Will the resumption of human spacecraft launches lead to a rebirth of Florida’s Space Coast? The anticipated blastoff of a SpaceX rocket carrying two NASA astronauts could herald the return of the boom years for this 72-mile stretch of shoreline east of Orlando.

On May 30, if everything unfolds according to plan, the reusable Falcon 9 rocket will launch its Crew Dragon capsule on a mission to the International Space Station. It will be the first U.S. launch of American astronauts since 2011. When it lifts off, all eyes will be on the skies.

But there’s also a world to discover underfoot. Alongside NASA’s Kennedy Space Center, migratory birds fly and West Indian manatees swim. Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge, the 140,000-acre marshy expanse surrounding the launch area, is a vital habitat for endangered and threatened species.

“You’ve got a center of next-wave technological advancement, and they’re doing it right here in a national wildlife refuge,” conservationist Duane DuFreese tells us.

Everyone wants to feel the heat on a launch. When I got here in ’59, I saw my first, and the amount of noise was intense.Walter Starkey, Docent, Kennedy Space Center

Although COVID-19 has recently stalled tourism here, many are hoping that an ongoing schedule of launches will be the engine to get it started again. When visitors return, they will be able to witness thunderous rockets and explore one of Florida’s most spectacular habitats.

Blasting off

If any place in Florida knows a thing or two about resilience, it’s the Space Coast. After the boom and bust years of the 1960s Apollo program, then the rise and fall of the Space Shuttle program (1981-2011), this area is finally buzzing again thanks to private spaceflight enterprises led by SpaceX, Blue Origin, and others.

Most people watching the blastoff will be doing so virtually, as NASA has urged spectators to do. Kennedy Space Center isn’t allowing guests onsite during the launch. Those who do decide to observe in person from afar should follow local county rules—including social distancing and keeping in groups no larger than 10 people.

At most points along the Space Coast and elsewhere in Florida, the beaches and parks are open. Come Saturday, surfers off Cocoa Beach will surely pause to peer up from their boards at the show in the sky. Long before the launch time, RVs likely will be angled in prime position along the Banana River, staking their spots.

And in Titusville, just across the river from Cape Canaveral, locations such as Space View Park frame views of the Vehicle Assembly Building. (The most beloved launch-viewing spot—on the beach at Playalinda, within Canaveral National Seashore—has been closed since March 19.)

One Titusville resident, Lisa DiMercurio, says she may head south to Satellite Beach to watch. “I always prefer to watch in Titusville, but a lot of people are stressing about how traffic will be,” she says. “This [launch] is a big one. Even people who’ve lived here a really long time get excited for these.”

Exploring Earth

Many will watch the launch on the beach, sand between their toes, looking for contrails corkscrewing in the air, listening for the sonic boom.

But what’s surprising about the Space Coast isn’t NASA but nature. The protected surrounds of the space facilities include not only the Merritt Island refuge, but also Canaveral National Seashore, the largest natural beach on Florida’s east coast, and the Indian River Lagoon, one of the most biologically diverse estuaries in North America. These native allures have mostly flown under the tourist radar.

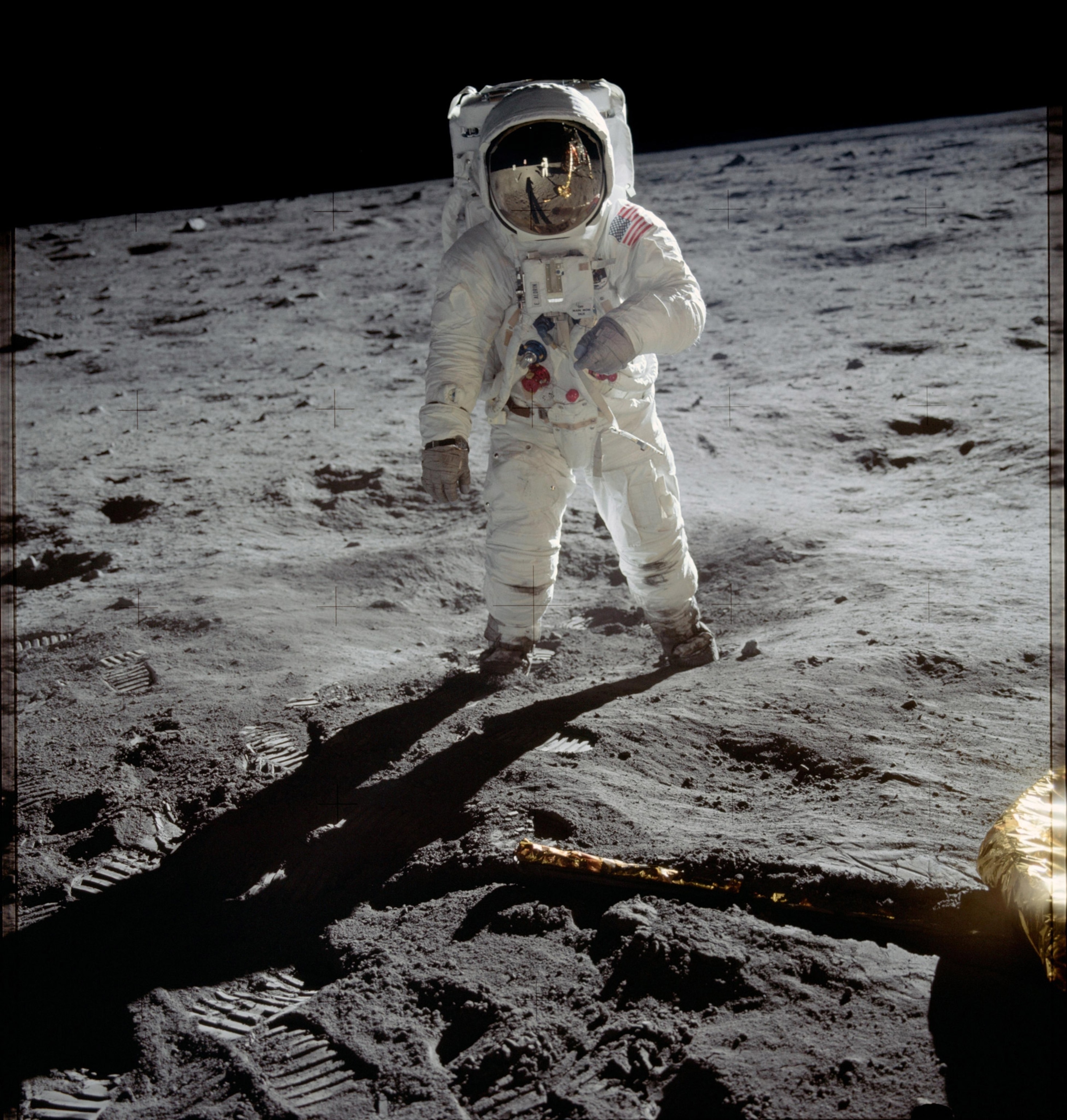

I heard about the moon landing for the first time in third grade. I was so shocked when I heard that a man had actually stepped on the moon.Alyssia Pickens, Titusville resident

“You have to be here a little while to see it all, it’s more of a subtle delivery,” says DuFreese, executive director of the Indian River Lagoon Council, a conservation group.

It’s a subtlety that you have to search for along Cocoa Beach’s commercialized oceanfront artery, A1A—lined with surf and souvenir shops, churches, and motels, pawn shops, and strip bars. Behind all the concrete, this part of Florida stays wild.

The beaches of Canaveral National Seashore see an average of 6,000 nests laid each year by four of the world’s seven sea turtle species. During the 2019 nesting season alone, 13,383 turtle nests were recorded along the park’s 24 miles of beaches. With nesting already underway since April this year and visitation still nonexistent, only the turtles can tell what 2020 will bring—but it’s sure to be bountiful.

To the north, the town of Titusville is lower-key, slightly scruffy, and less obviously chasing the tourist buck. This has long been where space workers and even the astronauts themselves had homes.

A last vestige of the Apollo era and named to honor its missions, the Moonlight Drive-In (open more or less only when it feels like it these days) is the place to have a hand-dipped milkshake and fried shrimp platter delivered to a tray hanging off your car window (socially distanced dining at its best).

From there, it’s a short drive across the A. Max Brewer Causeway and the Indian River to enter Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge, which was purchased by the federal government in 1963 during the development of the Kennedy Space Center and is operated by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Fifth-generation Floridian and Titusville resident Laurilee Thompson, a volunteer for a citizen scientist program with the Marine Resources Council and the owner of a popular Titusville restaurant serving rock shrimp, regularly ventures into the refuge to test the waters of the surrounding Indian River Lagoon.

We were here during the launch of Apollo 11. The windows shook so badly that we always thought they might break.Raymond Hamod, Owner, Moonlight Drive-In

“Titusville’s economy is boom or bust depending on what’s going on on the other side of the river at the space center,” she says. “After the Apollo program ended, this community was decimated, people were giving away houses,” says Thompson. “Then the shuttle program came along and boosted us back up into normality again—until that ended. Now that all this renewed business is taking place out at the space center, we’re booming again.”

(Related: Discover a constellation of cool sites along the Space Coast.)

But the many new housing developments going up in Titusville as a result (and the run-off from the fertilizer and landscaping most Floridians can’t resist, too) are among the many manmade factors taking a toll on the lagoon’s health.

Arriving at a boat ramp at Mosquito Lagoon—one of the three bodies of water that make up the Indian River Lagoon—Thompson pulls out buckets and vials of chemicals to monitor water clarity, pH levels, and dissolved oxygen. She gets down to work as the shallow water around her simmers like a cauldron on low boil, bubbling with insects, mullet, and something else, too. “That’s a manatee with a cold,” she nods toward a sound that falls somewhere between a crow’s caw and an elephant’s trumpet.

Thompson mixes and shakes, recording the day’s water readings. “We want development but we don’t want to ruin our quality of life we have up here,” she says. “And our quality of life is certainly linked to the health of the Indian River Lagoon.”

The final frontier

During the summer months, there’s a Milky Way of sorts in the warm waters of the Indian River Lagoon. The glow, known as bioluminescence, can be seen with regularity in a few Caribbean lagoons and other spots around the world—but hardly anybody knows that this vibrant version of it also occurs along the Space Coast.

Locals often gather here in boats to see a night rocket launch. “A night launch is like a sunrise. It’s astounding. You can read by the light it puts off,” says native Floridian guide Chad Baesman.

Paddlers leave spark-like contrails in the water, the effect of single-celled plankton called dinoflagellates being disturbed by the motion of their movements through the water.

Mullet streak through the inky depths, too, leaving arcs just like rockets in their wake. An Indian River Lagoon summer night is a liquid show of splashes and streaking light. You can dip your hand into the warm waters, pump your fist, and watch the dinoflagellates glow like an X-ray.

There’s a galaxy in your palm and overhead. You don’t have to travel far to experience the wonder of the stars. Extraordinary things have always happened right here.