5 Shipwrecks Lost to Time That Archaeologists Would Love to Get Their Hands On

The shipwrecks of some seafaring cultures have never been found—but not for lack of looking.

Finding modern ships lost at sea, even with the help of radar, sonar, and satellites, can be a herculean task. But trying to find a shipwreck from thousands of years ago is even harder. It's like looking for a wooden needle in a haystack after part of the needle has rotted away.

Underwater archaeologists keep looking, though, because finding one of these shipwrecks could yield a treasure trove of information—from how ancient peoples built their vessels to where they traveled and who their trading partners were.

Figuring out those connections would allow researchers to better understand ancient economies, and to put the cultures into a more global context, says James Delgado, director of maritime heritage for the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

The main problem with finding ancient shipwrecks is that the vessels tend to be made mostly of wood, says Cemal Pulak, a nautical archaeologist at Texas A&M University in College Station. And submerged wood doesn't fare well in the ocean because of an animal called a shipworm.

The "worm" is really a mollusk that burrows into wood, turning timber into something resembling Swiss cheese. Shipworms can break down exposed parts of a wooden wreck in as little as five years, Pulak says. In order to survive, an ancient vessel must be protected: buried in sediment or under a pile of ceramic cargo jars called amphorae, for instance.

That's how a 102-foot-long (31-meter-long) barge from the Roman Empire survived mostly intact at the bottom of the Rhône River for almost 2,000 years. Divers discovered it poking out of a mound of mud and discarded amphorae in Arles, France. (Read more about the Roman boat in this month's National Geographic magazine.)

Archaeologists are usually looking for ships in much worse shape. But advances in submersible and sonar technology are now giving them hope. The improved detection techniques could enable researchers to find ever fainter traces of ancient shipwrecks buried in the seafloor, says NOAA's Delgado.

Oceans around the world are littered with the ghostly remains of wrecks. Here are a few examples that float high on many an underwater archaeologist's wish list of potential discoveries.

Oceania

The colonization of Oceania in the South Pacific is one of the great stories of human migration. Early peoples—including the Polynesians—managed to travel thousands of miles across open ocean, says NOAA's Delgado, transporting with them delicate foodstuffs like taro, which is very susceptible to salt spray.

Finding one of their voyaging vessels would fill in the picture archaeologists have of how humans got to Australia tens of thousands of years ago, he says. "They didn't just sit on a log and paddle there," Delgado adds. (Learn more about human migration to Australia.)

Minoans

Any ship from the Minoan civilization—which was centered on Crete (map)—would be an amazing find, says Shelley Wachsmann, a nautical archaeologist at Texas A&M University. Researchers have found cargo from one of these ancient ships, which plied the Mediterranean between 4,700 and 3,500 years ago, but not the actual vessel.

Little is known about this seafaring culture. "They seem to have been the great explorers of the Bronze Age," he says, and traces of them are scattered everywhere around the Mediterranean in paintings and frescoes.

Those paintings depict long, sleek craft, much like modern-day Chinese dragon boats, says NOAA's Delgado. But without a physical shipwreck, archaeologists can only guess at how the Minoans constructed their vessels.

Wachsmann has tried looking for Minoan wrecks off the coast of Crete, but to no avail. If they're there, the shipwrecks are probably buried under too much sediment for current equipment to detect, he says.

Sea Peoples

These sailors from the 14th to 12th centuries B.C. "were coalitions of people from Italy, the surrounding islands, and Turkey," says Wachsmann. They started out much as the Vikings did, with tribes banding together to raid coastal towns in the Mediterranean. The Philistines from the Bible are considered to be part of that coalition.

Some sea peoples used a kind of ship designed by an ancient civilization called the Mycenaeans, who flourished in Greece between 1600 and 1100 B.C. "The Mycenaean ship is the forerunner of the Greek trireme," says Wachsmann. "It's an incredible ship, and we don't have a splinter of it."

Greek Trireme

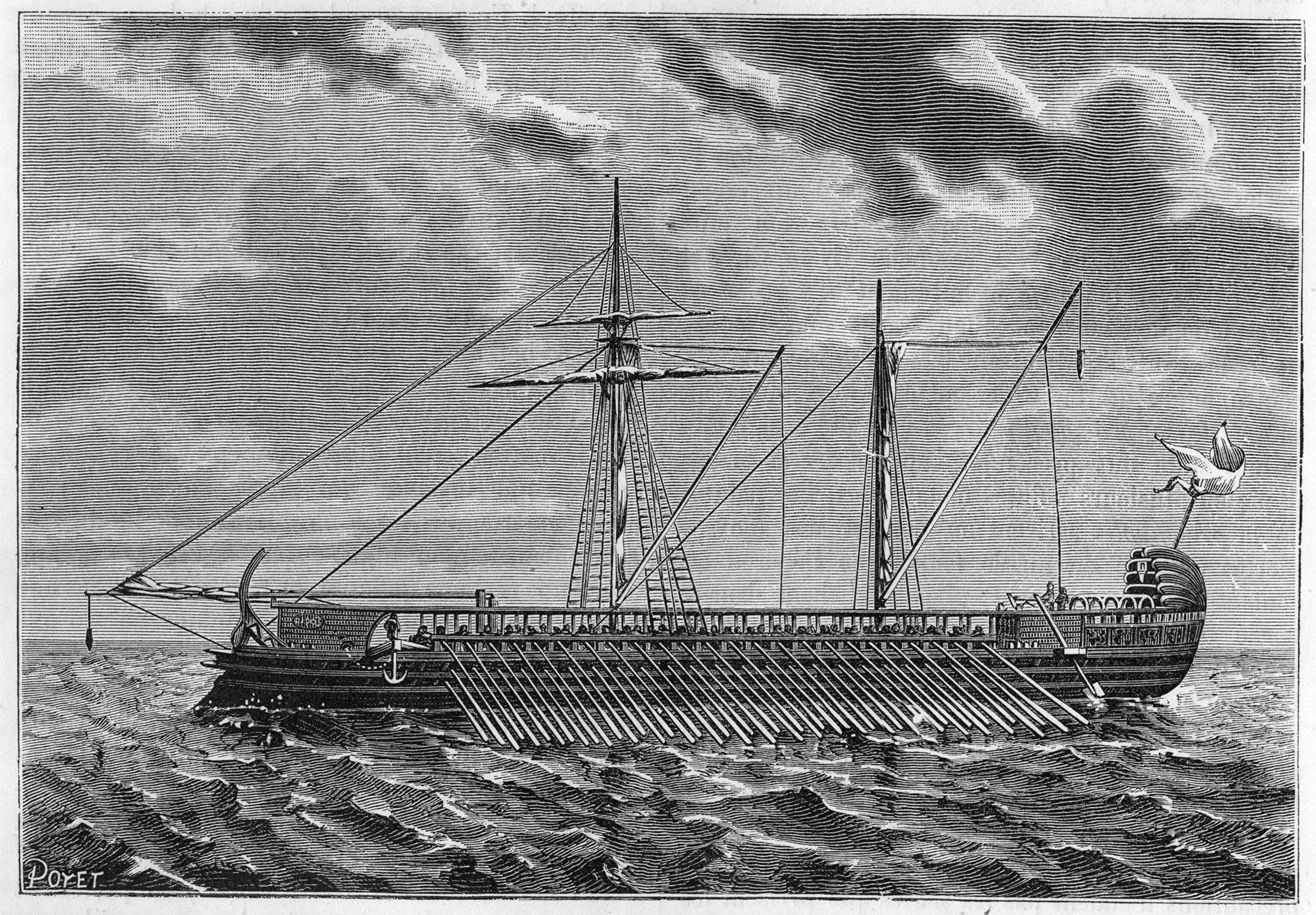

These warships are most famous for their role in the Battle of Salamis, in which the Greeks beat back invading Persian forces led by Xerxes in 480 B.C. Archaeologists have drawings, text descriptions, and examples of ancient boatyards, but they have yet to find a trireme.

"There's a lot of debate on the construction of ancient triremes," says Katy Croff Bell, an oceanographer and National Geographic explorer. Researchers even built a replica in the 1980s to try to figure out how people constructed them. (Watch videos of the replica on the ocean.)

Designed to be light and fast, the trireme was roughly 120 feet (37 meters) long and 20 feet (6 meters) wide. The vessel carried a total of 170 oarsmen, arranged in three stacked rows on each side of the boat—the origin of the vessel's name. Triremes were armed with bronze rams—some of which have been found—that were used to slam into enemy ships. (Command your own trireme in this computer game.)

"I don't think we'll ever find warships in the open ocean," says Texas A&M's Pulak. Archaeologists will probably have to look in ancient harbors that have been filled in with sand over time.

That's how a trove of 37 shipwrecks from the 5th to 11th centuries A.D.—seven of which were warships—came to light in Istanbul, Turkey. Workers building an underground railway in 2004 came across the site, located in a downtown neighborhood beside the Bosphorus. (Learn more about the Yenikapi shipwrecks.)

Shipwrecked Pharaoh

The annals of early archaeology include the tale of an Egyptian sarcophagus lost at sea. It begins with a British adventurer named Howard Vyse, who in 1837 blasted holes into the Pyramids at Giza to better explore what was inside. In the main burial chamber of the pyramid built by King Menkaure (who ruled from 2490 to 2472 B.C.), he discovered an empty basalt sarcophagus.

Vyse decided to ship the three-ton artifact to the British Museum in London, but the vessel sank somewhere in the Mediterranean in the fall of 1838. In the Loss and Casualty Book of the Lloyd's insurance company, the entry for Thursday, January 31, 1839, records that the vessel "sailed from Alexandria 20th Sept. & from Malta, 13th October for Liverpool, & has not been heard of."

In 2008 Egyptian authorities made preliminary plans to search for the vessel and its precious cargo, but the country's ongoing political troubles cut the effort short. To this day the finely carved sarcophagus awaits discovery—along with countless other relics and wrecks from antiquity still consigned to the watery deep.

Follow Jane J. Lee on Twitter.