Meet the people who make the UK's cheese scene so special

From the shop owner with a Covid-friendly cheese vending machine to the creator of a modern British brie, meet the people at the forefront of the UK's cheese industry.

We may not eat as much of it as many of our European neighbours, but the UK’s affinity with cheese is about more than just our daily consumption. The country has a proud history of cheesemaking that stretches back millennia, with our cool, wet climate and lush pastures having helped create one of the world’s richest dairy traditions.

This year, our relationship with cheese evolved, with the food proving a true essential during difficult times. According to figures from Kantar, supermarket customers spent 23% more on cheese during the first 12 weeks of lockdown than in the same period last year, with both British and Continental varieties seeing a surge in popularity. The wider picture, however, is more complex, as the producers of many of the country’s most celebrated artisan cheeses were hit hard by a collapse in restaurant orders. By summer, the scene looked bleak, but the industry rallied, with fromageries, farmers, cheesemakers and regular customers all playing a part in keeping things afloat.

Both history and landscape are wrapped up in the identity of the UK’s cheeses. Cheddar, the nation’s favourite, has its origins in the Somerset town of the same name and in nearby Cheddar Gorge, where it was traditionally matured in caves. Blue-veined stilton, meanwhile, is named after the eponymous Cambridgeshire village. That sense of place is similarly tangible in the names of our ‘territorial’ cheeses, including cheshire, lancashire and wensleydale — historic, singularly British products, made in a manner tailored to suit the realities of our climate and reflecting the dampness of these islands.

In centuries gone by, farmers turned to cheesemaking as a means to preserve milk; this gave rise to the countless farmhouse cheese varieties for which the country was once known. But the 19th and 20th centuries brought with them a move away from farmhouse cheesemaking towards factory production. A government centralisation of cheesemaking during the Second World War, and rationing during and afterwards, had a particularly devastating impact on the farmhouse tradition: much valuable knowledge was lost.

Happily, the past three decades have seen a revival in the UK’s cheesemaking scene as part of a broader, renewed interest in homegrown food and local produce. Modern producers — working on a craft scale — have set about adapting traditional techniques to make new varieties. Today, the Specialist Cheesemakers Association estimates there are more than 200 artisan cheesemakers in the UK, with the scene offering a winning mix of historic varieties, such as double gloucester and caerphilly, alongside new names like Perroche and Berkswell.

So, come and meet the people who’ve done so much to nurture Britain’s cheese scene and who’ve helped to ensure that the UK’s homegrown product is as varied, memorable and delicious as it has been for decades.

Bronwen Percival, cheese buyer at Neal’s Yard Dairy

Thoughtful, curious and articulate, Bronwen Percival occupies a special role in Britain’s cheese world. She works as a buyer and technical manager for Neal’s Yard Dairy — the micro-dairy turned artisan cheese retailer founded by Randolph Hodgson in 1979. And her role involves working as closely as she can with the producers of the 60 cheeses they stock.

Bronwen visits cheesemakers all over the UK, getting to know the cheeses she’s buying. It’s a practice first started by Hodgson, and is a time-consuming yet extremely important part of her job. “It would be super-easy just to pick up the phone,” she explains. “But there’s no better way to maintain our connection than to set foot on the farm, taste through the batches of cheese with the producer and have a conversation.”

Part of Bronwen’s skill lies in understanding how flavour develops in cheeses as they mature, and then choosing accordingly. When tasting Montgomery cheddars at nine months, for instance, she detects fast-maturing ones, which will go for export, and “locked-in, corky flavours, which will taste amazing in several months’ time” in cheeses that will be further matured before being sold in Neal’s Yard Dairy stores.

Bronwen is always keen to help producers develop and improve their cheeses. She cites working with Rob Howard, of Holden Farm Dairy, on his Hafod cheddar as a key example of this collaborative process. “Rob was amazing at reworking the ‘cheese make’,” she says. “Now Hafod is more consistent, but also more delicious, deep, savoury and balanced.”

In recent years, Bronwen has expanded her role, organising a biennial Science of Artisan Cheese Conference. “I realised that British cheesemakers don’t have the technical support that those in France do,” she says. “They have consultants and cheese schools, whereas the UK managed to lose a lot of know-how last century when its farmhouse cheese industry evaporated.”

As for the future, Bronwen has high hopes for the British cheese industry. “We have the potential to go from just a handful of small producers to a community — one that has all the advantages of infrastructure,” she says.

Jonny Crickmore, dairy farmer and maker of Baron Bigod at Fen Farm Dairy, Suffolk

I’m the third generation of dairy farmer in our family. As a boy, I only ever wanted to be a farmer. But after the Milk Marketing Board ended, the milk price was low and the whole industry was negative. I started selling raw milk direct to the public and got 50 times the profit for one bottle of milk that I would have made by selling it to a dairy.

When you have a good idea and it goes well, it’s like a drug. In 2011, we started selling raw milk, and by the end of that year we’d come up with the idea of adding value by making cheese. We went to Neal’s Yard Dairy for advice and Bronwen Percival said there was no one making a British brie — so we looked into it. A cheese consultant told us to swap our Holsteins for Montbeliardes, a French cow with great milk for cheesemaking. I went to France, bought 73 and we started making cheese in 2013.

Learning how to make cheese took years of trial and error. There’s lots to learn. We had to keep experimenting. It’s hard because you’re working with live bacteria to create food, but that makes it fascinating.

Baron Bigod is made using morning milk, still warm from milking. We ladle the curds by hand to keep the moisture in. It’s buttery and creamy. If you eat it between weeks seven and eight, you get a little line of curd inside. The mould growing around the cheese turns it gooey, while the inside is maturing in its own way.

Becoming farmhouse cheesemakers has changed our lives. It took us out of the bubble of farming. Life has been so interesting ever since.

Sarah Appleby, maker of cheshire cheese at Hawkstone Abbey Farm, Shropshire

As one of England’s only remaining producers of raw milk, farmhouse cheshire cheese, Sarah Appleby and her husband Paul are maintaining both family heritage and a regional food tradition.

Paul’s grandmother, Lucy Appleby, came from a family of notable Cheshire cheesemakers. “She and her husband Lance moved to Hawkstone Abbey Farm in the 1940s and turned the stables next to the kitchen into a dairy,” explains Sarah. “She had seven children and could wheel the pram between the kitchen and the dairy. We make our cheese in the same place.”

For Sarah and Paul, it’s important that they’re carrying on Lucy’s legacy. “She’d know what her cheeses would taste like by looking at them,” says Sarah.

While industrially produced cheshire is mechanically made and matured within a week, the Applebys take time at every stage. The process starts with looking after the pastures and their 300 cows. “The whole point of our farm is that we make cheese. We use raw milk because it’s alive. It smells delicious when it comes into the vat.”

Much of the work is done by hand, from the cutting and turning to the breaking and moulding of the curd. It’s then wrapped in calico and matured for six to eight weeks, during which time it’s turned and rubbed daily. “We want each crumb to be delicate and soft, to have a creamy milkiness,” says Sarah. “Cheshire doesn’t have a resistant bite, like cheddar — it’s more giving. We’re looking for that traditional lemony saltiness. The Cheshire plains were salty, and we still use Cheshire salt. I like that minerality and the grassy, herby, cow breath. It reminds me it comes from a cow — comes from a farm.”

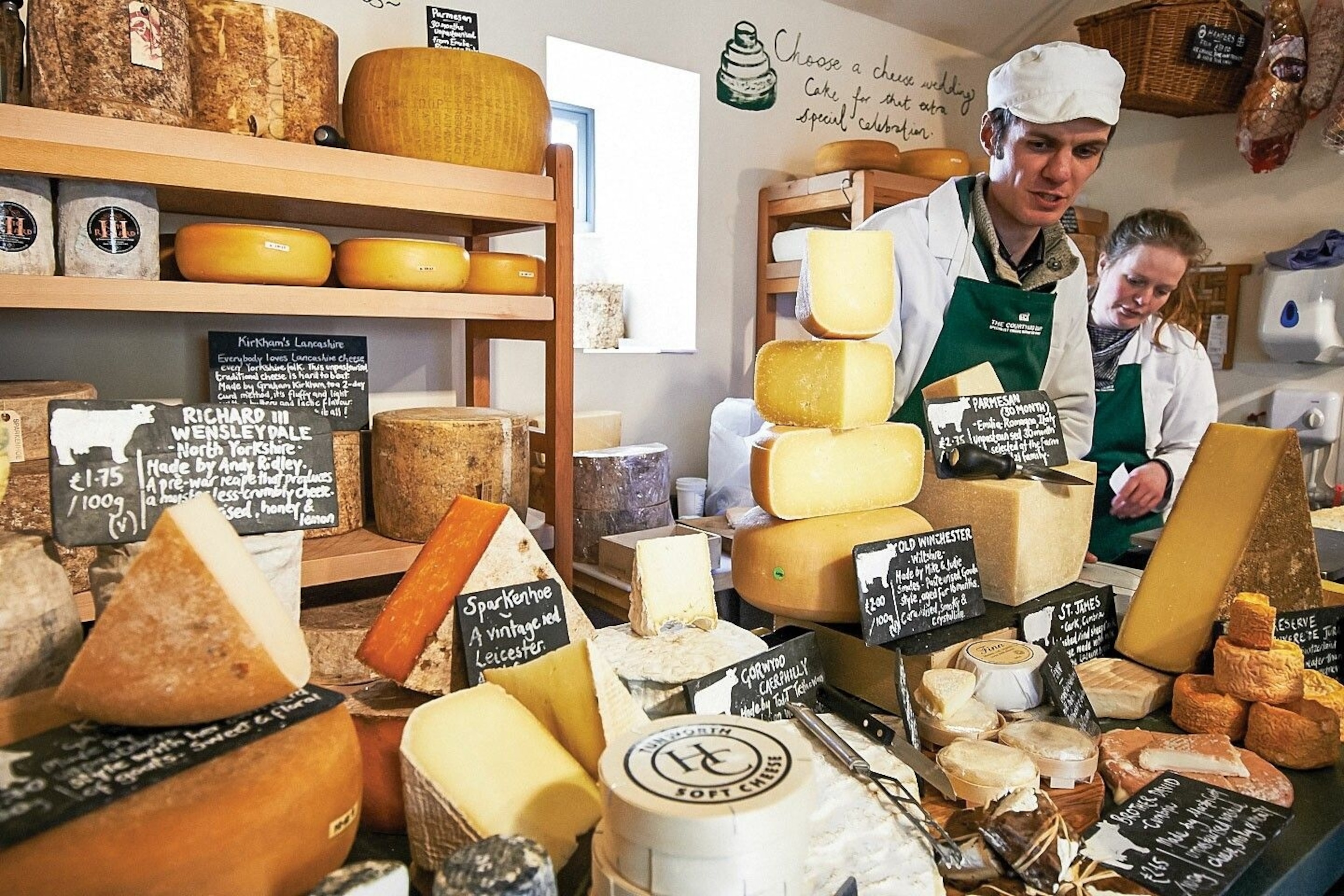

Andy Swinscoe, cheesemonger and co-owner of The Courtyard Dairy, Settle, Yorkshire

When did you become interested in cheese?

I always wanted to work with food. I went to catering college and worked at a Michelin-starred restaurant in Edinburgh that had an amazing cheeseboard. We visited Scottish cheesemaker Humphrey Errington, who’s very charismatic. Then my head chef suggested I see if I could get a job with Mons, our French cheese supplier. I was offered an apprenticeship, so I went to France for six months — without speaking any French.

What was that experience like?

I learnt a lot. I’d visit a different farmhouse cheesemaker every weekend and make cheese with them. I learnt how to care for cheese every step of the way. At Mons, they always said ‘it’s not olive oil’ — you can’t just put cheese on a shelf and forget about it. It’s a living product, so you need to look after it.

How did you get started?

My wife Kathy and I wanted to set up our own cheesemonger. We found a tiny unit in Settle and opened in 2012. We could only fit 20 cheeses in the shop, so we had to choose carefully. We selected those we knew were amazing. It was tough at first as we didn’t sell the cheeses people asked for: there was no Manchego, no Wensleydale with cranberries. We were selling British cheeses they’d never heard of. We had to convert customers through talking and tastings. But we outgrew that shop and moved to a bigger one, where we now stock 30 cheeses. Retail is where it’s at for me. I love when people come to the shop, taste a cheese they don’t know, you tell them about it and they buy it. And because of coronavirus, we’ve bought a vending machine as a way of selling quality farmhouse cheese to people who don’t want to come inside or are in a hurry.

Do you enjoy working with cheesemakers?

Yes. I only work with people I like. We visit and get to know them. Cheesemakers like Whin Yeats Dairy, Tenacres Cheese and the Hattans in Nidderdale all came to us for advice when they started. We helped them, and they now make great cheeses, which is massively rewarding. We’re proud that when we set up eight years ago, there were no farmhouse cheesemakers within 20 miles of us — now, there are four.

Tracey Colley, director, Academy of Cheese

The creation of the Academy of Cheese in 2016 marked a significant moment for the British cheese world. A not-for-profit organisation, which offers cheese-focused educational training, it was the brainchild of cheddar cheesemaker Mary Quicke, who was inspired by a training programme she encountered on a visit to the US.

Having resolved to set up something similar in the UK, Quicke held an initial meeting with industry figures to gauge interest, at which point, Tracey Colley entered the story by volunteering to be on the committee charged with setting everything up.

At the time, Colley, who’d previously run her own delicatessen in Ludlow, worked for Harvey and Brockless, a UK-based speciality food distributor. “What I instilled in my staff was that fine cheese is a beautiful, edible product, but that it also has a backstory that you could tell to excite the customers,” she says.

When it came to setting up the academy, Colley says that global organisation the Wine & Spirit Education Trust offered an invaluable structural model. “They gave us so much help and advised us to offer different levels, so that people could progress their knowledge all the way to becoming a Master of Cheese.” And, as she says, when it comes to cheese, there’s an awful lot to know. “We always joke, when we do cheese and wine nights, that for the wine people there’s only one vintage a year to learn about, whereas with artisan cheese there’s a new batch every day,” she says.

The coronavirus crisis and the ensuing lockdown in the UK hit Britain’s artisan cheesemakers hard, leaving them with huge quantities of perishable, unsold stock. In response, to try to help boost cheese sales, the Academy of Cheese launched the British Cheese Weekender event: three days of online, cheese-themed talks and tastings over a May Bank Holiday weekend. Endorsed by Prince Charles, patron of the Specialist Cheesemakers Association, and celebrity chef Jamie Oliver, the event was a success. “We were overwhelmed by the generosity of people who gave us their time to do talks,” says Colley. “It showed UK cheesemakers what the Academy of Cheese could do for them.”

While 2020 has undoubtedly been a challenging year for artisan cheese producers, Colley is upbeat about the future of the academy. “Because we do e-learning, we have a massive reach. We’re teaching now in Chinese, Japanese, Portuguese, Norwegian and there’s international interest because no one else is doing this,” she says. “People want to learn about cheese.”

Published in Issue 10 (winter 2020) of National Geographic Traveller Food

Subscribe to our newsletter and follow us on social media: