Martha, recalls her grandmother’s fudge pies; Pat’s mother made “legendary biscuits”. Nostalgia, I realise, plays its own powerful part in Southern cuisine. They don’t call it ‘comfort food’ for nothing. It’s even why Pat, previously a ‘finance guy’, risked everything to start a barbecue restaurant.

Most of Tennessee’s old, whole hog barbecue joints had gone by the time Pat graduated college in 1996, he tells me. “Barbecue has always been America’s peasant food — it’s expected to be cheap,” he explains. “My dad’s generation was old barbecue guys with old barbecue joints. But my generation went to college. And that new generation wants to know, ‘Why work my tail off cooking for 24 hours to charge $2 for a sandwich?’”

But there was obviously a hunger for those flavours of the past: Pat’s restaurants place the pits upfront so patrons can see tradition at work and smell the smoke. Maybe it’s because Nashville is changing so quickly — with all the clogged roads and construction work to prove it — that they’re newly willing to pay for that connection to something so deeply ‘old Nashville’ (if Pat’s pool is any indicator). He’s not just in it for profit, though: part of his legacy is the pitmaster training programme — of which Hal is a graduate — set up in order to pass these skills on to the next generation. “The Nashville-ness of our city is being sold away; it’s starting to lose its soul,” he says. “Preserving whole hog is preserving my view of life and culture.”

The food on the table is finished, but wine is still being poured and the chat wanders over the devastation of shrimp shells and chicken bones, turning to local gossip. There’s the tale of this guy who wound up in court drunk; that mother-in-law who mistakenly consumed half a bottle of limoncello and pronounced: “That lemonade was awful.” Grace refers to Hal as her “brother from another mother”. Everyone around this table is family, bonded by food

Pat’s charred salsa verde

In Mexican cuisine, salsa is treated more as a seasoning than a sauce, adding acidity, heat and salt.

Serves: 6-8

Takes: 35 mins

INGREDIENTS

10-12 large tomatillos, husked and rinsed

½ large white onion, outer skin removed

3-4 jalapeños, to taste

3 garlic cloves, peeled

8 tbsp chopped fresh coriander

METHOD

1. Lightly char the tomatillos, onion and jalapeños for 15-20 mins, constantly rotating them with quarter-turns to ensure each side gets repeated blasts of heat (this will make the difference between char and burn).

2. Remove from the grill and allow to cool slightly.

3. Deseed the jalapeños.

4. Roughly dice the tomatillos, white onion, and jalapeños.

5. Tip the charred ingredients into a blender along with the garlic and coriander, and blitz until almost smooth. Season with salt to taste.

Four Nashville flavours to try

1. Nashville hot chicken

Fiery fried chicken is pure Nashville. That distinctive, rust-red tinge? Lots of cayenne pepper. Prince’s Hot Chicken has been dishing up the wildly spicy original for almost 100 years, while Hattie B’s serves a more accessible range of heat levels.

2. Buttermilk biscuits

Best described as a savoury scone, but lighter, biscuits are a Southern staple often eaten at breakfast or with fried chicken. In Nashville, though, they’re served any time of day with gravy or jam, or unadorned. The key, Pat says, is to make them “fluffy, not flaky”, with firm sides that rise tall in the oven.

3. Meat ’n’ three

Found across the South, cafeteria-style restaurants offer a daily-changing menu of Southern comfort food. Patrons grab a tray and pick a meat with three sides: anything from country ham and meat loaf to fried green tomatoes and creamed corn. Nashvillians swear Arnold’s Country Kitchen is the nation’s best: one bite of the outrageously cheesy cauliflower casserole confirms as much. End with the indulgent chess pie, a classic that tastes like it’s made of 90% butter and sugar.

4. Duke’s mayonnaise

Southerners believe in only one mayonnaise brand: Duke’s. Created in South Carolina in 1917, it uses more egg yolks than most, with a creamier, tangier result. At Pat’s meal, tomato slices topped with Duke’s and toasted hemp seeds was a standout dish. However, the tomato and mayo sandwich is more traditional.

How to do it

British Airways flies non-stop from Heathrow to Nashville. The Downtown Sporting Club hotel offers doubles from $347 (£279) a night, room only. visitmusiccity.com

Published in the January 2020 issue of National Geographic Traveller Food

Follow us on social media