Standing Stone Circles: The most ancient builders of Northwest Arabia

Among AlUla’s thousands of archaeological sites, the excavations of five standing stone circles are rewriting long-held assumptions about early Arabia.

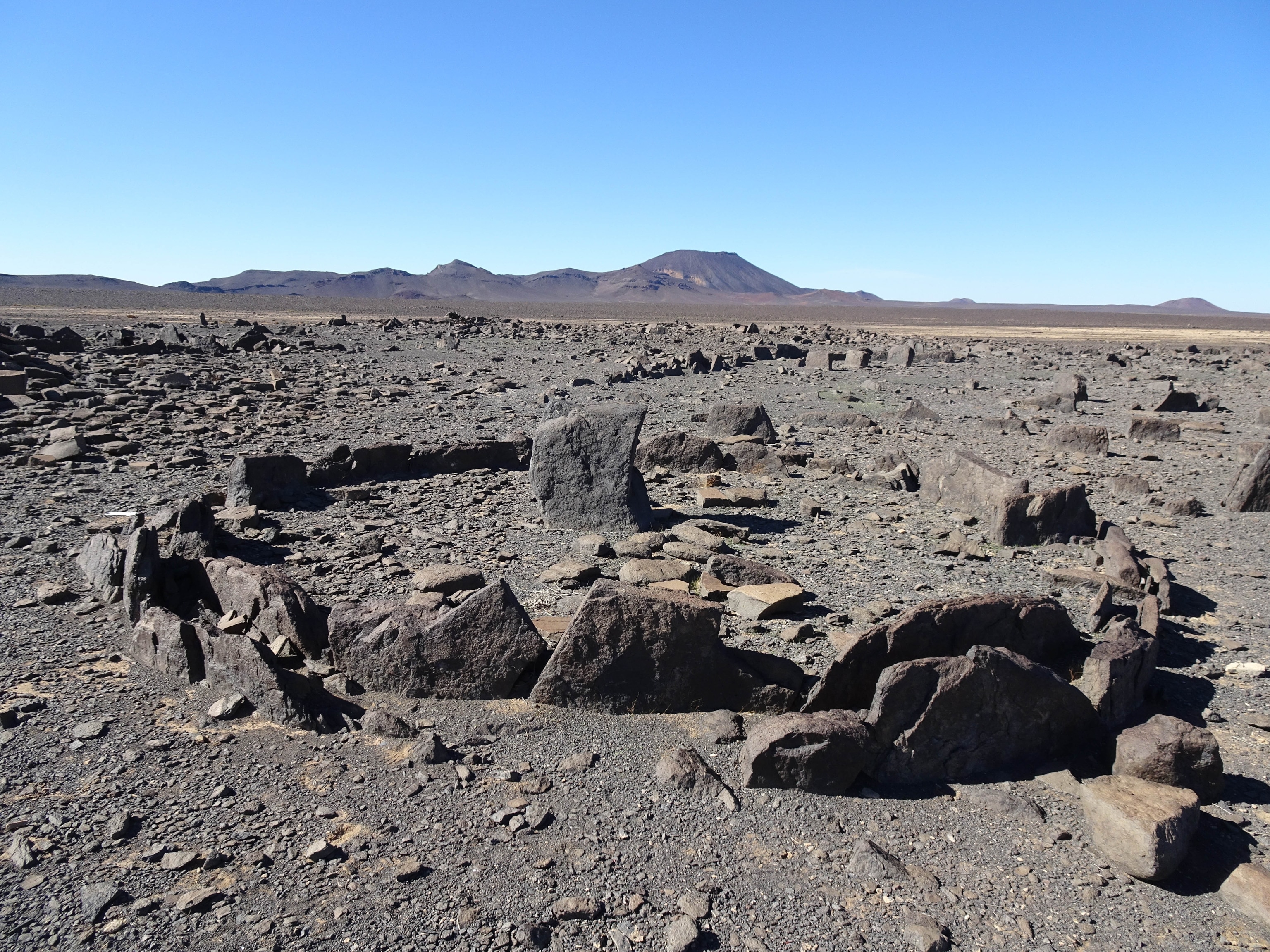

A wind whips up dust on the desolate landscape of Harrat Uwayrid, the volcanic plateau that rises above the sandstone valleys of AlUla in Saudi Arabia. Across the flat plain, shades of gray-brown soil are punctuated by scatterings of dark, basalt rock—and a clearly defined circle of stones. Unmistakably constructed by humans, its low outer wall is formed by two concentric rows of upright stones with a single standing stone in the center. This structure was built around 7,500 years ago by a people we barely know for a purpose we have long misunderstood. Archaeologists call them “standing stone circles”: To the Bedouin, they are among the works of “the old men.”

In 2019, archaeologists from the University of Western Australia, funded by the Royal Commission for AlUla, began excavating standing stone circles, dubbed SSCs by archaeologists. Their working hypothesis was that these were cultic structures built by Neolithic nomads for some long-forgotten ritual. Excavating at multiple sites, what they found was archaeological pay dirt—domestic rubbish. The remains of hearth fires, discarded animal bones, household tools, and even jewelry, have reclassified the standing stone circles as domestic dwellings—Neolithic homes. Because early AlUlans were always believed to be nomadic, building such large and permanent structures is puzzling. Spread in their hundreds across AlUla and some in neighboring Khaybar, these standing stone circles are rewriting the region’s history.

Standing stone circles seem to have sprung up quite suddenly, appearing from around 5,800 to 5,500 B.C. This coincides with a warmer climate in the region that brought more regular rainfall and a savanna-style landscape of grasses and acacia trees, good conditions for the domesticated cattle and goats we know these Neolithic people kept. But these were also good conditions for building permanent structures. More abundant vegetation meant less pressure to keep moving herds to fresh pastures, which made building homes more worthwhile. This, and the plateau’s abundance of handily sized flat basalt stones, may have encouraged the nomads to stay a while and build.

Almost all the standing stone circles follow one of two designs―designs that shows unusually little sign of evolution or development. It’s now believed that the concentric stone circular outer wall acted as a trench to support a timber frame covered by skins or vegetation. The enigmatic standing stone at the circle’s center was likely a brace for the roof support, with larger buildings having multiple internal stone supports. Each dwelling had a small doorway and an open hearth—either inside or out. Although there are some isolated standing stone circles, most are clustered together in groups with the largest sites comprising as many as 25 dwellings. Not only were these Neolithic people building homes for their families, but they also appeared to be coming together as communities.

Excavations of these settlements are revealing something of this people’s way of life. We know they kept domesticated cattle and goats to be butchered for meat, but they continued to hunt and gather, supplementing their diet with wild ibex, oryx, and hare, as well as foraged foods, likely including fruits, nuts, and grains. The large number of grinding stones found on the sites suggest inhabitants were regularly milling grains, but these were likely to be gathered rather than farmed. The plateau sites have also revealed tools made with materials from the sandstone valleys and jewelry shaped from shells from the Red Sea—these Neolithic people had a complex culture involving travel and probably exchange.

Indeed, despite building such permanent structures, Neolithic communities probably moved from place to place on a rotation, spending varying amounts of time at each location. Perhaps responding to fluctuations in the weather—a string of warm winters or an especially dry summer—they might stay at a site for a season or longer before moving to another site that better suited the latest weather. And when conditions were right, they seem to have moved their herds down from the plateau to the sandstone valleys, where the near absence of standing stone circles suggests they adopted a different way of living. These were a people adept at adapting to their environment and the resources it offered.

Around the same time, monumental Neolithic structures called mustatils begin to appear. These huge stone rectangles, some as long as 2,000 feet, were almost certainly built by the standing stone circle people and used for rituals. These seem to have centered on the placement of the upper cranial parts of horned animals, including domesticated cattle and goats, perhaps as offerings or as sacrifices. With around 1,600 mustatils across northwestern Saudi Arabia, their unprecedented distribution makes them one of the earliest known and most widespread homogenous sites for ritual practice in the world—pre-dating Stonehenge by around 2,000 years. Requiring a huge exertion of human labor, the mustatils may have also served as territorial markers, their size and permanence stamping the land around as belonging to a particular people—the standing stone circle communities. They are indicative of remarkable social cohesion—large groups of people with strong shared beliefs and an ability to work together for a common cause.

It’s believed that the region’s climate dried during the fifth millennium. As the grasslands shrank and water grew scarcer, Neolithic people needed to move their herds more regularly, and eventually they stopped keeping cattle—preferring hardier animals better suited to the drier conditions. By 4,500 B.C. the standing stone circles seem to have fallen out of use. Many doorways are sealed, probably to secure the dwelling while inhabitants were away. Their intention may have been to return again when conditions were suitable, but, instead, they kept moving. Their descendants did return, but rather than reoccupy the houses, they built tombs in which people were interred. For hundreds of years, these tombs were built within the settlements, on and adjacent to the standing stone circles. The new structures spread along well-trodden paths between these settlements to form what are now known as “funerary avenues.” That people kept returning to these sites is perhaps indicative of a collective memory—an innate appreciation that these places were important.

Only now are we beginning to understand how important these sites neglected for millennia really were―and are. The revelation that standing stone circles were domestic dwellings overturns many of our assumptions about Neolithic AlUla. Here were a people more settled, more sophisticated, and more socially cohesive than history has given them credit for. Their story is just beginning to be revealed, but already a very different picture of early AlUla is emerging.

A herder urges his flock of goats across the savanna. Their bleats carry over the landscape to a cluster of circular huts that the herder and his family call home. Outside a doorway, an open fire burns and the aroma of roasting meat lingers in the air. Children play while a woman grinds grain between millstones and a man shapes a piece of stone into an arrowhead. In the distance, smoke rises from the fires of other dwellings. The herder considers the warm breeze stirring the dry grass: Perhaps it is time for his people to move on.

Journey through time to discover the rich history of AlUla here.