Inside the political battle to preserve a sprawling national forest in California

The proposed Range of Light National Monument could be a conservation game-changer.

Both Theodore Roosevelt and John Muir might have applauded a bold proposal currently being fought over in California: Shift control of the 1.3-million-acre Sierra National Forest to the National Park Service, which would manage it as a national monument benefiting species, helping combat climate change, and inching the Biden administration’s “30 by 30 initiative” a bit closer to fruition.

Yet Deanna Lynn Wulff’s Unite the Parks campaign, which treats the national forest as the missing puzzle piece needed to link Yosemite National Park to the north with Kings Canyon to the south, remains politically fraught.

The sprawling national forest in California has thousands of mining claims, timber sales, grazing leases, and private inholdings, activities not typically found in national parks. A private Facebook group formed in 2015 to push back against Wulff’s campaign now has 5,500 members. The forest also lies in the congressional district of U.S. Representative Tom McClintock, a Republican who ardently supports multiple use of public lands and argues that logging is integral to forest health.

But the changing climate requires greater land connectivity to allow species—plants and animals—to retreat to more suitable habitats. Park Service management of the proposed Range of Light National Monument would arguably provide better protection for that connectivity and affected species. In the process, it would help slow the sixth mass extinction.

“It would be a very important step towards 30-by-30,” maintains Stuart Pimm, an expert on global patterns of habitat loss and species extinction based at Duke University. “I think it’s reasonable to say there are substantial concerns about how national forest lands in general protect biodiversity. That’s because, in all fairness to the Forest Service, they have a multiple-use mandate, and biodiversity is not the only part of that mandate.”

(Learn more about how the U.S. can triple its protected lands by 2030.)

Pimm adds that “for many people, the best value for forests is not to chop them down and convert them into wood chips or paper or anything else. The best value of those forests is as forests, preferably old-growth forests, and for the wide range of ecosystem services that those forests provide. This would be a move to increase the fraction of our lands that goes towards that 30 percent.”

An ecological awakening

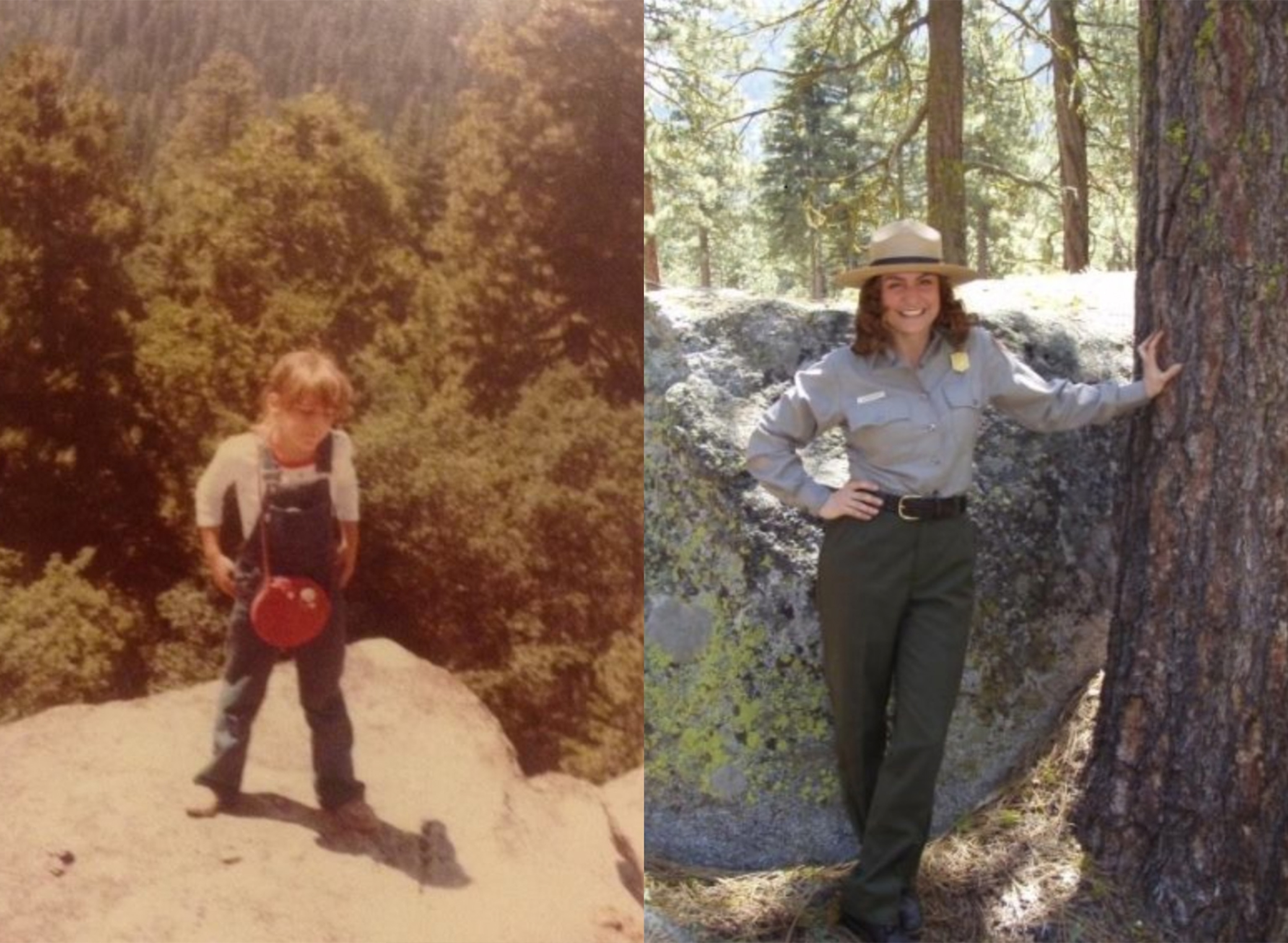

Wulff came to realize her life’s mission while living in her tent on the floor of the Sierra National Forest.

“I’d wake up and the sun would be shining through the trees, and the birds would be singing, there’d be this flow of water,” she recalls. “Chipmunks running around, and the smell of the forest. Such a wonderful smell. This experience altered the rest of the course of my life.”

That was back in the mid-1990s, when Wulff was trying to make ends meet as a waitress in a lodge near Yosemite and called the forest home for a short time during the summer to save money. Today she’s striving to better protect nature by seeing the forest shifted from the U.S. Forest Service—which, she claims, “essentially functions as an agent of the logging industry”—to the National Park Service.

Transforming the national forest into the proposed national monument would create a rumpled, craggy, and forested 2.5-million-acre swath of parklands, or nearly 3 million acres when Sequoia National Park just south of Kings Canyon is factored in.

It’s a stunning landscape that rises to nearly 14,000 feet atop Mount Humphreys. Deep canyons cut through the High Sierra here and drain the boulder-strewn Kings, San Joaquin, and Merced rivers. A quintet of officially designated wilderness areas—Ansel Adams, Dinkey Lakes, John Muir, Kaiser, and Monarch—protect 528,000 acres dotted with sparkling lakes and threaded with hiking trails. There are threatened populations of Lahontan and Paiute cutthroat trout hanging on in some forest creeks, which help nourish more than 1,400 plant species, 82 mammalian species, and nearly 200 bird species.

Adding the forest to the National Park System would also protect the Nelder Grove of giant sequoias, a grove of a hundred or so trees which the Forest Service sees as increasingly important as climate change impacts similar groves in Kings Canyon and the Giant Sequoia National Monument; the roughly 100-mile-long Sierra Vista National Scenic Byway and 70-mile-long Sierra Heritage Scenic Byway that showcase the forest’s high country; and those five congressionally designated wilderness areas.

“It would be the end of commercial logging of the large living trees that still is going on” in the forest, Wulff says of the designation change. “It would remediate and restore the forest, and the ecosystems that support that forest. You’re planting trees, you’re restoring all those native plant species, and supporting all the wildlife that need those big trees and that need those native plant species.”

(Restoring protections for Bears Ears will likely spark legal fights.)

Uniting for conservation

Clipboard in hand and driving a worn-out pickup, Wulff initially pursued her audacious plan with a business-to-business, door-to-door campaign. Today she has a list of 200 or so scientists, researchers, and academics who support her mission, and nearly two dozen congressional backers.

Pimm is one of those proponents. Another is George Wuerthner, an ecologist and author of numerous books on natural history and national parks who says it was always Muir’s intent to see the land between Yosemite and Kings Canyon protected by the Park Service.

“The main reason I support the national monument idea is it would put the entire Western slope and some of the Eastern slope of the Sierra Nevada between Yosemite and Kings Canyon/Sequoia under similar management,” says Wuerthner. “In general, if the national monument were under National Park Service management, I feel we would have a more unified protected area that would guarantee the best management policies we have available to us.”

Wuerthner adds: “As you know, the Park Service’s general propensity is for protection, not exploitation, of the land. The Forest Service, unless it’s designated wilderness, has a much less protective philosophy.”

Although Forest Service staff declined to discuss the proposal, a shift toward more of a conservation approach in national forests is not new. In 1998 then-Forest Service chief Mike Dombeck said that, “We need to do a better job talking about, and managing for, the values that are so important to so many people. Values such as wilderness and roadless areas, clean water, conservation of species, old-growth forests’ naturalness—these are the reasons most Americans cherish their public lands.”

(To keep Earth flourishing, 30 percent of it needs protection by 2030.)

Wulff’s vision comes as the National Park Service faces crowding and overcrowding, with roughly half of the annual recreational visits to the National Park System centered on only about two dozen of the 423 units. (In 2019, 327.5 million people visited the most popular parks, though the COVID-19 pandemic dropped visitation to 237 million in 2020.) During a hearing in late July by the Senate Subcommittee on National Parks, the chairman, Senator Angus King (I-Maine) sounded in favor of easing crowding by adding more units to the park system to give people more room to roam.

“The law of supply and demand doesn’t apply here. The demand is here, but we can’t just go out and build more Glacier [National] parks,” said the senator. “Well, perhaps we need to bear that in mind as this committee and subcommittee considers new proposals for parks across the country.”

That would suit Wulff.

“You get to do this wonderful thing called saving the planet, so we should do it, right?” she says. “There’s no argument against it that makes any sense. The facts are on our side for doing this. It makes sense in terms of the environment, it makes sense in terms of the economy, and I also think it makes sense in terms of spiritual rejuvenation for the nation."

“We need something positive,” she adds. “This could be it.”

Kurt Repanshek is the founder and editor-in-chief of NationalParksTraveler.org, a nonprofit media organization that covers national parks and protected areas.