Embracing the unknown in Big Bend National Park

National Geographic Photographer Filipe DeAndrade scouts for wildlife in Texas’ biggest national park.

Big Bend National Park sits in a spot of far West Texas where fields of cacti meet limestone canyons carved by rivers. This vast stretch of wilderness is often referred to as three parks in one thanks to its distinct ecosystems—river valleys, desert, and mountains—and is home to hundreds of species of wildlife, including 75 species of mammals and over 450 species of birds.

While the national park is a wildlife photographer’s paradise, it’s not always easy to find wildlife across the park’s more than 801,000 acres. This remote and rugged terrain requires determination and a willingness to embrace the unknown.

This is exactly why National Geographic Photographer and Explorer Filipe DeAndrade loves visiting Big Bend. For DeAndrade, who travels the world in search of wildlife encounters, the challenge and the reward of wildlife photography is getting to where the animals are.

"Being a photographer is all about putting yourself in position to capture the best images. It's all about getting out there," he says.

The sun has just risen in Santa Elena Canyon, one of the park’s most dramatically beautiful spots on the border of the US and Mexico. DeAndrade is on a mission to scout wildlife in some of Big Bend’s hard-to-reach places in the GMC Canyon AT4.

To begin his day, DeAndrade wades into the Rio Grande, the mighty river that runs for over 100 miles through the park, to take photos of the canyon’s 1500-foot limestone cliffs in the early morning light.

DeAndrade is particularly excited about the possibility of seeing migratory birds during his scout, since Big Bend is located along a major avian flyway. Eager to explore the park, he packs up his camping and camera gear and heads to the GMC Canyon AT4.

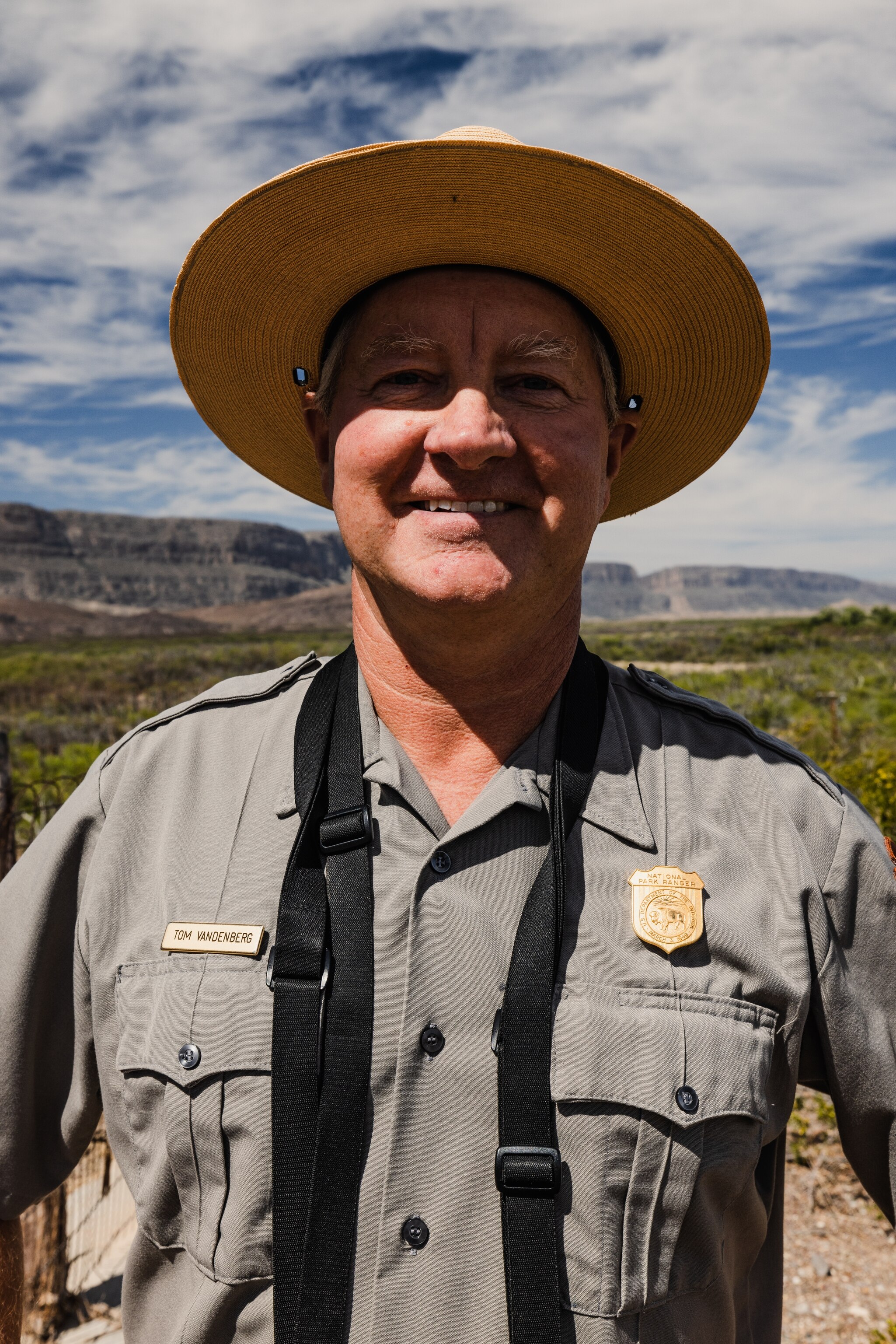

His first stop is the Castalon Ranger Station where he meets Big Bend park ranger Tom VandenBerg. Park rangers are an invaluable resource for wildlife photographers as they have all the details on road closures, weather conditions, and of course, wildlife sightings.

“Being able to anticipate where animals are going is a skillset that doesn't come easy. That's why you work with experts like Tom,” says DeAndrade.

For the best chance at spotting wildlife, VandenBerg suggests that DeAndrade head to the Rio Grande, then towards the Chisos Mountains and Mule Ears, a distinctive rock formation that resembles the ears of a mule. By visiting these locations, DeAndrade will have a chance to scout for wildlife in several of the park's ecosystems.

Having touched base with VandenBerg, DeAndrade prepares his route and charges his camera batteries using the GMC Canyon AT4’s 120V truckbed charger. He chooses his first destination—an area along the river—and selects off-road drive mode to navigate some of the park’s less-maintained dirt roads. Having a vehicle that can handle the backcountry saves him time that he would normally spend hiking to each point.

When photographing wildlife, it’s best to be prepared at all times of day. Many animals are elusive or nocturnal, so DeAndrade decides to set up trap cameras (hidden cameras that are triggered by movement) in spots known for wildlife activity.

“Animals are the worst actors. They never show up on time,” DeAndrade says. “I can use trap cameras to get images when I’m not there. They’re like a spy in the wild.”

In a sandy stretch along the Rio Grande, DeAndrade discovers coyote tracks and his face lights up with excitement.

Coyotes are among Big Bend’s apex predators and prey on rodents and other small mammals in the park. Their tracks have four toes and claws on each foot, with the front paws slightly larger than the back paws. DeAndrade can immediately identify these tracks as coyote tracks, since unlike the big cats that also roam Big Bend, coyotes walk with their claws extended.

DeAndrade explains why this location by the Rio Grande is an ideal place to set up a trap camera. “Animals will always take the path of least resistance," he says. "This is along a hiking trail. That means they’re going to come in here to snag some water.”

After checking on the position of his trap camera by the river, DeAndrade heads to Lost Mine Trail, a 2.4-mile path that rises 1,100 feet in elevation and winds through the Chisos Mountains past all manner of flora. He bounds through wooded grassland until he finds the perfect place to set up another camera.

DeAndrade finds a scenic overlook where he thinks a bobcat or mountain lion might pass through, and to determine the best positioning for the trap camera, he gets on all fours like a cat.

"It's all about getting in the mind of the animal," he says.

To DeAndrade's delight, as he sets up his final trap camera, he spots swifts — fast-flying birds often found near rocky cliffs and canyons — passing by overhead. He takes it as a sign of more wildlife sightings to come either in person or from his hidden cameras.

As the sun begins to set, DeAndrade drives confidently through the park on paved roads and backcountry roads, soaking up the beauty of the surrounding landscape and reflecting on how leaning into unknowns leads to the best adventures.

"Settling into a circumstance where all you do is have hope that it's going to turn out okay and rely on your skill set, your passion, and your motivation to get you through ... that is where the magic happens," he says.

Being a wildlife photographer certainly has its challenges — getting to where the animals are and waiting for them to show up requires immense patience — but DeAndrade can't imagine doing anything else.

"It's the easiest job in the world because my passion drives me to be out in nature chasing that next wildlife encounter," he says.