One imagines Eleanor and Harris Phelps must have traveled with a great deal of luggage. Things tend to pile up during half a decade of world travel: clothes, toiletries, visas, curios … and, in their case, more than a thousand souvenir photographs.

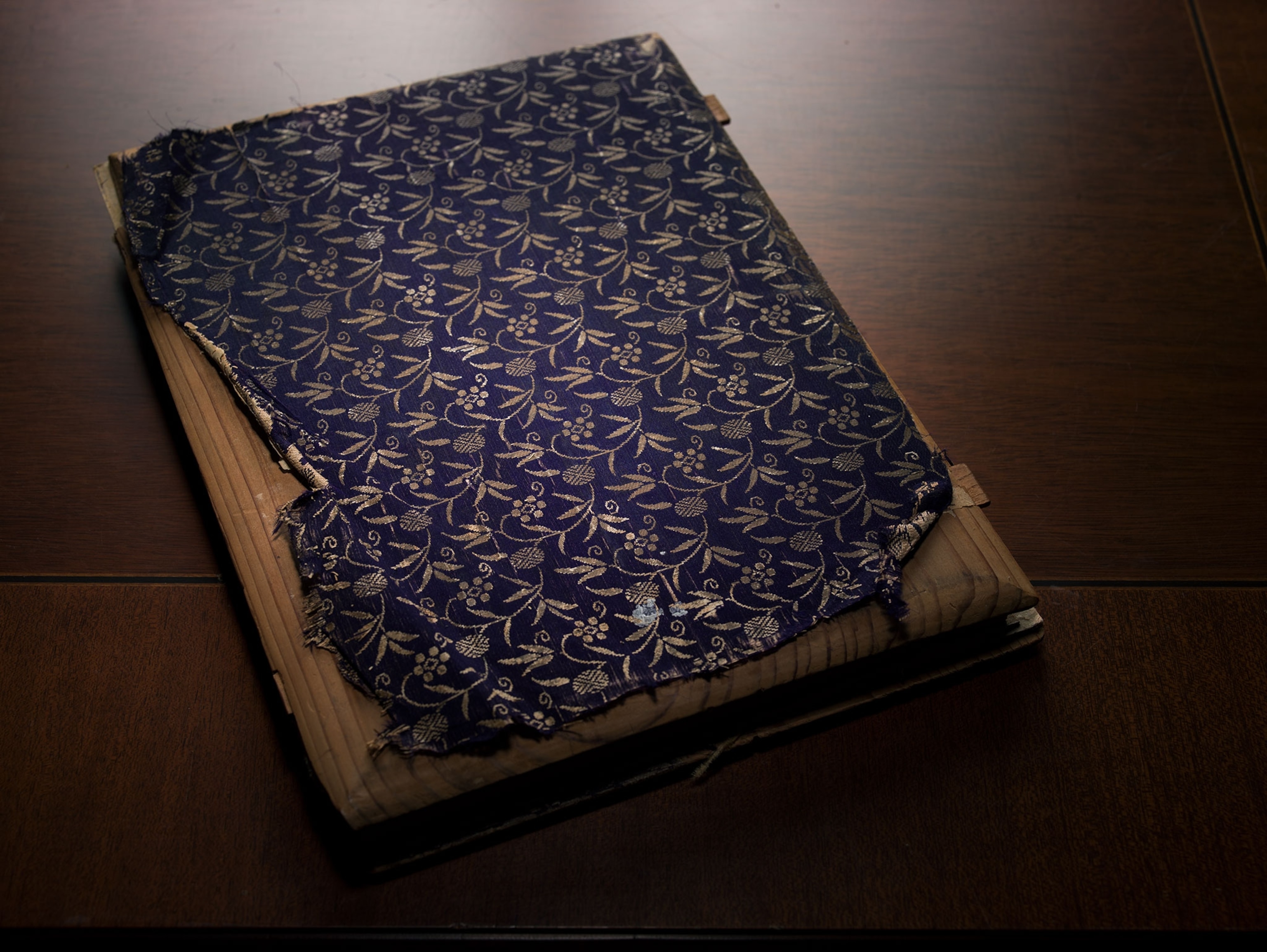

Handsomely bound in silk or red leather, the 27 albums of the Phelps Collection have been part of the National Geographic Society’s archives for over sixty years. But the pictures themselves are older still: Made in the last decades of the 19th century, in most cases they predate the Society’s 1888 formation. For all the care and expense that went into their binding, they’re aged and fragile, and senior photo archivist Sara Manco handles them with white cotton gloves.

“I love the size of the prints, the details that are captured,” she says. “I can look through a magnifying glass and see things I wouldn’t have noticed in a smaller print.”

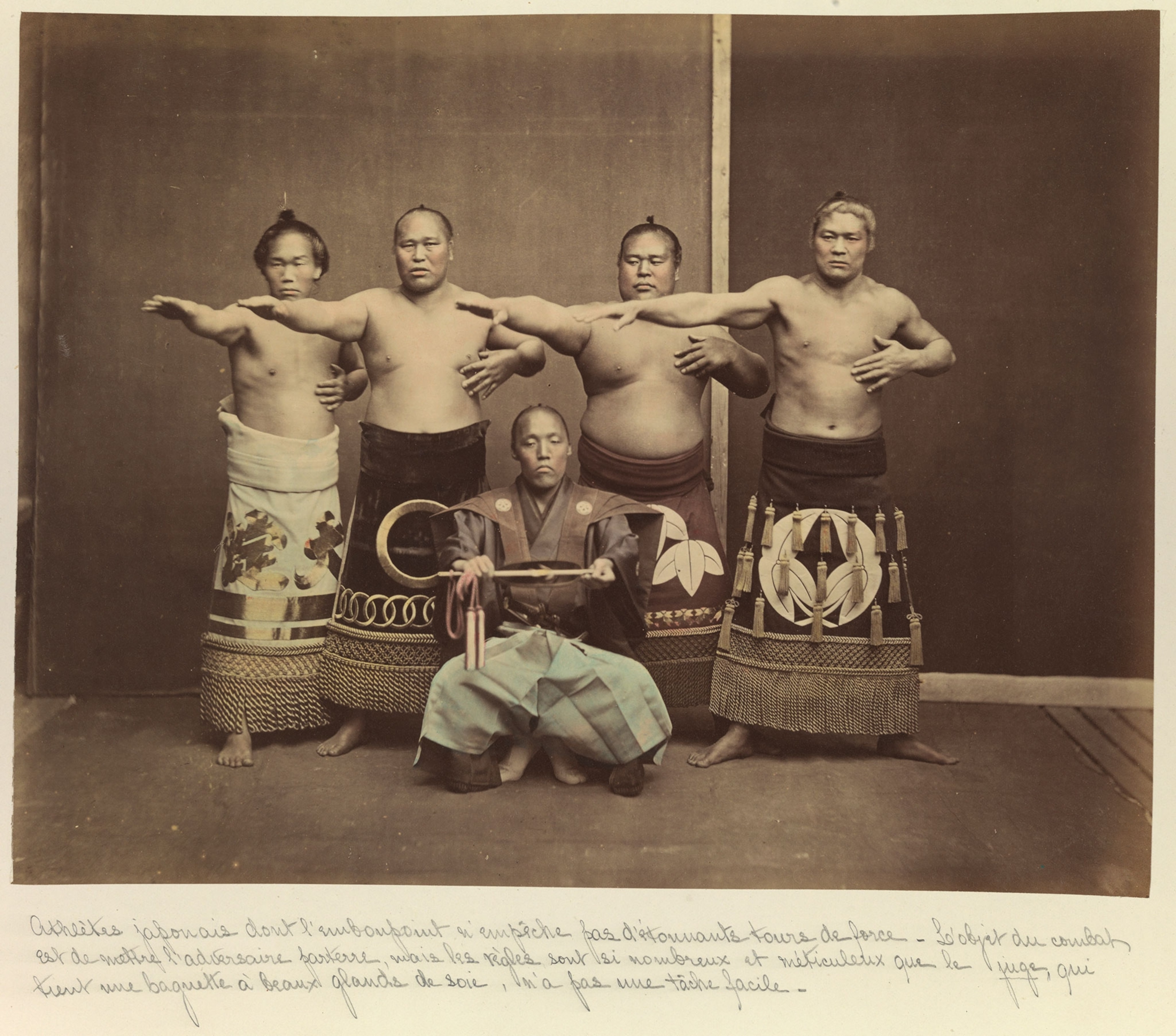

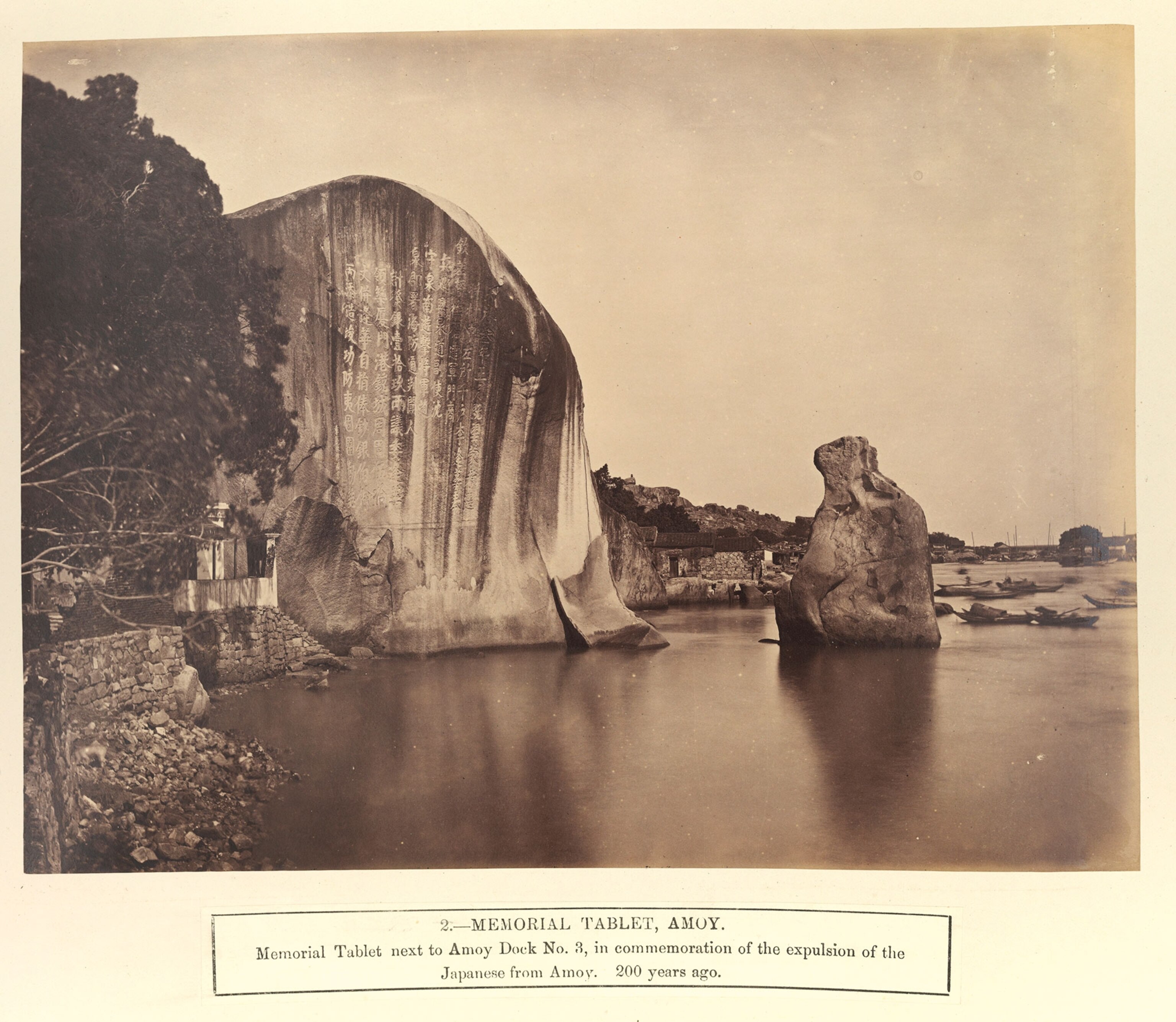

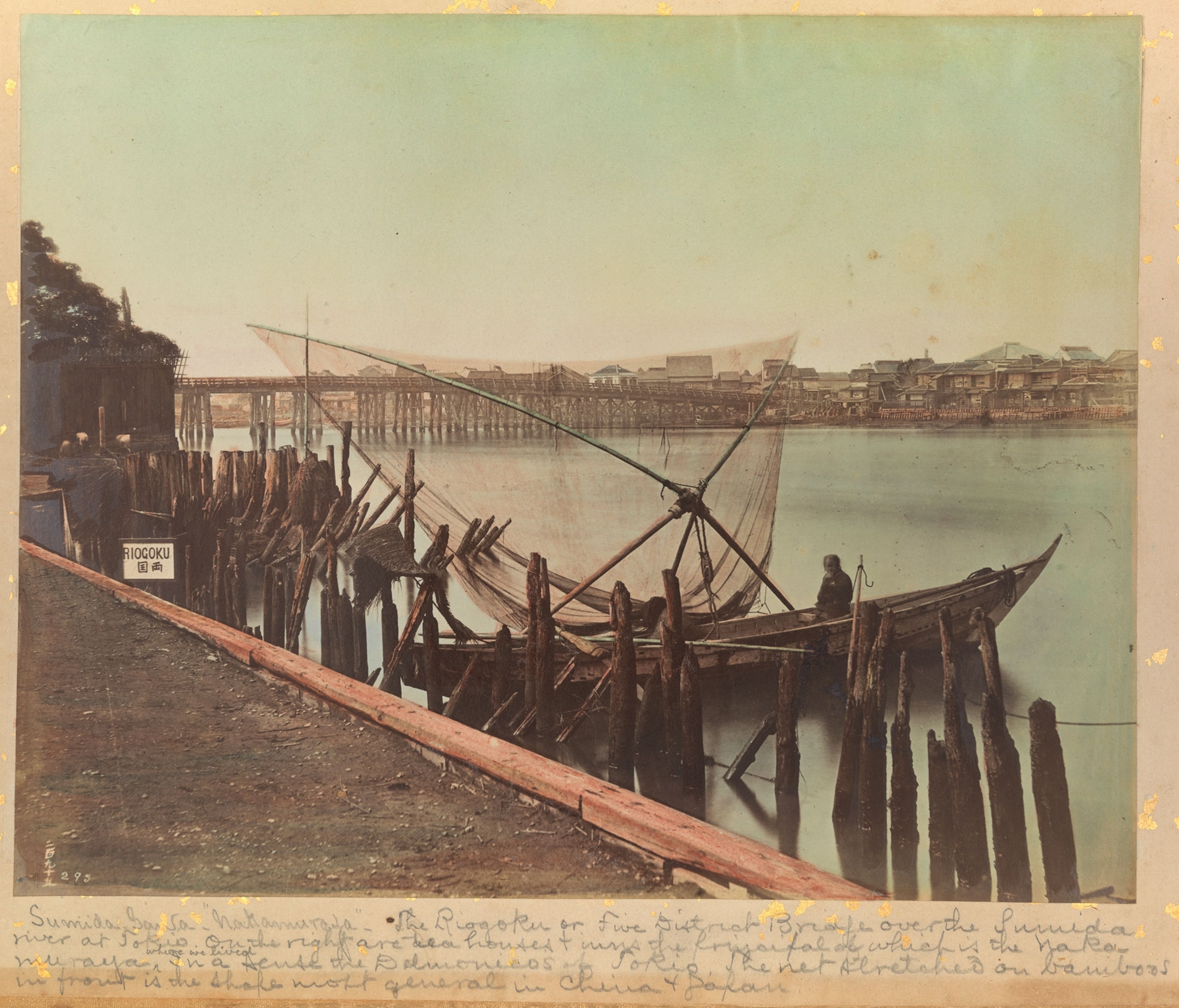

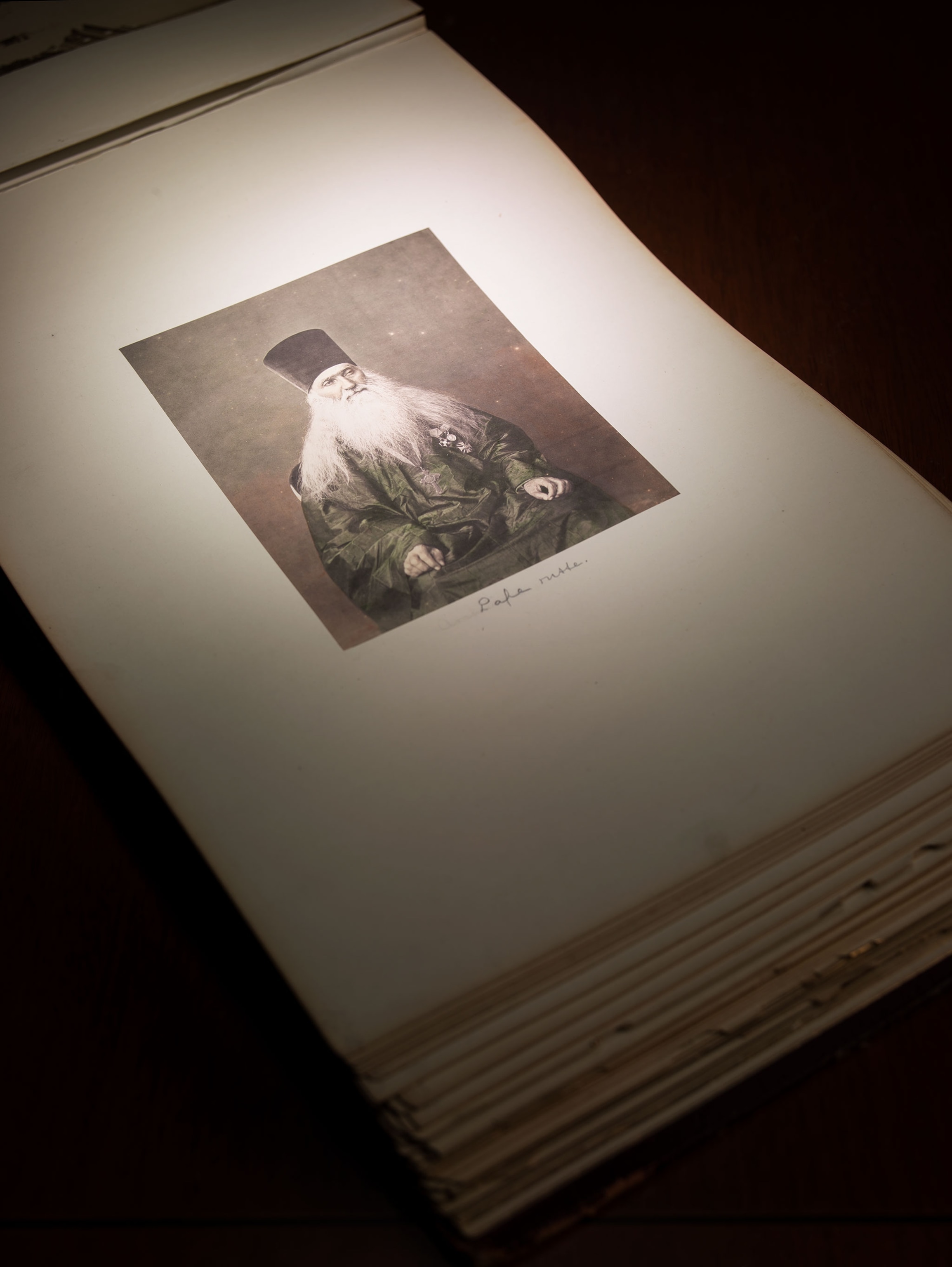

We lean over the images, engrossed: The edges blur, but some parts are sharp and fine as needles. In a German square, a boy shades his face and frowns directly at the camera; 7,000 miles away, a group of Javanese musicians does the same, arrayed in front of an ornate pavilion. Indigenous Siberians herd caribou. Armenian families, clad in traditional costume, pose for studio portraits.

“Having such a large group of images from so many different parts of the world before World War I is something very special,” Manco says. “But I also love the story behind them, that this crazy couple decided to travel the world. They covered a lot of ground without cars, airplanes, or any of the modern comforts.”

The Phelpses weren’t photographers. Instead, they collected souvenir prints from the 18 countries they visited from 1878 to 1883, meaning the images themselves could have been made anywhere from weeks to decades before the couple arrived. Yet the couple’s presence lingers in handwritten captions—Harris’s extravagant p’s, Eleanor’s elegant slant—and in the long, twisting story that delivered their keepsakes to National Geographic decades after their deaths.

For better or worse

Eleanor Livingston Pell was a New York high society beauty, scion of a wealthy, old family. Charles Harris Phelps was a Boston lawyer whose Puritan lineage was well-respected but not well-moneyed. In 1869, he came to New York City to make his fortune, “boasting he would marry money or not at all,” wrote the Times-Picayune. Nine years later, he met Eleanor.

The couple was fond of taking long horseback rides together; one day in the first wintry weeks of 1878, they eloped on horseback to Westchester. He was 32, she 20.

Eleanor’s parents, John and Susan Pell, were less than thrilled. John threatened to disinherit her. Initially appeased by the young couple’s agreement to formally, publicly remarry, the Pells were angered again when Harris whisked Eleanor away for a world tour.

In one way, these years are the most documented, thanks to the hundreds of photos they collected. They’re also the most private: Unreported by newspapers, related (if at all) in correspondence long since lost, the daily texture of Harris and Eleanor’s sojourn is now mostly left to the imagination.

It’s likely they first cruised to France, where the Pells had lived for decades. But from there? Maybe they went east and worked their way back home, sailing to Indonesia, Japan, and China before traveling overland through India to Western Asia and Eastern Europe. From Turkey, through the region then known as Persia, they crossed the Caucasus Mountains up into Russia, then to Western Europe. At some point, they toured the Mediterranean, because why not?

Today, an itinerary like that would make experienced travelers weep with both envy and anticipated exhaustion. In the late 1800s—without cars, rolling luggage, GPS—it would have been a feat of remarkable endurance, made possible only by considerable wealth. Eleanor, naturally, footed the bills.

The first hint of discord reared its head in Tehran, in early 1883, where a few army officers paid Eleanor undue attention and sent Harris into a jealous rage. The two separated for some time. Friends eventually convinced them to reconcile, and by that November, they were back on the road—at which point brigands pursued them as they rode overnight on horseback through a snowstorm on their way from Tabriz (in modern-day Iran) to Russia.

One wonders why they did it. It’s unlikely they were traveling for Eleanor’s ill health, as Harris later claimed: Such a marathon journey was more likely to harm than heal. Was it simply a shared love of travel? Entirely possible: Both had traveled and lived in Europe before marrying. As the years passed, though, it’s not hard to imagine the shine wearing off.

By 1884, they had settled in France. Upon hearing of the Tehran incident, Eleanor’s father demanded they divorce, but Harris persuaded Eleanor to stay with him. Their unity was short-lived: In September, a pregnant Eleanor left Harris to join her parents at their chateau in Pau, a town in southern France. But by midwinter the couple was traveling together again.

Charles Harris Livingston Phelps was born in Pau on May 15, 1885. His parents’ only child, he spent most of thirty years caught between them in a series of ugly, public disputes.

Love in the time of lawsuits

Over the next forty years, the Phelps family took legal action against each other no fewer than four times.

In 1887, Harris kidnapped their then-two-year-old son to coerce Eleanor to sign over half her income. Though both Harris and Eleanor attempted to keep the matter private, American newspapers latched on to the case. Well aware of his in-laws’ disdain—Susan Pell’s will had already blocked him from receiving any control of Eleanor’s eventual inheritance—Harris had taken matters into his own hands.

At first, Eleanor tried to sue for custody. But she fled to America when it became clear that the London trial would involve her husband, who was acting as his own counsel, accusing her of infidelity on the stand. Citing child abandonment, Harris unsuccessfully attempted to block her from ever seeing Livingston again. And in early 1888, Eleanor capitulated.

"He told me my child was ill, and it wrung my heart so that I would submit to his terms," the New York Times reported Eleanor saying years later.

In exchange for joint custody of their son, Eleanor agreed to pay her husband $38,000 a year for the rest of his life, whether they were living together or not. (Today, that amount equals roughly a million dollars a year—out of an estate that today would be worth $206 million.)

Harris drew up the contract himself. In a particularly winning clause, he wrote that each parent was to pay half of any effort to regain their son if he were kidnapped again—up to a certain sum.

Yet for the next twenty years, the Phelps family apparently lived together in perfect amity, dividing their time between fashionable Paris houses—where they entertained royalty and nobility—and the Pau chateau.

And then, in 1910, Eleanor stopped paying.

It’s unclear why, after having forgiven—or at least acquiesced to—so much, Eleanor finally reached a breaking point. It might have been Harris’s manipulative treatment of Livingston, whom he’d gone to ridiculous lengths to prevent from joining the American Diplomatic Service (even sending a letter to President Taft). Or maybe the decades of slights had simply, finally eroded her ability to bend.

Harris sued; Eleanor sued back, having already filed for divorce. At last, her side of the story came out: that her husband had kidnapped their son to coerce her; that once he gained control of her money he took it all, leaving her only $12 a week; that he had stolen her mother’s jewels; that he was physically as well as emotionally abusive.

Things might have become acrimonious indeed, but the divorce never went to trial. Livingston, then a 25-year-old Harvard graduate in training with the diplomatic corps, persuaded his parents to mend fences yet again. In 1912, a new agreement was drawn up: Harris was to receive a generous yearly stipend from the family properties in New York, with the rest going to Livingston.

Scarcely a year later, 56-year-old Eleanor Phelps died in Paris of a stroke. Her son was by her side, and saw to her burial near her parents in Pau. Her husband is mentioned nowhere in the death certificate—nor in her will, which left everything to Livingston.

Beginning of the end

In 1915, Livingston married Red Cross worker Elizabeth de Berteux, the daughter of a French count, in Rome. World War I was nearing its one-year anniversary, but it seemed not to touch the young couple very much: They honeymooned in the U.S. and Europe, a much less protracted trip than Livingston's parents had taken decades before. Drawing from his inheritance what today would be $1.25 million a year, Livingston was also serving as the personal secretary to Italy’s American ambassador.

He had poorer luck when he was assigned to the embassy in St. Petersburg in 1917, the year of the Russian Revolution. Despite political tension, he and his wife stayed until diplomats were expelled the following year; frustrated and unhappy, Livingston quit the diplomatic service, the only job he’d ever hold.

It's likely Livingston and Elizabeth would have continued to live quietly (and quite comfortably) in Rome, had Harris not decided to sue them in 1921, demanding his son and daughter-in-law owed him $93,000 (about $1.27 million today) of lapsed payments from the yearly stipend agreed upon ten years before. Livingston sued in response, claiming his father still unlawfully held $150,000 ($2 million) worth of his mother’s jewels.

The lawsuits’ outcome is unclear, but Livingston likely conceded. Elizabeth died that October, and Livingston didn't seem the kind of widower to vent his grief in a bitter legal battle with his own father.

Harris Phelps died in 1929 at 84, reaching a greater age than either his wife or son ever did. He left everything to Livingston: a Paris mansion, which Livingston later lost; the estate principal, which Livingston was prohibited from accessing; and his meticulously catalogued library, including the honeymoon albums, which Livingston treasured for the rest of his life.

Chasing shadows

“I like that,” Jeb Bishop says quietly when I tell him how Livingston, in his late sixties, spent several years writing across the ocean to the National Geographic Society, anxiously pressing them to accept the photo albums by which he hoped his parents would be remembered.

Bishop—full name James Duane Pell Bishop III—is Eleanor’s first cousin four times removed. A web developer in Washington, D.C., he’s also an ardent genealogist. Hearing oft-conflicting stories of his grandfather’s “good old days” inspired his decade-long documentation of family lore.

“I just wanted to try to get the straight scoop,” he says. “I like to get at the truth, to see the structure.”

It’s not hard to imagine Livingston, Bishop’s distant cousin, doing the same: sifting through what his parents left him, pictures from their lives before him, looking for something. Did they love each other? Were they ever happy together? Like Bishop, trying to solve a puzzle; like us, trying to lay a hand on the immense, nearly physical history just beneath what we can see, a deep well of experience we can’t ever reach or relive.

Livingston Phelps died of heart failure in Switzerland, on April 13, 1960, 47 years to the day after his beloved mother. He’d survived two world wars, the Great Depression, and the loss of his entire immediate family. A library in Geneva where he’d found solace during World War II was the sole beneficiary of his will: They received journals and correspondence, and possibly the entire amount of the $125,000 estate ($1 million today), all that remained of the fortune that had caused his family such strife.

Childless and undistinguished, Livingston might have disappeared into history—and his parents’ memory with him—but for the photographs they left behind.

“It’s magical, that kind of time warp,” Bishop says. “We’re peering back at a shadow.”