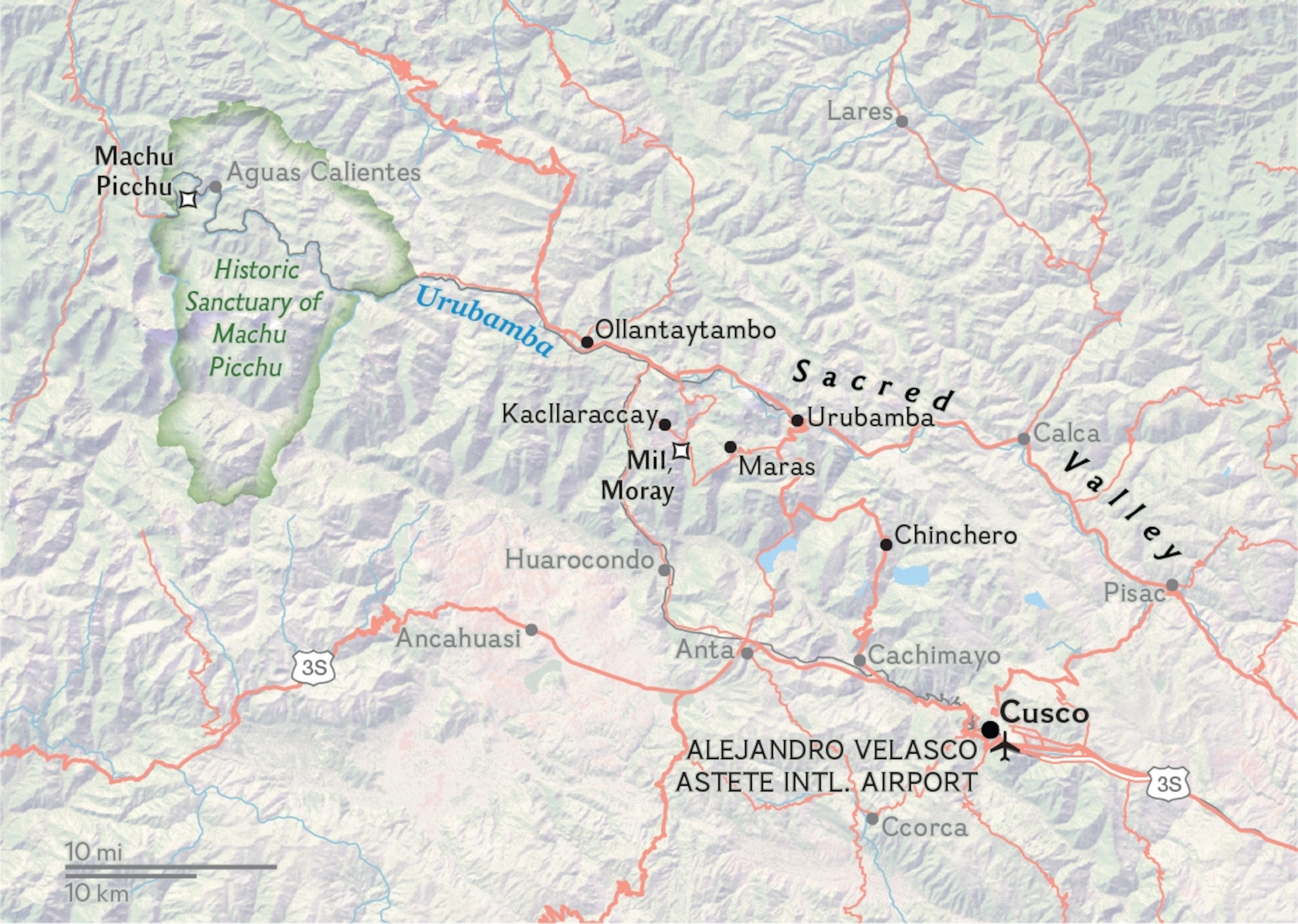

Generations of travelers have come to Peru’s Sacred Valley, which stretches from Cusco northwest to Machu Picchu, to see the intricate stonework the Inca left behind. In their wake fast-food joints and restaurants catering to a Western palate have sprung up. Peruvian farmers have taken to planting white spuds instead of the heirloom potatoes in a rainbow of colors that their ancestors cultivated.

Fried chicken and fries may be delicious but so is guinea pig. This was one of the main things I learned from my first trip to Peru in 2018 when I’d stayed in a Quechua village a few hours’ drive and a short hike from Cusco, working on a National Geographic Society–sponsored project to study shifting trends in indigenous Andean food with National Geographic Explorer Rebecca Wolff. Everything I ate in each dirt-floored Quechua kitchen was memorable, from fire-seared duck to heirloom potatoes roasted in a sod huatia oven to simple barley soups spiced with ají chiles. Now I was back in the Sacred Valley to get a fuller taste of the Inca’s living culinary heritage. (Read about the top 5 places to visit in Peru.)

Recently a group of chefs has committed to stemming the tide of globalization, by elevating traditional foods in the Andes into what has been dubbed Novoandina cuisine. One of these pioneers is Virgilio Martínez, the celebrated chef of Central in Lima, Peru’s coastal capital and gastronomic hub. Last year he opened a new outpost in the center of the Sacred Valley, on a dirt road an hour and a half from Cusco—the 11,150-foot-high capital, ringed by the tall peaks of the Andes, has been continuously inhabited for some 3,000 years.. Each course at Mil highlights a different landscape of the Andes and, in doing so, subtly points to a path through the region by singling out farmers and others whose visions align with Martínez’s exploratory mission.

With notes cribbed from Martínez’s menu, I put pushpins on my map, building an itinerary that I hoped would guide me to the cutting edge of Peruvian cuisine.

Cusco

I didn’t have to go far for my first stop. The only place in Cusco pinned on my map was Three Monkeys, Martínez’s coffee supplier. Plenty of hipster cafés in Cusco can pour a solid shot of pure Peruvian espresso, particularly in the chic San Blas neighborhood uphill from the Plaza de Armas, but I found Three Monkeys closer to the center of town, down the narrow, cobblestoned Calle Arequipa.

I passed a woman in bright traditional dress offering tourists the chance to take pictures of a llama and then I entered a massive wooden door. In an ages-old, arched antechamber that led to a courtyard, Yuri Jacinto Huaytalla ground fresh beans and poured me a silky latte.

Three Monkeys sources beans from farmers in the region, one of whom, Dwight Aguilar Masias, won the top two spots in Peru’s national Cup of Excellence competition in 2018. A sign on the counter told me that the coffee I was drinking was grown and washed in the nearby mountains by Julian Huaman Turpo.

“We wanted to go back to the origins,” said Diego Fernando, one of Three Monkeys’ three founders, “to promote Cusco as the best place for coffee in Peru.”

I sat down with my cup in front of a psychedelic rainbow mural that depicted a character offering up a steaming bowl—grains? a frothy cappuccino?—to the gods. The building was originally part of an Inca palace and was remodeled by the Spanish in the colonial style. Now Three Monkeys shares it with a collective of artists, musicians, and chefs who have a locally sourced and consciousness-expanding vision. The mural seems to reclaim the building as distinctly Cusqueño, calling on the long history of the space but with contemporary echoes.

I finished my latte, savoring the last bold, fruity notes, before heading farther into the Sacred Valley.

King of potatoes

The Inca were deeply invested in eating well. I realized this while driving past steep, terraced fields on the way to Chinchero. In some places, water still runs through their elaborate, centuries-old irrigation canals and pipes. The mountains of the Urubamba range towered above the road, demanding that I crane my neck out the window of the car to glimpse their summits. Some, such as Chicon and Sahuasiray, are over 18,000 feet tall; some were revered by the Inca as gods, or apus. (What to eat and where to get it in Peru.)

Fried chicken and fries may be delicious but so is guinea pig.

Pavel Caceres, my taxi driver, explained that the Inca built an extensive network of roads, bringing bird guano and seashells from the coast all the way to the mountains to enrich the soil. It’s said that some Inca kings, with a relay system of swift mail runners who could carry packages more than a hundred miles in a day, even ordered fresh fish for dinner in their mountain homes in Cusco.

Although the ruins of the Inca town of Chinchero are impressive, I bypassed them this time and stopped instead at a potato farm. The humble plant got its start a few hundred miles southwest near the shores of Lake Titicaca, and botanists have recorded more than 3,000 potato varietals in Peru alone. I wanted to meet Manuel Choque, a farmer who is working to increase that number.

When I hopped out at his family farm, Choque excitedly started showing me the most brightly colored spuds I’d ever seen. For over a decade, he has collected 350 obscure varietals from villages throughout the Sacred Valley. Like a modern Gregor Mendel of potatoes, he has been crossbreeding them, pollinating them by hand to try to improve taste, nutrition, and color.

Idaho-style white potatoes have become popular among farmers in the region as tastes have shifted toward international staples such as pasta and rice. Though still typically native species, the bland spuds lack the nutritional value of the more colorful potatoes that have been favored here for centuries.

Choque passed me a basket of his roasted potatoes. A yellow one burst with flavor when I popped it in my mouth, and a purple potato leaked juice that stained my lips. “Compared to the potatoes without pigment, these ones have 10 times more vitamins and also antioxidants,” he said, which could radically change the lives of subsistence farmers who often struggle with adequate nutrition.

Choque gave Martínez’s team at Mil 50 different types of his potatoes to plant in partnership with the farmers who live near the restaurant. Perhaps, Choque explained, the celebrity chef could shift the market and help reintroduce native potatoes into the local diet.

Maras and Moray

The biggest weekly market day in the region is Wednesday in Urubamba, a lively town in the central Sacred Valley. Quechua families who mostly farm for subsistence sell their surplus crops and buy imported foods, goods from other towns, and fruits from the jungle. In the market’s potato section, women mostly sell huge sacks of the familiar round white potatoes for a few dollars, but a few sell native species in different shapes and colors. (Read how female farmers are feeding the world.)

We passed through the center of town and Caceres turned our taxi off the main road. I checked my seatbelt as he sped up a winding track, overtaking a tractor on the steep inclines.

As the switchbacks leveled out, we drove through the stone streets of Maras. Even before the Inca, the people here found a way to turn water into salt by guiding a mineral-rich stream into shallow evaporation pools. Each salinera is family owned, all still in operation, handed down through the generations.

We rolled across a fertile plateau until we were next to a massive depression in the land, an archaeological site called Moray. I got out of the taxi and looked down more than a hundred feet into a pit with an array of concentric circles of terraces. The site is somewhat mysterious. As you walk down the path on the edge, the temperature starts to drop. Scientists have found evidence that different levels have different soils, some that seem to have come from other parts of the Andes. The best guess is that this allowed the Inca farmers to grow a more diverse set of crops than would normally thrive above 11,500 feet, and perhaps to conduct some agricultural experiments.

The terrace circles are more than 700 feet across at the widest point, and I scrambled around the rim. At the far side of the site, farmers were plowing fields. They poured me a cup of chicha, homemade corn beer—an ancient tradition of welcome-—and we sat on sacks of potatoes, trying to imagine what crops, whether fantastic or mundane, might have grown there.

Mil is perched on the other side of Moray and surrounded by farms. At Virgilio Martínez’s first restaurant, Central, the chef collected ingredients from around Peru and arranged them into courses by elevation. At Mil, Martínez seems to invite guests to travel dusty roads and go into the field with him to explore food, from the Urubamba market, through Maras, and up to the restaurant and beyond.

Walking in, I passed through a hallway hung with dried plants—some recognizable, like quinoa, and others more obscure—and was ushered into a room filled with crop samples and mounted herbal specimens. In parallel to the restaurants, Virgilio’s sister, Malena, runs a nonprofit research group, Mater Iniciativa, that connects with indigenous communities to find ingredients and techniques that might be new to the modern kitchen. Their staff anthropologist, Francesco Dangelo, works out of Mil, studying the neighboring Quechua towns and coordinating researchers who come from around the world to collaborate.

“We want Mil to be the restaurant that people go to for a better understanding of what’s going on in the Andes,” explained Virgilio. “There is so much diversity. We can do impressive stuff with Andean people and products.”

In the rustic-chic dining room with its windows facing out onto the snow-dusted mountains and the Inca terraces, I sat at a polished table made of variously colored types of wood.

“Throughout the experience, we bring out traditions,” said waiter Riecel Damian, laying out simple earthenware and then serving the first dishes: rich, melt-in-your-mouth coca bread with tangy uchucuta butter, a cube of sweet corn, and crisps made from chuño, potatoes freeze-dried in the dazzling sun and cold nights of the mountains. (A blessing or a curse? Discover the history behind the Peruvian coca plant.)

Each of the eight courses on the menu transported me from one part of the Andes to another via ingredient-forward dishes. Duck in black quinoa served with blue-green algae and kale chips took me to a high-altitude lake. Frozen granules flavored with kjolle brought me to the foot of the glacier where that herb grows. A hot stone, partially hollowed out and packed with clay and topped with four kinds of potatoes, called up the smoky, earthen huatia ovens that Quechua families build for parties.

The menu has real implications for those who live in the area, with the potential to renew market value for traditional crops as well as to introduce new food varieties, like Manuel Choque’s potatoes.

Courses come paired with drinks that, when I was there, included two seasonal beers from Cervecería del Valle Sagrado (a short hike away, according to some of the staff at Mil): a red that included seeds from the cactus fruits that grow wild in the mountains and an IPA brewed with passion fruit from the Peruvian jungle.

As the final plates were cleared away, I looked out the window toward Moray, marveling at the range of flavors that generations of people had squeezed from the harsh mountain environment.

Ollantaytambo

At the northwestern end of the Sacred Valley, the town of Ollantaytambo juts out over the Urubamba River. It was there that the Inca won their biggest victory over the Spanish army. Caceres guided the taxi through the main square, past English Pub and Restaurant Quinua Pizzeria, and dropped me in the traffic jam by the rail station. I jumped out and dodged wheeled suitcases and overstuffed backpacks waiting on the platform for the next train to Machu Picchu.

My goal: El Albergue Ollantaytambo, the town’s oldest hotel, which also houses, in a barn out back, Destilería Andina.

Inside the distillery, the atmosphere was pure experimentation. Honeyed light played off of two small stills and countless bottles, filled with alcohol and herbs, that lined every shelf and packed every corner. Andina produces cañazo, a traditional Peruvian rhum agricole, a rum made from sugarcane juice rather than molasses. It is rapidly disappearing from home stills in the mountains as international spirits flood the market.

Resident distiller Haresh Bhojwani was born in Pakistan, was raised in the Canary Islands, went to college in Wisconsin, and worked as a lawyer in New York City before falling hard for the Sacred Valley and its relaxed lifestyle. He began working with El Albergue Ollantaytambo to make a cañazo-based compuesto digestive. But when he tried to source spirits from distillers in the mountains, he discovered that the craft was dying and realized that “unless you grab it now, it’s going to be gone forever.”

Bhojwani quickly set out to save cañazo by redistilling locally made alcohol and taking a finer cut that would boost the moonshine for international tastes. He also realized that there was room to create something new. Unlike tightly regulated spirits such as Scotch or Champagne, cañazo is not defined by denomination of origin laws. Bhojwani figures that gives him carte blanche to innovate. (Read more on how Scotland is bringing back its lost alcohol.)

“We’re going to create a language of Andean spirits,” he said. “Here’s the dictionary.” He poured me a glass of smoky cañazo macerated with quinoa and filtered through burnt corn leaves. Then a salty shot that had been aged with fresh cheese. Then a deeply caramelly sip flavored with pumpkin seeds. He’s working on a spirit that interprets the taste of his favorite soup at the market. He showed me a bottle in which dried fish from Lake Titicaca bobbed. Though the spirit finished with the expected flavor of drying fish, it led with rich plums and dried apricots.

Bhojwani took me to another corner, excitedly pouring a nip of cañazo aged in Andean cherry wood, rather than traditional oak. It was unlike anything I had tasted before: effervescent, lightly floral, purely Peruvian.

At Mil, they serve Bhojwani’s cañazo mixed into a cactus fruit cocktail with the first course and then offer a small pour of his compuesto to follow a fatty, crispy pork belly dish.

We stepped outside to watch a group of cooks finish roasting pork, chicken, lamb, and fava beans in a traditional earthen pachamanca oven on a bed of hot stones. I tasted carefully, trying to imagine if any of these Andean flavors might someday end up in one of Destilería Andina’s drinks.

That night, as train whistles blew, signaling a stream of departures to Machu Picchu, I walked through town, passing tchotchke shops with stuffed llama toys and restaurants advertising BLTs and guacamole. I recalled that Ollantaytambo has some of the longest continually inhabited houses in South America. I had run out of pins for my map, but some of the team at Mil had suggested I stop at Chuncho on Ollantaytambo’s main square.

Bhojwani was already at a table upstairs, and I joined him and Joaquin Randall, a partner in the distillery and Chuncho’s owner.

Chuncho’s bar was built from the wooden back of a produce truck, and the bartender grew up herding sheep in the mountains, but Chuncho serves the type of craft cocktails that launch downtown speakeasies. Bartenders create with only local ingredients, from Bhojwani’s cañazo to whatever mixers they can figure out how to make in-house. Bhojwani and Randall ordered the gingery, refreshing Waris—close to a Moscow mule—and I opted for the layered Matacuy sour, which mixed an herbal digestive with citrus bitters.

The server brought out a tray with finger foods that looked like the snacks farmers eat in the fields around town: massive boiled corn kernels, fava beans, salty cheese, alpaca charky (jerky). Next to arrive was a hearty but complex pumpkin soup with spicy rocoto peppers.

“It’s just like mama’s cooking here,” said Randall, dipping fava beans in spicy huacatay sauce.

His parents moved from the United States to the Sacred Valley and have been running El Albergue Ollantaytambo at the rail station for decades. Randall was born in the hotel and, after a lifetime of re-creating European-style dishes for guests there, he decided to open Chuncho to shine a light on local foods. Most of the ingredients come from the organic farm next to Destilería Andina.

Chuncho means “native” or “wild” in Quechua, and the restaurant aims to serve purely traditional dishes. “These are foods that you only eat once a year,” explained Bhojwani. Such specialties are mostly reserved for festivals, but locals get a discount every day at Chuncho, which has made it one of the only restaurants where Sacred Valley natives and tourists mingle.

Chef Josefina Rimach, who grew up in a subsistence farming village a short hike from Ollantaytambo, came out of the kitchen smiling, with a platter of small dishes including roast lamb and guinea pig.

“Instead of French techniques on Andean ingredients, this is Andean techniques on Andean ingredients,” said Bhojwani.

Virgilio Martínez’s restaurant may be the best known for leading the charge of Novoandina cuisine in the valley, but I realized that Chuncho is the next wave. The recipes haven’t been honed in Michelin-starred kitchens, but passed down through generations and plated simply and beautifully—uniquely Peruvian food made by locals meant for their neighbors, but enjoyed by their visitors as well.