This is America's Most Underrated Music Destination

With a camera in hand and a tune in head, photographer William Widmer chases a legacy through the isolated hills of the Ozarks in search of Arkansas’ storied musical past.

Some 90 miles northeast of Memphis, Tennessee, an unsung musical region touched by some of rock & roll’s most influential giants sits both quiet and proud in near isolation among the Ozarks. Here, in northeastern Arkansas, the dusty flatlands of the South give way to ominous, winding climbs that disappear along the thick, wooded mountain range before spitting out into open valleys. Carried up from Jackson County, a low whisper hitchhikes on the wind: the pluck of a banjo, the strum of an acoustic guitar, the purr of snare, and bellow of bass. These are the phantom sounds of a mid-century boom that swept the region in a haze of honky-tonk rowdiness and rockabilly riffs, where the likes of Johnny Cash, Elvis Presley, and Buddy Holly not only road-tested their sounds, but also fine-tuned the devil-may-care attitude that became the rock & roll we know today.

“You get your fill of establishment Elvis, after he’d made it, after he had beaucoup money and could do whatever he wanted,” says William Widmer, a photographer who set out on a four-day road trip throughout rural Arkansas to rediscover the region’s musical veins. “But these are the roots. This is where these people started out, and it’s humble beginnings.”

Though Widmer’s experience with the state is new, the Chicago-raised photographer is no stranger to the south. He’s lived in New Orleans since 2010, having moved there shortly after the Deepwater Horizon oil spill with loose ideas for work in mind, all based in temporality—he figured he’d stay six months, maybe. But the region captivated him, informing the human ecology arc his work has taken in the last decade, and it wasn’t long before the south turned from his geographic beat into his home.

Now, as he drives north, the first indication he gets that he’s crossed state lines from Mississippi into Arkansas is the earth itself. The soil turns from a deep black to a red, clay-like dirt. The roads start winding, hugging the varied topography that rests on the horizon. “There's a really unique beauty to the Ozark range,” says Widmer. “There’s a sort of nostalgia to a lot of these places, too. Arkansas [is] somewhat culturally isolated from the rest of the South. You don't need to drive too far to feel like you're off the beaten path, and then you drive into these tiny little towns that look like they haven't changed in 60 years—and that to me is kind of special as a photographer.”

What he’s looking for are remnants of a musical tidal wave that hit northeastern Arkansas in the mid-1900s, leaving evidence of its impact scattered across the land like seashells found curiously far from the sea. “If you want to vibe on the barebones, scrappy roots that gave way to a lot of the music that we can trace directly to what we all listen to now—Arkansas is a great place to start,” says Widmer.

The boyhood home of Johnny Cash; the honky tonk bars in the region’s one wet county where Elvis, Buddy Holly, Jerry Lee Lewis, Carl Perkins, Louis Armstrong, and others honed their practice; the oral history that lives on in its sole keeper, Sonny Burgess, a locally revered contemporary of the Sun Records crew who just couldn’t catch a commercial break—it’s all there.

"There’s an arc to the musical history of Arkansas,” he adds. “It started out in the hills and kind of trickled on down, or came over from Memphis, and built into a frenzy—this kind of frenetic rockabilly rock & roll—and that wave passed through. The musical tide. It was kind of unpredictable and wild. But it’s gone now. You’re left with these little pockets of the memories, all these shells scattered across the sand, a few creatures that are still kicking around on the shore. But nowadays, the music that they're playing is a little quieter, a little slower, a little more relaxed. But the evidence of that big wave is always there.”

Widmer’s pursuit takes him one hundred miles north of the state’s capital at Little Rock to the annual Arkansas Folk Festival in Mountain View. Under a flowery canopy of blooming dogwood trees, cultural demonstrations of frontier life unfold to the soundtrack of live folk, mountain, and bluegrass serenades that celebrate the area’s musical heritage. When the festival was founded nearly half a century ago to stimulate Mountain View’s depressed economy, the musical director—Jimmy Driftwood, a Grammy award–winning recording artist who frequented the Grand Ole Opry stage—made a deliberate choice to forego top-billing artists in favor of local acts playing regionally significant music.

It’s a choice that lives on today, not only at the festival but also just a few miles north at the Jimmy Driftwood Music Barn and Folk Hall of Fame, built by Driftwood and his friends in 1982, and where, by some accounts, he could still be heard playing tunes into his 90s.

“The show that I saw there could have been picked right up out of the 1930s or 1940s and plopped right down in 2017,” says Widmer of the modestly constructed barn that sits up against a gravel lot on the edge of town. The songs were upbeat and lighthearted, almost campy. “I met one younger girl there who I think was like 12,” Widmer continues. “And she's playing the fiddle with these old timers. The torch was being passed right in front of my eyes. She was the next generation tasked with keeping this musical heritage alive.”

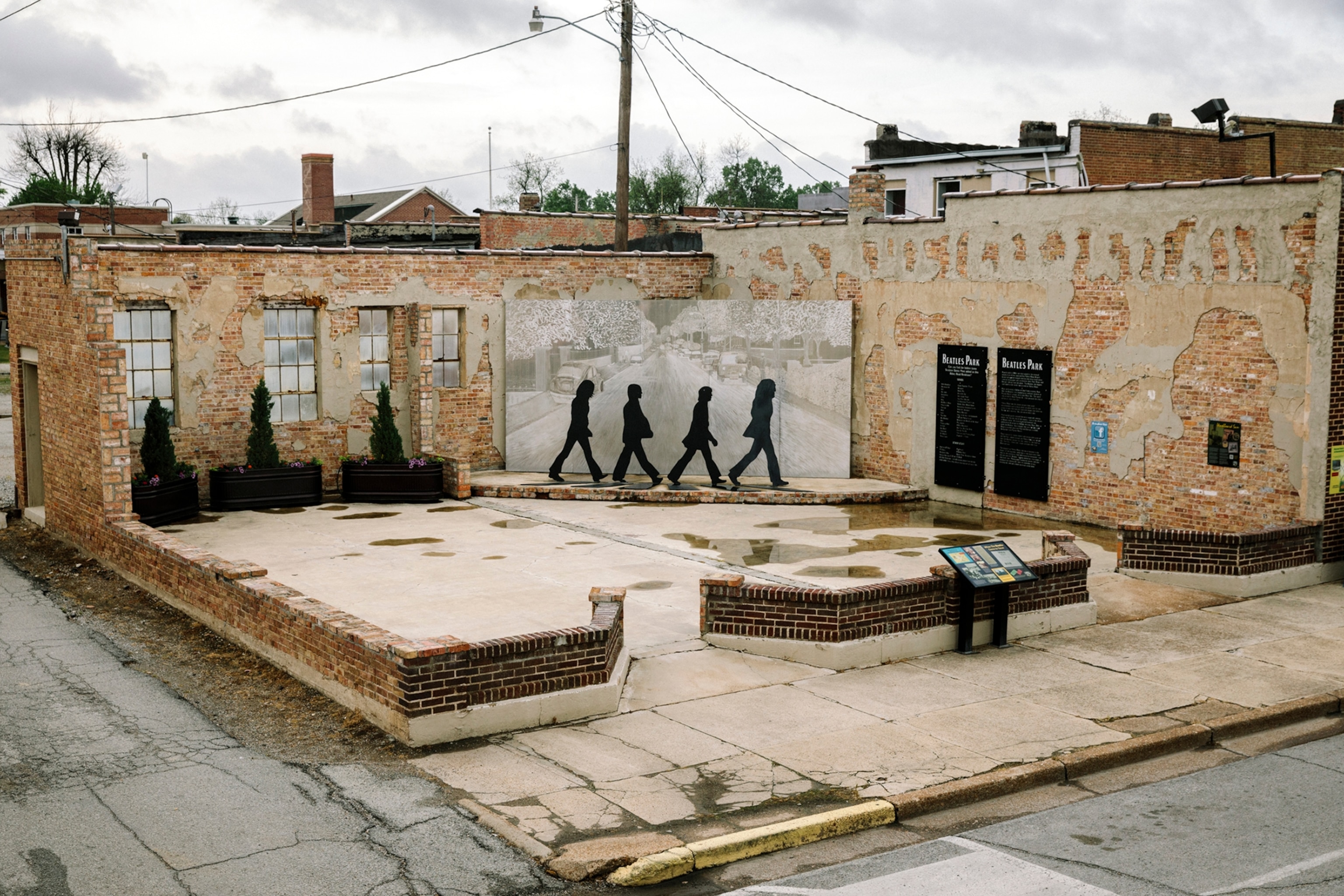

It’s a heritage that runs deep into that red earth, with a long history whose peak in the mid-twentieth century gave birth to rock & roll. A lot of it happened just 75 miles west of Mountain View in Jackson County, along what’s now called Rock & Roll Highway 67. But the stationary artifacts that played a role in that history—the clubs, the honky tonks—most of them burned long ago, leaving little more than a foundation here, some tile there, fragments of where raucous crowds once gathered.

All it takes is a slow, deep breath, feet rooted to the very spot where Elvis stood a half-century ago, lock-kneed in front of the mic at Charlie’s Place in Swifton, to be taken back to the 1950s, when honky tonks were booming, and big, chromed-out cars raced down the highway in the middle of nowhere. “That sort of DIY attitude that was surely required to pull off these nightclubs and these concerts, it comes to define rock & roll as we know it still to this day,” says Widmer. “The best way to experience Route 67 is to let your mind wander decades back as your odometer increases,” says Widmer. “For every mile you drive away from the city, you drive back in time.”

Back to when the Rock & Roll Highway was alive, passing fresh talent from Little Rock to the Missouri border. But it truly moved in Jackson. The sole wet county surrounded by dry ones, Jackson and its loosened alcohol laws drew crowds to the nightclubs, juke joints, and roadhouses that dotted the highway, bringing in enough cash to pay struggling musicians like Elvis, who toured the county four times in 1955. The mix of booze and music made the strip of Route 67 through Jackson County a destination.

Sonny Burgess is living proof. “I’ve been playing music ever since 1951,” the hall of famer tells Widmer as they sit among the photographs and memorabilia at the Rock & Roll Highway 67 Museum in Newport, Arkansas, Burgess’s hometown. “I started playing music here in Jackson County. Went over and got on Sam Phillips's record label, Sun. He released our first release in 1956, the last one in 19 and 60.”

A local legend who helped guide the rock & roll revolution along with his Sun Records peers, Burgess, now 88, still plays all across the county with his band, the Legendary Pacers. “He’s equally talented, equally respected by people who ultimately matter, like other musicians and music historians,” says Widmer, who had the chance to interview and photograph Burgess. “But he just never really had the commercial, mainstream success to the degree that people like Elvis and Buddy Holly enjoyed. So he’s been steadily playing his style of early rock & roll rockabilly for decades. He is living history.”

What Burgess represents is a testament to the entire region. “Topography, or the natural environment, informs the feeling of living history as much as the attractions you're going to go see,” Widmer says, “because people live in tiny little isolated mountain towns, much like their fathers and their grandfathers did before them. Life has changed everywhere, but maybe less so in rural Arkansas—and that's part of the beauty and part of the charm.”

The isolation that became so important to the area’s preservation—and, ultimately, to its musical incubation—really comes into focus as Widmer drives farther west still to Dyess, where a sweet, country home with deep cyan shutters, and a simple porch stands in protest against the otherwise uniformly flat Delta horizon. The boyhood home of Johnny Cash, both a museum and an altar to the legendary musician, sits as humbly as it did the day it was built in 1935. But it’s in that simplicity, that suggested loneliness, where Widmer inevitably finds what he’s been looking for—not so much an artifact as a feeling.

“You have to drive down this rough gravel road to get there, and before you get to the rough gravel road, you have to drive dozens of miles into the middle of nowhere. You can’t just get off the train and walk to his house,” he says. “For me, the coolest part about it was the house just pops up in the middle of nowhere. That’s the way it was. That’s where this stuff took place.”

The Cash family home opened to the public in 2014 as a museum in its entirety, furnished with custom-built pieces based on the memories of Johnny’s siblings. Occupied by the Cash family from 1935 to 1954, the home is part of the historic Dyess Colony, developed as an agricultural resettlement community during the FDR administration, wherein nearly 500 Arkansas families were provided a house, barn, smokehouse, and chicken coop under federal contract to supply goods in exchange for the property title. Now under the charge of Arkansas State University, the entire community is undergoing extensive renovations to transform the Dyess Colony into a heritage tourism site, with Johnny Cash’s childhood home at its center.

It’s that legacy—the one that people like Johnny Cash helped build, the one that Sonny Burgess still proudly sings today—Widmer’s been looking for proof of. But what he discovers is that Arkansas’s musical heritage is a lot like music itself: Sure, you can see it being made if you’re lucky enough to be there as it happens, but its heart doesn’t live in whatever artifacts or instruments may be leftover when the song winds down. Music, it’s about the way it makes you feel.

As Widmer leaves Arkansas, he does so with a tune in his head—the very rhythm of the state itself. “It starts out with just an acoustic guitar or banjo picking, maybe one solo voice,” Widmer says, his own cadence quickening. “It slowly builds as you come down out of the mountains, down into the flatlands in Jackson County, and the tempo would increase, and the volume might increase—and then the band would kick in. It would start to rock & roll; it might get rowdy. As the song keeps going, it plays out. It winds back down. And you’ve kind of—you’ve finished what you started.”

The photographer pauses.

“It’s just a guy on the porch with his guitar.”