Remembering Jane Goodall

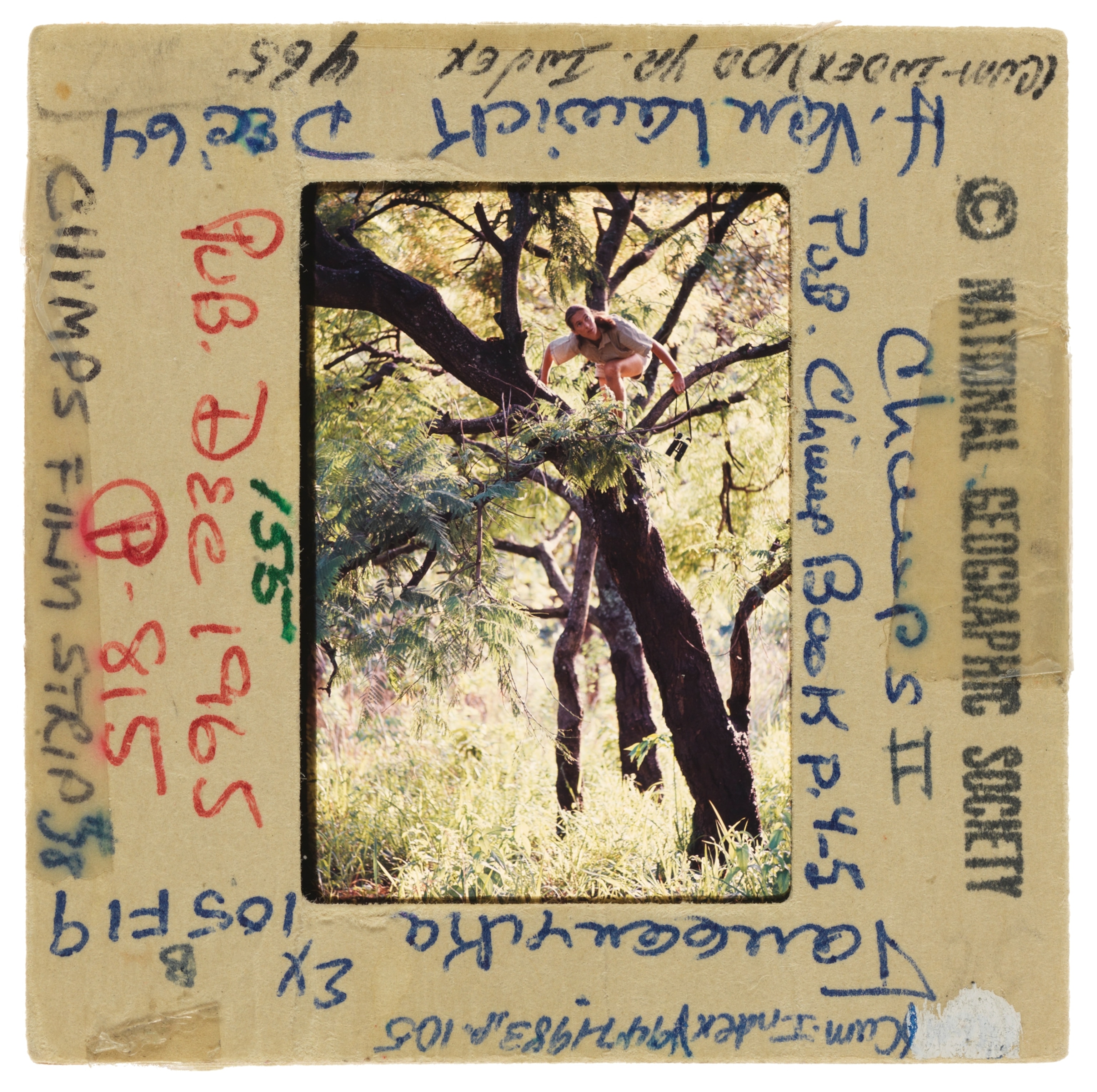

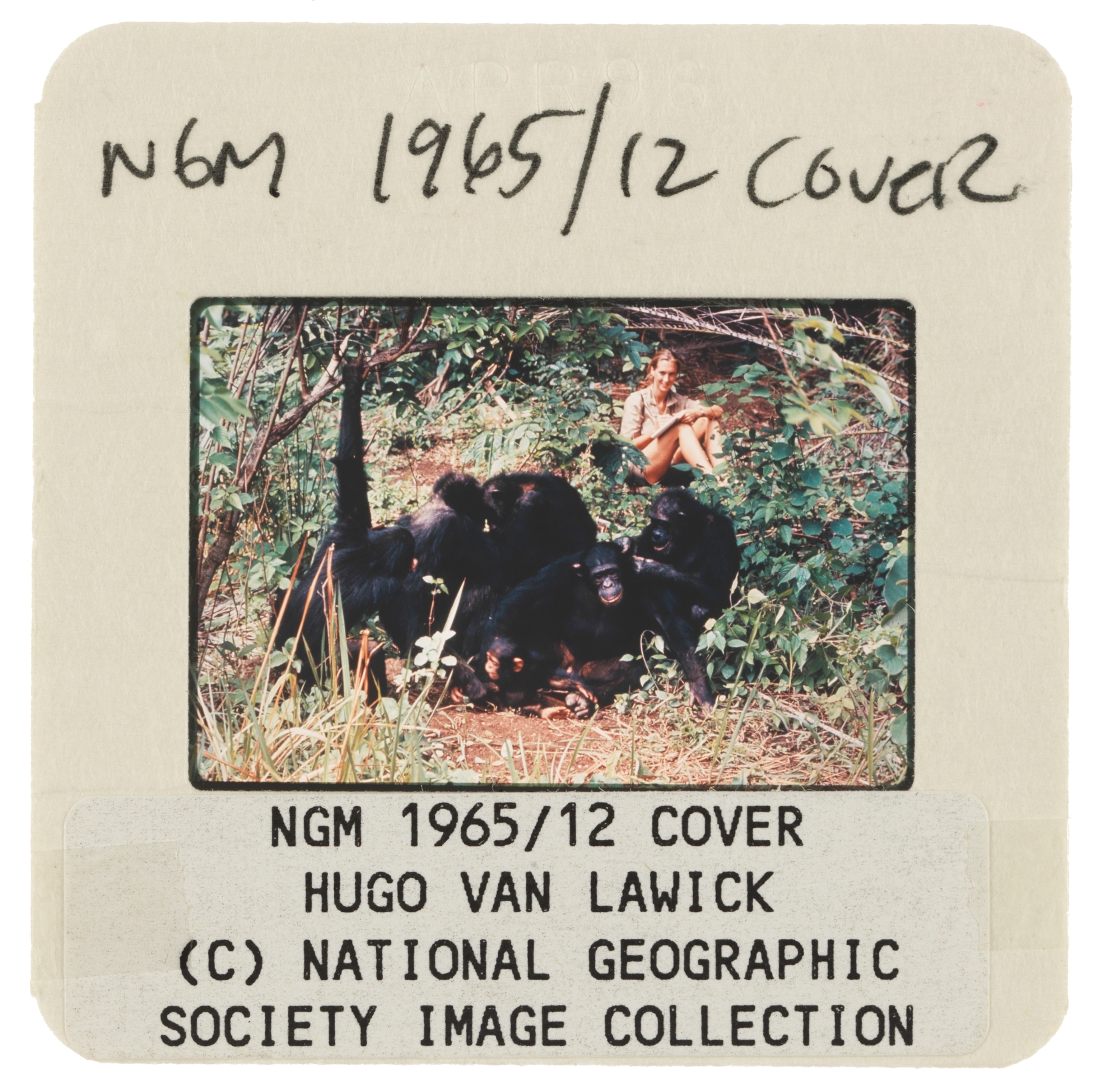

Few figures in history have done more to change our understanding of the natural world. We celebrate Jane Goodall’s remarkable life with rare images from the National Geographic archives.

Humans once stood on a pedestal: made by God in his image, earthly lords of all creation, categorically distinct from mere animals. That was the belief, anyway. Jane Goodall played a large role in eroding that self-flattering conviction, with her extraordinary study of wild chimpanzees at what is now Gombe National Park in Tanzania. By discovering unexpected behavioral similarities between chimps and humans, she continued the revolution begun by Copernicus and Galileo and advanced in a great leap by Charles Darwin: taking Earth out of the center of the universe and humans down from our holy isolation. Goodall helped us see, long before genome comparisons confirmed it, that the gap between chimps and people is smaller than anyone thought. Gorillas aren’t the closest living relatives of chimpanzees. We are.

She couldn’t live forever, though her impact will. Goodall’s life ended in October in Los Angeles, while she was on yet another speaking tour. Ever since 1986, when she chose to step away from her scientific role and become an activist, she had traveled, lectured to large crowds, made uncountable media appearances, called on political leaders, and met quietly with groups of children, all in an effort to change human hearts and human ideas—to bring people toward a gentler and more knowing relationship with the natural world. She was 91. In the days after her death, it was reported that she died of natural causes. That’s a vague phrase, carrying almost no meaning except that a person was old and that life is finite. It’s a little too negative. I think you could just as well say that she died of fulfillment.

In the long lifetime between her birth and her death, one date is paramount. On July 14, 1960, at age 26, she arrived by boat at Gombe, on the east shore of Lake Tanganyika, in what is now Tanzania, to begin her study of chimpanzees. At that time, the total population of chimps—which are endemic to equatorial Africa—was roughly a million. A mere hundred or so lived in the Gombe reserve. But maybe they could be taken as representative.

She was an improbable fit for the task. She had no qualifications in biology, no academic degree. Money had been short after her parents’ divorce, and in lieu of university, Goodall got herself practical training at a secretarial school. But she had impractical dreams—of working with wildlife, or perhaps as a journalist—and ferocious strengths, identified first by the eminent paleoanthropologist Louis Leakey, who hired her as his secretary in Nairobi, Kenya. Over time, she impressed him. He saw something more, and he offered her a new challenge. He wanted some insights on chimpanzee ethology because he thought that might illuminate human ancestry.

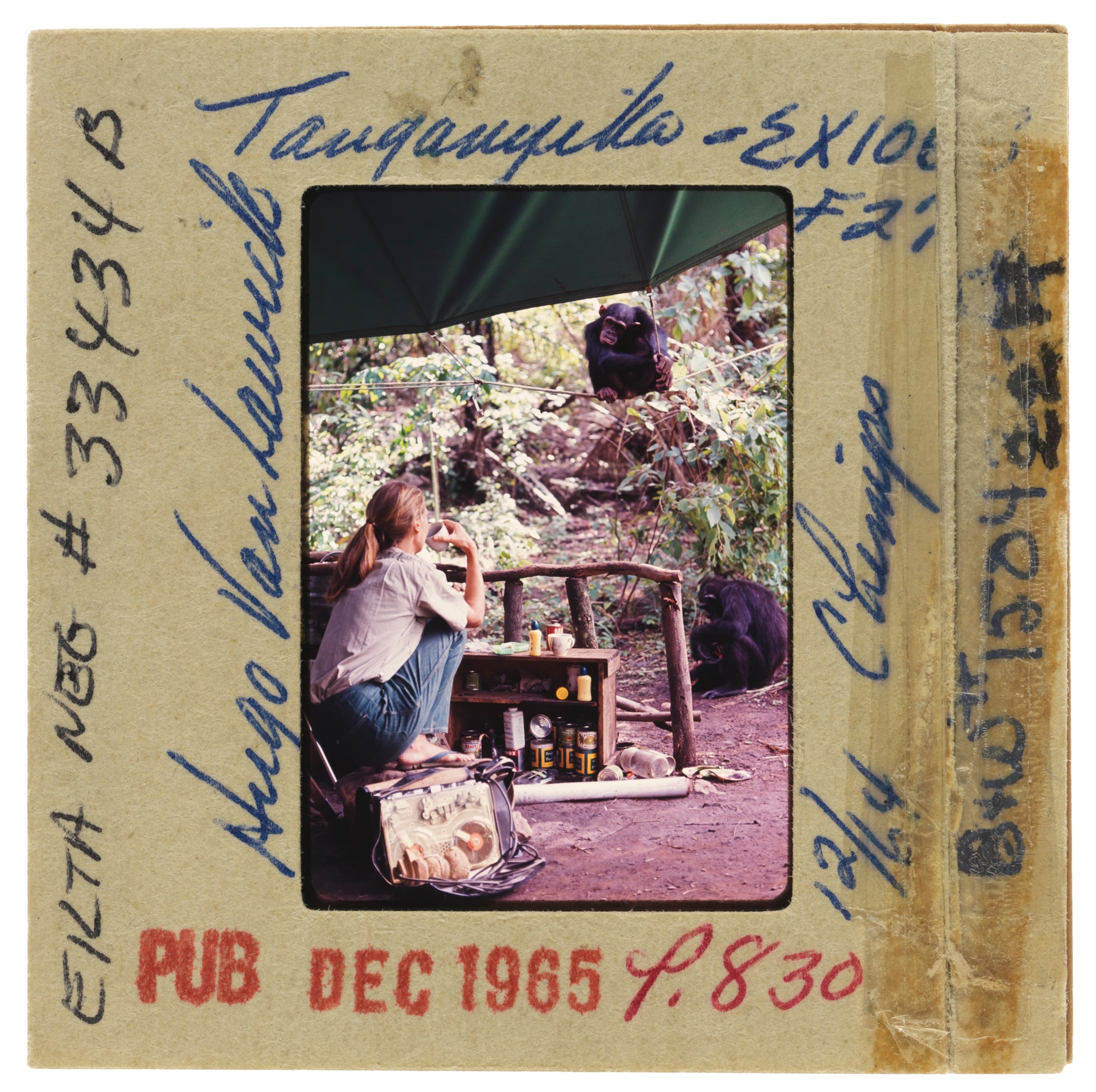

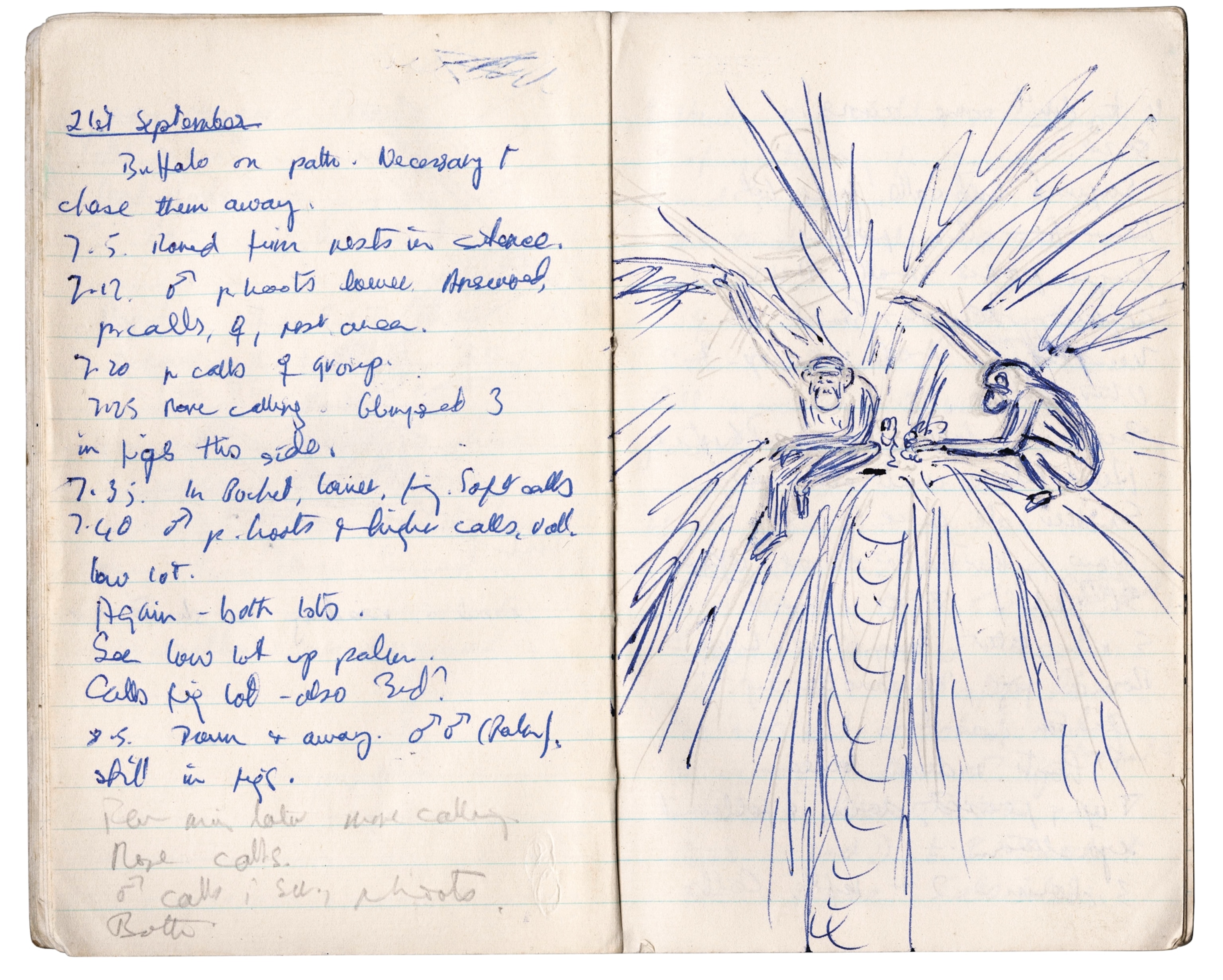

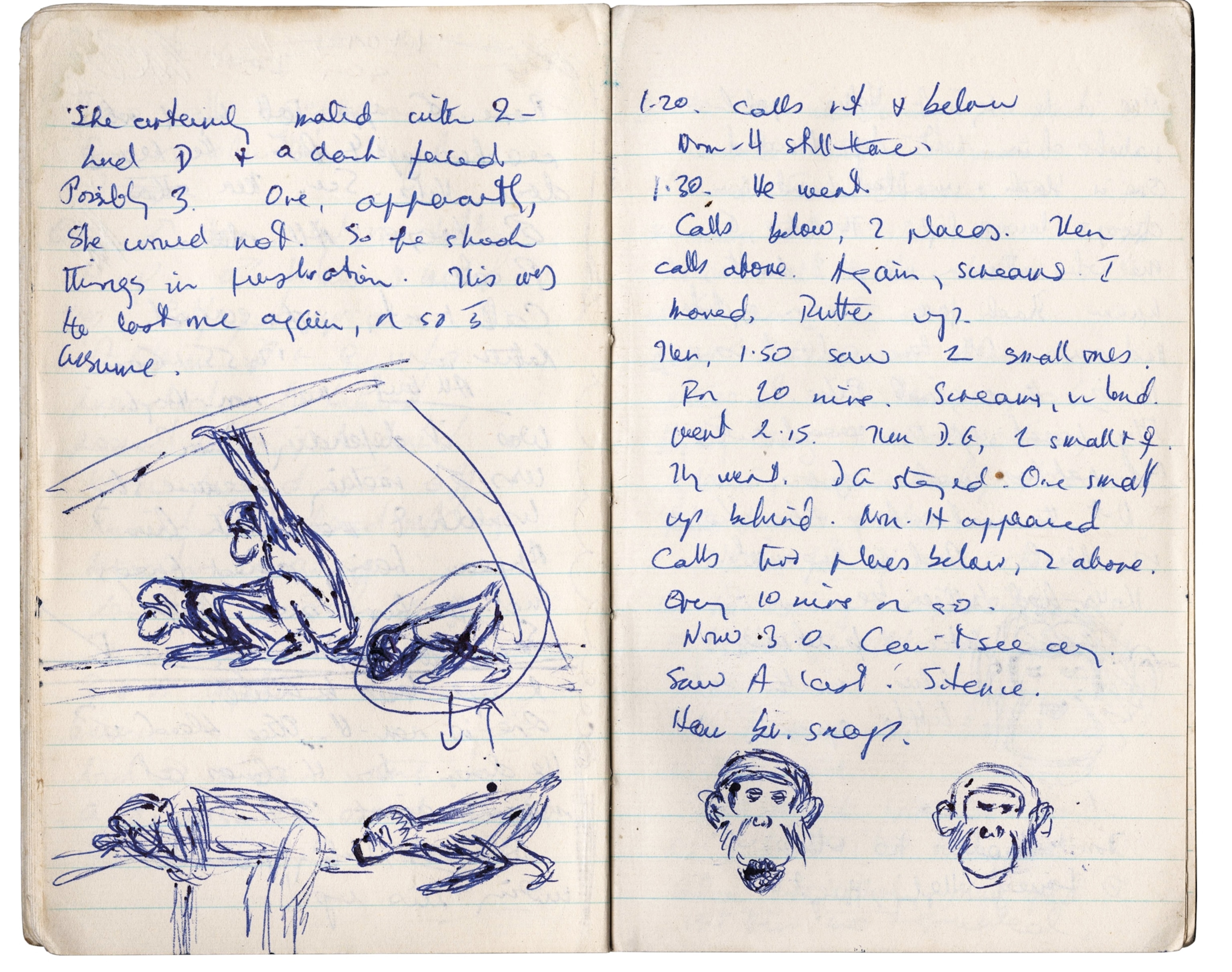

The primary aim of my field study was to discover as much as possible about the way of life of the chimpanzee before it is too late—before encroachments of civilization crowd out, forever, all nonhuman competitors. Second, there is the hope that results of this research may help man in his search toward understanding himself. Laboratory tests have revealed a surprising amount of ‘insight’ in the chimpanzee—the rudiments of reasoned thinking. Knowledge of social traditions and culture of such an animal, studied under natural conditions, could throw new light on the growth and spread of early human cultures.Jane Goodall, from “My Life Among Wild Chimpanzees,” August 1963 issue of National Geographic

“I didn’t even know what ethology was,” Goodall told me in 2010, one of many conversations we shared. “I had to wait quite a while before I realized it simply meant studying behavior.”

But when she arrived at Gombe, she was a keen and patient observer, and the chimps gradually grew to trust her. Their trust allowed her to witness behaviors previously unknown to science. Within just a few months she made three major discoveries: that chimps use tools, that chimps make tools, and that chimps can be formidable predators, hunting and killing other animals (such as monkeys) to satisfy their delectation of meat. At a time when physical anthropologists treated “man the toolmaker” as a canonical definition of Homo sapiens and the public viewed chimpanzees as benign circus-act fools, her findings resounded widely. Leakey bragged about her to scientific friends. In 1961 she got her first grant from the National Geographic Society.

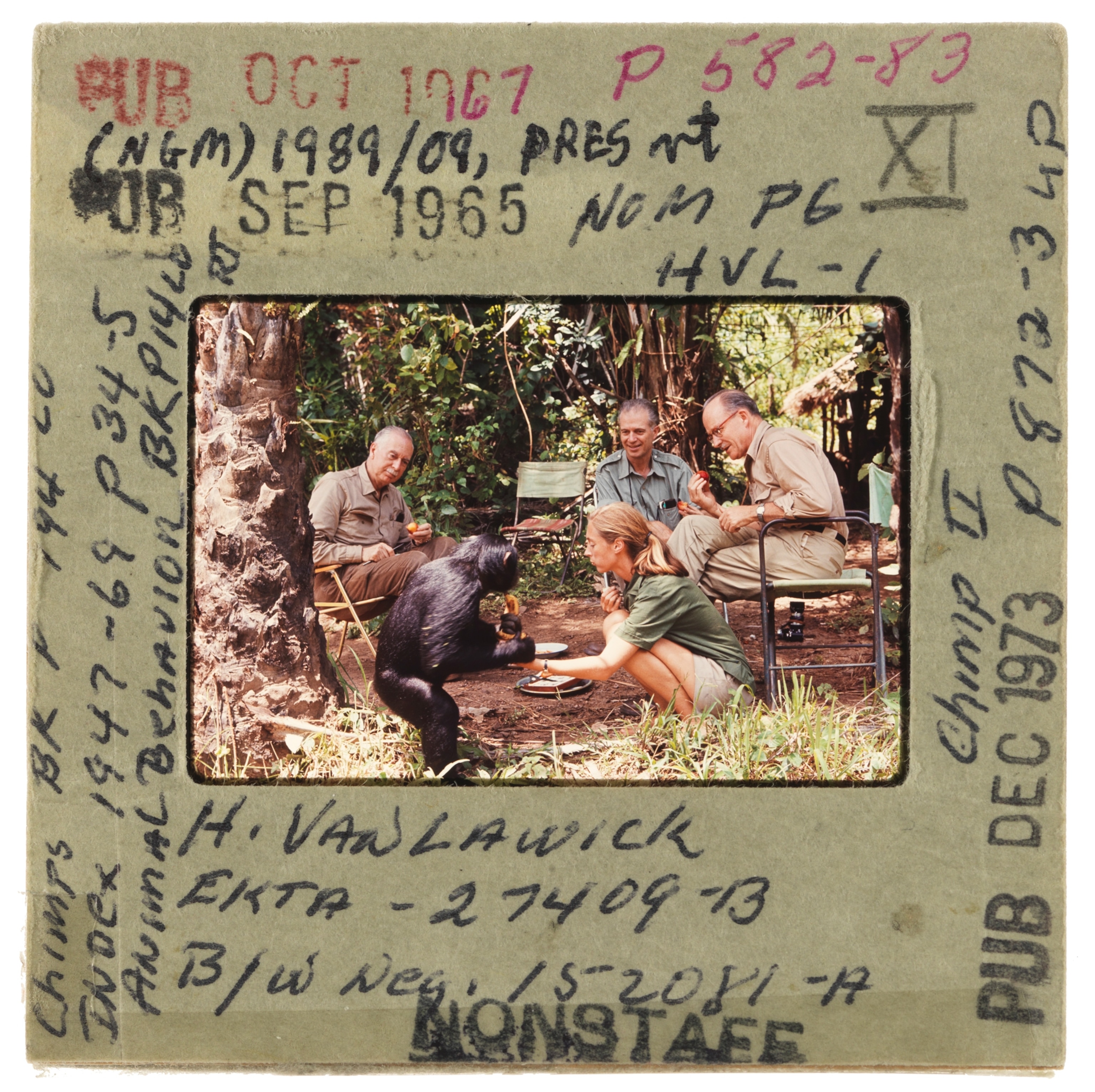

One other revelation she offered, running contrary to the dry analytics and conventional wisdom of academic ethology, was that individual chimpanzees have unique personalities. She made some of them famous to the world: David Greybeard, the first chimp at Gombe that reciprocated her tentative outreach; Frodo, the bully; Flo, the greatest and most beloved matriarch ever at Gombe, according to Goodall. She described those personages and discoveries in the pages of this magazine, beginning in 1963, and the stories made her an international icon. The accompanying photographs of the beautiful young English woman befriending apes in an African forest helped too. In 1966, never mind having skipped an undergraduate degree, she received a Ph.D. in ethology from the University of Cambridge. In 1971 the book she wrote about her time at Gombe, In the Shadow of Man, became a global hit.

(Read Jane Goodall's iconic 1963 tale of chimpanzees that still astonishes today.)

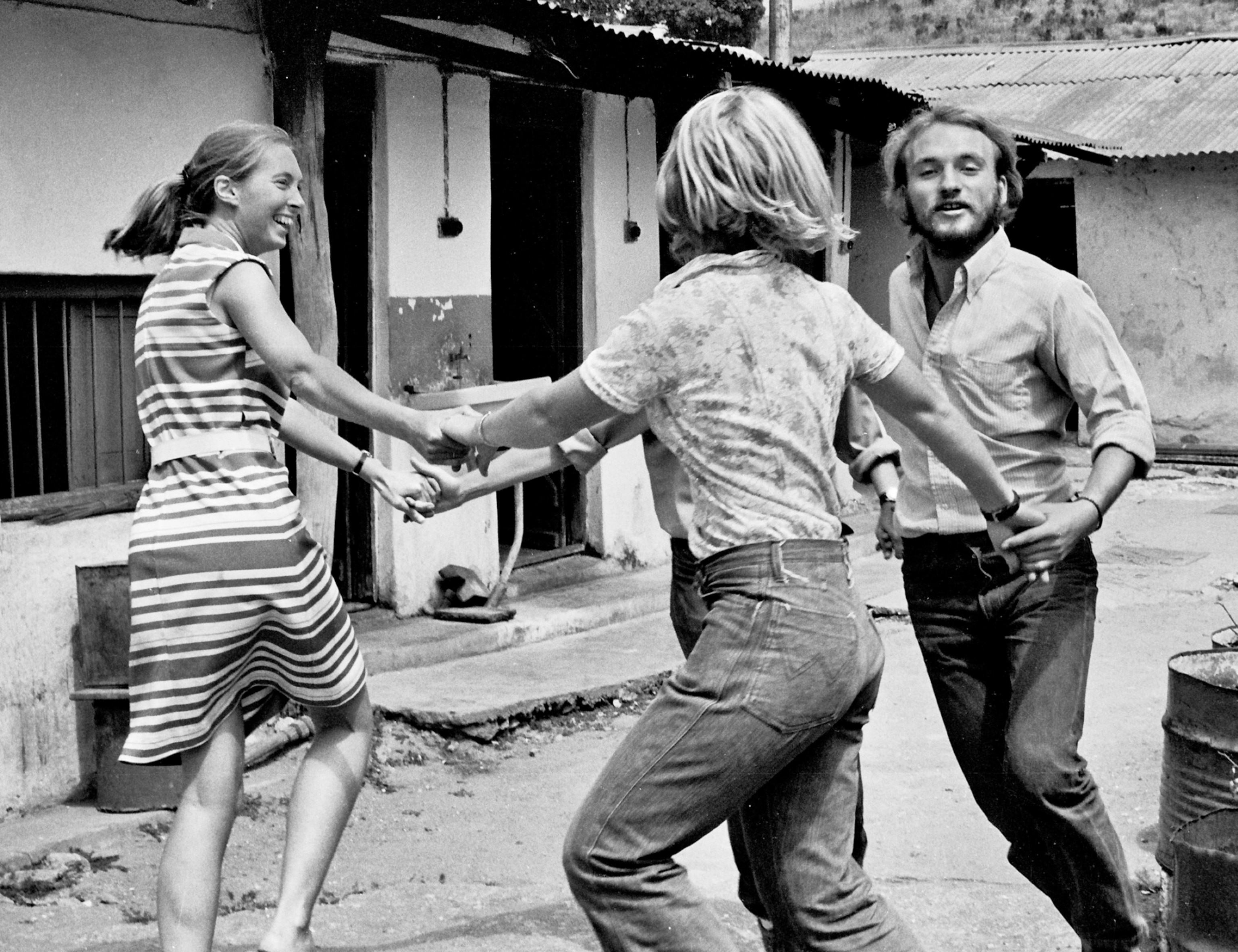

And if she was iconic, she was the best sort of icon: inspiring others to dream big, to care deeply about things that matter, to see the whole natural world through a lens of gentle fellowship. She was no secular saint, despite her aura; she was human. She could be curt, in the politest way, and judgmental. When pushed, she pushed back. She pushed back against the ethology mavens at Cambridge who informed her that animals under research should never be named or personified. She pushed back against researchers when they criticized her for “unscientific” emotionalism. She was a clarion moralist. She was a vegan. But she wasn’t priggish or stiff. Around a campfire, she could enjoy a wee dram of good single malt Scotch, maybe two drams, as much as the rest of us did.

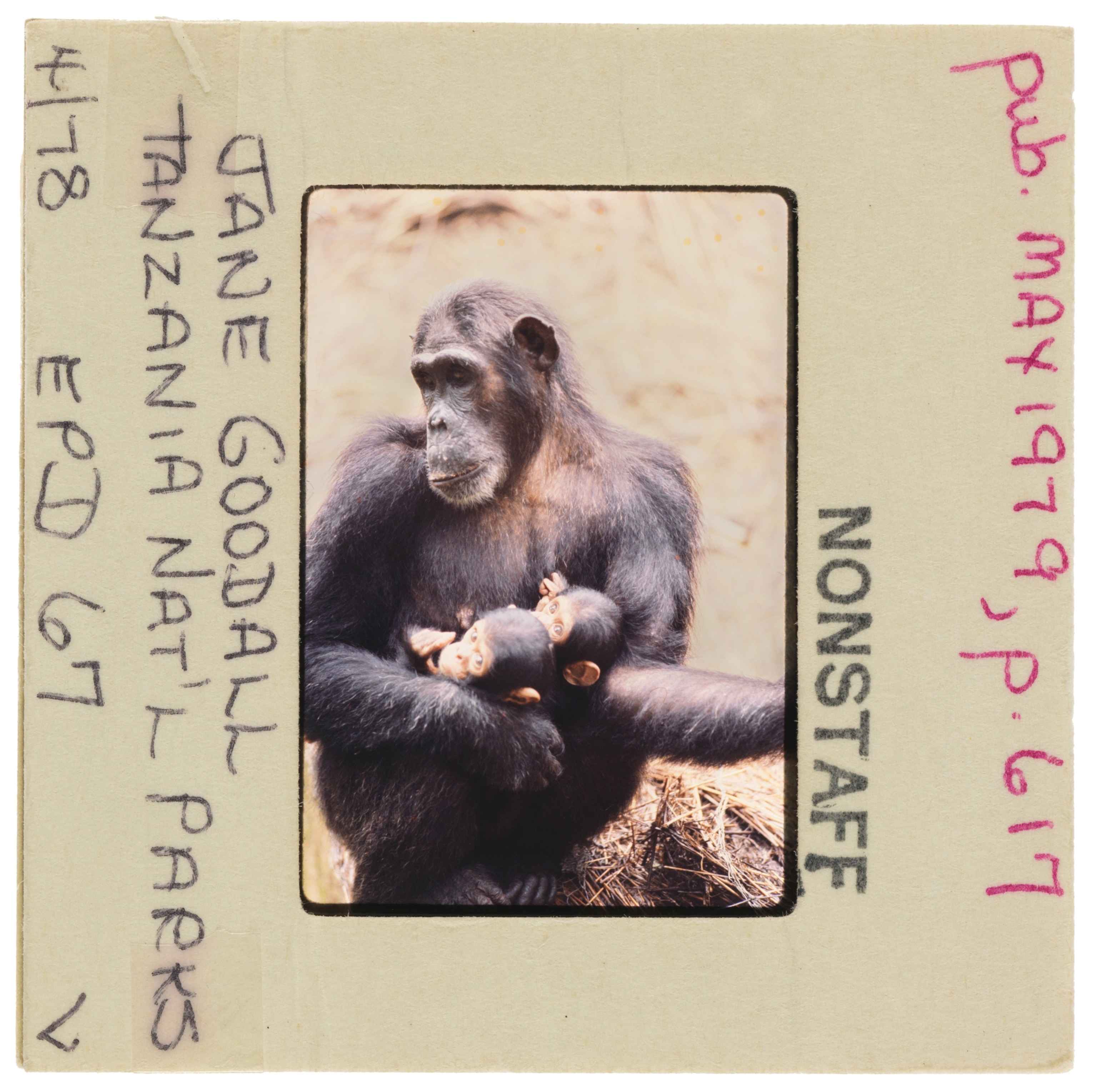

Of the more than 20 other books that she would ultimately write for adults and for children, four contain the word “hope” in their titles. The necessity of hope, against the odds, against the trends, was among her most insistent themes. She understood that hope is a duty, not a prediction or a mood. In 1977 she established the Jane Goodall Institute (JGI), devoted to the conservation of wildlife populations and the humane treatment of individual animals, such as chimps rescued from abusive captivity or orphaned by hunters. In 1991 she and JGI added a youth program for education and activism called Roots & Shoots. Over the years, she was named a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire, a United Nations Messenger of Peace, and an awardee of the Kyoto Prize. Stevie Nicks wrote a song about her. Gary Larson referenced her in a “Far Side” cartoon, with a jealous chimpanzee wife finding a long blond hair while grooming her chimpanzee husband. JGI officials were appalled by Larson’s cheek, but Goodall thought it was funny.

She was tough, the way a tussock of grass in a high wind is tough. One outing I shared with her involved an eight-mile slog through Congolese swamp forest to visit an outpost camp for the study of chimpanzees, a place so remote that the chimps there had no fear of humans. National Geographic had sent us—Goodall, conservationist Mike Fay, photographer Michael “Nick” Nichols, and me, plus a lumbering film crew—to record the interaction between Goodall and those chimps. We hiked in river sandals and river shorts, as we always did in such terrain. But Gombe is dry forest, Goodall’s experience was of a different sort, and by the time we reached the camp, after dark, her feet were blistered and raw. I’m 68, she said, are you fellows trying to kill me?

The next morning, I went to breakfast with my usual preparation—having duct-taped, protectively, over all the sore spots on my feet. (A little piece of clean paper, beneath each bit of tape, prevented sticking.) She liked the idea and asked: David Q., will you do that for me? So I duct-taped Jane Goodall’s feet.

On the second morning, before we headed into the forest, I offered a repeat treatment. No, never mind, she said, I can do it now myself. She asked me to lend her the roll of tape.

She is survived by a son, Hugo Eric Louis van Lawick; by three grandchildren; by her sister, Judy; by admirers all over the world; and not least by millions of women (including my wife) whose hopes, passions, and aspirations as young girls were fortified by her example. She is also survived by the world’s current population of 200,000 or so chimpanzees. Though their numbers continue to decline, their collective jeopardy is less severe, and their preciousness is vastly more clear, for Goodall having lived.

(See National Geographic's most iconic Jane Goodall photos.)

Perhaps the most important thing we’ve learned at Gombe is how similar we are to these creatures, with whom we share between 95 and 98 percent of our DNA. As we watch their numbers dwindle and their forests fall, their legacy becomes as clear as a Gombe stream: As they go, so, one day, may we.Jane Goodall, from “Fifi Fights Back,” April 2003 issue of National Geographic

An Explorer since 2019 and a longtime National Geographic contributor, David Quammen twice profiled Jane Goodall for the magazine, including in a 2003 story for which he trekked with her to a field camp deep within the Congolese tropical forest.