A new expedition to Guadalcanal reveals WWII shipwrecks for the first time

National Geographic Explorer-at-Large Bob Ballard revisits the Iron Bottom Sound—rediscovering vessels, and making new finds.

Shipwreck hunter Bob Ballard recalls the solemn sense of duty he felt more than 30 years ago when he first explored Iron Bottom Sound—an expanse of water beside the island of Guadalcanal in the South Pacific's Solomon Islands that was the scene of fierce fighting in World War II.

The battles there between Allied forces—mostly American—and the Imperial Japanese Navy raged for six months from August 1942 until February 1943. The campaign marked a turning point in the Pacific War and the American victory there, some 14 months after the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, began a final phase that ended in the showdown for Japan's Home Islands.

Ballard's first journeys in the early 1990s and his most recent expedition this past July underscored the loss of life; the seven naval clashes and three major land engagements claimed more than 27,000 lives on both sides.

"This was the first battle that Japan lost badly," says Ballard, a National Geographic Explorer-at-Large. “This was when the Rising Sun began to set."

Japan capitulated to the Allies two years after Guadalcanal, on August 15, 1945, after the U.S. dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It would formally surrender the following month, on September 2, aboard U.S.S. Missouri.

Before World War II, Iron Bottom Sound was known as Savo Sound, after nearby Savo Island. But its wry nickname stuck because more than a hundred warships were sunk there during the deadly conflict. The shipwrecks that still lie on the seafloor are a grim testament to this critical moment in history—and yet, at a depth of around 2,000 feet, they remain elusive as they are much too deep for human divers to reach. Ballard’s latest expedition offered a rare chance to see these ships and restore their stories.

(80 years later, you can still see the shadow of a Hiroshima bomb victim)

In July, Ballard and his team on board the Exploration Vessel Nautilus used the latest underwater technology to survey 13 shipwrecks at Iron Bottom Sound, including some that had not been found since sinking beneath the waves—such as the Imperial Japanese Navy destroyer Teruzuki and the bow of the U.S.S. New Orleans.

Video from the underwater explorations was streamed live from the E/V Nautilus, both to a group of specialist researchers and to the wider public. Some viewers were family members of those who lost their lives on the ships, and many left comments detailing their connections to the sunken wrecks.

“My great grand-uncle, Lt. Cmdr. Edmund Billings, was on the Quincy's bridge when it was hit. His last words were (allegedly) ‘Everything will be all right, the ship will go down fighting.’ Certainly, she did." —Geoffrey Roecker, historian and creator of MissingMarines.com

The E/V Nautilus is operated by Ballard's Ocean Exploration Trust, and the expedition was primarily funded by the NOAA Ocean Exploration program. In addition to Ballard's team, researchers from the U.S., the U.S. Navy, the Solomon Islands, Australia and Japan also took part in the work.

Ballard, who once served in the U.S. Navy, says he was moved by his latest explorations in Iron Bottom Sound, as he had been in the 1990s.

"It's quite striking when you're down there, because you're where a lot of people died," he says. And this time the families of those who were killed at Guadalcanal could join in: “The beauty of our telepresence is you're with us when we make the discovery, because the moment of discovery is so thrilling,” he says.

IJN Teruzuki and the “Tokyo Express”

One of the shipwrecks that Ballard found in July was the Imperial Japanese Navy destroyer Teruzuki, sunk on the night of December 12, 1942, by American torpedoes while it was escorting a convoy carrying supplies to Guadalcanal. Teruzuki and the convoy were part of the so-called "Tokyo Express"—Japan’s months-long effort to resupply its troops on the island during the night.

American air attacks made resupply by day impossible, says Ballard. But the Allies wouldn’t develop the ability to fight at night by aircraft equipped with radar until later in the war, so the Japanese developed the tactic of resupplying their forces on Guadalcanal by night.

"We controlled the air, but they ruled the night," Ballard says. "The Japanese were extremely capable at fighting, especially at night with their Long Lance torpedoes."

This was the first time Teruzuki had been seen since it sank. Japan kept many of its naval vessels secret during the war, and so there are no known historical photographs of the ship—instead, only the images of its sunken wreck survive.

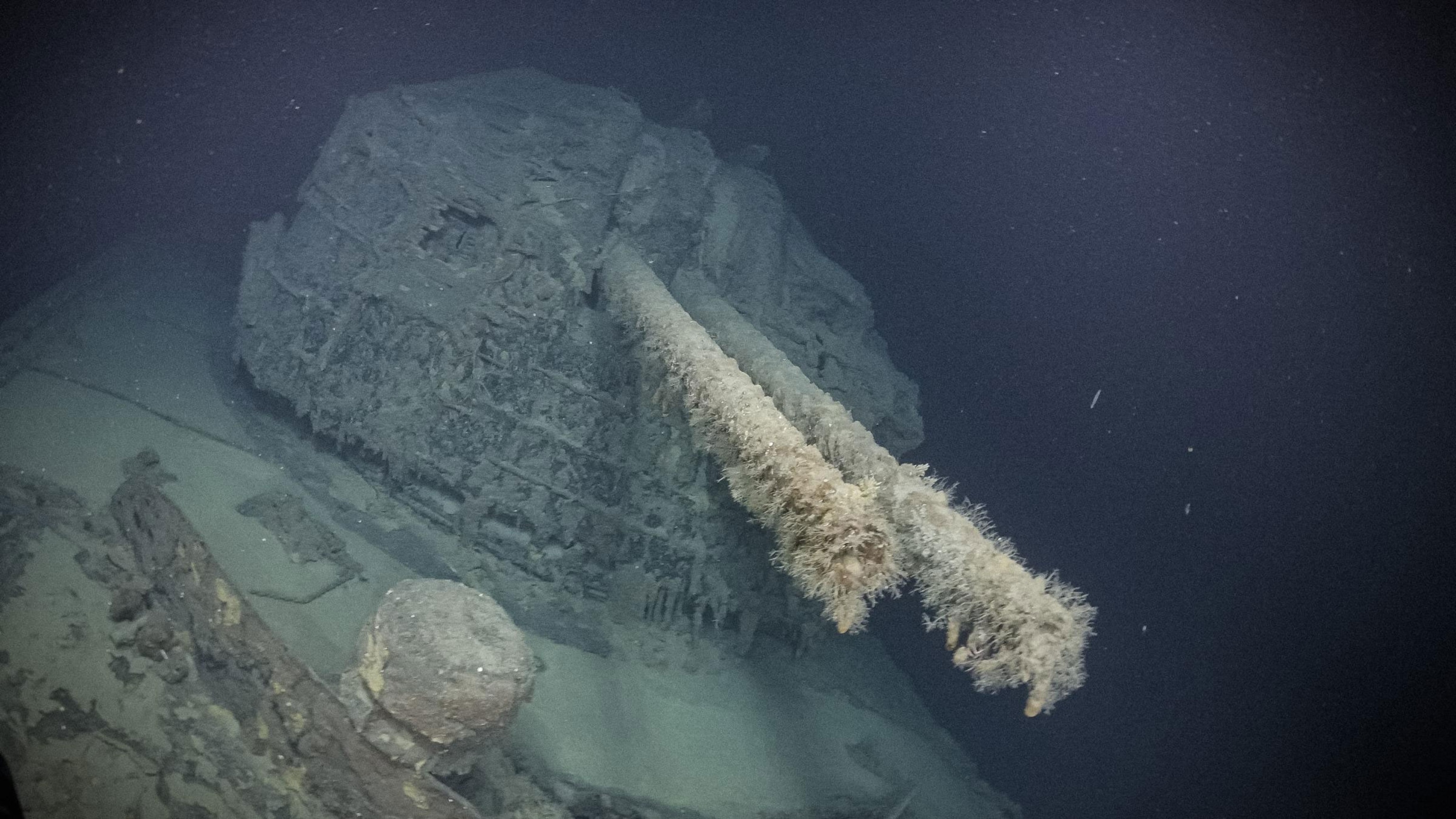

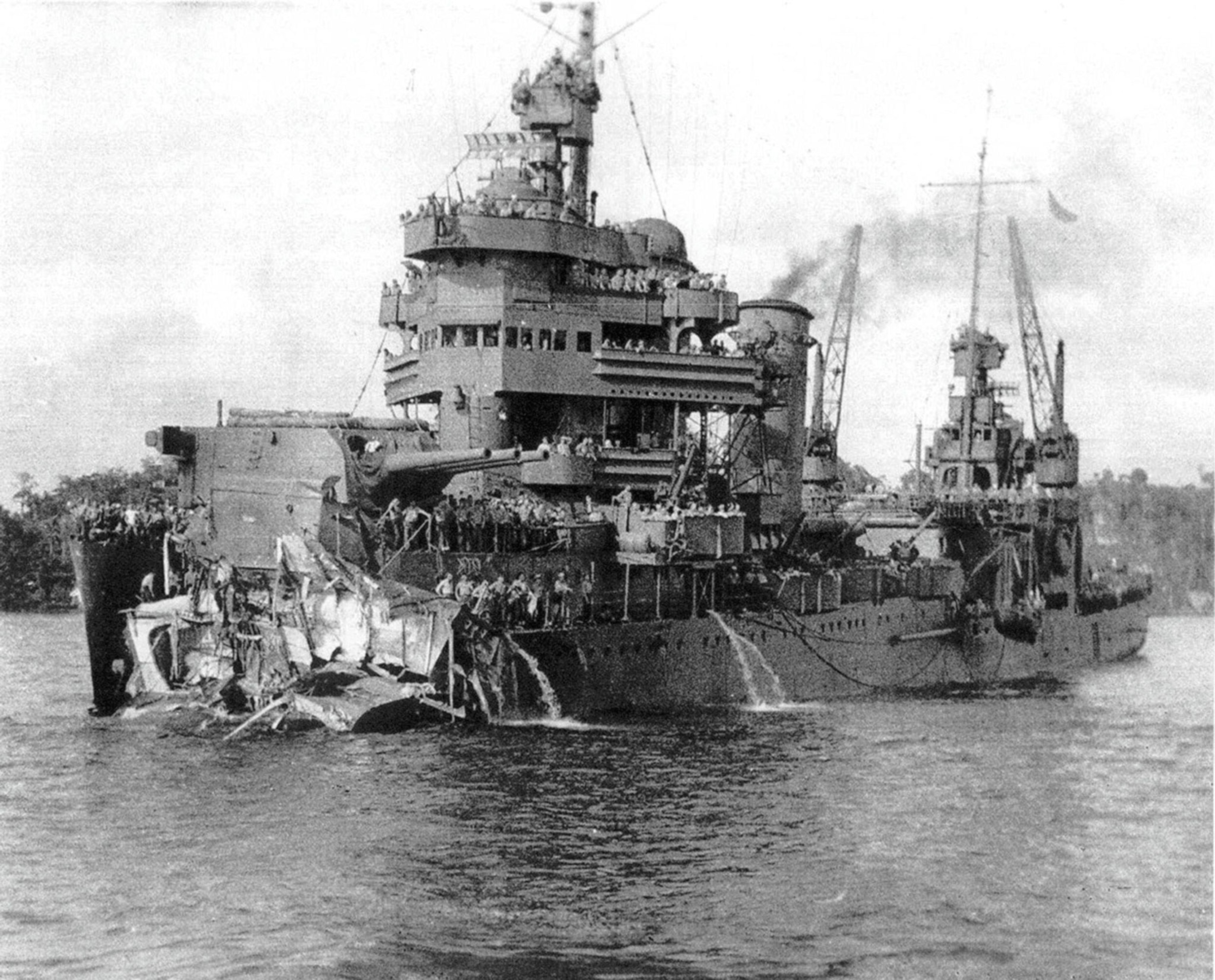

The remarkable survival of U.S.S. New Orleans

The heavy cruiser U.S.S. New Orleans was hit by a Japanese Long Lance torpedo on the night of November 30, 1942, during the Battle of Tassafaronga on the western side of Iron Bottom Sound. The torpedo struck near fuel tanks and an ammunition magazine, causing a massive explosion that tore off the ship's bow, including one of its gun turrets. But the rest of the New Orleans didn't sink. Instead, it stayed afloat thanks to the efforts of several crew members who stayed at their posts.

“RIP Theodore Hoxworth. My great-uncle was lost in the bow of the New Orleans. I have waited a whole lifetime for this to be found. I only wish My Grandma were still alive to see this." —@TBauer-s8b

Some of those brave individuals were among the more than 180 people who lost their lives in the attack. Stricken and on fire, the American warship managed to stay afloat for temporary repairs at a nearby island. It then sailed stern-first to Australia for more permanent repairs and rejoined the Pacific War in 1943.

Marine biologist Daniel Wagner, chief scientist for the nonprofit that operates E/V Nautilus, says the bow wreckage was first located in early July by an "uncrewed surface vessel" (USV) called DriX, which was developed at the University of New Hampshire. The USV was equipped with mapping sonar tuned for detecting shipwrecks far below the water's surface, which was often achieved before with autonomous underwater vehicles, or AUVs.

Once DriX had located a target, the explorers on the E/V Nautilus then investigated the site with ROVs—remotely-operated underwater vehicles—that could withstand the intense water pressure at the depth of the shipwrecks.

(Sunken shipwrecks tell the story of Alaska's 'forgotten' WWII battlefield)

Such depths are completely dark, and the expedition used two ROVs—dubbed Hercules and Atalanta—to light and to explore the wrecks, often in a "two-body" configuration with the Atalanta tethered to the E/V Nautilus on the surface and the Hercules tethered to Atalanta. This setup—known as "walking the dog"—insulated Hercules from any movements of the ship on the surface and allowed the team to precisely control the ROV's underwater location, Wagner says.

HMAS Canberra and an Allied defeat

The team used the same “walking the dog” method to explore the wreckage of the Australian heavy cruiser HMAS Canberra, which caught fire, was scuttled and sank during the Battle of Savo Island on August 9, 1942—one of the worst defeats in U.S. naval history.

The Canberra is the only non-American Allied warship known to have sunk at Guadalcanal, and it fought alongside several U.S. warships—including U.S.S. Astoria, U.S.S. Quincy, and U.S.S. Vincennes, which also sank during the battle. It was a blow for the Allies, with more than a thousand crew killed on Allied warships while fewer than 60 Japanese sailors lost their lives.

"My Dad was on the Vincennes when it went down. He never really talked about it, but he was in the water for over 3 hours." —@WilliamEvans-e1t

Ballard first found the Canberra wreck during his expedition in 1992, and he was able to explore it this time with online advice from the maritime archaeologist Mick de Ruyter, an expert on Royal Australian Navy vessels.

Military historian Craig Symonds, an expert on the Guadalcanal campaign, explains that the Allies chose to attack the island because Japan was building an airfield there that could threaten the sea-lanes between Hawaii and Australia. "The American Chief of Naval Operations decided that airfield had to be taken, which meant taking Guadalcanal," Symonds says.

But while the Battle of Savo Island was a defeat, the Allied forces had success elsewhere. U.S. Marines had taken over the airfield on Guadalcanal a few days earlier and renamed it Henderson Field. But the intense fighting for control of the entire island continued for several months, until the Allied victory in February 1943 at the conclusion of the Guadalcanal campaign.

(How one heroic crew helped win World War II’s largest naval battle)

U.S.S. DeHaven and the toll of war

Another American shipwreck at Iron Bottom Sound, the destroyer U.S.S. DeHaven, reinforces the conflict's cost in lives. The warship was one of the last sunk at in the battles for Guadalcanal, on February 1, 1943, when it was attacked by six Japanese warplanes.

The DeHaven crew shot down three of the attacking aircraft, but three enemy bombs sank the ship. On that day 167 crew members lost their lives in the attack.

The underwater wreck has shown signs of collapsing in the three decades years since Ballard last visited it in 1992. But eagle-eyed viewers of the Hercules video feed spotted the ship's bell—an iconic sight, Wagner says.

Ballard notes that each shipwreck at Iron Bottom Sound is a war grave for the people killed there—a thought that was foremost during the latest expedition. The sound is now a sacred place to many people: "When you see where the shells hit,” he says, “you can only imagine how horrible it must have been to be in those battles."