Earth always has more moons than you think

Astronomers recently detected a stray quasi-moon in our planet’s orbit, but it's hardly the first stowaway to hang out around Earth.

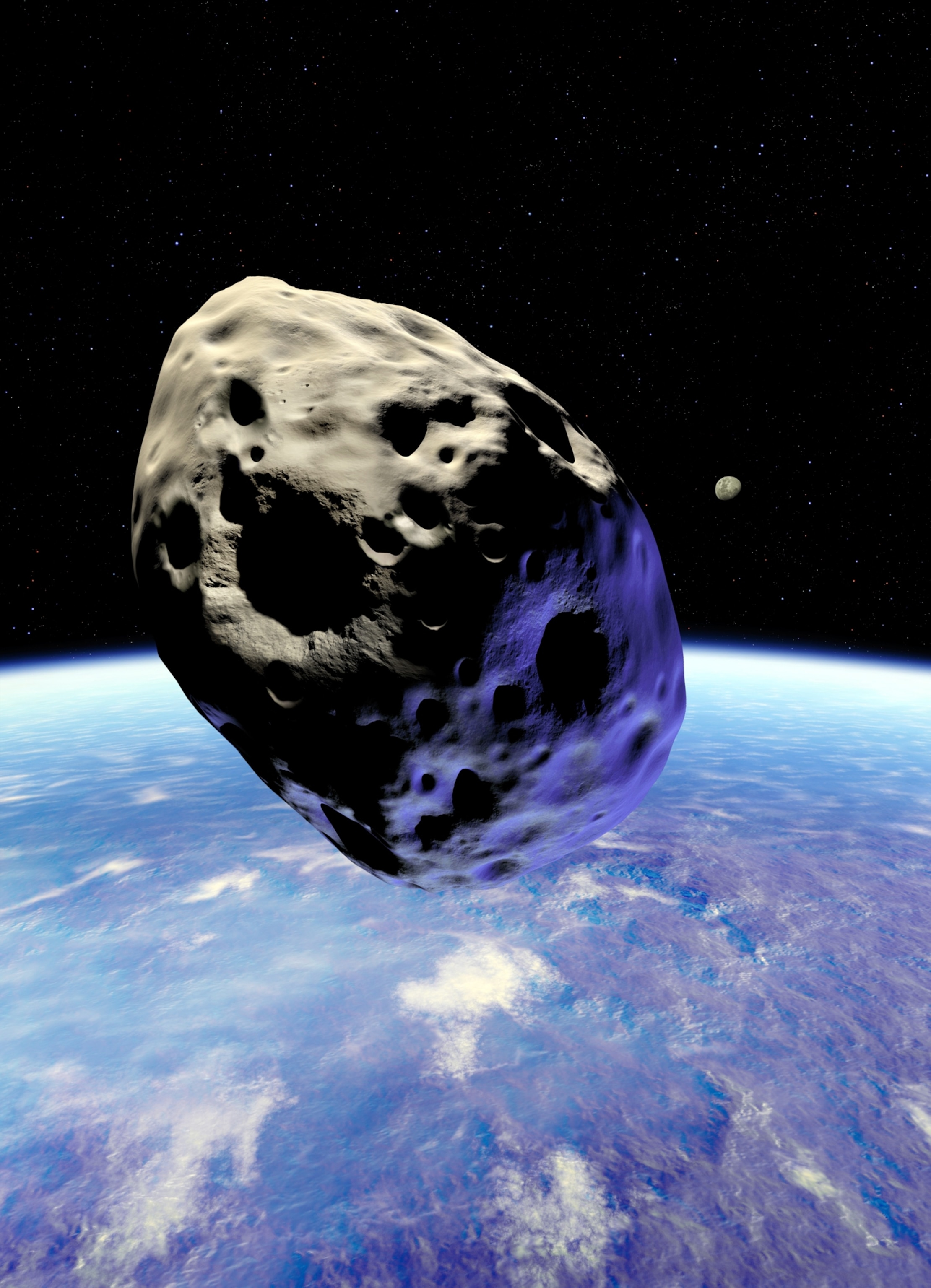

The solar system has some exciting local news: A mysterious space rock, about the size of a building, is coasting alongside Earth on its journey around the sun. Unbeknownst to astronomers until this summer, the object has been shadowing the planet for decades, in a celestial configuration that makes it a "quasi-moon."

When Ben Sharkey, an astronomer at the University of Maryland, first heard about PN7, as scientists now call it, their first thought was: "Oh cool, another one." That's because PN7 is just the latest find in what is a perpetual parade of tiny, moon-ish objects in Earth's vicinity.

Our planet has other quasi-moons like PN7; these orbit the sun, but their looping path through space—sometimes gliding ahead of Earth, other times drifting behind it—make them appear as if they are really circling the planet. And there are mini-moons, which are actually captured by Earth's gravity and temporarily orbit the planet before breaking free.

None compare to the moon, Earth's only natural satellite, the numinous crown jewel of the night sky. These other objects are only visible to powerful telescopes, particularly the kind designed to catch the faint sunlight glinting off miniscule, fast-moving rocks in the darkness. But each new discovery is a reminder of a delightful reality about our cosmic neighborhood: Earth always has more moons than we think.

"They really make you reconsider a nice, orderly, static view of the solar system," Sharkey says.

What are quasi-moons?

In the solar system, Earth isn’t the only planet with stowaway satellites; astronomers detected the very first known quasi-moon around Venus in 2002. The discovery of PN7 brings our planet's count of known quasi-moons to at least seven. (There are likely more, moving undetected.)

These small bodies can slide in and out of a shared orbit with Earth by gravitational happenstance, Sharkey says, and they experience tiny gravitational tugs from our planet. The quasi-moons discovered so far have ranged in size from 30 feet to 1,000 feet; PN7 is currently suspected to be one of the smallest of the bunch.

PN7, which was detected by the Pan-STARRS Observatory in Hawaii in late August, synced up with Earth sometime in the mid-1960s, before the first humans set foot on the moon. Scientists predict that PN7 will wander into a different kind of orbit around the sun in 2083. The duration of such arrangements varies; another object discovered by PAN-STARRS in 2016, Kamoʻoalewa, has held quasi-moon status for about a century, and will maintain it for the next 300 years.

Mini-moons come about by gravitational chance too, except Earth truly snaps them up. These purloined rocks usually circle the planet for less than a year; their orbits are quite unstable, and they can easily fly off. Astronomers have only observed four mini-moons so far, the latest one, about the size of a school bus, ditched Earth last year after a few months.

(Read more about Earth’s latest mini-moon.)

Most mini-moons are "quite small, like boulders," which means that they are difficult to detect, says Grigori Fedorets, an astronomer at the University of Turku in Finland. There are no known mini-moons currently lassoed around Earth, but an analysis by Fedorets predicts that Earth has a mini-moon measuring several feet across at any given time, and another analysis suggests that the planet could have six of similar size.

What is a moon anyway?

It might seem like a stretch to refer to a boulder as a moon, even a miniature one. The same can be true of some smaller quasi-moons like Kamo’oalewa, which is about the size of a Ferris wheel. Indeed, astronomers don't have an official set of rules for labeling and categorizing objects that can masquerade as moons.

In 2018, a team of scientists reported that they had found two "ghost moons," hazy clouds of space dust orbiting alongside the moon. If each cloud contains many grains of material, Sharkey says, "would you call that one ghost moon, or do you call it 100,000 moons?"

Still, maybe-moons bring a certain immediacy to astronomy that some far-flung wonders can't achieve. Kat Volk, a planetary scientist at the Planetary Science Institute in Arizona is sometimes jealous of her colleagues who study this stretch of the solar system, and thus can witness the entire journeys of the moonish objects they study. Her own targets of interest, small celestial bodies beyond Neptune, "won't even go around the sun once during my lifetime because their orbital periods are so long," Volk says. But the journeys of quasi-moons and mini-moons in the inner solar system unfold on significantly shorter timescales, providing "a really fun real-world example of orbital dynamics," she says.

Where do these extra moons come from?

Scientists are still trying to pin down the origins of Earth’s occasional visitors, Sharkey says. They could be near-Earth asteroids, a community of thousands of space rocks that once belonged to the solar system’s main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. At some point, Jupiter, the gravity king, may have jostled them into the inner solar system.

Alternatively, maybe-moons might be pieces of our moon that were scooped out from the lunar surface by collisions from other rocks careening through space. When Sharkey and their colleagues studied the quasi-moon Kamoʻoalewa, they found that its composition appeared "more lunar-like than any other asteroid we've looked at before," more weathered and sun-scorched than typical near-Earth asteroids. (The most recent mini-moon bore signs of lunar ancestry, too.)

A serious exploration effort of Kamoʻoalewa is already underway and could help determine its origins. This spring, China dispatched a mission that will reach Kamoʻoalewa next summer; the probe will sweep some rocky fragments from the quasi-moon and return them to Earth for scientists to analyze.

Still another theory posits that these objects are the last survivors of an ancient population of asteroids that coalesced near Earth during the early turbulent days of the solar system. But, Sharkey suggests, why pick just one explanation? Earth's extra moons—past, present and future—could be all three.

More maybe-moons are coming

Astronomers say that telescope technology has only recently become good enough to spot small bodies like PN7, and they're eager to see what kind of moon-esque objects are uncovered next by powerful instruments, particularly the new Vera C. Rubin Observatory.

(Earth's newest telescope could solve astronomy’s biggest mysteries.)

When scientists observe these objects, Fedorets says, they're engaging in a very old subject—the study of celestial mechanics—that once completely reoriented humankind's place in the heavens, booting Earth from the center of the known universe. Of course, a bunch of mini-moons will not trigger a Copernican-level shift in scientific understanding. But they are a reminder that the cosmos is always in motion, with gravity quietly and constantly rearranging the celestial landscape even this close to home—and that humans have only relatively recently figured out how to catch those changes in the act.

One thing is unlikely to change: Earth cannot permanently capture another true moon, one that won't catapult away at the tiniest gravitational disturbance, says Fedorets. That would require a close encounter with a massive, planet-sized object, he says, and "in this history of the solar system, it's not possible anymore."

But the future is likely brimming with travel buddies like PN7. Each one is a little salve against the cosmic loneliness of Earth, the only planet in the solar system with just one satellite.