Journeying through Sicily on a new coast-to-coast pilgrimage route

Take a pilgrimage through the heart of Sicily along the Magna Via Francigena, an ancient coast-to-coast route recently revived by locals.

“It’s here that you can see the real Sicily,” says Miri Salamone, staring into the abyss. Clouds swamp the valley below and fog floods mountain gullies, dissolving even Sutera’s hilly peaks from view. Visibility, as it has been for days in the veiled heartland of Sicily, is about as far as you can kick a stone; something I’ve done regularly in recent days, stumble-walking along mountain ridges in near whiteout, halfway across the interior of the island. “From there,” says Miri, squinting up to the fast-vanishing bell tower crowning the town’s highest point, Monte San Paolino, “you can often see as far as Mount Etna one way and Palermo the other.” She smiles apologetically for the unhelpful weather. “This is the ‘balcony of Sicily’.”

Even with crystal-clear views, you need to look hard to see the ‘real Sicily’ that Miri speaks of. As the Sutera native notes on a soggy tour around her town, this shapeshifting island of many identities is far more removed from the Italian mainland than the few miles of Tyrrhenian Sea would suggest. But here, in the sparsely populated inland, a place few Sicilians — let alone Italians — bother to visit, you’ve the best chance. For along ancient routes cutting a path from the Tyrrhenian to the Mediterranean is a region that tells Sicily's story.

Along the old trade roads and pilgrims’ ways that forge a path through this forgotten land, Byzantine pottery litters the earth; shepherds’ huts sit cheek-by-jowl with churches where religious celebrations owe as much to Moorish Spain as St Peter’s; and local ‘Christian’ names are likely to recall ancient Greek origins. Here in Sutera, about as far from either coast as you can get, the town’s patron saint has Persian heritage and the domed houses of the old town, Rabato, reveal an Arabic legacy, as does the neighbourhood’s name (Rabato comes from ‘rabad’, Arabic for ‘village’). Sandwiched between Europe and Africa, for centuries Sicily marked a strategic point on the world map. Once a colonists’ prize, today the island is infamous, moans Miri, for its regions ravaged by organised crime, and for abandoned rural houses that sell for €1 as part of a drive to reinvigorate Italy’s underpopulated reaches.

Two teens kick a football around a modest piazza that juts over Rabato’s largely abandoned dwellings, which are carved into the gypsum of a breakneck cliffside. Miri stops to point out the boys. “When children are born here — just one or two each year — they’re celebrities,” she says. Teenagers more so, as few resist the bright lights of the coast or the pull of the wealthy mainland. Local legend has it there’s treasure in these hills: a chest of gold hidden in cave-studded cliffs, only to be discovered if three men dream simultaneously of its location. But in this part of Sicily, they can’t wait for a dream. In Sutera and a dozen other villages lining the ancient sea-to-sea roads that slice through the island’s north, they’ve taken fortune into their own hands with an ambitious project to boost tourism: reopening a new walking route along millennia-old pilgrims’ trails.

Ten years ago, a group of Italian friends — historians, archaeologists, naturalists among them — began mapping Sicily’s inland routes as described in the Norman texts of crusading knights. Dating back over 1,000 years, these forgotten trails once formed part of the oldest and most popular pilgrim itineraries in Europe: the Via Francigena (‘the Frankish route’) from Canterbury to Rome and southeast to the Holy Lands. The Sicilian section, a 600-mile network of trans-island roads, paths, trading routes and trazzere (grazing tracks), was used for centuries by everyone from the Greeks to the Romans, Normans, Arabs, Aragonese and more, each leaving treasures and traces that can still be found today.

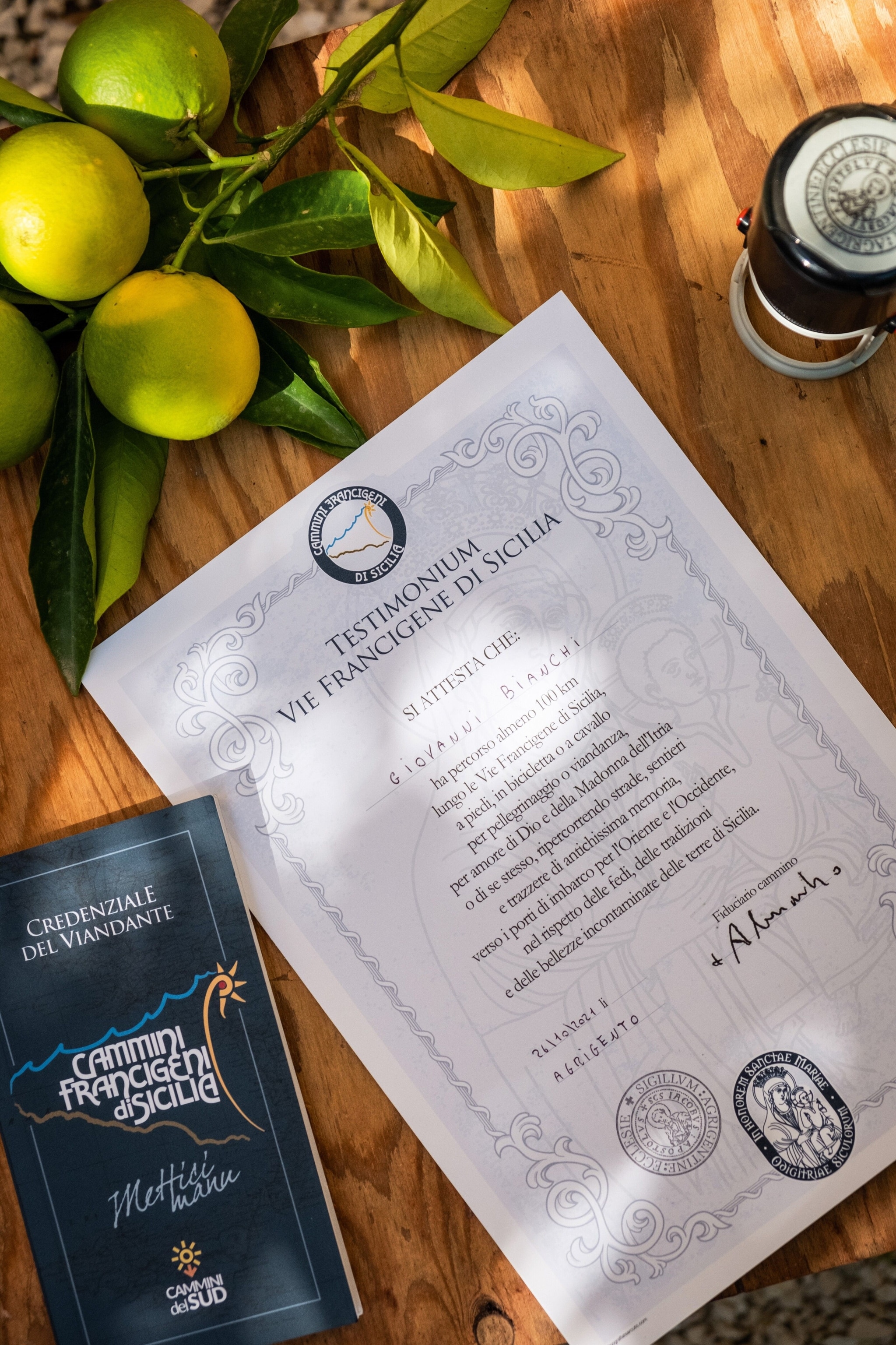

A monumental project to revive the route, involving 80 local authorities and six dioceses, came to fruition in 2017. Along the main artery, the 112-mile Magna Via Francigena, walkers can collect stamps to fill their pilgrim’s passport at participating venues along a route that runs through the island’s north between the coastal cities of Palermo and Agrigento. In the latter’s cathedral, a testimonium certificate awaits triumphant trekkers; hopefully, weather permitting, this will include my friend and me.

Blind faith

My passport gets its first stamp high over the Plain of the Albanians, outside Palermo. The ricotta that stars in Sicily’s most priapic export — cannoli — comes from sheep grazed in these arable lands. Sadly, the sole cafe open in the tiny town of Santa Cristina Gela is out of the sweet pastry treats. By way of substitute, we pack panini for a picnic en route and get our passport stamped by the barista, one of numerous pilgrim-welcoming locals at participating venues the length of the Via, in bars, chapels, shops and B&Bs. On the road skirting hills covered in the wild herbs that give ricotta its earthy-sweet flavour, my luggage has travelled ahead by car to tonight’s hotel, part of a service offered by select operators serving the Via.

It’s late autumn, Sicily’s storm season, and four Belgians are the only other walkers today. “We meet annually to go hiking, mostly around the Mediterranean,” says Mark, an anglophone and the self-appointed spokesperson for the group, with whom we cross paths in coming days. They forge ahead, all utility shorts and well-worn boots, leaving my companion and me to the steady pace we’ve established over years walking together. A clattering storm scuppered our previous night’s sleep, and we set out under a still-bruised sky, bags under our eyes heavier than daypacks, but bolstered by bullet-strong espresso.

The sky threatens again as we climb above Sicily’s breadbasket country, where canyons of palm, aloe and prickly pear cactus look incongruously subtropical among brown wheat fields and muddy livestock. A detachment of semi-feral dogs defends the few shuttered hamlets we pass, their warning barks undermined by wagging tails. The Via’s red-and-white striped waymarks, painted onto posts at frequent intervals, encourage us onwards along dirt tracks becoming indistinct in the mist. A sudden, tree-whipping wind signals a storm seconds before it hits. Clouds roll across the ground like a pyroclastic flow, followed by the kind of rain that has powerful contempt for waterproof clothing. Mud becomes clay, knee-deep and with a quicksand ferocity that claims one of our shoes. Digging it out, it’s barely laced before it must be removed again for us to wade through rising bogs and ford rivers where streams had recently been.

Hours on, the muddy trudge becomes about as fun as poking a stick in your eye (which I know to be true, as this happened while bending to tie a mud-drowned bootlace). Onwards, more blindly than before, we’re saved by a miracle just outside the shrine of Tagliavia. It’s not the face of the Virgin Mary, as seen on a rock here by two shepherds in 1800, but the offer of help via WhatsApp. Finally finding reception, my phone pings with messages from ‘friends’ of the Francigena. Along with trip notes, maps and an offline GPS-enabled app, my tour operator, UTracks, has plugged me into a network of local volunteers, offering assistance to pilgrims with everything from a hot meal to an affordable bed for the night or, when needed, an unofficial SOS service.

“We usually rescue people who’ve overheated,” says Marialicia Pollara, whose four-wheel-drive meets us at the head of a washed-out track. “There’s not a stick of shade en route.” Francigena, quite the Goldilocks walk, is just right in spring, when it’s not too hot, not too cold. “That’s when it’s full of wildflowers,” says Marialicia. “But you’re especially unlucky now.” Instead of autumn’s short-lived storms, we’ve apparently walked into the tail-end of a cyclone, where “a flash flood took a car out last week”. Thanks to winter floodplain detours, the Via is accessible year-round. “But this is crazy weather,” says Marialicia, motoring us out of the downpour, as the priest at Tagliavia’s chapel takes in a Czech pilgrim whose tent stands no chance tonight. At her guesthouse in Corleone, La Bicicletta Rossa, we’re joined by Marialicia’s husband, Carmelo, for a family dinner. Homemade lentil soup and farm-fresh ricotta, drizzled with jade-green olive oil just in from the harvest, is a supper worthy of a waterlogged pilgrimage.

Stories of stoicism

“The Mafia wasn’t born in Corleone — it’s all over Italy,” says Federico Blanda. We’re standing beside a photo of a young man shot dead on a nearby cobbled street. It’s one of numerous blood-splattered images of organised crime in 1970s and ’80s Italy lining the walls at Cidma, the anti-Mafia museum set in a former Corleone orphanage. “I used to hate seeing people here on the trail of Don Corleone — a fictional film character,” says guide Federico. “But I’ve realised we must use the opportunity to tell the real story.” And the real story isn’t one of romanticised Godfather feuds, but one of resistance. Beyond a gut-punching gallery of photojournalism by Letizia Battaglia, a vast archive of court documents details the 474 Mafiosi tried in Palermo’s Maxi Trial — which lasted almost six years — by such steel-nerved judges as Paolo Borsellino and Giovanni Falcone.

“Judges, journalists, campaigners: they paid with their lives for their bravery,” says Federico. Cidma celebrates these fallen heroes, murdered by the Mafia in retaliation. “Back then, we were a population of 10,000; just a handful were Mafia. Yet Corleone’s people still live with the stigma.” He smiles: “So, I love it when visitors come looking for a myth and leave talking about Falcone.”

As the Via brings more visitors, Corleone’s story has more chance of being heard. Stacked spectacularly across tabletop mountains and plunging canyons, the town is a stellar stage on which the Magna Via Francigena zig-zags mercilessly, passing churches and monasteries where pointy-hatted brotherhoods gather in spring for Easter celebrations. “It’s another story little known beyond our island,” says Federico of the region’s Semana Santa processions that challenge Spain’s for pomp and scale, but draw none of the international crowds.

We follow the San Nicolò river as it tumbles from Corleone in a chain of waterfalls that once powered the region’s mills. As small-scale wheat production declined, locals couldn’t turn to the tourism that bolstered the coast. “People don’t arrive here just passing by,” says Totò Greco, another friend of Francigena, whom I meet in the nearby teetering hilltop town of Prizzi, far from any main road. “But now, people can cater to pilgrims.” Prizzi had no hotels previously, so, like Marialicia and many Via locals, Totò transformed a family house into a hip, hostel-style B&B. He’s also set up an association — Sikanamente, named after the surrounding Sicani hills — to incentivise resident youngsters to stay in the area.

At Prizzi’s sizeable archaeology museum, Totò shows off Roman coins and jewellery, as well as other artifacts dating back as far as 5,000 BC, which were mostly found on Sicani’s slopes. I’m particularly taken with a third-century clay-sculpted foot, which bears a remarkable resemblance to my walking boots. Then it’s off to Totò’s cantina to sample this season’s wine. Like a growing number of enterprising young locals, Totò is transforming an old masseria (country farm) into a vineyard, learning how to make wine, reviving native grape varieties and employing local artists to design labels. “You have to create your own path as no one is teaching you how to do things here,” says his colleague, Gabriella Lo Bue. Like many entrepreneurs I meet, Gabriella has recently returned to Sicily after years working abroad, partly due to pandemic constraints, but also because of the prospects the pilgrimage brings. “We all bring skills with us and new ways to promote the region,” she says. “It’s exhausting but exciting.”

These bright new horizons do not extend to the weather. A storm explodes again over Casale Margherita, our next overnight stop, where the owner, Carmelo, refuses to let us continue on foot. “The river’s burst its banks,” he says, chasing us in his pickup truck the following morning. “It’s just not safe — I’ll drive you to the next hill.” Carmelo’s organic farm and gourmet hotel is a new investment. “Tell everyone about us,” he yells, as he waves us off on the hair-raising climb to Sutera. With roads once again running like rivers, we meet the stoic Belgians who jumped a railway track to avoid the river crossing. Raincoats defeated by the endless deluge, they now carry village-bought brollies, one in powder blue with a white lace-effect trim. They trudge away uphill resembling a huddle of old ladies off to the shops.

“Even now, religion is at the centre of our town,” says Miri, when we meet again. “Church bells still shape our day.” Three special bells placed at intervals mark the pilgrims’ climb up Monte San Paolino, over an ascent of 157 steps carpeted with fallen pinecones from which nuts are gathered to make a local pasta with raisins. On reaching the bell at the summit — a one-ton gift from the Vatican — I haul a huge rope pulley, thus sounding a bass chime that makes my teeth shake and sends lizards scuttling through the undergrowth.

Our path is blessed, it seems, from here onwards. Sunlit trails of chalk and shale line rolling hills towards the sea, now looming on the horizon and making my coast-to-coast pilgrimage finally seem like a visible reality. “All of Sicily is a dimension of the imagination,” wrote Leonardo Sciascia, the region’s great novelist, who was born in Racalmuto. I make a pilgrimage within a pilgrimage to his 1930s museum-piece apartment: a highlight of this town, which offers shiny boutiques, palm-shaded piazzas and a grand, 19th-century theatre. Sciascia’s novel Sicilian Uncles has been worth the extra weight in my backpack, painting the island’s complex mid-century portrait, caught between US and German occupation, Italian and Sicilian identities.

“In Sicily, we have many stories of identity and transformation,” says Alessandra Marsala, whom I meet at Caffè Marconi in the little hillside town of Grotte. “Perhaps it’s the influence of Greek legends,” she continues. “Or because so many nations have left their mark here,” adds her dad Carmelo, the cafe’s owner. The old town’s cave dwellings that once housed shepherds gave Grotte its name, but its murals now make the place renowned. Over the past five years, a community project to engage local and international artists has transformed the once-abandoned old town into a vast outdoor gallery. One house has a facade depicting, over two storeys, a snake-woman, recalling the Sicilian legend of La Biddina, a heartbroken girl whose sorrow turned her into a serpent. Many other images are illusions that only appear depending on their angle of view. The energy these murals have brought to this tiny town is palpable.

Also in the air is the scent of mpignolata — pastries filled with fried onion and pancetta that line stomachs on St Martin’s Day (11 November), when the year’s new wines are celebrated. We are, of course, quickly invited to a festive lunch, where handmade arancini and fresh cannoli with local ricotta play starring roles. My English reserve marvels that wherever the Via has taken us, rain or shine, it truly feels as if we’re meeting family. Carmelo drops us at the trail head, first jumping a fence to scrump some corbezzolo for us. Gathering a handful of the gem-like fruit of the strawberry tree, he waves heartily at the distant farmer who looks on, mouth agape. “We’re all family here,” he laughs.

I trail a shepherd and his flock downhill to Aragona, where some of the treasures of Sicily’s wealthiest families are found. Here, local count Luigi Naselli was crowned Prince of Aragona by Spain’s King Filippo IV. His castle, completed in the 18th century, is frescoed by Flemish painter Guglielmo Borremans and surrounded by gothic churches in which ecclesiastical museums shine with decorated ex-votos, Venetian religious robes and even a bejewelled scrap of the Turin shroud. Yet, away from the coast and its stellar archaeological site, Valley of the Temples, Aragona is woefully overlooked. It’s a fine place for a fortifying plate of spaghetti all’aragonese, laced with the region’s legendary pistachio nuts. It’s best sampled at Lo Sperdicchio, a family-run restaurant where pilgrims can touch a lucky wine barrel painted with local saints and get their penultimate passport stamp.

In Agrigento, where the Med shines blue and the Via’s medieval villages feel like a dream, my journey’s end is announced with a locked door. Agrigento’s towering cathedral, where views stretch back to Sutera’s peaks and across to Africa, is shut for renovation. I stand outside foolishly as Agrigento goes about its smartly dressed Sunday business. But as ever, the friends of the Francigena step in. A WhatsApp message pops up, telling me that the cathedral’s pastor, Don Giuseppe Pontillo, will sign my testimonium once he’s finished mass in a neighbouring church. The padre does as promised, ironically warning of the dehumanising dangers of mobile phone communication. I ask him if he’s completed the pilgrimage. He gives me a stern look as if to say: you think I have time for that? “But it is what we all desperately need,” he says. “To make real connections with our world and with each other.”

Getting there & around

Ryanair flies non-stop between Stansted and Palermo. Other airlines, including British Airways, ITA and Swiss serve Sicily seasonally or fly via their European hubs.

Average flight time: 2h50m.

Hourly trains run between Palermo and Agrigento with a journey time of 2h.

When to go

The Magna Via Francigena is accessible year-round. Winter detours take hikers above floodplains, but spring is by far the best time to travel, when the route is rich with wildflowers and storms are scant. Temperatures vary with altitude. As a guide, Sutera — one of the highest points on the route — ranges from around 9C in January to 30C in July.

Places mentioned

Archeology museum, Prizzi.

Cidma

Sikanamente

Casale Margherita

La Bicicletta Rossa

Grotte mural project

Access to Sutera’s pilgrim bells must be booked in advance.

More info

Sicily Tourism

The Magna Via Francigena Trail: Sicily on Foot, From Coast to Coast, by Davide Comunale (Terre). €16 (£13)

Sicilian Uncles, by Leonardo Sciascia (Granta). £8.99

How to do it

Utracks offers self-guided tours of the Magna Via Francigena. Eight days costs £870 per person, including seven nights’ B&B in three-star hotels, B&Bs and an agriturismo. It also includes a road book, maps, navigational app, luggage transfers, emergency hotline and SMS alert and pilgrims passport.

Published in the March 2022 issue of National Geographic Traveller (UK)

Follow us on social media