In late summer, Napa Valley was forced to confront a harsh reality: Harvest season in this world-famous wine region is now also fire season.

The unprecedented fire events of 2020 have left little doubt that California’s wine country has entered a new, dangerous era. First, in August, came a lightning siege that sparked fires throughout the state. One of the lightning strikes touched down in Napa. The resulting fire would ultimately grow to over 360,000 acres, resulting in five deaths.

Then, in late September, a separate blaze known as the Glass Fire erupted in Napa Valley. It would soon become the most destructive wildfire in the history of this valley—worse, even, than the record-setting fires of 2017. This time, 1,235 buildings have been destroyed, including nearly 300 homes.

Northern Napa Valley, reliably verdant and lush at this time of year, became an eerie landscape of charred earth and white ash. Grapevines were blackened, wineries reduced to rubble.

Napa is America’s most celebrated and important wine region, the figurehead of California’s $40 billion statewide industry. But the disasters of 2020, compounded by the serial devastation of recent years, have thrown it into existential crisis. Climate change, which was already threatening to alter the taste of Napa’s prized Cabernet Sauvignons, is now fueling fires that seem to turn more destructive each time.

(Related: Witness California’s record blazes through the eyes of frontline firefighters.)

The implications ripple through every facet of life here. The perennial presence of wildfire threatens the farmworkers who must choose whether to work in oppressively smoky air or not work at all. It imperils the local economies of wine country’s towns, which have grown heavily dependent on tourism—to the tune of $2.23 billion in visitor spending in a typical Napa Valley year. And it endangers the viability of the wine itself: By one estimate, complications from fire and smoke may prevent as much as 80 percent of Napa Valley’s 2020 Cabernet Sauvignon grapes being made into wine.

Wildfire, in California wine country, has the power to destroy not only buildings—but also the region’s economic and cultural fabric.

Road to recovery

Less than 24 hours after the Glass Fire exploded, one of Napa Valley’s grandest wineries could be seen engulfed in flames. The hand-quarried stone winery of Château Boswell, located on the storied Silverado Trail, was decimated.

“All my personal possessions were lost,” says owner Susan Boswell, “but most importantly my family history,” including the first bottles of wine that her late husband had made in 1979. (Also gone, she added, were letters that her ancestor Aaron Burr had written to his wife Theodosia.)

From there, the fire moved relentlessly through the valley’s northern stretches, damaging structures on at least 26 wine and vineyard estates. Castello di Amorosa, a popular tourist hub modeled on a medieval Tuscan castle that took 15 years and $40 million to construct, saw one of its main buildings destroyed. Newton Vineyard, an ambitious property owned by luxury conglomerate Louis Vuitton Moët Hennessey that had just completed renovations a few weeks earlier, was in ruins.

But most of the Glass Fire’s devastation occurred at small-scale, family-run wine estates—names like Behrens, Sherwin, Hourglass, and Hunnicutt. Historic buildings dating to the mid-19th century at Burgess, Cain, and others went up in flames. Along with them went inventories of bottled wine, in some cases the entire production of multiple years.

Many vintners defied evacuation orders to stay behind and defend their properties by cutting fire lines with chainsaws, stashing propane tanks away from flames and dousing their buildings in water. They had one important helper. While Napa’s landscape is clearly fire-prone, it is also dotted with natural firebreaks: grapevines. As living plants, vines are standing wells of water and have consistently shown themselves capable of slowing the path of fire, sometimes even saving structures.

“The undergrowth, the native grass, is typically what burns,” says Chris Howell, winemaker at Cain Vineyard. “But by now, we know that the vines themselves don’t burn.”

Despite the extent of the losses, most of the 215 wineries located within Napa Valley’s evacuation zones were still standing by the time the Glass Fire was reaching a stable containment level, one week later—thanks to some unknowable equation of firefighting, vineyards, wind patterns and luck. But the hard questions were only starting to surface.

Keeping workers safe

One of those questions pertains to vineyard workers, a largely Latinx immigrant population that forms the backbone of California’s wine industry. The role of these workers is never more crucial than from August through October, when they pick the grapes that will ultimately become wine.

But picking grapes when the air is thick with wildfire smoke can be hazardous to the health of these workers, who already had to reckon with the risk of contracting COVID-19 on the job.

“The Latinx population sustains the local economy here, but there are very clear racialized disparities,” says Gabriel Machabanski, associate director of the Graton Day Labor Center, a community organization supporting immigrants in Sonoma County, to Napa’s west.

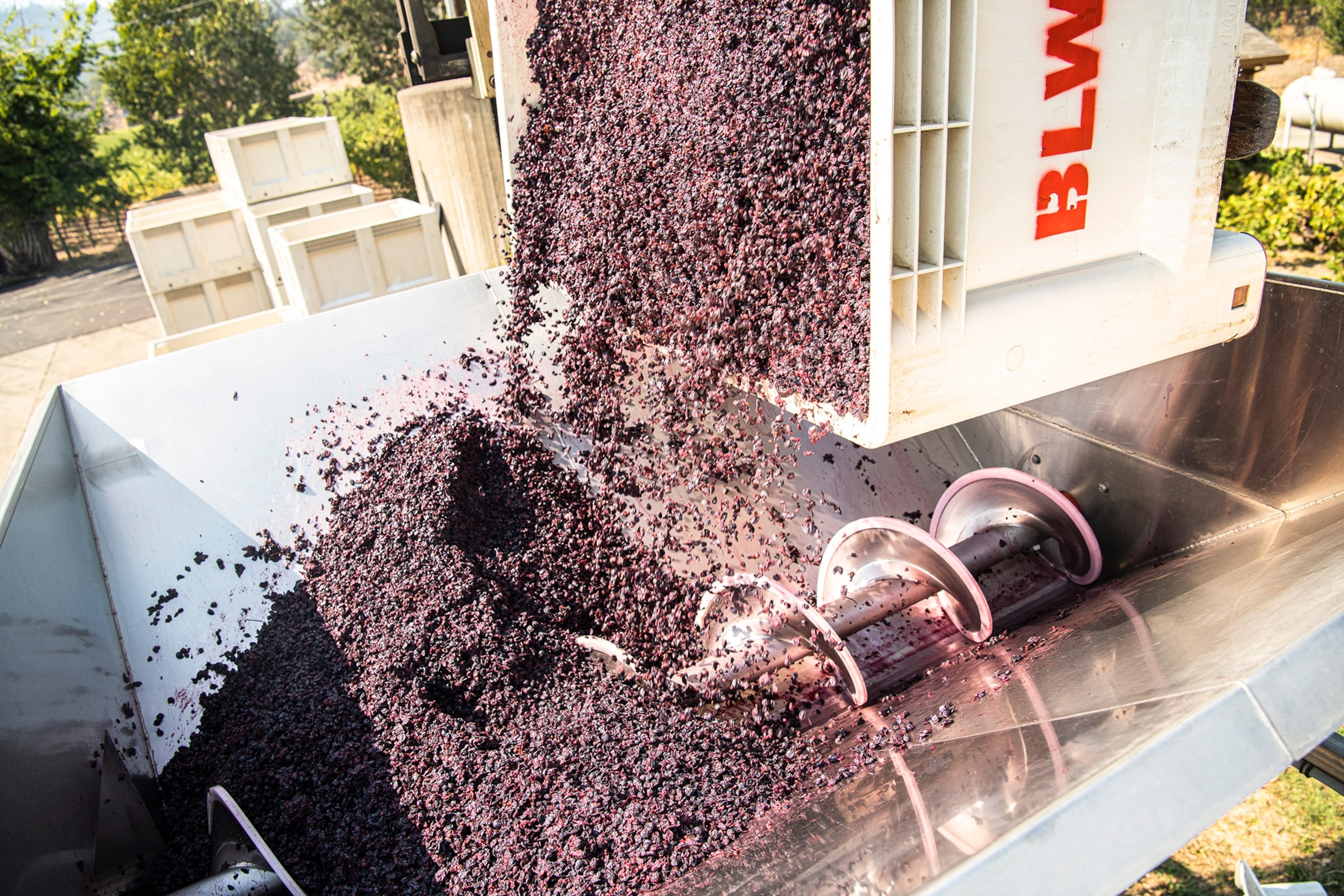

Many Napa and Sonoma wineries proceeded with the harvest despite the fires. In fact, the need to pick the grapes felt even more urgent for wine quality, to minimize the grapes’ exposure to outdoor smoke. That meant that some managers were sending farmworkers near active blazes.

(Related: Here’s how breathing in wildfire smoke affects the body.)

Businesses can request from the county agriculture commissioner what’s known as a Verification of Commercial Agricultural Activity, which can grant access into mandatory evacuation zones. (Ultimately, though, admission past an evacuation zone line is at the discretion of local police, not the agricultural commissioner.)

On October 6, Napa County had received 536 requests for these verifications, says commissioner Humberto Izquierdo, though he would not say how many of those had been approved. Sonoma County records show that of the 115 agricultural access verifications issued for the Glass Fire, 25 of them were requesting access for crews of 10 or more people.

“It was really revealing and concerning to hear that folks were working outside in evacuation zones where the air quality was significantly over 150 [AQI], and people were not getting N95 respirators,” Machabanski says. (As defined by the Environmental Protection Agency, 150 AQI is the threshold at which members of the general public may experience health effects.)

To him, that was evidence that “the local industry and local government is really prioritizing the health of their grapes, and salvaging their harvest, over the health of immigrant workers.”

For the workers, the situation presents an impossible choice: pick grapes in potentially unsafe conditions, or go without pay? Harvest can be lucrative: At the season’s peak, some of Napa’s highest-end vineyard management companies pay pickers as much as $45 an hour. But many agricultural workers in wine country are working only five to six months a year, says Machabanski. “Despite wages being consistent over a few months, if you take the average income over the course of a year for low-wage immigrant workers, most of them are living in poverty.”

(Related: Farmworkers risk coronavirus infection to keep the U.S. fed.)

If fire is indeed now a permanent fixture of harvest season, solutions—such as mandatory hazard pay—are needed to protect this vulnerable population both physically and financially. But finding those solutions has not yet proven to be a priority of either local governments or the industry.

Fires continue to rage

Perhaps the most sobering lesson of the 2020 fires is that California can no longer expect blazes to fall within a predictable time frame.

Fire season has historically come for wine country later in the fall: October, stretching into November. That’s meaningful because by that time of year, most wine grapes have been picked. When catastrophic fires spread across Napa and Sonoma counties in October 2017, for example, an estimated 90 to 95 percent of the region’s grapes were off the vine, safely fermenting inside wineries—and therefore no longer vulnerable to the pernicious effects of smoke.

(Related: What is the science connecting wildfires to climate change?)

That phenomenon, called smoke taint, occurs when wildfire smoke lingers in the air for an extensive period of time, imparting certain compounds into the skins of wine grapes. Nearly impossible to eradicate, these compounds result in unpleasantly smoky flavors and aromas in the finished wine; the sensation is often described as tasting like an ashtray.

This year, the lightning fires came in mid-August, when virtually none of California’s wine grapes had been harvested. What’s more, the staggering geographic spread of the lightning fires left few wine-producing areas of California untouched. Wine regions as disparate as Monterey and Mendocino, Sonoma and Santa Cruz, feared that their crops could be ruined.

Wineries rushed to send samples of their grapes and wine to laboratories that test for markers of smoke taint, but the high volume of submissions backlogged results from the leading Northern California analyst, ETS Laboratories, by more than a month. The delay almost guaranteed that the outcome would be useless. By the time winemakers found out whether grapes had been compromised, they’d be on their way to becoming raisins.

If some Napa vintners had been holding out hope that their fruit might have emerged from the August fire events smoke-free, September’s fire seemed to dash it all. “The crop’s not OK,” says Hal Barnett, owner of Barnett Family Vineyards, whose property on Napa’s Spring Mountain sustained damage to some buildings.

“There’s so much smoke that there’s no way we can make any wine this year. It’s not even worth testing,” he continues. “I don’t think there’s gonna be any Cabernet coming off Spring Mountain in the 2020 vintage.”

The Glass Fire is still smoldering, and the extent of smoke damage to Napa fruit—though undoubtedly large—remains unknown. For a county whose grape crop was valued at $1 billion in 2019, there’s a lot to lose.

But so far, vintners have had little recourse to prevent those losses. “I had become realistic about it,” said Barnett. “Like it was going to be a matter of when, not if.”

California-based photographer Stuart Palley—a qualified wildland firefighter who has photographed more than a hundred fires across the state—is documenting the devastating effects of the 2020 fires. Follow him on Twitter and Instagram.