In Focus: Explosion in Planet Discoveries Intensifies Search for Life Beyond Earth

With the discovery of planets like our own just over the horizon, a new era in the search for life is about to begin.

Over the past five years, we've come to realize that in our galaxy planets are everywhere. And with scientists discovering new exoplanets by the hundreds, one more world would hardly seem to add much to the cosmic menagerie of un-Earthly delights.

Yet one planet could change everything—Earth's twin.

The search for exoplanets is narrowing to one main focus: finding a planet like Earth. In that search, astronomers have been surprised to find that the more they learn, the more they find that our own solar system is pretty strange. And until recently they hadn't found a hint of a planet like Earth anywhere they looked.

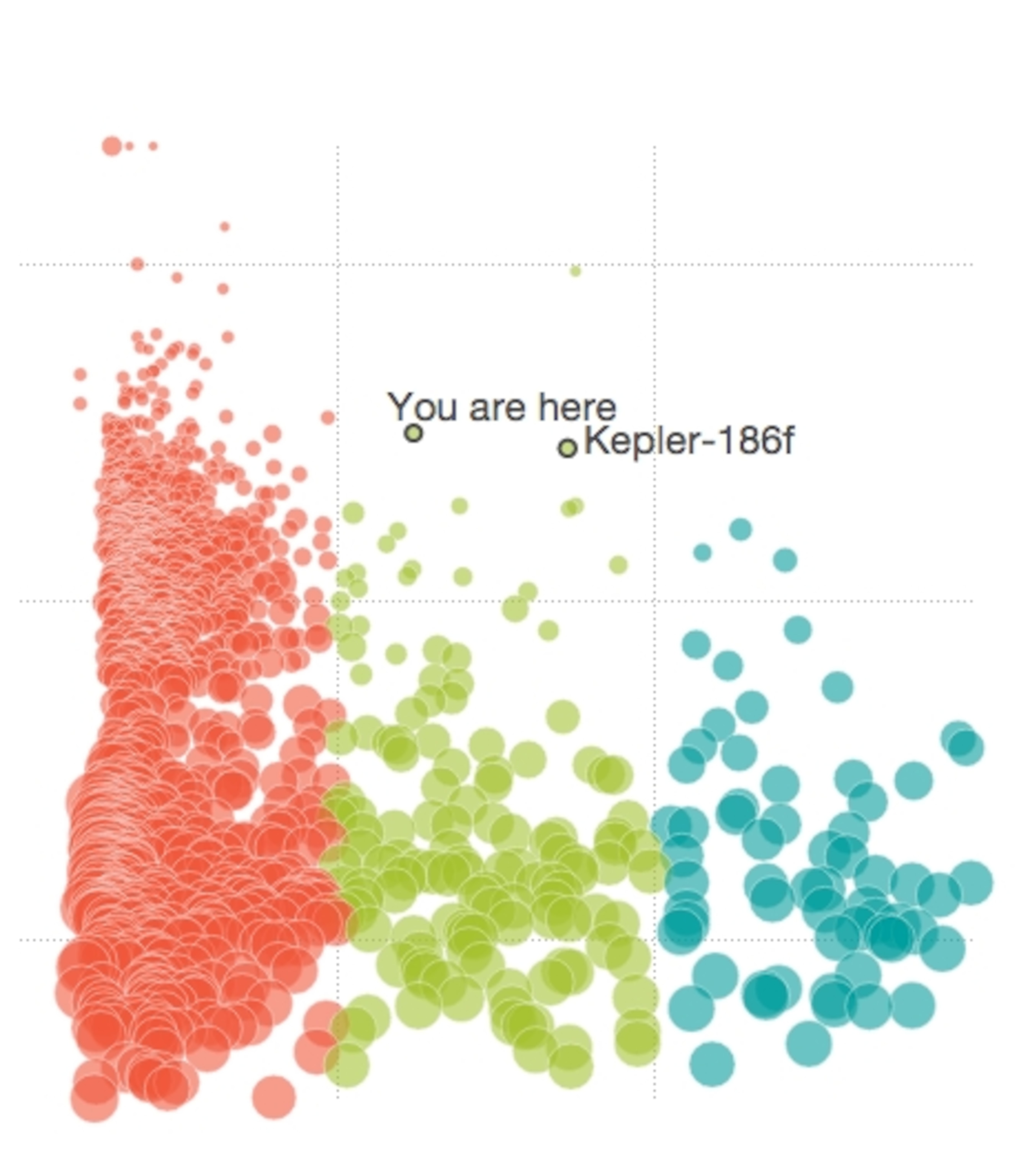

See interactive: Hundreds of Exoplanets,

a Handful Right for Life

But it's just a matter of time before a true Earth analogue appears on the cosmic horizon. Now astronomers are getting ready for the next phase of exploration—searching for extraterrestrial life by looking for the collective gasps and sighs of alien life-forms—for the gases they breathe into exoplanet atmospheres.

Ultimately, the search for planets is the search for life. And we're tiptoeing closer to finding out if it's really out there.

A Sky Full of Planets

Not too long ago many scientists questioned whether planets were even common.

"A 'serious' scientist in 1992 or 1993 had to admit the possibility that planets were really rare, that most stars might not have planets," says astronomer Debra Fischer of Yale University. "We've gone from there to here—where most stars have planets."

In the past three years alone, multiple studies have suggested the Milky Way is home to billions of worlds (though as of May 9 scientists had confirmed the existence of just 1,786). This means that on a clear night, when you go outside and gaze skyward, there's a better than good chance that most of those twinkling stars have at least one planet of their own.

Planets have been found orbiting the dead, whirling hearts of exploded stars, floating on their own through the vast cosmic ocean, and orbiting two stars at the same time. Once in the realm of science fiction, these discoveries have forced many to think about how planets could form and survive in such environments and to consider whether life could survive as well.

"Planets are the rule rather than the exception," says Erik Petigura, an astronomy graduate student at the University of California, Berkeley. He recently calculated that as many as one in five of those stars might host an Earth.

But for one watery exception, Earths have been missing from the galactic planetary census.

Our Solar System Is Weird

For nearly four years NASA's Kepler spacecraft stared from its perch in space toward a patch of sky studded with 156,000 stars. Its goal? To find the frequency of Earthlike planets in the habitable zones of stars, where temperatures are just right for liquid water to flow on a planet's surface and life as we know it might exist. The spacecraft did this by watching for the periodic blips in starlight produced when a planet passed between its star and Kepler's unblinking eye.

"Kepler changed everything for us," says Sara Seager, an astronomer at MIT. "It just blew us away."

Kepler has shown that our solar system isn't even close to a blueprint for the galaxy. Roughly 80 percent of the planets it has found have been stuffed inside the equivalent of Mercury's orbit. Closer to home? "Our inner solar system just didn't participate," says Greg Laughlin, an astrophysicist at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Some systems have giant planets orbiting so close to their stars that a year might last just several days. Others have planets that alternate in size—big, small, big, small, big—as their orbits stretch out from their sun. Some look like scaled-up versions of the Jovian or Saturnian satellite systems, in which several large, dissimilar moons make up the bulk of orbiting material.

Put more simply, the architecture of exosolar systems is as varied as the systems themselves. "The range of outcomes is much bigger than you would naively expect from looking at our solar system," Laughlin says.

Kepler and other instruments, such as the High Accuracy Radial velocity Planet Searcher, or HARPS, are also showing that the population of exoplanets is different from that of our own solar system.

In the 1990s, the first planets spotted around stars like the sun were about the size of Jupiter. These huge exoplanets were in really tight orbits and incredibly hot. That was unexpected, since Jupiter is a frigid world that isn't anywhere near the sun. Now scientists know that these "hot Jupiters" are rare and that roughly one percent of stars have them.

As a rule, small planets are much more common than large planets.

Around 2008, Laughlin says, the Swiss team behind HARPS began suggesting that many stars might harbor planets with masses between those of Earth and Neptune in small, snuggled-in orbits. For a while the claim was controversial. But, he says, "it's really been confirmed by Kepler."

So far, this is the most common class of planet found in the galaxy—a type of world that isn't even present in our solar system. These planets, which are two to four times as wide as Earth, are commonly referred to as super-Earths, or mini-Neptunes. "Fifty or sixty percent of Kepler's discoveries have been in that size range," says astronomer Natalie Batalha of NASA's Ames Research Center.

But in the solar system, there's Earth. And then there's Neptune. There's nothing in between.

How Many Earths Are Out There?

Scientists are now working on characterizing these planets. Are they rocky, like Earth, with surfaces capable of holding on to liquid (and maybe life)? Or are they small, warmer versions of Neptune with dense cores surrounded by a puff of hydrogen and helium?

A recent study suggests that in general, planets smaller than 1.5 Earth radii will probably be rocky. Above that size, planets transition from rocky denseness to something lighter. So what about all those planets, the supercommon ones, with radii two to four times Earth's?

"While very exciting, those are probably, almost certainly, not rocky planets," says Lauren Weiss, a graduate student at the University of California, Berkeley. Weiss recently used the densities of more than 60 small planets to determine that a shift may happen at 1.5 Earth radii.

"We need to be looking at planets smaller than two Earth radii—and almost certainly smaller than 1.5 Earth radii—if we want to study the rocky planets," she says.

Using those estimates, scientists can begin to fill in the numbers needed to better calculate the frequency of Earthlike planets, a figure scientists call eta-Earth. To do this, astronomers need to figure out how many rocky, Earth-size planets lie in the habitable zones of stars.

Based on Kepler data, Petigura recently placed this number at 0.22—meaning 22 percent of all sunlike stars host a rocky, roughly Earth-size planet in their habitable zone. "It's a good place to start," he says, noting that there are uncertainties in the calculation, especially concerning the habitable zone.

Calculating the Conditions Necessary for Life

The habitable zone depends in large part on the type of star and how far a planet orbits from it. But the planet itself also matters—the amount of energy a star dumps out isn't the only important factor when determining whether water could be in its liquid phase on a planet's surface.

"My version of the habitable zone has always had assumptions about the planet built into it," says Pennsylvania State University's James Kasting, who helped define the habitable zone in the early 1990s.

In determining the temperature on a planet's surface, he considers such factors as its atmosphere, whether it could have a large ocean, and how fast it spins (something scientists just measured extraordinarily precisely for a planet called beta Pictoris b). The habitable zone is a slippery concept, one that scientists are constantly revising as they learn more about planetary environments, stars, and climate models.

Officially, the closest astronomers have come to finding an exo-Earth is a small planet called Kepler-186f, announced three weeks ago. This rocky world orbits in the habitable zone of its star.

But Kepler-186f's star isn't yellow and sunlike—it's a red dwarf, smaller and dimmer. That type of star is prone to violent outbursts and other undesirables that make some scientists, including Kasting, question whether red dwarfs could nurture life.

In short, the planet is probably not a true Earth analogue. The search continues.

Finding Aliens in the Air They Breathe

The Earths are on their way, though. A handful of small candidate planets in the habitable zones of sunlike—or G-type—stars lurk in the data collected by NASA's Kepler spacecraft, Batalha says. These are the planets that, if confirmed, Kepler has been looking for all along, the ones that will help astronomers determine how common Earths are.

"This is really exciting," Batalha says. "People were speculating that we might not find the planets around G-type stars. I'm really excited that they're starting to trickle in."

The next frontier for inquiry is characterizing the atmospheres of exoplanets. It's the next step toward finding life. Some scientists, especially Seager, are keen to peer into these atmospheres and look for the signs of living, breathing, metabolizing organisms.

Some of these signals could be in the form of abnormal ratios of gases, such as oxygen and methane, that don't normally coexist unless a metabolic process replenishes them. Other clues could come from the presence of ozone, carbon dioxide, or water vapor.

Initially, such searches will be restricted to planets that have atmospheres lit from behind by the brightest of stars. No existing instrument is up to the task. But a new planet finder, the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, is scheduled to launch in 2017. TESS will survey more than 500,000 stars and is expected to identify multitudes of suitable, nearby candidates. The James Webb Space Telescope, set to launch in 2018, should be able to follow up on those findings.

Ultimately, Seager hopes to launch space probes dedicated to the study and detection of exoatmospheres. One proposed probe, called Exo-S for now, would directly image and characterize planets with the help of a far-flung, light-blocking "starshade." This probe and another mission, called Exo-C, are currently under review by NASA.

Eventually, Seager says, astronomers will be able to assemble information about the atmospheres of many exoplanets. If something really weird pops up among all that data, it might be a sign of alien life.

This kind of strategy will help deal with a troubling point raised last week. Scientists reporting in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences discussed the possibility of exomoons contaminating atmospheric measurements. From this far away, it wouldn't be possible to distinguish a moon with its own atmosphere from its planet. But that would still be a fascinating find, notes Seager.

For now, Earth is still alone. But maybe not for long. Every day, scientists move closer to finding Earth's twin and understanding our crazy solar system's place in the starlit cosmic sea.

Follow Nadia Drake on Twitter.