Sometimes a portal isn’t a door. It’s a bowl of soup.

Raise a spoonful of tom kha kai, a traditional Laotian coconut chicken soup, to your lips, and a tantalizing perfume of lemongrass, lime, and galangal wafts upward. Its scent is sublime and earthy, hot and sour. The fragrant plume comes with a peppery kick. The sensation is vivid, somehow poignant, and utterly transporting.

The memory brings a smile as I stand in a line of passengers at Louangphabang airport, in the Lao People’s Democratic Republic. I’ve traveled 9,000 miles to Southeast Asia inspired by Van Nolintha, a charismatic 32-year-old Laotian-American restaurateur in Raleigh, North Carolina, whose inventive renditions of his childhood dishes from his native land have earned the acclaim of diners and food critics alike.

Now I’ve come for a taste of the real thing. Upon leaving the airport, my first views of Laos are the Phou Thao and Phou Nang mountain ranges, which surround the ancient royal city of Louangphabang like an embrace. The slopes are lush with trees that comb and catch the low-lying clouds. As I enter the city, a cluster of motorbikes overtakes my taxi, trailing fumes and impatience. A teenage girl, sitting sidesaddle in a Laotian silk tube skirt called a sinh, flashes past. Her face is inches from her smartphone. She’s texting furiously, oblivious to her young driver and the pushy traffic puddling up behind us, which includes four Toyota vans packed with Chinese tourists. Their wide-brimmed sun hats curl against the steamy windows. (Read about the water buffalo dairy farm making waves in Louangphabang.)

Built on a peninsula formed by the confluence of the Nam Khan and Mekong rivers, the city was once an important Buddhist religious center and seat of empire. From the 14th to the 16th centuries, it served as the capital of a state that called itself Lan Xang, or Kingdom of a Million Elephants. Princely wars and declining fortunes followed. In 1560 the Laotian capital was moved to Vientiane, though Louangphabang retained its own king. Eventually Laos fell into European possession following the creation of the French protectorate in 1893. The French recognized Louangphabang as the Laotian royal seat once more. Beside the ancient temples, a new Parisian-designed palace and French administrative buildings filled the historic core, now a UNESCO World Heritage site.

I locate my friend Van at Satri House, a former colonial mansion revived as a boutique hotel. He’s in the courtyard, dangling his legs in the pool. “Do you like it here?” he asks as a bottle of chilled rosé appears. I do. Furnished with antiques, the 28-room property exudes serenity and lost grandeur. As if on cue, a buttercream-colored Rolls-Royce glides past on the street beyond, with an elegant, white-haired Laotian woman seated in back. Who is she? Where is she going? There are mysteries in Louangphabang. And, I come to learn, ghosts.

“My grandmother was named Mae Tao,” Van tells me. “Growing up in Louangphabang, I tended the family flower garden with her. She taught me that each flower had a life and personality, and how to cut, clean, and arrange each bloom in a certain manner,” he says. “ ‘You are from Louangphabang,’ she liked to say. ‘You should care about small details—they’re sacred.’ ”

That attention to the little things would sustain Van, who grew up in this neighborhood, in a small house in another time in a different Laos. The years following the American War (the Laotian term for the Vietnam War) brought turmoil to Louangphabang. In 1975 the monarchy was overthrown, and Laos became a communist state.

For Van’s family, the two decades following meant disruption, conflict, and hunger as Laos turned inward. He and his sister, Vanvisa, saw their parents struggle, but their hospitality was forever bountiful.

“We were so poor, but there was always someone visiting the house,” he tells me. “There were always people at the table.”

His parents fretted over their children’s future. Should they send them away for an education, into a world they barely knew? Should they keep them close to home and tradition? In 1998, at age 12, Van left for America, and his sister soon followed. He would not see his home in Louangphabang for six years.

In Greensboro, North Carolina, Van stayed with family friends and attended a public middle school. It was a difficult separation from all that he knew. He began cooking the food he remembered from Laos, determined not to forget the place he and his sister left behind. “I needed to make sure our memories of Louangphabang were preserved,” he says.

He listened to pop music and spoke English fluently, attended university in Raleigh on a scholarship, and studied design and chemistry. In 2004, like so many immigrants before them, Van and Vanvisa became U.S. citizens.

Food and family

The next day, Van invites me for breakfast in the heart of the historic district on Sakkaline Road. We sit down at a family-run, open-air restaurant across from a gilded temple where monks clad in marigold orange robes whitewash the walls. An iron pot full of a tangle of rice noodles bubbles away, heated by a wood fire. The owner welcomes us with big, broth-filled bowls and piles of fresh mint, basil, and lettuce leaves in a dozen shades of green. We spoon in jeow bong sauce—orange and scarlet and sweet and sour. Additional plates of sticky rice, bean sprouts, limes, and long beans, as well as small bowls of fish sauce and fermented shrimp paste, crowd the table. The bounty finds its way into our bowls. All is simple, yet with a complexity of flavor.

“Identity is in the very food you eat here,” Van says. “It’s profoundly important to Louangphabang. Our cuisine is central to how we understand ourselves. Our sense of place and relationship to the sacred are found in the ingredients we harvest along the river and the food we cook at home.”

What happens when you can no longer experience the food that so defines you, I wonder, knowing that with suitcases and ambitions, each wave of newcomers to U.S. shores brings memories and yearnings for a taste of home. According to a study by the National Restaurant Association, the top three global cuisines eaten in America—Chinese, Mexican, and Italian—are scarcely considered foreign anymore, as nine out of 10 Americans eat them. But only 20 percent of Americans have sampled cuisines such as Korean, Ethiopian, and Brazilian. Laotian food is so uncommon it didn’t even make the list, but for Van and Vanvisa, it became their meal ticket. “How you tend your land is how you honor your family,” says Van, who made the difficult choice to sell a piece of ancestral land to finance their restaurant in Raleigh.

In 2012 he and his sister opened Bida Manda (Sanskrit for “father mother”) in a revitalized neighborhood around the corner from the city’s bus station. The mix of Laos and Dixie created a sensation. Last year, with co-owner and brewer Patrick Woodson, the siblings opened Bhavana, a craft brewery and community café that introduced Raleigh’s techies and Tar Heels to the piquancy of Laotian delicacies like mok pa—aromatic steamed fish in a banana-leaf wrap, spiced with coconut curry and served with sticky rice—and handcrafted ales brewed with mangoes and peppercorns. Purple hydrangeas from the house flower shop and art books from the house bookstore grace its interior, which fills out a light-washed, warehouse-size space. As his grandmother said, it was all in the details. “A showstopper,” proclaimed Bon Appétit. Soon after, Bhavana was nominated for a James Beard award, the Oscar of edibles.

The artful moment

A love for the small, artful moment infuses Louangphabang in unexpected ways. Walking on a side street in the old city, I notice plumeria blossoms set carefully and reverently atop fence posts and doorstops, as offerings to the Buddha, a reminder of the city’s respect for gesture and the fusion of earth and spirit. I spot the creamy white blooms on a hotel-room nightstand and on the steps leading to the temples. Plumerias become, for me, a sign not just of beauty but thoughtfulness.

At the base of Louangphabang’s sacred Mount Phousi, I come across vendors selling songbirds in wicker cages. I learn that locals release them at the summit in front of the gilded wat, or temple, to receive good luck. It’s a beautiful gesture—one that glosses over the seeming cruelty to a trafficked species.

A tour of the former Royal Palace illustrates another of Louangphabang’s traits: accommodation. The French commissioned this 1904 beaux arts pile for the Laotian king and paired it with local motifs such as the three-headed white elephant beneath a white parasol, the symbol of the monarchy, set in the pediment above the entrance. The throne room is decorated with mosaics of warriors and elephants in mirrored glass, arranged like refrigerator magnets on its scarlet walls.

I walk outside, past the tent sheltering a golden barge, and find something surprising in the royal garage: a white 1958 Ford Edsel, a gift from the U.S. government, awaiting a chauffeur who would never come. In 1975 the communists ordered the king’s family to reeducation camps—ending a 600-year-old lineage—and turned the home into a museum.

The sun in Louangphabang can be fierce. In the afternoon, darkened rooms and overhead fans soothe both travelers and geckos—the former seeking gin, the latter insects. In late afternoon, as the heat begins to cool, vendors arrive with their goods at the Night Market. I snake through their stands to the Mekong. By the time the cotton and silk scarves, embroidered textiles, silver bangles, and Beerlao T-shirts are unpacked and enticingly displayed, the sky has turned from lemon to a deepening indigo, and I am waiting for Van by the river. (Discover the Mekong through colorful illustrations.)

He has rented a long, slender riverboat and invited a group of his friends aboard for an early evening cruise. He takes care of all the specifics. Staff offer amuse-bouches while we float downstream in the gathering twilight, watching the fishermen in their boats and admiring the vine-covered cliffs. The sky is soft, and Van’s friends grow quiet. The only noise is our motorboat sluicing through caramel water.

I imagine journeys from an earlier time, when the riverbanks were crowded with great jets of bamboo and towering teak and giant palms interspersed with cassia, rhododendrons, and catalpas, all of it dripping with orchids. The foliage hid tigers and rhinos—and also sapphires, copper, and gold, which floated down with the current to Louangphabang to trade to the larger world.

“The Mekong is the heart of Laotian spirituality. It’s both Laos’s bloodline and livelihood,” Van says. “My grandmother’s and grandfather’s ashes were spread in Mother Kong, where their memories, hopes, and stories are kept.”

As romantic and enigmatic as it is, Louangphabang is also part of the in-your-face 21st century. It is only becoming more intertwined with the wider world. The hammer and sickle still flutter from government buildings, and while citizens joke that the acronym for the People’s Democratic Republic stands for “Please Don’t Rush,” Laos is doing just that. Development has thinned those once exuberant forests, and the knotty jungle is being replaced by ordered rows of teak. The former Kingdom of a Million Elephants counts only a few hundred of them now.

Early one morning, in a park at the promontory where the rivers meet, I pause to admire the dawn, only to jump with alarm as a megaphone erupts in Mandarin to beckon clattering Chinese visitors to assemble beneath a guide’s flag. Tourist numbers are growing. Not just from China but from all over the world. Already foreigners outnumber locals at the traditional dawn alms-giving ceremony for the monks. Old, ornate, and delicate, Louangphabang must guard against overtourism or else crumple under the invasion.

So I think the Nolinthas’ effort to establish Louangphabang’s culinary traditions in Raleigh is important. It was daring to trade a plot of land in Laos for a promise of success in the United States. The last time I spoke with Van, I told him I worried about his old home. But he reassured me that the city’s spirit is less fragile than it might appear at first.

“I’m uncertain of what Louangphabang will become,” he said. “But whatever happens, the city will always be a portrait of generosity, grace, and beauty. Guests will always be welcome at our table. After all, that is our way.”

What to know

Flying into Louangphabang is easy with daily, direct service from Bangkok and Hanoi. A tourist visa is required. For Americans, visas are furnished on arrival for $35 cash; bring two passport-size photos.

Not to miss

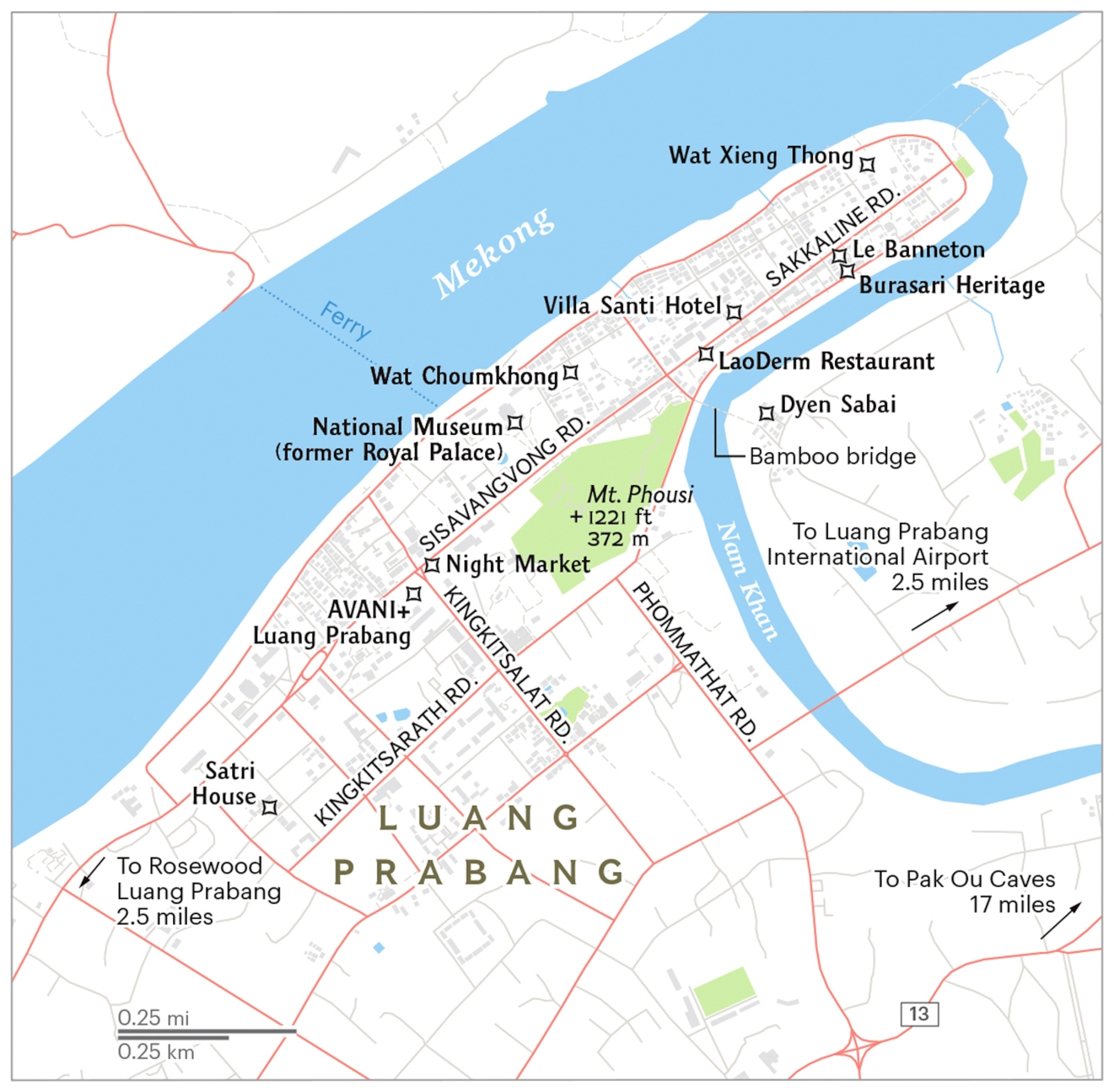

National Museum: Built in 1904, this palace museum offers a glimpse into the world of Laotian kings and their families. On the grounds: an opulent pavilion housing the Prabang Buddha and a garage holding mid-century American cars, gifts from the United States.

Night Market: Down the street from the former palace, sellers at the Night Market display both authentic Laotian crafts, such as woven silk, embroidered textiles, and silver jewelry, as well as made-in-China offerings of Beerlao T-shirts and knockoff cotton scarves.

Wat Xieng Thong: Known as the Golden City Temple, this 16th-century complex was built near the meeting of Louangphabang’s two rivers and is important as a religious and national symbol. It was here that Laotian kings were crowned.

Mount Phousi: The energetic can brave the humidity to climb the hill’s 300-plus steps for a spectacular view of the city and its surroundings. A small 200-year-old stupa, or temple, sits atop the summit.

Where to eat

Le Banneton Café: This Paris-inspired boulangerie offers dark, rich coffee plus freshly baked pastries, baguettes, and croissants, a tradition from the French colonials.

Dyen Sabai: You need to cross the Nam Khan on a bamboo footbridge to get to this casual restaurant, but the trek is worth it for the river views, floor-pillow seating, and pork with fried eggplant.

LaoDerm Restaurant: Near where Sisavangvong becomes Sakkaline Road, LaoDerm serves Laotian comfort food—everything from crunchy, spicy som tam (green papaya salad) to crickets deep-fried with lime leaves and tossed with salt.

Where to stay

AVANI+ Luang Prabang: Sleek and chic, this five-star hotel built around a large pool affords easy access to the Night Market, located just across the street. minorhotels.com/en/avani/luang-prabang

Rosewood Luang Prabang: The Rosewood sits a bit out of town but pampers with a waterfall, an indulgent spa, and wellness programs.

Satri House: The antique-filled rooms, whitewashed walls, and reflecting pools accented with lotus blossoms evoke French Indochina.

Villa Santi: This boutique hotel housed in a French colonial villa has a prime location in the World Heritage district.