What role do tourists play in the future of Confederate monuments?

At Stone Mountain—Georgia’s most visited attraction—visitors navigate race and responsibility in the shadow of a massive Confederate carving.

For Tina Fears, Stone Mountain is a place of contradictions.

When Fears was a child at Stone Mountain Elementary School, she could walk outside and see the massive dome: Its moonlike, 800-foot-tall surface juts out from the surrounding trees. Her father took her and her sister fishing at a lake in Stone Mountain Park, in the monolith’s shadow, just past the historic covered bridge constructed by prominent Black businessman Washington W. King.

But on the other side of the mountain towers a monument to those who fought to keep Fears’s ancestors enslaved: a carving of Confederate President Jefferson Davis, General Robert E. Lee, and General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson on horseback, hats over their hearts. Nine stories tall and three acres in surface area, the high relief sculpture is the world’s largest.

For park tourists—many of whom are people of color—Georgia’s most visited attraction can invite conflicting emotions: awe at its natural splendor, comfort from seeing the array of friendly, diverse park staff and guests—and bitterness at how white supremacists have marked it as their own. The state-owned monument has weathered years of debate about whether or how to remove the Confederate carving, but there’s no clear answer in sight. And, increasingly, tourists are wondering where they come in.

“We are not by any means oblivious to the fact that someone got up and put that carving there, and that was something that the community approved,” Fears says.

A complicated history

Like most Confederate monuments, Stone Mountain wasn’t built right after the Civil War. Instead, it was suggested decades later, as Southern states enacted Jim Crow laws to suppress Black people’s newly won federal rights.

In 1914, a member of the United Daughters of the Confederacy began efforts to place a bust of Robert E. Lee on the mountain. A year later, Stone Mountain’s peak hosted the rebirth of the Ku Klux Klan, whose burning crosses heralded renewed commitment to a system of violent oppression against Black people. Plans for the sculpture moved forward, expanding to include Davis and Jackson. Decades of delays (partially due to a lack of funds) stalled completion of the carving until 1972—eight years after the 1964 Civil Rights Act and 18 years after the Supreme Court ruled segregation was illegal.

Clark Hill, a local resident and frequent visitor, has been going to Stone Mountain Park for more than 60 years. His first memory of the site is when he was five, in 1955, just before the state of Georgia bought the mountain from a private owner. He remembers the park’s beauty—the songbirds and now-endangered lichen and mosses—but also the Confederate flags and T-shirts for sale at the time. As he got older, Hill, who is white, understood the pro-slavery ideology that those symbols represented. He sees the carving as “the most shameful desecration of a natural resource imaginable.”

(Related: Here’s how Jim Crow laws created “slavery by another name.”)

But the park’s racial dynamics are more complex than the carving’s history. The town of Stone Mountain sits in Atlanta’s northeastern suburbs—one of the most diverse areas in the Southeast, home to Black, Asian, and Latinx immigrant communities. It’s common to hike the mountain on a weekend and hear chatter in Spanish, Korean, Gujarati. (Since the pandemic has curbed national tourism, a majority of park visitors are local—though regional tourism has increased steadily in recent months, according to Stone Mountain Park.)

As those communities grow, the park increasingly is marketing itself as a family destination. Its 3,200 acres contain a golf course, fishing lakes, and 15 miles of wooded trails. But there’s also a variety of retail and entertainment—museums, food, theatrical performances, and a famed laser light show—run by Herschend Family Entertainment, a private company which also operates Tennessee’s Dollywood. Although the pandemic has closed most of the park’s commercial attractions, more people are visiting the park’s natural assets.

If you’d only like to hike up the mountain, the park’s configuration makes it possible to ignore the Confederate memorial—though, to get to the walk-up trail, you’d still have to take Robert E. Lee Boulevard and pass the Confederate Hall education center.

Following the money

Adjoa Danso’s relationship with Stone Mountain has grown increasingly complex over the years. The social media coordinator’s family would visit often when she was a child; as Ghanaian immigrants, they didn’t immediately understand the site’s history. But after seeing years of protests against police shootings and white supremacy, Danso has found that the park’s $20 parking fee (or $40 annual pass) takes on a new weight. “I’m thinking about where that money is actually going in a way that I wasn’t before,” she says.

(Related: As statues get torn down, which monuments should we visit?)

The Stone Mountain Memorial Association, the state authority which has governed the park since 1958, says the park supports itself without tax dollars, receiving about $50 million in revenue from about 4 million visitors every year.

Some have raised concerns about potentially losing revenue if the carving were removed—though it’s unclear how many visitors come primarily to see it. The park’s status as a public-private partnership obscures some of the finer details, too. When asked for financial data that might include what proportion of park fees is spent to maintain the carving, SMMA CEO Bill Stephens wrote in an email that Herschend Family Entertainment declines to provide that information.

Alykhan Pirani, a college student who grew up in Stone Mountain, says that his Indian immigrant family decided not to pay to enter the park anymore after talking about the Black Lives Matter movement. (Only vehicles pay to enter; bikers and walkers don’t.)

By paying, “we’re supporting the monument, which is a monument to white supremacy [and] slavery,” he says, emphasizing the need to prioritize Black voices in questions about the carving’s future.

For others, the park fee isn’t an issue.

“The place is not the carving,” says Nicki Salcedo, an author who also grew up near the area. Although she’d rather have the carving removed, she says it—and the larger debate about taking down Confederate monuments—can distract from more urgent issues like poverty or gentrification, or from celebrating the progress Black and brown people have made. Visitors are better served by deriving much-needed peace and restoration from the park’s natural beauty, she says.

(Related: Here’s why toppling statues is a first step toward ending Confederate myths.)

“It’s this amazing piece of granite, that is prehistoric, that’s come out of the ground,” she says. From the top of the mountain, she can see dozens of miles on a clear day, including views of the Atlanta skyline. For her, the mountaintop is a sacred space, as it may have been for the Indigenous peoples whose ancient artifacts have been found on the mountaintop and who existed long before the Confederacy. And the people who make up the park’s visitors—majority nonwhite, in her experience—make her feel at home as a Black woman.

“I never felt unsafe,” she says. “It [is] always a joyous place.”

Proving ground

Despite its diverse crowds, the park’s pro-Confederate history still makes it a favorite for right wing gatherings.

In August, as white supremacist and other groups applied for a permit to host a rally at the mountain, SMMA closed down the park instead (a common tactic in recent years). The rally instead spilled out into the majority-Black town of Stone Mountain, where the groups were met by counter-protestors and riot police intervened.

(Related: Read the fascinating origin story of Monument Avenue, America’s most controversial street.)

This summer’s protests against police brutality—including two high-profile cases in Georgia—have restarted efforts to remove the country’s largest Confederate symbol. Over the years, locals have proposed solutions: sandblasting the carving away or surrounding it with images of civil rights heroes (or even beloved Atlanta hip-hop group OutKast).

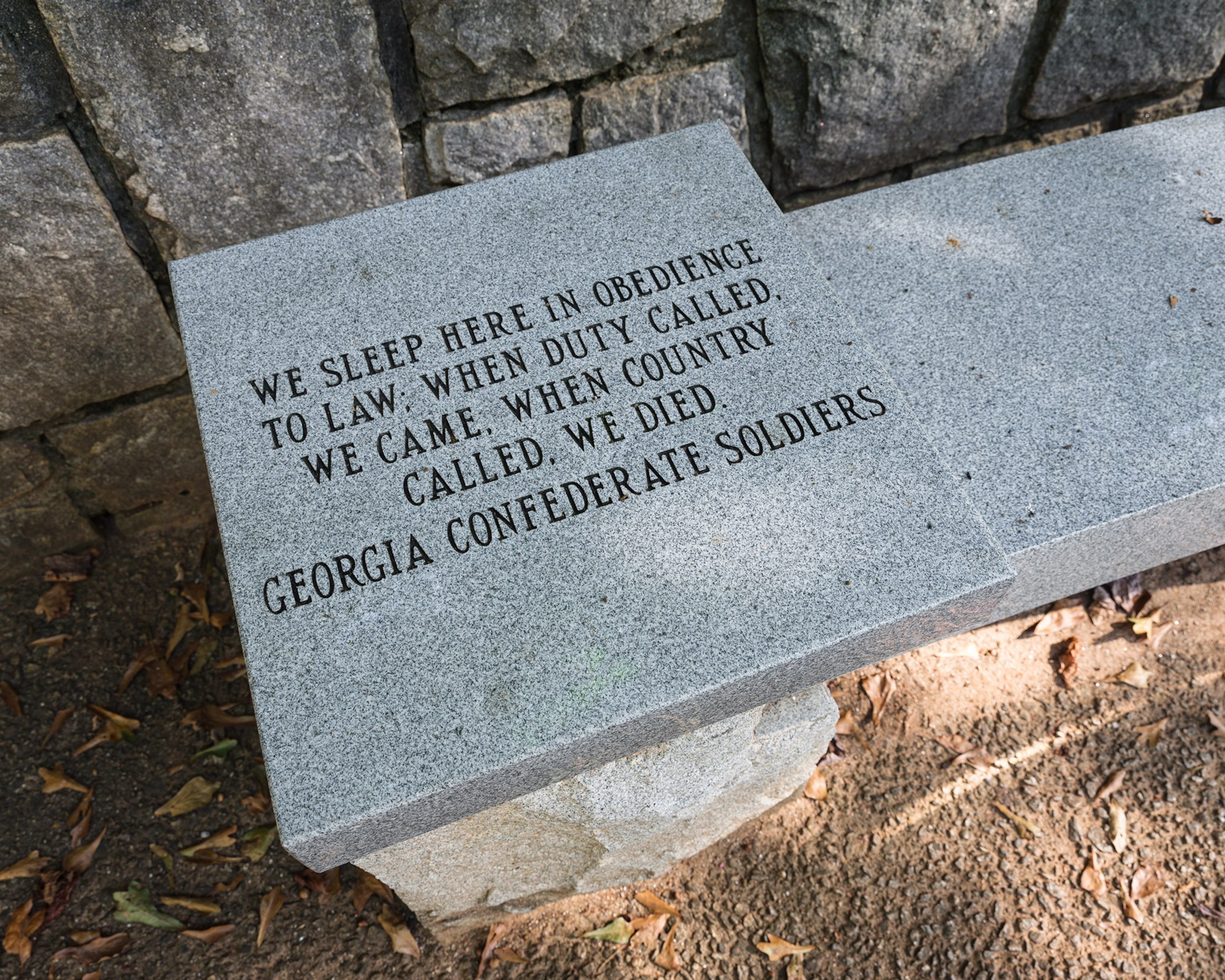

But since 2001, a much-challenged state law has protected the carving, which can “never be altered, removed, concealed, or obscured in any fashion … as a tribute to the bravery and heroism of the citizens of this state who suffered and died in their cause.”

The newly formed advocacy group Stone Mountain Action Coalition would like the park to rename its Confederate-themed streets, issue an anti-racism statement, and simply stop maintaining the carving to let nature reclaim it. Otherwise, “Stone Mountain will continue to be a lightning rod” that attracts rightwing groups, says SMAC cofounder Martha Shockey.

State legislators and the park’s operators ultimately hold the power to change the carving. In the meantime, its history forces many tourists to assess whether their presence, payment, or simple enjoyment of nature counts as support for the Confederate monument. In this public space, what would removing the monument achieve?

Fears isn’t sure that the carving needs to go. “We can’t completely get rid of everything, because then we forget,” she says. For her, the carving presents a teachable moment for her nine-year-old son.

She’d like to see the park make a clearer statement on its legacy of white supremacy, rather than continue its awkward balance of commercial appeal and historical context. But she also feels that her presence at the park is special.

“I think it is a way to honor those who came before us, by taking up space and changing what the history of this looks like,” she says. “Because those people on that rock never thought folks that look like me and you would be able to do the things that we’re doing right now. That was never part of their plan.”