1 of 13

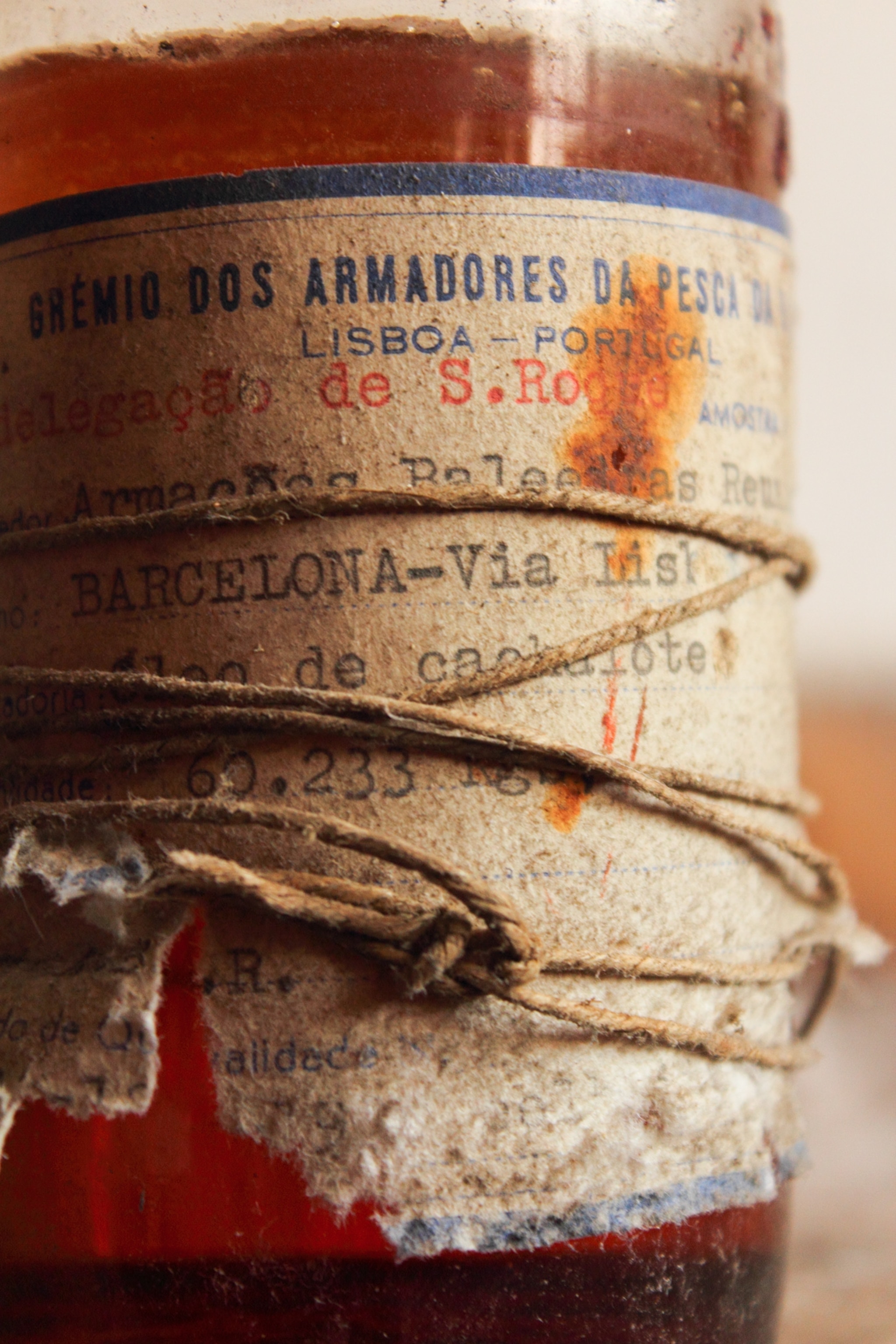

Photograph by Gemina Garland-Lewis

Pictures of Azorean Whalers: The Last of Their Kind

A National Geographic explorer has documented how Azorean whalers used 18th-century techniques to hunt sperm whales well into the 20th century.

June 13, 2013