This small London museum contains a heartbreaking collection

For more than 200 years, children were left behind, often with these tokens as their only form of identification.

The Foundling Museum, in London’s Bloomsbury neighborhood, preserves a seemingly disparate collection of items. A small metal charm engraved with the name “Meriah Duchesne,” her date of birth noted as August 8, 1759. Coins from the same era, often altered with holes or notches to make them more distinguishable. A hairpin. Small padlocks. A liquor decanter label marked “ALE,” its chain long gone. A simple hazelnut, and an unexpectedly moving heart-shaped piece of red cloth, strangely anthropomorphized by what appear to be two outstretched paper arms. Hearts, in general, are a recurring motif among these pieces.

The objects are known collectively by the museum as “The Tokens.” Trifles, mostly, these small random pieces were left by parents, usually mothers, forced by poverty or the social stigma of their child’s illegitimacy, to relinquish their children to what was then called the Hospital for the Education and Maintenance of Exposed and Deserted Young Children. Used as identifiers in the case of the parents’ return, they now form a heartbreaking collection often overlooked by visitors to the U.K. capital.

Like Little Orphan Annie’s half of a silver locket, these trinkets are signifiers of hope, heritage, and remembrance that speak to us hundreds of years later as we still grapple with the legacy of children separated from family as a result of conflict, poverty, immigration policies, or other factors.

From lotteries to “General Reception”

Founded in 1739 by philanthropist Thomas Coram, the hospital began accepting infants under a “first come, first served” basis in 1741. Already overwhelmed with children by the end of its first year, it then switched to a lottery system in which parents were required to choose a ball from a bag. A white ball meant the child could be admitted pending a successful medical exam, black meant he or she would be refused a space, and red meant admission only if another child failed the medical assessment.

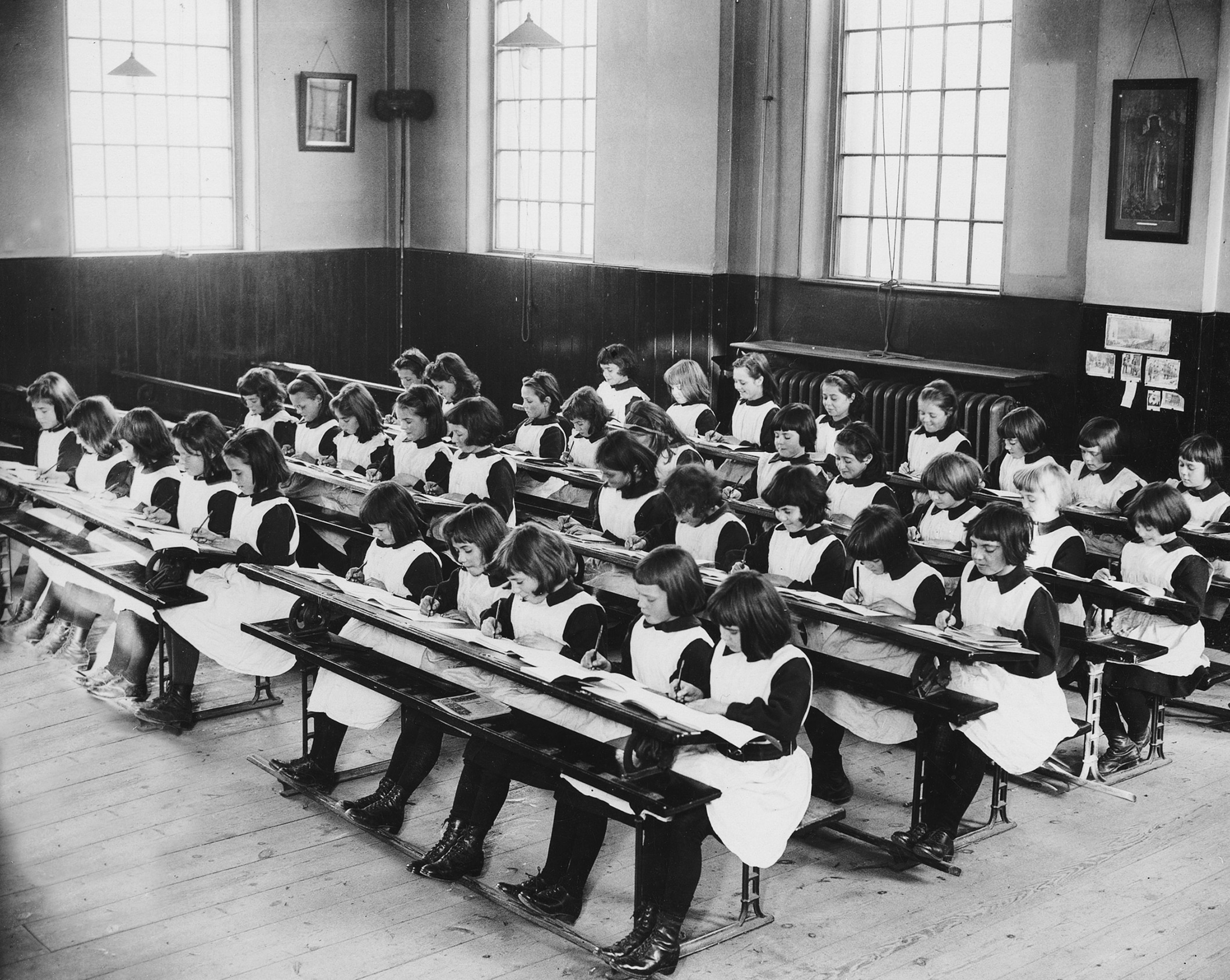

Carol Harris, the social historian of Coram, the children’s charity that began as the Foundling Hospital, notes that it was common for Londoners to show up at these lotteries. “It was seen as a form of entertainment in Georgian times,” she says. “The governors also fundraised from another public event, the ‘ladies’ breakfasts,’ when you could go and view the children eating.”

The lottery policy would continue until 1756 when the British government offered the hospital financial support with the caveat that the facility agree to take in every child under a certain age. The new scheme, known as “General Reception,” resulted in an enormous increase of admissions and continued until 1760 when the government rescinded its backing and the hospital switched to a petition/lottery system.

Until 1760, when the hospital started issuing receipts for children left in its care, no written records of any sort were kept regarding the mothers and fathers who entrusted their children to the hospital. As so many of the parents were illiterate, they would have been unable to leave a note or written statement as an identifier. Babies were identified only by a number recorded on a “billet,” a written form on which was also noted the child’s age, sex, clothing, and identifying marks.

The billet, along with whatever tokens were left, was then put in a packet, sealed with wax, and stored until a parent returned to make a claim. With no other method by which to identify and match families, the tokens became, for all intents and purposes, the only tether between parent and child.

Because the admissions process essentially wiped the child’s identity clean, the hospital engaged a practice of giving the children new names, many of which were either strikingly familiar or sounded as if they might have been lifted straight from a Beatrix Potter story. Isaac Newton, William Shakespeare, Biddy Tomkins, and Hopegood Helpless were just a few of the names given to foundlings.

Along with the three-dimensional objects, the collection includes a large number of fabric swatches, often sleeves or ribbons cut directly from the baby’s clothing by a hospital nurse. The fabric pieces, kept at a separate facility for conservation reasons and shown at the museum on computer screens, are said to be Britain’s largest collection of 18th-century everyday textiles.

A recent grant to Coram from the U.K.’s National Lottery Heritage Fund will allow the institution to digitize the textiles and other related ephemera, exposing them to a much wider audience.

Although its schedule is currently undecided due to the coronavirus pandemic, the museum usually presents a full roster of concerts, talks, and workshops. It is currently holding an online contest through June that challenges kids between the ages of six and 16 to write a chapter in the story of Hetty Feather, a fictional foundling created by children’s author Jacqueline Wilson, who has written a series of books about the character. (A British television adaptation is wrapping its final season this spring.)

(Related: Looking for more intriguing museums? Here are 15 of the world’s best.)

London stories

The Tokens also tell the complicated story of 18th-century London itself: an often dangerous, merciless city with rigid social mores and severe consequences for those whose lives dipped outside its conventions. It was a city whose resources were buckling under the weight of an increased population as more people migrated to the city in search of work. For children, death could be more of a certainty than life. According to the museum, London’s infant mortality rate in the early 1700s was 75 percent.

And yet, the British capital was on the verge of change, with institutions like the hospital beginning to exhibit some level of compassion toward poor and unmarried parents and their children.

Though the practice of leaving tokens became unnecessary after the introduction of the receipt system in 1760, Harris says, “the system was so established that babies continued to be left with tokens until the 1790s.” These objects comprise a collection, but each one carries its own poignant story of loss, desperation, and resilience.

Of the more than 16,000 foundlings admitted to the hospital between 1741 and 1760, only 152 were ever reunited with their families. The hospital closed in 1954 and is now called Coram. A main function of the organization is the creation of families as one of the U.K.’s largest adoption agencies.