Birth Mystery of Stellar Snow Globe Deepens

Astronomers thought they'd figured out where giant clusters of old stars come from. Hubble images have sent them back to the drawing board.

The Hubble Space Telescope's recent images of giant balls of stars in a nearby galaxy, reported on Thursday, have astronomers puzzled as to the star balls' origins.

Multitudes of such "globular" star clusters, each filled with hundreds of thousands of the oldest stars in the universe, lie scattered around our own Milky Way and other galaxies. But how and why they're born has long been a mystery. (See "Stars: Billions and Billions.")

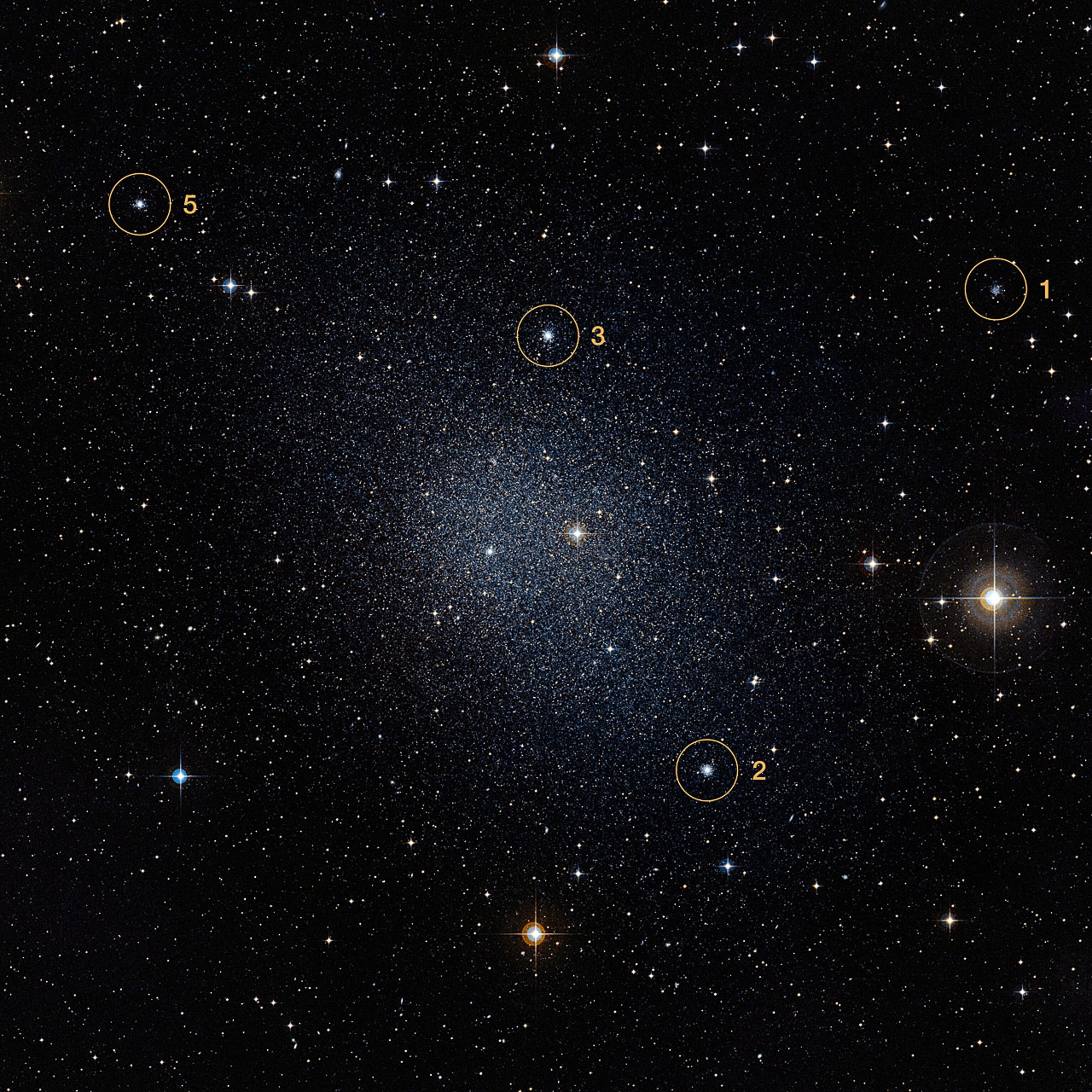

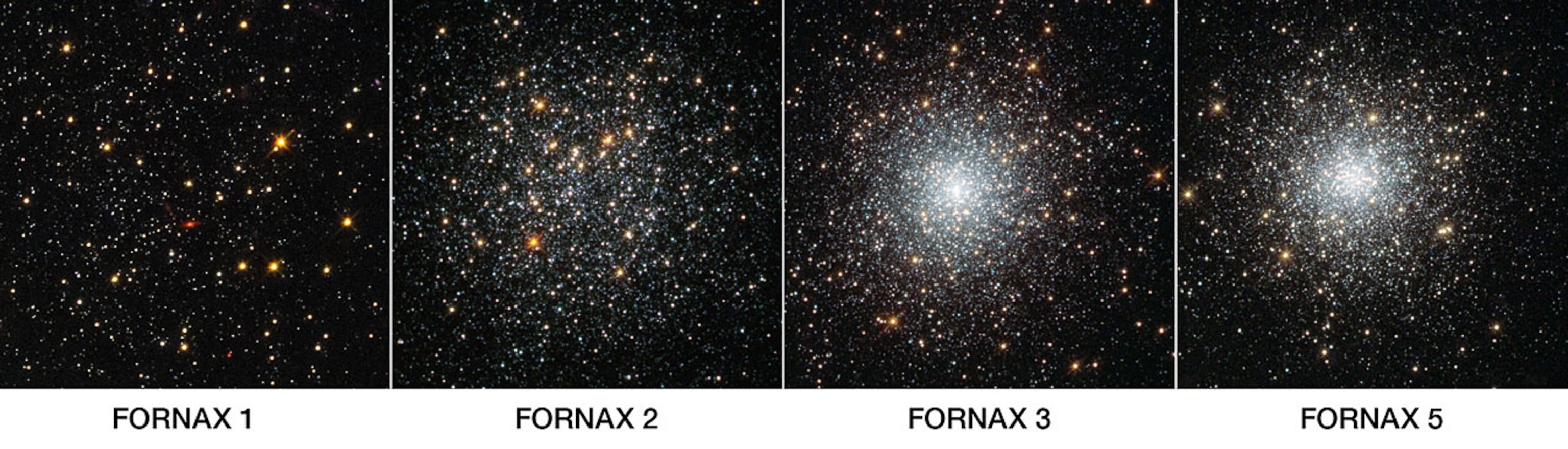

Based on observations of our home galaxy, astronomers thought that globulars must form in galactic regions that are awash in elderly stars. But Hubble's observations of the Fornax dwarf galaxy, a small satellite of the Milky Way some 460,000 light-years from Earth, have upended that idea. A paper in the Astrophysical Journal on the Fornax galaxy shows that it's home to four globular clusters—yet there aren't many old stars in its host galaxy.

"Our leading formation theory just can't be right," said astronomer Frank Grundahl of Aarhus University in Denmark, a coauthor of the new paper, in a press statement.

Generation Gap

Globulars in the Milky Way are thought to contain two generations of stars, most of them younger ones. Many of the older stars, astronomers theorized, had at some point been ejected from the galaxy and had then gathered into populations of old-timers.

If that theory's correct, then we should see a lot of old stars hanging around the globular clusters in the Fornax galaxy. But that's not the case.

"If these kicked-out stars were there, we would see them—but we don't!" said Grundahl. "There's nowhere that Fornax could have hidden these ejected stars, so it appears that the clusters couldn't have been so much larger in the past."

So now astronomers will have to go back to the drawing board and come up with a new theory to explain how these beautiful stellar snow globes came to be.

See for Yourself

That's too bad for astrophysicists, but stargazers can still enjoy globular clusters. The Fornax dwarf galaxy and its globulars are visible only through large telescopes or in long-exposure images. But there's one beautiful globular cluster right here in our own Milky Way. Called Messier 15, it's gracing the night sky right now. And backyard watchers can see it with nothing more than binoculars or a small scope.

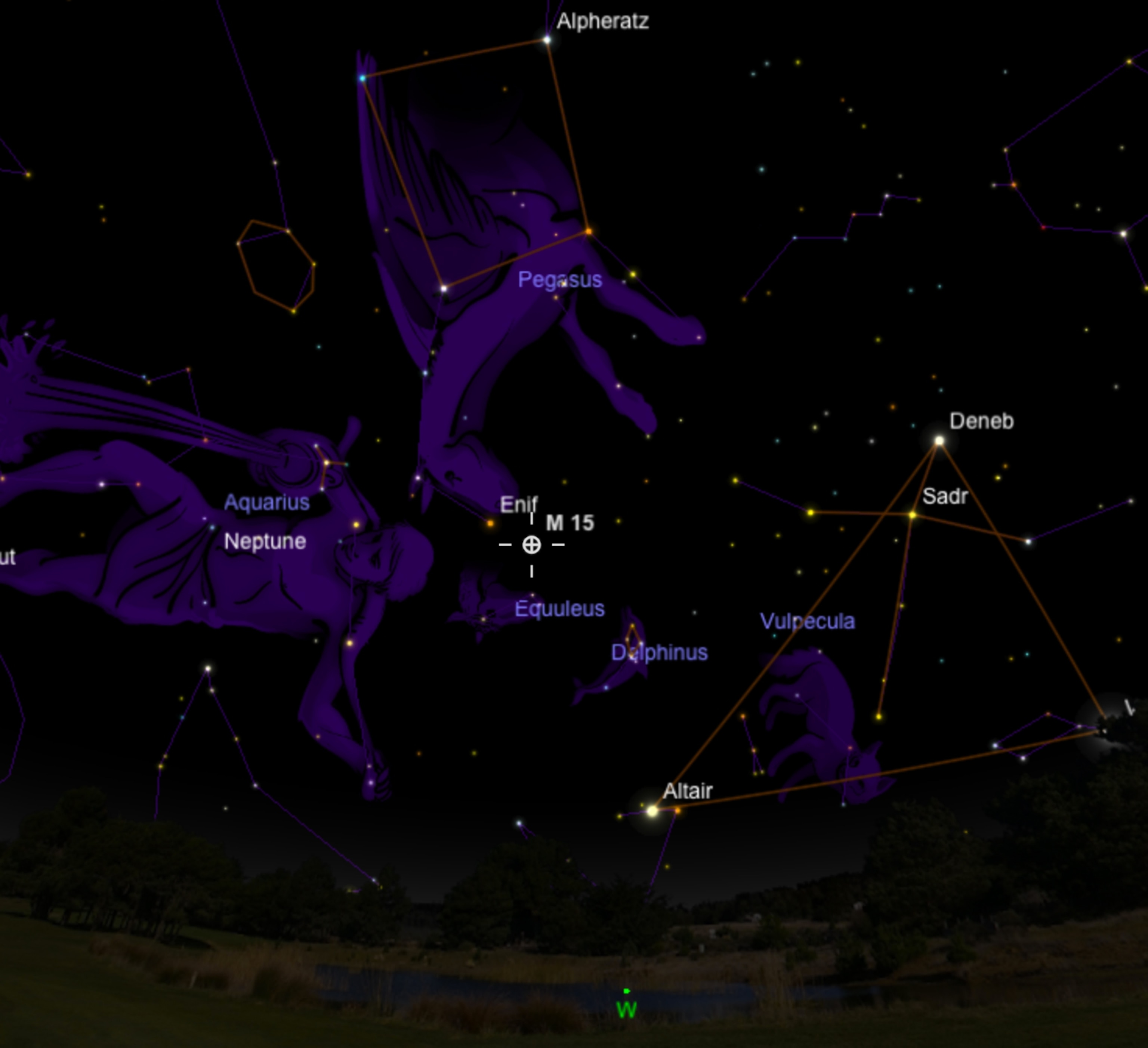

Sitting just off the tip of the nose of the constellation Pegasus, Messier 15 (M15) is one of the most beautiful globular clusters in the entire sky and quite easy to find.

Start your hunt with the Great Square of Pegasus, sitting halfway up the western sky. Then star hop across the mythical horse's neck to the third faint orange star, Enif. Messier 15 lies about 4 degrees—equivalent to eight full moons side by side—to the lower right of the star. Both are visible in the same binocular field of view.

Shining at magnitude 6.2, M15 looks like a fuzzy blob through binoculars, but it's a dazzling, bright cluster through even a small telescope. This stellar snow globe lies about 34,000 light-years from Earth, measures 170 light-years across, and is home to an estimated 400,000 stars.

Recent x-ray observations made by the orbiting Chandra Observatory of M15's highly compact core show that it spews out a lot of intense radiation. That means there may be a black hole at its heart, hidden underneath all that beauty.

Clear skies!

Follow Andrew Fazekas, the Night Sky Guy, on Twitter, Facebook, and his website.