Finding balance on a nature pilgrimage with Japan's Yamabushi mountain priests

Japan’s Yamabushi priests offer visitors nature immersion and a unique insight into their culture on the slopes of the holy Dewa Sanzan.

In Yamabushi lore, the steps at the entrance to Haguro’s mountain sanctuary symbolise the descent into hell. But hell is the last thing on my mind as I stand at the carved wooden gate of Zuishinmon, with those steps before me. Japanese nightingales and bush warblers are calling to one another in the crowns of maple trees above my head. Sunbeams caress my back as I bow beneath the gate — an acknowledgement of the guardian spirits who are believed to roam these sacred slopes.

“Use your whole body to pull in the spiritual energy of this place,” says my guide Kazuhiro Hayasaka before we start to descend, single file, down the steps. We’re carrying 6ft wooden walking staffs that thud on stone like a soporific heartbeat as we hike. Frogs gurgle like drains, hidden in water channels that trickle at our feet. The air is cool and still, thanks to a blanket of cover thrown by a grand avenue of cedars, planted in the 1600s to line the 2,446 steps that steer pilgrims to Mount Haguro’s peak. If this is hell, I’m seriously conflicted.

At 414 metres high, it’s a tiny mountain by most standards. Yet almost all Japanese people intend to make this easygoing day-hike pilgrimage at least once in their lives. Mount Haguro is one of the three holy mountains of Dewa Sanzan, some 300 miles north of Tokyo in Yamagata prefecture. Its caretakers — the Yamabushi — are a unique sect of mountain priests, who have spent several years developing bite-sized training programmes to give outsiders like me an insight into their lives and belief systems. My guide on this hike up the mountain, Hayasaka, is the priest who has been assigned as my sendatsu (master).

Yamabushi sit outside the usual confines of religion in Japan. They subscribe to elements of Shintoism, Buddhism and Taoism, but primarily worship nature. It’s a practice known as shugendo, which involves meditating in sun-dappled forests, by murmuring rivers and under gushing waterfalls. A thousand years ago, the Yamabushi lived hermit-like on Haguro itself, but these days most conduct totally ordinary lives, returning sporadically to the three mountains that make up Dewa Sanzan to purify themselves. They say that a pilgrimage to the summit of Haguro represents a spiritual renewal. The topography of the mountain valley we’re in is an important physical manifestation of the Yamabushi journey. Reaching the bottom of the first set of stone steps, I spy another equally steep staircase across a traditional Japanese wooden bridge fording a river. “We overcome hell to be reborn at the top,” says Hayasaka, following my gaze upwards — the stepped path disappears skywards into thickets of ferns flanked by tiny shrines mounted on plinths.

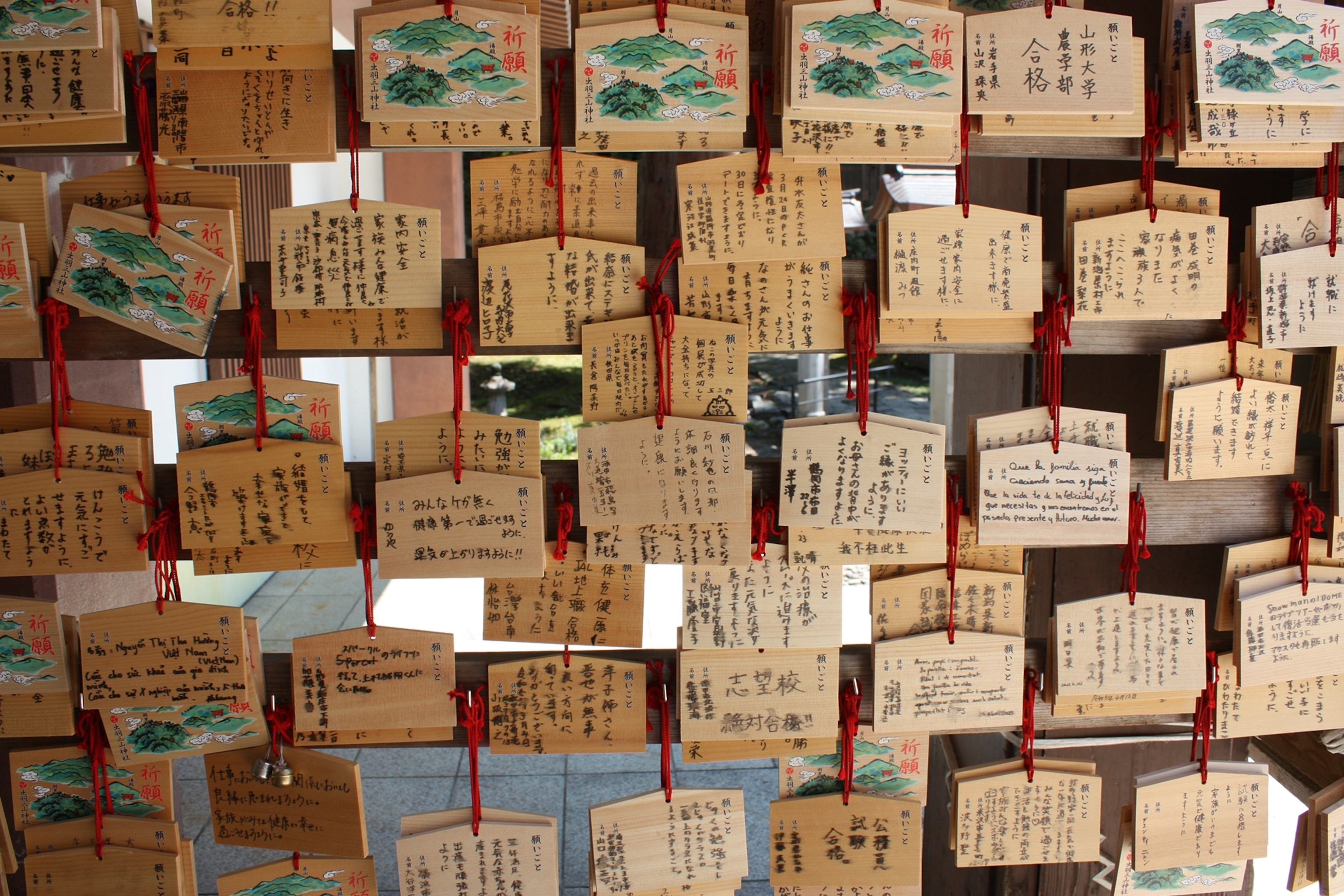

Master Hayasaka is a gentle, affable bloke who defies my expectations of any sort of priest. As is the custom for Yamabushi when in the mountains, he’s dressed head to toe in white. He wears boots with a split toe, like the shoes traditionally worn by pilgrims, and a twisted cotton cap with trailing flaps I’m told represent an umbilical cord connection to the ‘womb’ of the mountain. A giant conch horn hangs around his neck on a rope. Before leaving the valley floor, we conduct a ritual of bowing, clapping and singing sutras (religious scriptures) at Haguro’s five-storey pagoda. There are around 110 cedar-wood shrines on the slopes of Haguro, but the pagoda is one of the Yamabushi’s greatest treasures — a fitting segue to our climb. Because of the mountain priests’ focus on nature, their prayers centre on health, the balance of natural ecosystems, natural disasters and world peace.

I’m fully on board with this activity in theory, but as a life-long atheist I initially find myself flummoxed by the practice of praying — especially out loud. My tongue stumbles over the undulating rhythms and unfamiliar words derived from Sanskrit, printed out for me to carry with me for the duration of my time with the Yamabushi. My words falter even more when I realise that Hayasaka and I are being watched and photographed by a couple of Japanese tourists. With my white gyoi (training shirt), our rope shime necklaces — worn to protect against evil spirits on the mountain — and Hayasaka’s conch horn, it dawns on me that the Yamabushi and I are as much of a tourist attraction as the mountain itself. It’s an uncomfortable moment.

Beyond the pagoda lies the first of three slopes leading to the top of Mount Haguro, linked by three sets of steps and plateau pathways. Halfway up the first slope, my ears pop. Nature’s pitch changes, too. As we climb higher, the chewy humidity of the valley floor thins out, bringing a crisper breeze and warm folds of sunlight. Halfway up the second slope we veer off the steps onto a plateau marked by a red torii gate — a traditional symbolic structure — and Hayasaka announces this is a good place to mediate. We sit on small, round cushions pulled from a backpack. “Yamabushi meditation is different to Buddhist meditation,” he instructs. “It’s not about how you sit or position your hands. The main objective is to be present in nature.”

At first, I find it impossible to concentrate. I fiddle with the plant leaves that are tickling my legs, and slap away what I’m convinced is a mosquito. But eventually I find myself uncoiling. It’s like turning up a TV’s colour saturation. Sounds are richer. The fluttering of leaves becomes a roar. The rustle of insects is more defined — almost as if I could hear the air being sliced by the flap of a butterfly wing. Eventually, a woodpecker breaks the spell and we start to stir, picking ourselves up ready to tackle the final slope.

Sensory moments

The blow of a Yamabushi horagai conch horn is like nothing I’ve heard before: baritone, almost mournful, like a long exhalation of wind parting the trees. It’s the sound that Hayasaka draws forth from his conch to announce our arrival at Saikan Lodge, the shukubo (pilgrim lodge) below the mountain summit where I’m due to sleep that night. The hostel’s carved wooden pagoda doorway, nibbled by the elements over more than three centuries, is one of the last remaining clues that it started life as a Buddhist temple.

Before the Meiji Restoration in the 1860s, when Buddhism was briefly exiled and Japan made Shinto its national religion, this mountainside would have been covered in more than 30 similar temples. This is the only one that survived on the slopes below the summit shrine. Today, the lodge is highly regarded for its elevated expression of shojin ryori (monks’ ascetic cuisine) — dainty bowls of mountain vegetables that are pickled, brined, fried or marinated. When on pilgrimage, the Yamabushi eat in silence and chew each mouthful 30 times as a form of meditation, so as I enter the dining room at 6pm that evening, I figure it makes sense that every mouthful has to count — and the tastier the food is, the better.

What I hadn’t bargained for was eating Saikan’s shojin ryori in the dark with my hands. My dining companion, Takeharo Kato — another Yamabushi priest who’s sharing my training with Hayasaka — believes that blackout sensory deprivation will heighten the meditative experience for me. “Every single plant and food is a gift from the deities,” he explains, employing the same sort of effective, calming tone I’ve heard yoga instructors use as he cuts the lights.

As my eyes adjust, I can make out the crescent lips of tiny bowls and plates scattered across the table. “Try to sense the texture of the water,” he says at the start of the meal, instructing me to sip from a palm-sized cup that I search for gingerly with outstretched fingers. “Imagine how it’s circulating around your body and how your body is absorbing it.”After dinner, Kato takes me on a walk across the mountain summit in the dark, our feet stumbling over steps, tree roots and potholes, a bear bell slapping against his thigh as we shuffle out into soupy moonlight in search of stars. By the time I retire to my room, my inner state of quiet feels intertwined with the cocooning silence of the lodge.

Sacred summit

The holy mountains of Dewa Sanzan were opened up for spiritual worship by a prince called Hachiko in 593 AD, and when I venture out into the cool mountain air the next morning I find there’s a surprising number of sacred sites at the summit. Hachiko’s shrine is here, as well as his overgrown grave. On the same summit plateau, where locals from nearby villages are pruning hedges and cutting the grass, there’s the gigantic rose-red Dewa Sanzan summit shrine, with a thatched roof two metres thick in places, fronted by a small fenced-in lake.

It might not look like much, but this lake is one of Dewa Sanzan’s most sacred sites. “It’s quite strange to have a lake on top of a mountain,” says Kato. “For centuries, there’s been a belief that this is a sign of the presence of the gods.” Archaeologists have dredged up bronze mirrors — sacred objects used in both Shintoism and Buddhism in Japan — thrown into the lake by pilgrims, dating to around the eighth century, and today it’s known locally as the mirror lake. We recite our prayers in the presence of a small scattering of tourists who have come for blessings at the shrine.

My final stop is the shrine itself, for a ceremony in the inner sanctum to mark the culmination of my training. As we kneel and then bow, preparing to chant, I’m desperate to look up at the gilt altar and the high priest’s robes as I sense I’m being wafted by talismans and showered in rice. But I know by now that I mustn’t raise my head, and I don’t.

“You should keep your head low when praying because the kamis (deities) won’t turn up if you’re looking at them,” Kato reminds me afterwards. “The invisible elements of the world are a key aspect of what we want to share with you. If we can sense invisible things, we can regain our sense of wonder.” Amen to that, I think to myself. It’s not quite a spiritual rebirth, but maybe I’m on the verge of an awakening.

Wondertrunk & Co creates custom itineraries and can organise a range of Yamabushi experiences, from one-day introductions to seven-day training programmes. A three-day experience costs from £1,500 per person, including meals and accommodation but not flights, and can be combined with other Yamagata tours or a broader Japan itinerary.

This story was created with the support of Wondertrunk & Co.

To subscribe to National Geographic Traveller (UK) magazine click here. (Available in select countries only).