This story begins like all good ones do, with a 66-year-old man standing on stage, dressed as a goat.

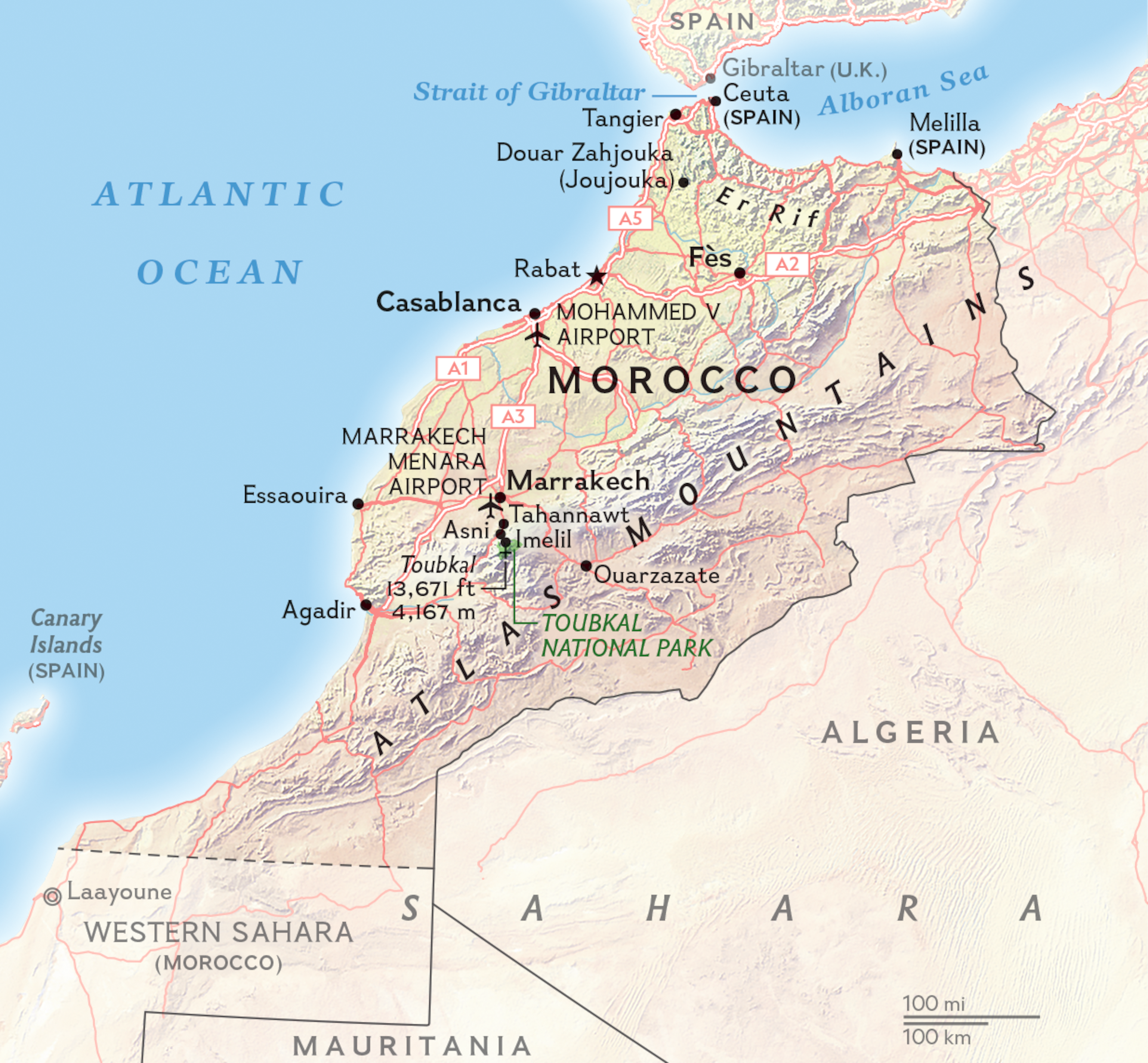

It is late March, and I’ve come to Morocco, in part, to see a rare public performance by the Master Musicians of Joujouka, a group of traditional Sufi trance artists from a remote corner south of the Rif Mountains who have nevertheless captivated the world. Brian Jones of the Rolling Stones recorded the Masters in their village in the late ’60s. William S. Burroughs and Timothy Leary famously dubbed them “the 4,000-year-old rock band.” More recently, Billy Corgan of the Smashing Pumpkins spent a week just observing them.

The Masters’ brand of ancient trance isn’t simply entertaining. It’s also said to have healing powers. The half man, half goat who is part of their act is called Bou Jeloud, and according to folklore, if he hits you with a stick during a performance, you will get pregnant. More on that soon.

The plan was to spend a week exploring Morocco through its music, which is as varied as its landscapes—from the Atlas Mountains to the red walls of Marrakech to the expansive deserts, where the sound takes on a shape and color all its own. Here, Berber drums beat in surprising rhythms, and music played on ouds, an instrument like an 11-string lute, reflects the country’s Arabic roots. Here, Gnawa music emerged from the country’s slave-trading past, carried over on slave ships from West Africa that docked in Mogador, now called Essaouira. Taken together, the music provides a soundtrack to the country’s rich and complicated history, and a creative tool to shape an itinerary.

It wasn’t my idea, exactly. Paul Bowles did it first. In 1957 the author of The Sheltering Sky asked the Library of Congress to sponsor a recording expedition across Morocco. He hoped to preserve the country’s music before foreign influence muddied the waters. (He was also maybe a colonialist who never wanted Morocco to evolve.) But his expedition proved fruitful. For four months he and his assistant hauled bulky recording equipment across more than 1,100 miles—capturing folkloric sing-alongs, sword dances, percussion on goatskin drums, and even the final call to prayer delivered in Tangier without speaker wires. (Discover the best things to do in Marrakech.)

I didn’t need reel-to-reel tape. I had an iPhone. As I’d discover over this unlikely week of travels—which included the Master Musicians of Joujouka as the surprising headliners of a hip, new electronic music festival—neither these layered musical traditions nor the young people populating today’s scene are stuck in amber. The past very much informs the present, with a new generation of artists emerging in thrilling ways. This revolution will be livestreamed.

Ahead of my trip, I had called Hatim Belyamani, a multi-instrumentalist and native Moroccan who founded Remix ⟷ Culture, a Brooklyn-based nonprofit that works to bridge global communities through music and film. One project focuses on documenting the sacred music of Innov Gnawa, a Sufi ensemble of Moroccan immigrants in New York City. Belyamani shared secrets about traveling in Morocco, some of which retained a mystical edge. Before I left, he helped set my intention: “Music is a good tool for opening our hearts and our eyes and our minds. We’re not playing into the trap of a museum format—of saying, ‘This is traditional Moroccan music and we’ll put it in a box and you’ll know everything there is to know.’ Any cultural experience is by definition alive.” I went in search of the heartbeat.

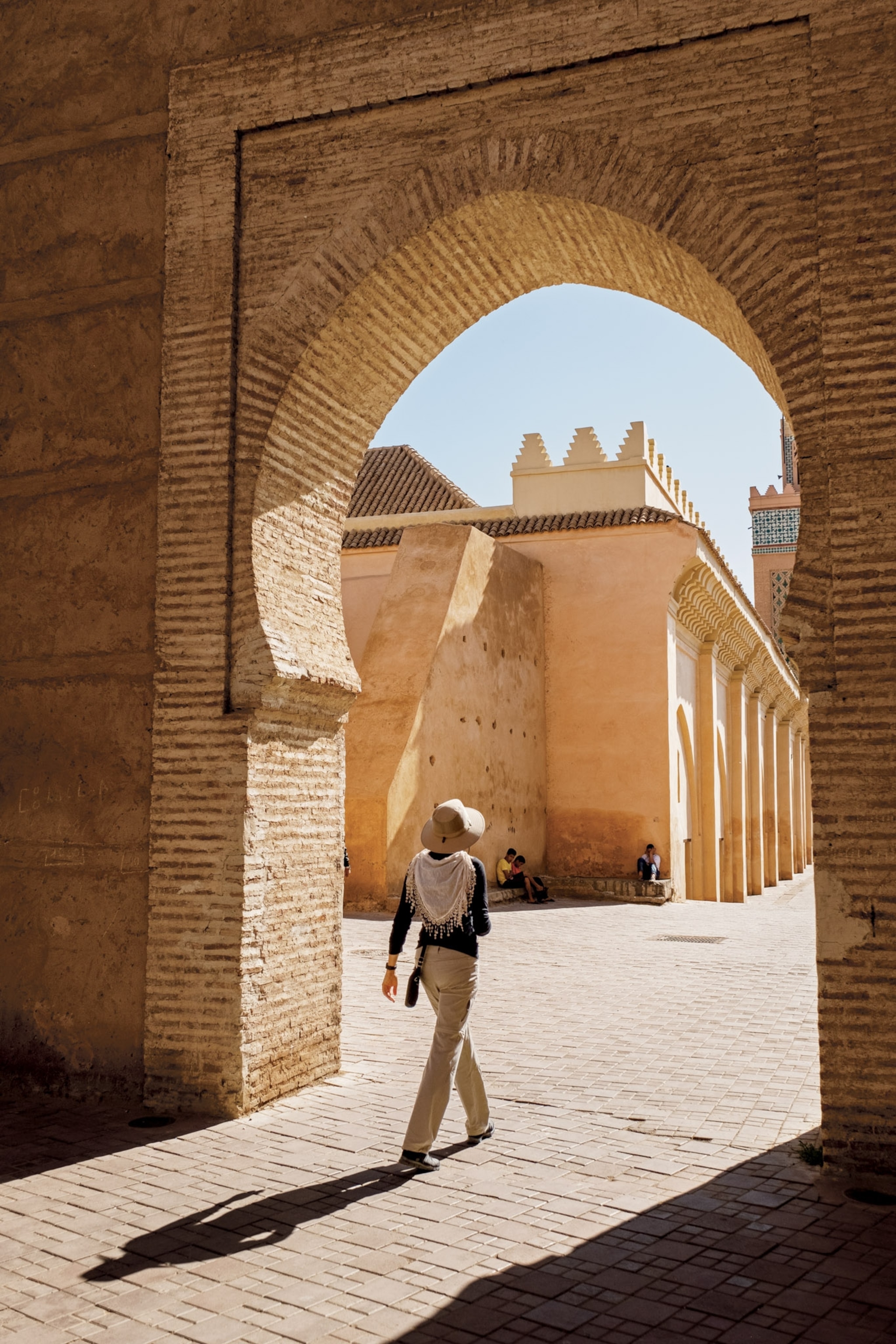

The Red City

From the moment I touch down, it’s easy to see why Bowles was captivated by the music. In Marrakech, musicians and snake charmers gather on the famous square, Djemaa el Fna, the sound of horns echoing off the walls of the old city. Scooters rip-roar through increasingly narrow streets, like its own percussion. The Islamic call to prayer—the adhan—bellows out five times a day.

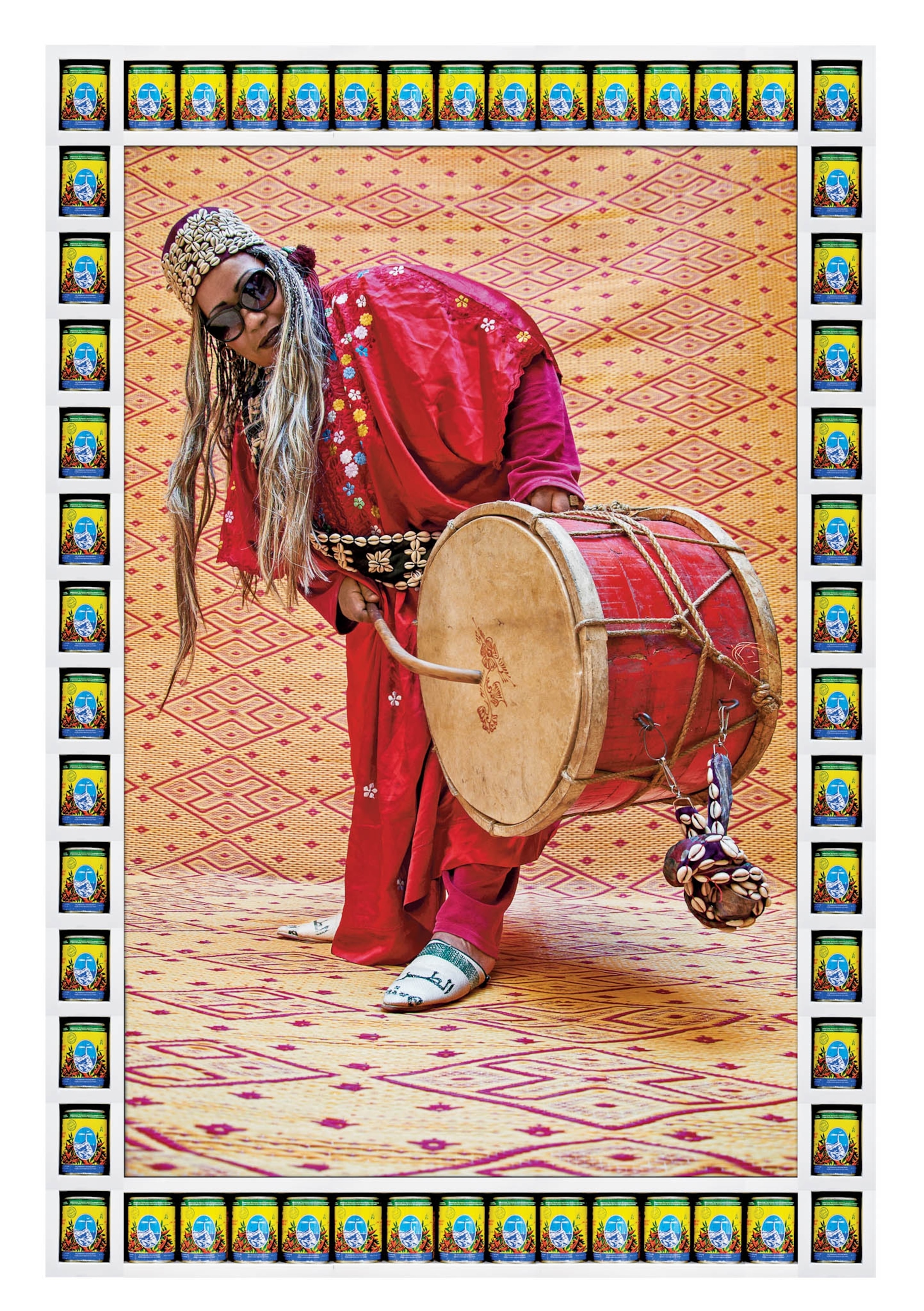

Down a twisty side street (as everything must be in the Red City), I sit for a cup of tea with a Gnawa master named Mohammed Sudani, whose official job is to keep the fires of a local hammam burning. He sits on a carpet in what feels like a cave, strumming a guembri—a hollowed-out, single piece of wood covered in camel skin and shaped like a canoe—and singing in Tamazight (the language group of the Berber people, the indigenous tribes whose traditions long predate the arrival of the Arab people in Morocco). The string of his fez spins atop his head like a ceiling fan.

Through a translator, he tells me: “The music is spiritual. The music is a doctor.” He isn’t exaggerating. The healing power of music will be a running theme. My guide explains the Gnawa ceremony of lila, which is said to force out the evil spirits, the bad jinn. A pioneering female Gnawa musician named Khadija El Warzazia will later echo this point, telling me how she once cured a Swiss man of his persistent erectile dysfunction (!) during a powerful lila that began with a goat sacrifice. She also tells me she’s clairvoyant. What does she see for my future? She smiles: “Only good things.”

Eager to take a break from the kinetic energy of Marrakech—and wanting to dig deeper into the country’s musical traditions—I ask Sarah Casewit, co-founder of the experiential travel outfit Naya Traveler, to arrange a music lesson for me at a small Berber village in the High Atlas Mountains.

The drive is stunning. These mountains begin at the Atlantic Ocean and stretch across to the Algerian border. Marrakech’s red walls quickly give way to olive tree groves and then snowcapped peaks. An hour into the journey, we stop for tea at an open-air Berber market in a town called Tahannawt. My tour guide, Mohammed—ruggedly handsome despite a very ’90s soul patch growing on his chin—came armed with jokes.

“Did you see the Berber 4X4s outside?” he says, pointing to a row of donkeys.

The market (open only on Tuesday mornings) is filled with vendors selling vegetables and juicy strawberries, which are gloriously in season. Charcoal clouds from small grills waft through the tight aisles of the market. Spice vendors lead to clothing stalls and finally to a meat-and-fish market, where you can buy a whole goat—slaughtered and cleaned—but with its hairy face still attached. Proof you’re getting what you paid for.

Mohammed haggles over the price of the tea leaves we’re about to brew. Why argue over such a small purchase? He laughs, telling me haggling makes mundane tasks exciting: “It makes it tasty.” Which is the best explanation I’ve ever heard and also an invitation for everyone to play the game with confidence. When the tea is properly steeped, Mohammed raises the kettle high in the air and shows me how to pour a cup. One should never announce that tea is ready, he says. Simply start pouring and let the bubbling sound be the siren call. There is music everywhere.

As promised, the village of Anraz (population around 600) is seriously remote. The Soul Patch and I hike through lush green hills dotted with white cherry blossoms, walking past a dozen sheep out for a leisurely stroll. Finally we arrive at a rustic hilltop village of adobe huts and low doorways. At first glance, little appears to have changed in decades. Or so I think. Until the local kids greet me as modern kids do everywhere: by staring down, their faces glued to the glowing screens of their smartphones.

I’d read up on Berber history at the tour operator’s behest. Sarah had grown up in Morocco, and she’d told me there was a movement away from the term “Berber,” which had been thrust upon the tribes by the Romans, taken from the word “barbarian.” The locals preferred to be called Amazigh, or “free people.” And their music has been one of the most prominent ways of maintaining their identity. (A must-see museum of Amazigh history is housed in the Jardin Majorelle in Marrakech; elsewhere, the Royal Institute of Amazigh Culture launched in 2001, aiming to bring the Tamazight language and music to public schools.)

There is more tea awaiting—with mountains of white sugar cubes—as four men dressed in flowing jellabas and four women in head scarves and lace skirts prepare to perform. One of the men is warming the skin of his drum over an open fire; the goatskin can get tight in the cold, and the sound resonates better with a little heat. I ask what the songs are about. The drummer shrugs, then says, “Love and history.” What else is there to sing about?

The ritual music—which is usually performed at weddings and at important life events or simply around the house—rings out in a gleeful call-and-response. Sometimes the women hold hands; other times they shimmy and laugh. Seated on the floor, my guide whispers that this particular song is about masculinity—about striving to be an “eagle that crosses the ocean” and not “a falcon that merely crosses a river.” We should all be eagles, he says. Which is the opposite of how I feel when the men pull me into the circle, dress me in a jellaba, and hand me a drum. While the rhythm eludes me, the joy does not.

That evening, I check into Kasbah du Toubkal, an Amazigh retreat some 6,000 feet above sea level, on the edge of Toubkal National Park, in the small town of Imlil. There is no road up to the front door. A driver drops me off in town, where a donkey takes my luggage on a 15-minute trek to the hotel’s gate.

It is seriously cold that night, and it pours a near-biblical flood. I am startled by a sudden knock at the door. My host has brought me a hot water bottle to warm the bed, which, I can attest, is truly one of life’s great lo-fi pleasures. In bed I wonder if I am an eagle flying over rivers or a falcon pretending to be a man—before letting the tap-tap-tap of the rain lull me to sleep.

Moroccan melodies

I return to Marrakech just in time to see the Master Musicians of Joujouka perform at the Beat Hotel festival, held on the grounds of a chic 27-acre boutique hotel outside of town. In addition to the Masters, the lineup includes upstart DJs from Casablanca, pop-up restaurants, and a spa tent offering yoga. The transition is jarring. British party kids with sunburned skin and vape pens sit around a pool. The Wi-Fi password is MOONLIGHT. This isn’t what Burroughs or the Beat poets imagined. But it is a bold mash-up of genres and experiences come to life.

The Masters—who range in age from late 40s to 86—take the stage after ten o’clock, under a white tent with a top-tier sound system and a serious light rig. The 13 men are dressed in jellabas. They carry drums and reed instruments and sit in a single row of chairs facing the crowd. The music is visceral, the high-pitch whir of the lira flutes like a snake worming its way through my earholes and taking hold of my brain stem. Historically, this brand of Sufi trance had been used to entertain the court of the sultan. It was also performed to inspire soldiers prior to battle. Which makes sense. It is that loud from the first drumbeat.

The Masters play nonstop for two hours, with more energy than men half their age. An hour into the show, Bou Jeloud—the half man, half goat—finally appears. The man under all that goatskin is called Mohamed El Hatmi. He’s 66 years old, and he’s been dressing up as this furry icon for more than 35 years. He measures a hair under five feet tall. But he is superhuman, climbing down into the crowd and running back and forth among the people, shaking his sticks in the air.

We’re in the presence of great power, a friend whispers. “People that have mental problems or feel possessed by some affliction come to the village of Joujouka,” he says, adding: “Close your eyes.” I don’t get pregnant. But I am changed.

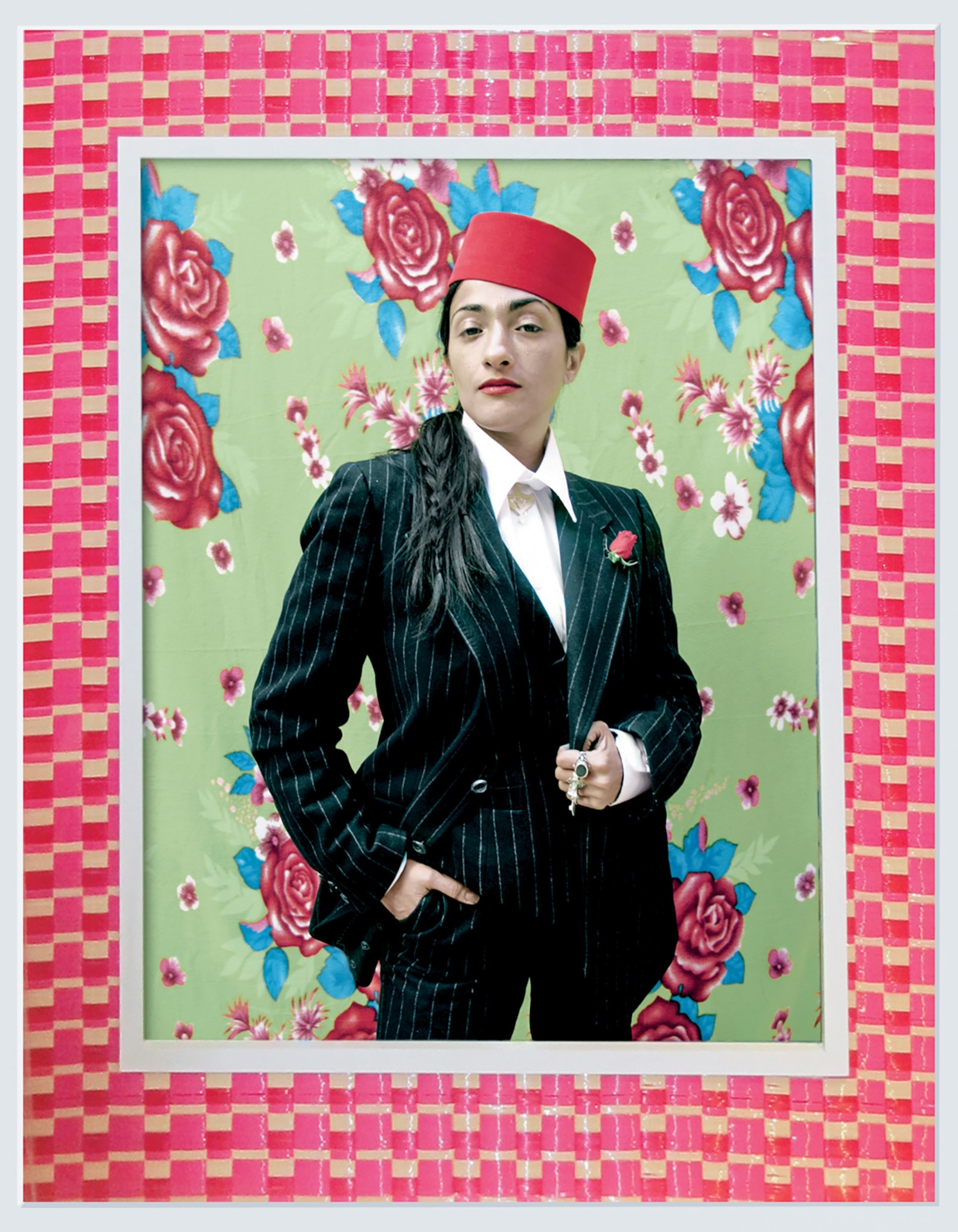

When Brian Jones recorded the Master Musicians of Joujouka 51 years ago, it basically launched the category we call “world music.” But there’s a vibrant, creative class on display at the Beat Hotel and elsewhere in Morocco—a new generation of artists challenging cultural norms and carving out their own landscape. Maalem Houssam Guinia, son of the late Gnawa legend Maalem Mahmoud Guinia, performs at the festival with the celebrated British DJ James Holden. The bill also includes two young DJs, Kosh and Driss Bennis. Driss is the founder of electronic label Casa Voyager, named for a train station in their native Casablanca. But their major influence, they tell me, wasn’t Berber folkloric music but rather the Detroit electronic and techno scene.

Driss admits this has sometimes been a problem for them from a marketing standpoint. The press, he says, always wants there to be some hipster Gnawa backstory to their journey. “The cliché of the local Africans that play ethnic and fusion music,” Driss says. “But that’s not what we do.”

“I didn’t have Gnawa music on my iPod growing up,” says Kosh. “When I was a teenager, it was Iron Maiden, Metallica.” This is part of the reason Driss started Casa Voyager.

“The label is a way of documenting a moment,” Driss says. “We are here in Morocco. In Casablanca. In 2019. Making records. We want to break this colonial dynamic.” Translation: Thank you, Paul Bowles, but we’ll take the mic now.

I feel as if I am witnessing a revolution or perhaps an emancipation from expectation. The very existence of this festival—and others like it in Morocco—is proof that this generation is already seizing the throne. Early in the trip, I was introduced to two hip Moroccan cats, Reda Kadmiri and Karim Mrabti, who are consultants for the Beat Hotel, after Karim founded his own groundbreaking festival, Atlas Electronic, four years earlier. (Unearth Morocco’s treasures in its labyrinth of souks.)

Reda grew up partially in Montreal; Karim was raised in Rotterdam. It was that outsider mentality that partly inspired Karim to get Atlas Electronic off the ground. Dressed in an orange sweatshirt, black jeans, thin gold chain, and Adidas sneakers, Karim recalled the uphill battle they’d faced. Was it safe? Would people come? But he’d pushed back, saying, “If there can be a wedding of 500 people in Morocco, there can also be a festival.” Or a dozen of them.

Reda is standing next to me while the Master Musicians of Joujouka play. He’s traveled to Joujouka four times to stay with the Masters. And he greets them with arms wide open. Reda had returned to his native Morocco with a purpose, and the music he championed has a healing power all its own. “Culturally,” he says, “Morocco has been through many changes in the 63 years since independence. But today we see a generation of young Moroccans torn between two different appeals: one of conservatism and one of progressive emancipation. And those two currents are very strong. There are times in history where the balance could go [either] way. And it just seems the cause is so close and every hand is important on deck right now.”

Looking around, he says: “There are beautiful examples of the diaspora coming back home—finding their space, their community, and their role.”

What happens next? Not even a clairvoyant like Khadija could know that. I ask Frank Rynne, who manages the Master Musicians of Joujouka, about the future of the band. Would their children take over? Frank is optimistic—although he acknowledges the issue has been exacerbated by the arrival of cell phone service in their remote village. “The kids in Joujouka love the music, but they’re drawn to the bright lights, big city. You’ve got kids from Joujouka throwing gang signs on Facebook.”

The cultural tectonic plates are shifting in thrilling ways. Still, the single best show I see all week is at Café Clock in Marrakech, where four women perform traditional music at deafening volume while young people dance like nobody is watching. Except someone is watching. Because they’re all filming themselves with their iPhones.

Inspiration by the sea

Before I leave town, I take a day trip to Essaouira—a port city on the Atlantic Ocean where Jimi Hendrix, Cat Stevens, and Frank Zappa all famously traveled for inspiration. Essaouira is a three-hour drive from Marrakech, and it’s home to a four-day Gnawa festival held every summer. My driver plays traditional folkloric music the entire way, telling me the metal of the castanets is meant to recall the sounds of the chains the slaves wore. Months later, I will struggle to get the clang-clang-clang out of my head.

The seaside city emerges from the mist like a dream. Or like an oil painting of 18th-century fortifications protecting a sacred port. According to legend, Hendrix wrote “Castles Made of Sand” about Essaouira. It’s a good story. But the song was actually released two years before Hendrix’s first known visit. Still, I could see why the story lingers. The joint is that beautiful. Essaouira is like Marrakech’s polar opposite, or a palate cleanser anyway: a beach town where children kick around a sand-covered soccer ball while their parents take in the sun. The place is still inspiring global artists. HBO’s Game of Thrones came here to film a season-three scene featuring the Mother of Dragons, Daenerys Targaryen.

In the old medina, tight rows of vendors sell meat and spices and carpets. Photos of Hendrix still hang in shop windows. I head to Taros Café, a rooftop escape with glimmering ocean views. I’d heard that musicians sometimes perform out on the deck, although apparently that’s only at night. It is lunchtime, and I am starving. So I sit anyway and stare out at the azure ocean, ordering a baked white fish and a glass of cheap white wine. I hear music from the town square below, where tourists clap for local musicians, throwing coins into guitar cases.

I find myself thinking about a conversation I’d had with a DJ who lives in Casablanca called Kali G, who often samples Moroccan folkloric music—Berber voices, Gnawa instruments like the flute that announces the start of Ramadan—into his dance tracks. I’d asked him about Sufi trance and about healing. How does it work? And could I take it home with me? He smiled, then said, “First you have to get rid of your material possessions. Then ego. Only when you say goodbye to fear do you open the door to something beautiful.” He was right.

Sitting here on the rooftop, I am listening to a different type of music: the sound of the alizé, Essaouira’s famous coastal winds. Taros, the name of the restaurant, is actually the Berber word for “coastal wind.” The waves lap up on the shore below, rushing in, rushing out. There’s no need to rush at all.