Why walking safaris are the best way to see wildlife

Go on foot in Zambia’s South Luangwa National Park to encounter elephants, big cats, and spectacular habitats.

THE GO-AWAY BIRD is southern Africa’s pompadour-crested alarm clock from hell. Qwah...qwah...qwah! it calls, pestering me into consciousness. Qwah! Time to move!

Across the river I see three elephants foraging near the bank. Following their matriarch, they trundle along in descending order of height, munching on tufts of grass, their backs covered in a protective layer of dirt. Even at a distance, they appear large; even in their lumbering realness, they seem imagined. Being on safari is a dream, I think, and for a few moments, I’m not sure I’m awake.

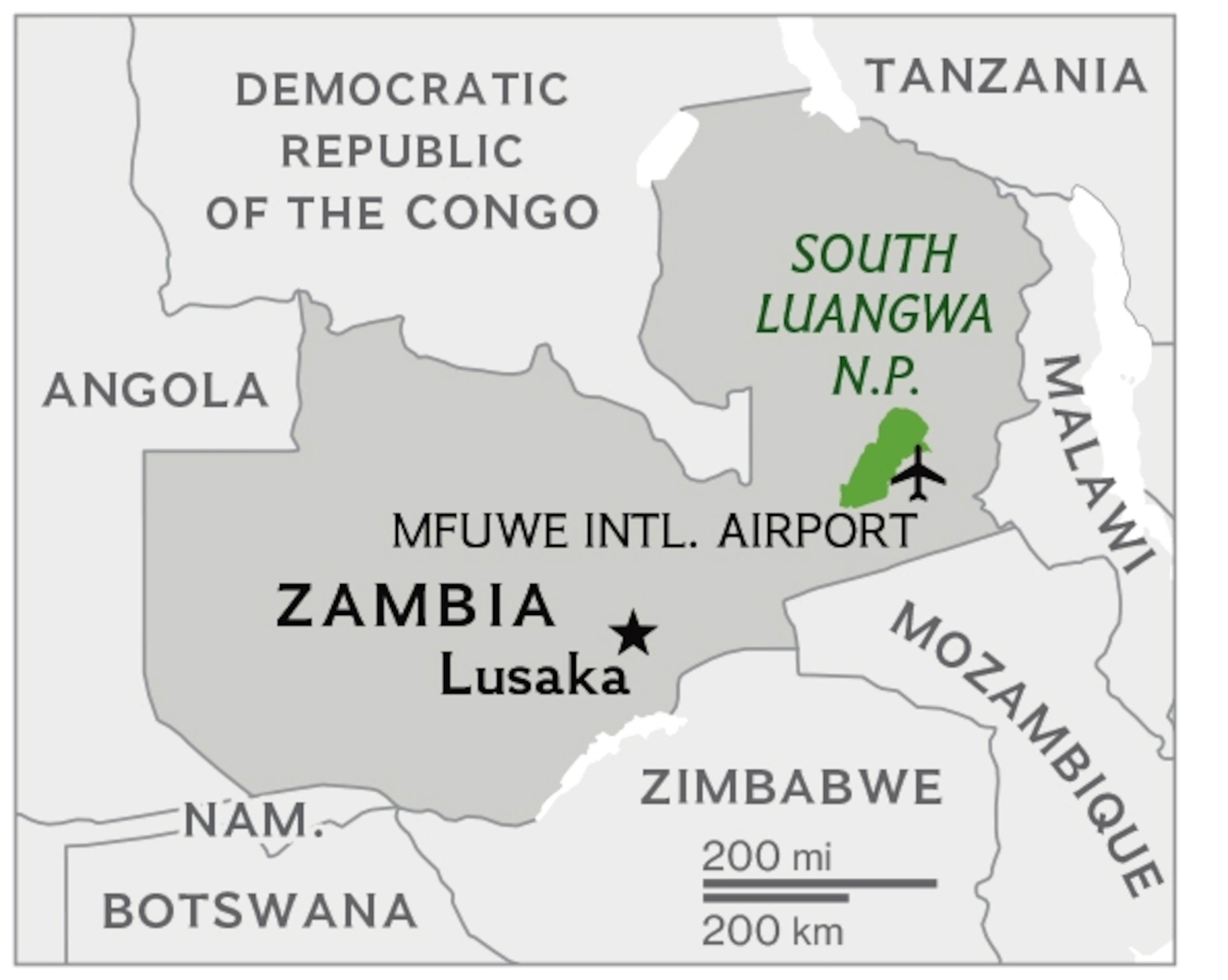

For safari-goers, the nearly 3,500-square-mile woodland savanna of South Luangwa National Park in eastern Zambia is a connoisseur’s secret, an animal lover’s destination. I’m staying at Zungulila, one of six camps near the Luangwa River managed by The Bushcamp Company, a National Geographic Unique Lodge of the World.

I have come to walk with the animals, to learn about the wild world from the dirt up, instead of the Land Rover down. Strange though it may seem, the idea of a walking safari was not a natural evolution but an introduced practice, pioneered half a century ago by game rangers and conservationists who sought to inspire a new ethic of engagement with the environment in Africa. On a walking safari, a human is briefly compelled to become an animal again, to relinquish dominance and sample vulnerability. (Read more on how to take a solo safari in South Africa.)

EVERYTHING IS BIGGER when you’re on the ground. I’m at the confluence of the Luangwa and Kapamba Rivers, and grasses that looked like fronds from afar turn out to be shoulder-high thorn walls. I’m following guide Kelvin Zulu on an afternoon walk beside the river. We’re trailed by Zambia Wildlife Authority scout Isiah Mvula. We investigate a towering termite mound and spot a lion’s paw print, the circumference of a cabbage, disrupting the sand. Kelvin is “reading the dirt” when a scampering waterbuck rustles the bushes. I shiver and get goose bumps. Suddenly I feel naked standing on the soil, exposed in my foolish attempts to achieve invisibility by wearing green clothing. The survival tools I’ve packed—sunblock, hand sanitizer, and a cell phone (there is no reception here)—reveal me to be a creature of the modern world, a person whose inclinations are to subdue, not embrace, the wild. And yet here I am, listening, observing, walking—with each step returning to the land, sensing the space around me, and sending warthogs dashing into the underbrush.

“Fresh leopard prints,” says Kelvin, who has been describing the particulars of paws. Hyena prints are splayed and meaty; African wild dog prints are squarish and tidy; baboon prints look like a small human hand with an extra palm. Safaris are ritualized meanderings, circular quests in which a question leads to an answer, which leads to another question, and so on. Every detail, from a broken branch to a birdcall, is part of a larger story that makes sense when told the right way. That’s what the guides do. They collect the clues, unravel the mysteries, and weave the narrative. The best guides elucidate; they don’t romanticize. The beauty of discovering the wild is not that its mysteries are inexplicable; it’s that its truths are comprehensible. On safari, curiosity is rewarded.

Kelvin plucks a tiny, waxy tube from the trunk of a mopani tree. It’s a portal into a hive of the minuscule stingless bee. “You can have honey without the sting,” he says. “Just not much honey.” Now 34, Kelvin has been fixated on wildlife since he was a child and was nearly trampled to death by an elephant when he was collecting water at the river. While growing up in Mfuwe, the village at the park’s gate, he became chairman of his school’s conservation club and a defender of wildlife even when elephants tramped and devoured valuable crops. (Meet the conservationists trying to save the Okavango Delta.)

BACK IN THE TRUCK, returning to camp, we spot a leopard in a tree, chomping on a baboon. We drive close and snap pictures. South Luangwa is one of the world’s top spots for viewing leopards, and this one knows it. He’s unbothered and proud and lazy enough to be falling asleep before our eyes.

As sunset nears, the land exhales with the cough of water buffalo, ticking toads, and an elephant’s trumpet in the distance. It’s as if all the Earth is slowly venting heat. We return to camp on the trail of a honey badger, and I see that the marsh below is filled with grazing impalas. It occurs to me that not every animal that sees tonight’s moon will see tomorrow’s sun.

That night a lion walks past my tent. A deep, vibrato lament rolling down the river wakes me up. As the call increases in volume, it is accompanied by the crunch of dry leaves. The lion approaches my tent and moans on the opposite side of a gauzy screen, 10 feet from my head. The call grows fainter as the beast creeps away along the riverbank, a shadow in the moonlight, its call a carnivorous Doppler effect. I fall asleep despite the fear of becoming a lion’s midnight snack.

A pink sun rises, and I find Kelvin beside a campfire as the Kapamba River reemerges from its dark night. I ask about the lion, who turns out to have a colorful history. Cassius and his partner, Brutus, were dominant males who banded together to control their territory and increase and protect their prides. The lions had been named by the human population and respected for their control of a vast area. But then one day Brutus disappeared, the coalition frayed, and Cassius walked alone. When Brutus reappeared months later, he’d lost his mane, he was gaunt, and his hip seemed to be dislocated. The solitary lions turned to smaller game, even scavenging like hyenas. This downfall set the stage for a new pair of lions to steal their territory, a challenge now under way. When Cassius walked past my tent at night, he was calling out—for Brutus, perhaps, or to let the usurpers know that he would not go down without a fight.

It occurs to me that not every animal that sees tonight’s moon will see tomorrow’s sun.

On our game drive, malachite king fishers dive into the water, and lilac-breasted rollers and white-fronted bee-eaters dart near the dun-colored bank. We hop out of the truck near a pod of grunting hippos filing into the river and meet a team of ecologists working with the Zambia Wildlife Authority to monitor the park. I’m reminded that a safari is not just a sensory experience but a social experience as well. To study animals on safari is to discover their interactions within their species, beyond their species, within their environment, and in relation to all the factors that influence their lives, including the human communities living on the perimeter of the parkland.

BIG RICH BOUTIQUE is the name of a shop in Mfuwe. On a drive through town we see tables piled high with potatoes and mobile phone recharging stands, and the words “God Gives” on the wall of Project Luangwa, a community development organization.

Kelvin shows me a school where classrooms have been funded by guests of The Bushcamp Company. On a desk I find a notebook a student left behind. I read this curious set of sentences written in blue ink, translated from a Bantu language to English: “How good and pleasant it is for people to live happily together.” “The day of judgment will surely come without fail.” And finally, “Only mad people can demand total freedom.”

Commitments to conservation and community are central to the mission of The Bushcamp Company, and I learn about a lunch program that feeds 2,500 students each day. I pump clean water from one of 17 Bushcamp-sponsored boreholes drilled in 2017, which eliminate the need for locals to make risky runs to croc-infested rivers. “About 15 years ago there were no roads here,” explained Andy Hogg, a native Zambian who founded the company. “But our business is part of a larger ecosystem that must support the human population.”

ON MY LAST MORNING the sun radiates an angry orange over the Kapamba River. We trail a pack of African wild dogs crossing the water and find a lioness tearing into a zebra while her two cubs wait their turn and hyenas lurk in the grass. In the distance, a kettle of vultures circle in the sky. Kelvin steers the truck over a dry lagoon mottled with hippo prints to get closer. The vultures swoop down to nip and peck at a massive carcass. The air is rank and moist. We study the mound. We are puzzled. And then we realize.

Of all safari sightings, we had tracked down the worst: a poached elephant, eviscerated, butchered of its meat, trunk removed, tusks torn out, exposed rib cage buzzing with insects. Near the elephant is an ashy camp fire, still warm from the night before, along with a rifle-cleaning brush and a heavy wood stake intended for transporting flesh. There is no ivory in sight.

Kelvin estimates that the elephant would have been about 40 years old. Its tusks would be worth about $200 when introduced to the illegal market (ivory increases in value through subsequent exchange). The elephant’s meat would be worth more than its ivory at the local level. It would have taken 10 men to carry the meat and tusks. Safari is about death as well as life. Animals sometimes eat each other to survive. This is the circle of life. But what I saw that day isn’t a necessary part of that pattern, and it will be a long time before I digest it.

Elephant populations in South Luangwa National Park are possibly increasing according to the Great Elephant Census research project; poaching is uncommon here. But in other parts of Zambia, including along the border with Angola and Namibia, populations are declining, an echo of the declared extinction of Zambia’s rhinos in 1993. The loss of wildlife threatens communities supported by the safari industry. But living with animals isn’t a walk in the park. They can devour crops and trample villages. I recalled an earlier conversation I had with Kelvin. We discussed the economy of elephants, comparing their value as tourist attractions, as hunters’ trophies, and as contraband. For Kelvin, the question of how to assess the value of an elephant is related to what will improve the lives of people in Mfuwe. “Through tourism, a living elephant benefits more people over its lifetime,” he said, “but it’s not so easy when people are depending on you to provide for them.” (Learn how tourism helps elephants make a home.)

A bushcamp tradition awaits: sundowners at the river. Not beside the river or near the river, but in the river. Chairs are lined atop a sandbar in the middle of the Kapamba, a card table serves as a makeshift bar, and popcorn explodes from a pan on the fire. To the crocs, we probably look like Kardashians. Noisy, possibly tasty, but not worth the effort.

Back at camp, we discover an unexpected visitor. Brutus has returned, limping along the bank. His mane is growing back, and his proximity suggests that he’s either wise or desperate, so we keep our distance. That night Brutus sleeps in the camp. Being on safari is a dream, I think, and I fall asleep too.