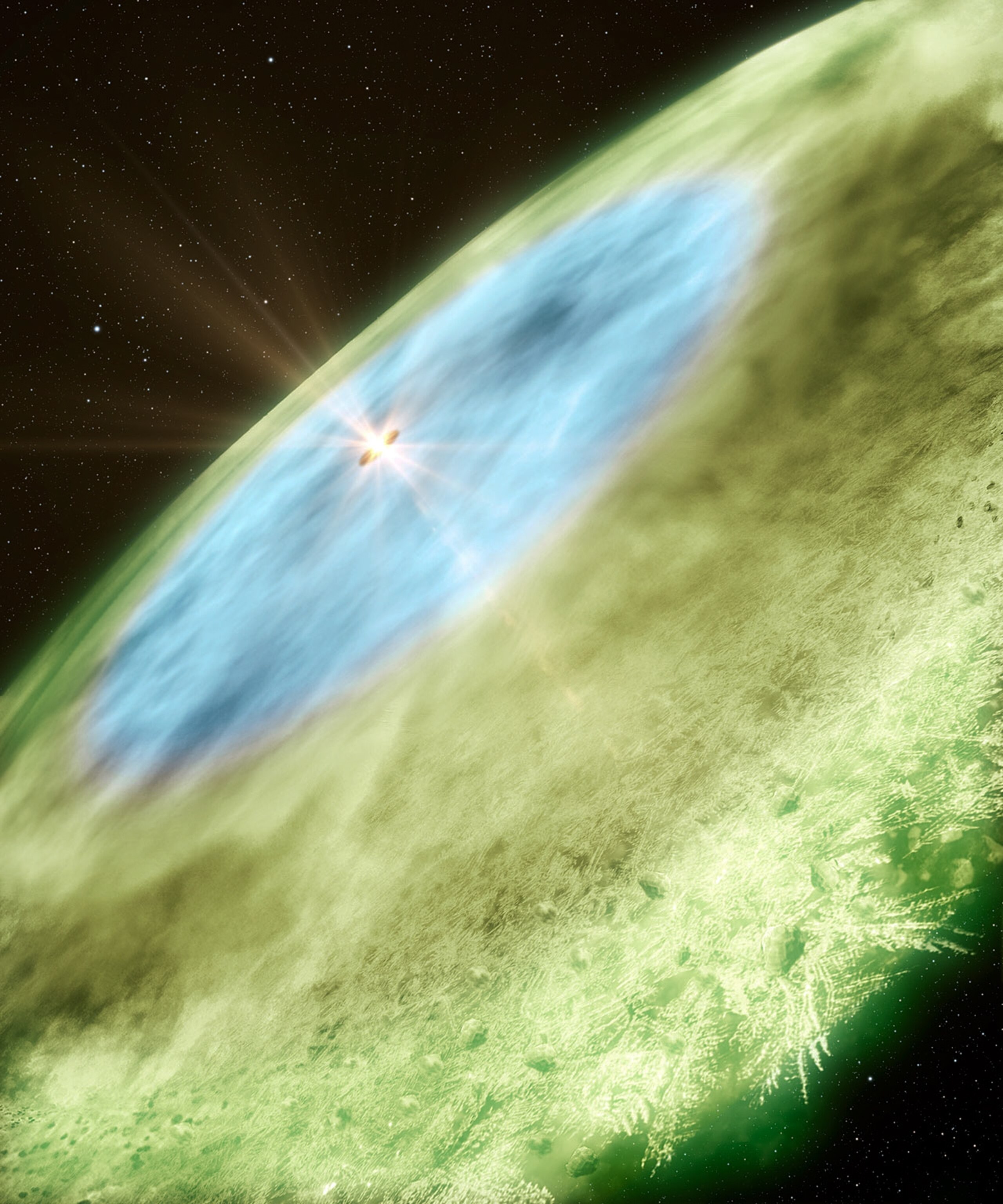

Snow Lines Around a Young Star

Snow lines in space give astronomers clues to planet formation.

A group of researchers has finally found the perfect snow line. But rather than wielding skis and snowboards, they've been using a giant array of radio antennas—called ALMA—pointed at the cosmos.

On Earth, a snow line is where snow and ice are present on the ground year-round. In space, it's where compounds like water or carbon monoxide (CO) freeze on to miniscule particles of dust in the disk of material surrounding young stars.

Celestial snow lines are important because astronomers believe they help in planet formation. (Related: "Three Theories of Planet Formation Busted, Expert Says.")

The disk of matter surrounding a young star contains the building blocks of potential planets, said study co-author Geoffrey Blake, an astrochemist at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) in Pasadena.

Over time, collisions between particles of dust the size of talcum powder grains can eventually lead to planets forming. But to speed the process along, it helps if the dust is sticky, he noted.

"Imagine you have some marbles," Blake said. "If you click two marbles together that are made of rock, they bounce off each other. [But] if you took those marbles and coated them with water or something sticky, those marbles would stick."

"That's part of the reason these snow lines are so important," he explained. The ice formed in these regions helps dust grains stick together and grow into larger bodies. (Learn more about the formation of stars and exoplanets.)

Lost in the Noise

The CO snow line reported by Blake and colleagues this week in the journal Science is located around a young star named TW Hydrae, 175 light-years from Earth. It's the first direct evidence astronomers have of such structures around infant stars.

Scientists have been trying since 2009 to get direct evidence of these snow lines. But the very structure of these disks thwarted attempts.

The disk surfaces are too hot for frozen CO. It's only when you dive down into the disk's interior that temperatures cool and CO can freeze onto dust grains. But CO gas is extremely bright, obscuring any signals from CO snow lines.

Essentially, CO snow lines are buried in a big envelope of CO gas, said lead study author Chunhua Qi, an astronomer at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Well-Behaved

So Qi, Blake, and colleagues came up with a workaround. A compound called diazenylium also shines brightly, but it's only present when CO is in its frozen form.

It emits at a different frequency than CO does, enabling researchers to pick diazenylium out of the haze surrounding the disk. And its presence means that CO is in its frozen form, indicating the presence of a CO snow line.

Qi thought at best this workaround would show a smear near the location of the snow line. "But it turns out it's clear-cut; it's a perfect ring," he said. It was very well-behaved data, Qi noted.

And he can't wait to train the ALMA radio telescope array on other disks surrounding young stars to look for their CO snow lines. He'd also like to see if there are other compounds that would indicate the presence of water snow lines or methane snow lines.

Pinning down the presence of water snow lines would be especially informative, Qi said. Researchers think that the water snow line separates terrestrial planets from gas planets, he explained.

"Finding these snow lines will give us guidelines or starting points of where these planets form and what their composition might look like."

Follow Jane J. Lee on Twitter.