Climbing ‘Fire Mountain’

High hopes amid high temperatures fuel a hunt for ancient rock art in Namibia.

Brandberg mountain is burning.

A remorseless globe of sun is scalding the sky. Rocks scattered on the mountain are too hot to touch. Shade is the only shield from oppression.

I’m three hours into climbing Namibia’s remote Brandberg mountain with my guides, Angula Shipahu and his 24-year-old son, Thomas—and the gorge we’re ascending, the Ga’aseb, on the south side of this solid monolith of granite, is a steep, treeless avenue of boulders. Finally we stop to rest in the shadow of a house-size rock, shrug off our heavy packs, and collapse. It’s too hot to talk. We just lie on our backs, close our eyes, and guzzle water.

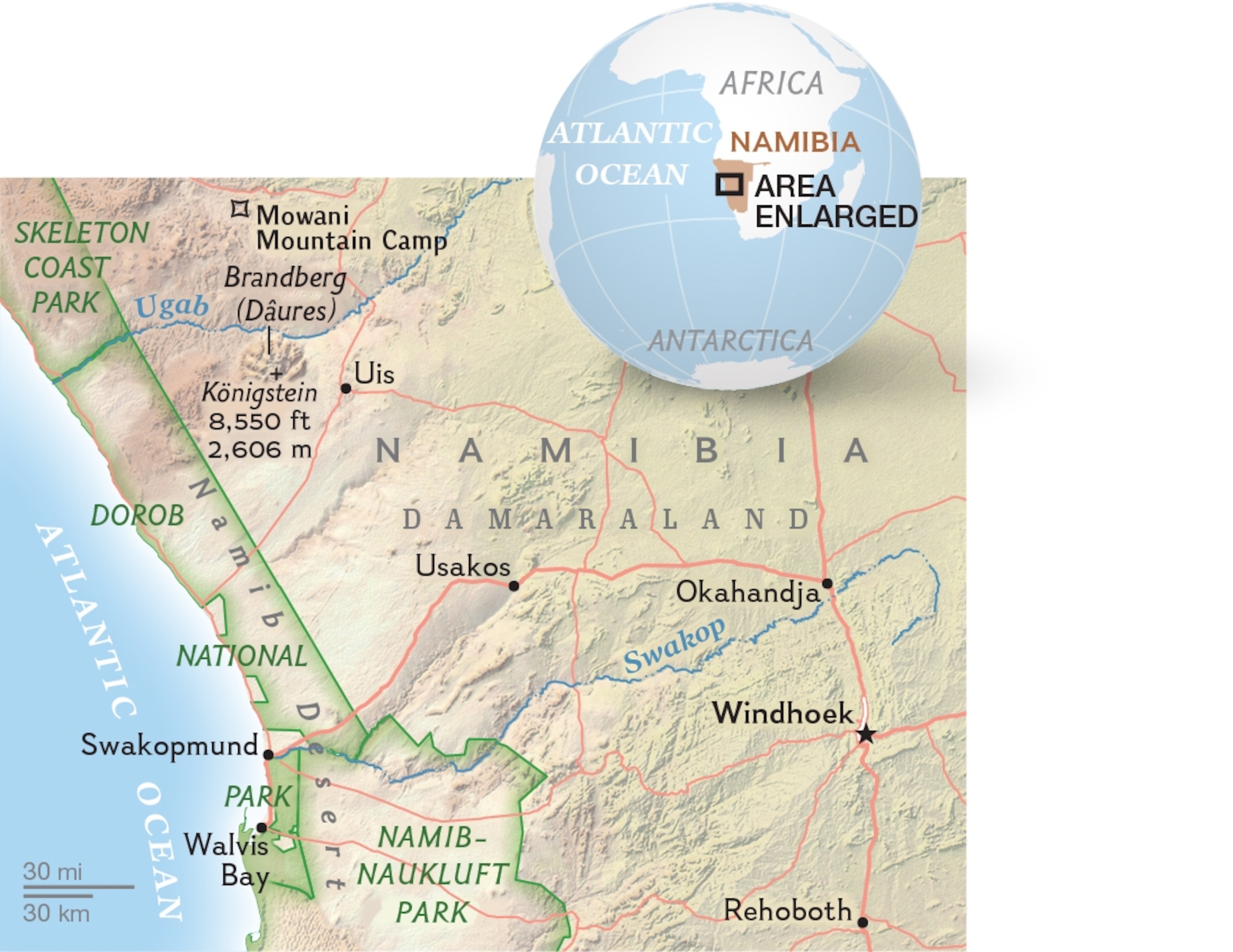

Brandberg means “fire mountain” in German and the local Afrikaans, a literal translation of the tribal Damara name, Dâures. The appellation wasn’t inspired by the scorching temperatures but by the glowing scarlet color of the massif first at sunrise, then at sunset. Geologically, the almost perfectly circular formation some 20 miles in diameter is one of the most unusual mountains on Earth, a product of the splitting of the ancient continent of Gondwana into the southern continents we know today. As the rift caused by South America’s separation from Africa widened, it produced isolated intrusions of rock, including today’s granitic Brandberg massif, which rises above the surrounding desert and is crowned by Namibia’s highest point, the 8,550-foot-high Königstein (“king’s stone”).

I think we’ve stopped here because it’s the largest patch of shade Angula can find. But when I raise my salt-stung eyelids, I spot a painting on the rock wall above us. An arrow of excitement pierces me. This is why I’ve come so far: Brandberg’s ancient rock paintings. I stand to study the ancient artwork. Two tall, naked men chase a bounding springbok. The lead runner appears to have tossed behind him his bow and quiver of arrows, which the second runner is about to catch in midair, and is reaching out for the springbok’s tail. All three figures are finely drawn in red ocher on a canyon wall of russet-colored granite. The image is so simple and yet so dramatically descriptive. Here is the elemental survival story of all early humans: the hunt.

Angula, a man with an inscrutable face that transforms briefly when he smiles, is pleased to see how the picture captivates me. He instructs his son (Angula doesn’t speak English) to inform me that an even better painting waits close by, if I’m willing to hike some more. I consider. My two guides are lean, muscled men who blithely walk vast distances in insufferable heat. Still, I’m game.

We leave our packs and zigzag up the slanting wall of the canyon. I follow directly behind Angula, who, at 61, remains agile and sure-footed. We surmount rock shelves perched on delicate ribs of stone, our boots angled on the sloping surface, then cut back beneath a low overhang. Angula gets down on his hands and knees and crawls into a cave. I follow. Inside he points up. On a concave wall just a few feet from my face, I make out a rock painting. Three human figures wearing headdresses as well as bracelets are approaching a white giraffe that wears an ornamented crown. Each figure’s torso is decorated, one striped, one splotched with white, one—perhaps a female—with what looks like a snake in her belly. The giraffe appears to stand under a shower of rain. I theorize that the men are honoring the giraffe and celebrating the rain. Which makes complete sense. Lying in the cave, the sun and searing heat just a few feet away, I easily can imagine a hunter hiding out here, deeply in need of rain and game and attentively painting this scene.

I HAD BEEN TOLD DECEMBER was the wrong time to travel around northern Namibia.

“You do know it’s summer here,” an in-country contact had informed me by phone as I sat in my office in Laramie, Wyoming. “It can be extremely dry; temperatures reach 50 degrees.” That’s Celsius. Equivalent to 122 degrees Fahrenheit. Gazing out my window at a winter-white landscape, which just that morning I’d cross-country skied along, I couldn’t fathom that sort of heat.

The weather that greets me when I arrive in Namibia’s capital, Windhoek, is pleasant—temperately warm and a bit rainy. It won’t last. A five-hour drive north the following day to the edge of the Namib Desert (the last 75 miles on dirt road) brings me to the isolated outpost of Uis. I’m in the middle of Damaraland, a region of rocky hills, gorges, and expanses of sand where a number of tribes—including the Damara, the Himba, and the Ovambo—eke out a scrappy living in the desert scrub. The air conditioning has been blasting the entire drive, so when I open the car door and step out, it feels like opening an oven and stepping in.

Determined to not let the temperature discomfit me, I walk briskly into the Brandberg Rest Camp, a sort of motel with camping options, and ask for proprietor Basil Calitz.

Calitz and I had corresponded by email; he was the only person of some two dozen I’d contacted who’d said visiting the Brandberg was possible this time of year. Insane, maybe, but possible. He’d set me up with the man who discovered many of the paintings, Ovambo legend Angula Shipahu.

“Mr. Calitz is off property,” says one of his staff, “but will be here later.”

I hang out at the rest camp’s pool for the remainder of the day, trying to acclimate. At dusk Calitz roars up on a rugged dirt bike. He is a massive man, with a big beard, big belly, and big voice. Wearing articulated black leathers dusted in desert talc, his giant helmet under his arm, he resembles some sort of Visigoth.

He claps me on the back, shakes my hand up and down vigorously, and calls for two pints.

“So you found Uis,” he booms. “What do you think of it?”

“Reminds me of a ghost town in the Arizona desert,” I reply.

Calitz, whose beard and hair are so long and intertwined that it’s hard to tell where one begins and the other ends, quaffs his stein of beer, wipes his mustache, orders another stein, and gives me his personal history of Uis.

Founded in 1960 by a South African firm, Uis began as a tin-mining company town, Calitz explains. Tiny brick homes were built on the east side for the black miners and more spacious accommodations on the west side for the white administrators. During apartheid, South Africa couldn’t buy tin on the world market because of international sanctions, so it mined it here, at a loss. Some 85,000 tons of rock would be gouged out of deep strip mines, according to Calitz, and processed to produce just 1.4 tons of tin. In 1990, about the time apartheid—and its UN-imposed sanctions—ended, the mine was closed, leaving hundreds of native workers without jobs. Though they had homes here, Calitz says, the absence of employment drove many back to goat herding and occasional poaching. Seven years later a Namibian businessman bought the mine, its equipment, and the abandoned white side of town and began advertising Uis in Europe as a vacation community.

“Germans, Austrians, French, Swiss, Italians, they could buy a vacation home here for 3,000 euros,” explains Calitz, lighting another cigarette. “They only come for three months a year.”

“Do you even have winter?” I ask, using my sleeve to towel the sweat off my face.

“Of course,” he bellows. “It came on a Tuesday last year.”

A third-generation Namibian and jubilant bachelor who has worked as a photographer and a roof thatcher, Calitz, 56, bought the dilapidated Brandberg Rest Camp—which originally was Uis’s recreation center, with a pool and indoor badminton courts—with a few partners in 1995.

“The place just touched my heart,” he says. “I knew this was where I wanted to spend the rest of my life.”

The following morning he gives me a bouncy tour of the town and its residents in his Land Cruiser. We pass the strip mine— now a reservoir of green water where a retired electrical engineer has started a tilapia fish farm—and the local hardware store, operated by a former harbor captain whose tools sit dry-docked. I meet a grizzled, chain-smoking prospector named Lorri who still searches for the El Dorado of amethysts and plays blues guitar; and Louis Geldenhuys, who was a member of the first team of Namibians to relocate endangered black rhinos—and to cut off a rhino’s horn to protect it from poachers.

Extreme places attract unusual people.

“This town is a magnet for the weird and wonderful,” Calitz exclaims.

BECAUSE OF THE HEAT on Brandberg’s rocky surface, Angula, Thomas, and I hike only for half-hour stretches before taking shelter beneath available boulders. Even they admit it’s hot. Adding to our challenge is the weight of our packs. The Brandberg has experienced drought conditions, and Angula hadn’t been sure we’d find water. So we each carry 12 quarts—the equivalent of 25 pounds—along with our camping supplies for a week.

Reaching 6,000 feet, we stumble onto the vast granite openness of a plateau-like area. We’re surrounded by miles of undulating rock and rounded boulders. It’s so hot that the granite itself, red in the angling sun, appears burnt—a devil’s desert of stone.

The heat begins to abate with the approach of dusk. We search for water in surrounding potholes, known locally as the Longi Pools. One after another is bone dry, ringed only with salt. Angula looks concerned. If we don’t find water, we’ll be forced to head back down tomorrow.

We walk to the end of a granite spillway and come upon a solitary pothole. Ten feet down it I spy a foot of rainwater filled with moss and minnows. The stuff looks nasty, but it’s water. We tie a line to my cup, drop it into the hole, fill it, pull it back up, and pump the green liquid through a filter into our plastic jugs.

That night a breeze kicks in and carries the heat away. The rocks around us are almost luminescent beneath a southern sky crowded with stars. We hear the deep humphing sound of a leopard breathing. We make a campfire, around which I learn about Angula’s life.

For eight years, from 1977 to 1985, Angula lived on the Brandberg, descending only every few months for supplies. He had been hired to find rock paintings by an Austrian artist named Harald Pager, who migrated to South Africa after World War II and would spend two years photographing rock art in that nation’s Drakensberg, or “dragon mountains.” At the time much of Brandberg’s rock art was undiscovered. To find new works, Pager engaged locals, including Angula, who had never even been on the mountain. Pager paid them for each artwork they discovered—less than the tin mine paid, but Angula realized he had a talent for finding paintings. Even during the searing heat of summer, he would crawl into every cave and peer under every boulder in search of the art of a vanished tribe.

“When I found a rock painting,” Angula said (with Thomas translating), “Pager was pleased.”

Weathering had faded many of the artworks, so rather than photograph them, Pager traced them on paper. It proved to be painstakingly slow work, but, Angula says, Pager was obsessed.

“He would trace from six in the morning until three the following morning, sleep for three hours, then resume tracing. He hardly ate, and drank only a half quart of water a day.” Pager’s appetite, Angula adds, was for cigarettes and coffee.

After some eight years on his knees tracing images, Pager died in 1985. Astonishingly he had recorded some 40,000 drawings at almost a thousand sites, filling more than four miles’ worth of tracing paper. These are now collected in a six-volume set published by Germany’s University of Cologne, each tome the size and thickness of an atlas. Because of Pager and his band of local art hunters, Brandberg mountain is recognized as the home of one of the largest collections of rock art in the world. The entire mountain is an alfresco art gallery.

WE GET GOING BEFORE DAWN the next morning, scrambling between boulders while the air still is cool. This is the only time I can recall ever dreading sunrise. We hike swiftly, covering as much ground as possible before heat blankets the landscape. Angula has hiked this trail hundreds of times; he could walk it with his eyes closed. Along the way we spot distinctive piles of leopard and hyena scat.

Angula is guiding me to the site of one of the finest works of aboriginal rock art anywhere: the Snake Rock cave. Its entrance isn’t immediately obvious—if you didn’t know it was there, you’d walk right by it. We duck our heads and slip inside. I’m expecting a few paintings. What I see shocks me—a wide panel of giraffes, elephants, snakes, kudu, springbok, hartebeests, zebras, and humans.

According to an expert on Brandberg’s art, German archaeologist Tilman Lenssen-Erz, the images range from 2,000 to 4,000 years old, painted by hunter-gatherers who likely were ancestors of the present-day Bushmen, or San people. White tints may have been made with ostrich eggshells, yellow with yellow ocher, black with charcoal and manganese ore. Red paint was crafted from red ocher mixed, perhaps, with animal blood. The thinnest lines may have been drawn with tiny bird bones, thicker lines with feathers, and brushstrokes with animal fur. Humans and big game animals are the primary motifs.

I make out slender human figures who are striding or leaping, praising or praying. Lenssen-Erz has noted that the depictions “focus on community, equality, and mobility, propagating the ideal of a person without rank, status, age, or sex.” Men, who bear bows, arrows, and other implements, are connected to the material world; women are associated with communication and communal ceremonies.

The paintings were integral to the lives of hunter-gatherers, central to their religious rites, healing ceremonies, and social interactions. Since Bushmen had no written language, their pictographs represent their deep knowledge and awareness of their environment and presumably offered one way to pass that wisdom to future generations.

I study the Snake Rock panel for more than an hour. It’s a hallucinatory palimpsest of images: animals overlapping humans, humans crossing through the ghostly bodies of animals. The exquisite anatomical accuracy with which the animals are drawn astonishes me, from the protruding shoulders of a giraffe to the clean stripes on a zebra’s nose, reflecting a highly developed sense of aesthetics. All these beasts lived on the plain far below; the painters had to hike up with the exact images in their minds. These people clearly understood—and cherished—their world.

ANGULA WILL LEAD ME to more rock art sites on Brandberg, including an obscure painting he hasn’t visited in 32 years. I wonder how he will find it in what to me seems an undifferentiated landscape. What Angula does floors me: He navigates by recognizing individual boulders from tens of thousands of lookalikes, by remembering the aspect of the slope and the position of the sun, and by recalling how long it took to walk how far. Like the ancient painters, he has memorized the Brandberg’s geomorphology.

Angula walks so smoothly, he appears to glide over the rock, conserving every drop of energy. He weaves left, right, finding the line of least resistance and never lifting his foot higher than necessary. I step where he steps, trying to mimic his ethereal efficiency. Without a stumble he leads me to the painting of an archer in pursuit.

We visit half a dozen additional sites, with paintings that have been viewed only a handful of times in millennia: groups of animals, a line of six dancing men, an ibex with enormous curled horns, three men with loopy legs, as if they’re being blown by the wind. With no water source visible anywhere, we return to our camp every night.

The evening before we hike out, we decide we must leave some water at our campsite for the next visitor. Once again we tie my cup to a string, carefully lower it into the hole, and draw up the liquid of life.

Drought may have contributed to the Bushmen’s departure from the Brandberg some thousand years ago. The rains they depict in their paintings, soaking the giraffes and elephants, vanished. The climate changed, becoming hotter and more dry. Water holes evaporated, causing game animals to migrate.

It must have been apocalyptic for the Bushmen. They appear to have abandoned their Dâures homeland, forever forsaking their paintings—today invaluable visual scriptures of an ancient culture and vanished era.

Writer and climber MARK JENKINS is the author of the 2007 book A Man’s Life: Dispatches From Dangerous Places. Photographer MATT MOYER has traveled to Iraq, the Sinai Peninsula, and Saratoga, New York, for National Geographic.