Messages on the mountains

For ancient peoples living in and around the AlUla Valley, the sandstone mountains rising from the desert were not just part of the landscape, they were surfaces on which words, names, prayers and images could be engraved. They remain to this day - legacies, carved in stone.

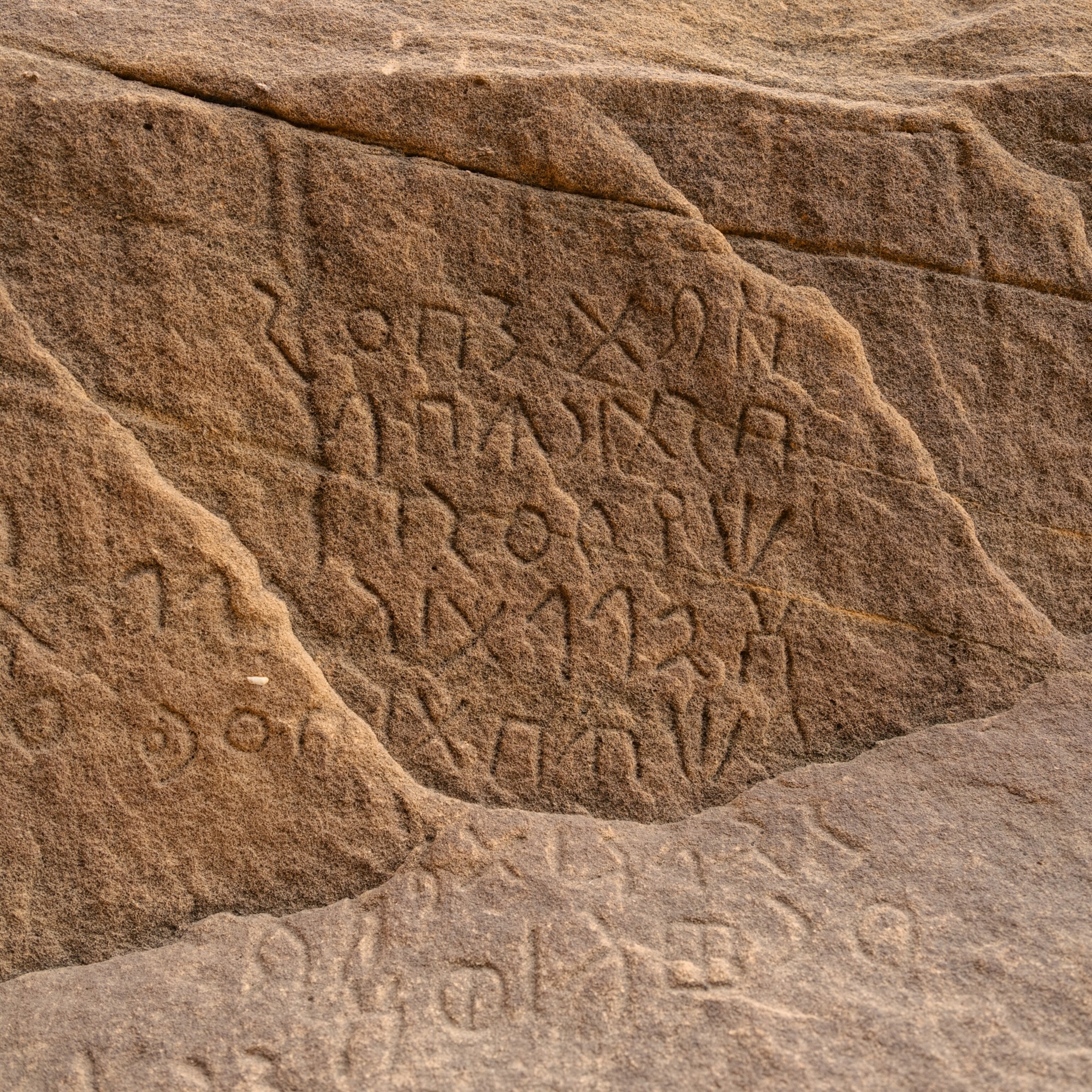

In and around the AlUla Valley loom vertical sandstone cliffs. Many of them now display depictions of human figures or animals known as petroglyphs, a term derived from the Greek words petra, meaning “rock”, and glypho, meaning “to carve”. Ancient artists would use stones or tools to scrape images onto the surface of cliffs and freestanding rocks—or, in some instances, they would carve figures or lines of text in relief, standing proud of the rock surface.

The AlUla region is home to thousands of these petroglyphs, taking different forms and spanning centuries of time. Ibexes, camels, horses, ostriches, and many other species cavort across the rock faces, some pursued by stylized human hunters holding spears and other weapons. Other images depict large urns and include complex decorative patterns. What were these petroglyphs for? We cannot be sure, but the human urge to represent the natural world in art, and to record the great events of life, has shown itself in every culture and every society.

In the north of the AlUla Valley rises the mountain known in Arabic as Jabal Ikmah. This is a particularly rich repository of images and texts that have managed to weather centuries of sun, wind, and rain with remarkably little deterioration—so rich that Ikmah has become known as an open-air library, even though its origin appears to have been as a place of worship rather than study. Some of its hundreds of inscriptions may be as much as 2,500 years old. Most offer tantalizing insights into life and culture during the period when the Lihyanite kingdom flourished in this region of northwest Arabia, roughly from the fifth to the first centuries B.C.E.

The Lihyanite capital, Dadan, close to Jabal Ikmah, was an important city and way station on the routes of the camel caravans that facilitated long-distance overland trade. Luxury goods such as frankincense sourced from south Arabia would arrive in Dadan for onward shipping to markets in Egypt, around the shores of the Mediterranean, and beyond. The inscriptions carry multiple complex meanings, but it is thought that some of the merchants and traders in Dadan who controlled these shipments may have recorded their offerings to the Lihyanite god Dhu Ghaybat—sometimes alongside prayers for reward and favor. Many of these lines of text, etched and carved into the mountain and on fallen boulders in a deep gorge, are still clear today, written in a local script called Dadanitic* that omits representation of vowels within words.

Using a simplified transcription system, one, for instance, reads: “Wshh son of Wdd of the lineage of Dmr performed the zll ceremony for Dhu Ghaybat and so may he favor him and may he help him and his descendants.” The zll—mentioned many times in these inscriptions—seems to have been a ritual of homage to the deity. We can only guess at who the named individuals might have been. Another inscription records: “Ssn priestess of Dhu Ghaybat organized the zll ceremony for the sake of her palm trees in Dmn.” And again: “Mhrh son of Gdn of the lineage of Wtmt performed the zll ceremony for Dhu Ghaybat.” And: “Thbb daughter of Abddktb performed the zll ceremony for Dhu Ghaybat for what she has in Bdr and so favor her.”

And so on. Name after name of perhaps earnest, nervous, or pompous worshippers and beseechers, offering us tiny glimpses of their lives as they seek good fortune for themselves, their crops, and properties.

Ikmah also hosts a few texts in other languages—Thamudic, Minaic, Nabataean, and even early Arabic—but the majority, carved in Dadanitic, come in different types. Some are dedications, while others are what we might recognize today as simple graffiti: “Blns the horseman,” or just a personal name scratched into a rock: “Nfn Nfn” “Whblh” “Sr daughter of Zd”.

Others are more formal, perhaps the work of professional scribes, and sometimes mentioning the names of kings or rulers: “Hny priest of Dhu Ghaybat performed the zll ceremony for Dhu Ghaybat in the year 20 of Tlmy.”

Who was King Tlmy? When did he rule, and over precisely what area? Scholars continue to investigate these and many other questions surrounding the lives and history of the people of Dadan.

One ongoing field of inquiry surrounds the place names mentioned in the stone-carved inscriptions. Some archaeologists have identified Bdr as lying to the south of modern-day AlUla, though others dispute that. Dmn may have been in the north, around what are now the borderlands between Saudi Arabia and Jordan. Since both places feature prominently in Ikmah’s open-air library, confirming their locations would mean the Lihyanite kingdom’s influence may have extended many hundreds of miles from Dadan itself.

The insights that the inscriptions of Jabal Ikmah offer into the history of this part of Arabia continue to enhance our understanding of the economic, political, social, and religious lives led by the people of the AlUla Valley more than two thousand years ago.

*Dadanitic—the script in which most of the inscriptions at Jabal Ikmah were written—omits representation of vowels within words. In addition, it includes many sounds for which English has no written equivalent. The transcription system we have used in this article has been simplified to facilitate understanding for non-specialist readers.

Journey through time to discover the rich history of AlUla here.