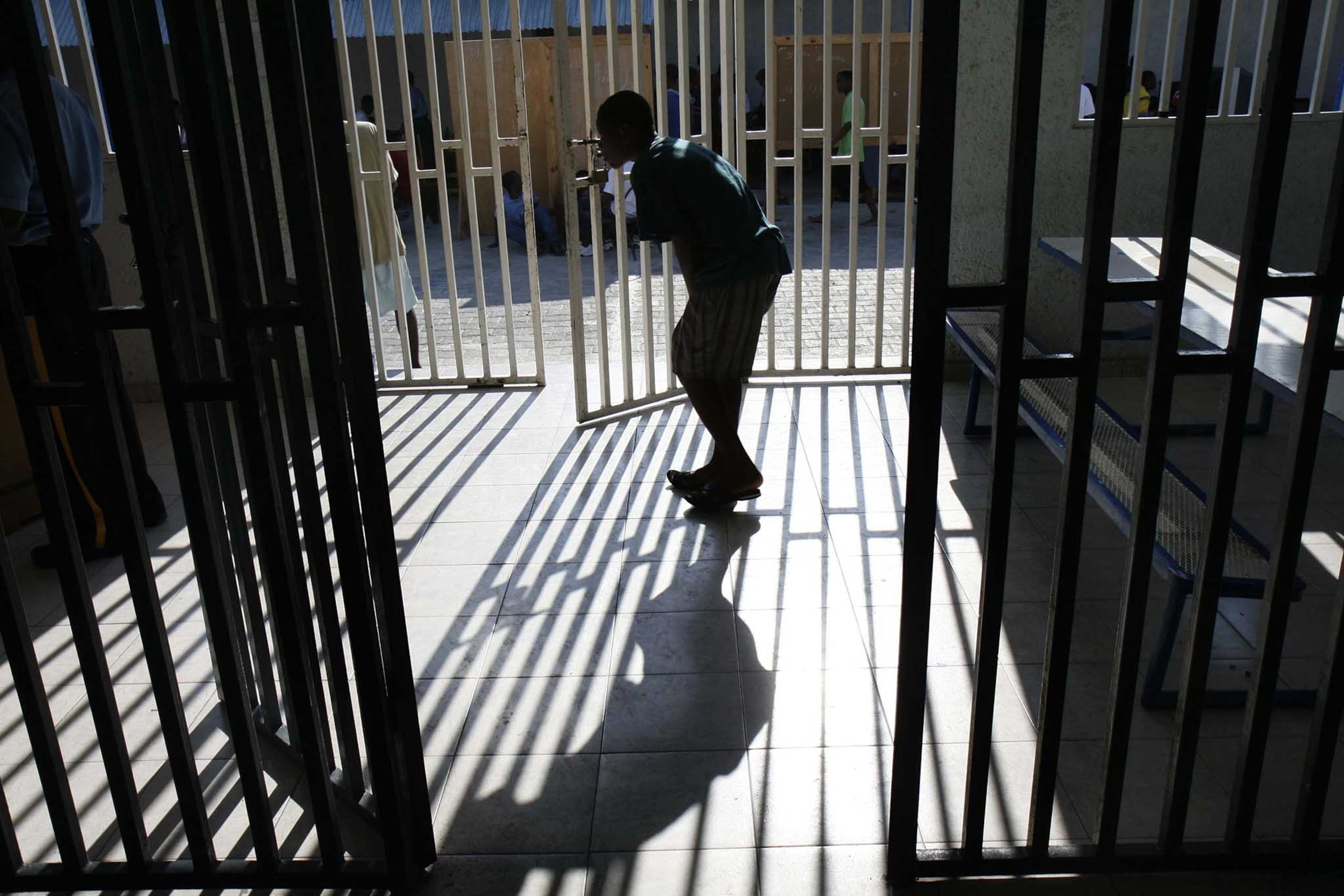

The assignment was to document the lives of crack addicts in Miami. But photographer Michel du Cille left his camera behind—intentionally. He wanted to spend his first weeks in the housing project getting know his subjects as people. The camera could come later.The resulting photo essay for the Miami Herald won the 1988 Pulitzer Prize for feature photography. He had shared a spot news Pulitzer two years earlier for his coverage of an erupting volcano in Colombia in that same newspaper.Du Cille, who won a total of three Pulitzers as a photographer for the Herald and, later, the Washington Post, died Thursday of a heart attack while covering the Ebola crisis in Liberia. He was 58.

For more than 40 years, he worked tirelessly to offer "dignity to subjects I photograph, especially those who are sick or in distress while in front of my camera," he wrote in an October essay in the Post about working in the Ebola zone. That professional mantra was guided by his caring nature, says National Geographic's Digital General Manager Keith Jenkins, whom du Cille hired as a Post photographer in 1992.

"Michel had a tremendous amount of of empathy for his subjects. It was something he valued over anything else," says Jenkins, who considered du Cille a mentor and friend. "And he photographed his subjects in a way that allowed people looking at the photographs to also have empathy for and a connection with the people in the photographs."Jenkins worked with du Cille on the Washington Post investigation of the mistreatment of war veterans at Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington, D.C. As with his Miami addiction essay, du Cille took the time to learn about the veterans he photographed, meet their families, and hear their stories. That story won him a third Pulitzer Prize in 2008.

"He spent a lot of time building relationships that were powerful and emotional before taking the photos," says Jenkins. "It was a trademark of his."

"He always inserted himself, embedded himself in the joy and pain that his subjects felt," adds National Geographic photo editor Nicole Werbeck, who worked with du Cille at the Post for a decade.In addition to his emotional investment, du Cille displayed physical stamina and courage. He had bad knees and a bout with cancer, but continued to work in conflict and disease zones. Yet, despite four decades of documenting the sorrows and chaos of human tragedy, du Cille remained good-humored and caring.

"Michel impressed me always with his gentle nature, genuine kindness, and enduring grace," says National Geographic photo editor Dennis Dimick, who knew du Cille at the Louisville Courier-Journal in the late 1970s.Werbeck remembers du Cille sitting with her one night at the Post in 2007, as she edited photographs of the assassination of former Pakistani Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto. He guided her through the grisly photos, she says. He made himself available to everyone as an adviser, colleague, and champion.

"Michel was an emotional anchor for a lot of the photographers and journalists he mentored," says Jenkins.The photographer had spent recent weeks in Monrovia, documenting the Ebola outbreak there. He took the above photograph of Esther Tokpah, 11, weeping as she is released from the treatment center on September 24. Though she recovered from Ebola, she lost both her parents to the disease.

"It is profoundly difficult not to be a feeling human being while covering the Ebola crisis," du Cille wrote in his essay for the Post. "Indeed, one has to feel compassion and, above all, try to show respect."—By Linda Qiu, photo gallery by Nicole Werbeck