The Nobel Prize’s secretive process and peculiar past

One of the world’s most prestigious awards, the Nobel Prize has a complicated history.

The Nobel Prize conjures images of inspired scientists, exemplars of peace, and meditative writers. While the prizes are well respected, a rich tangle of lore has grown around them since they were first awarded in 1901, driven in part by the secrecy inherent in the selection process.

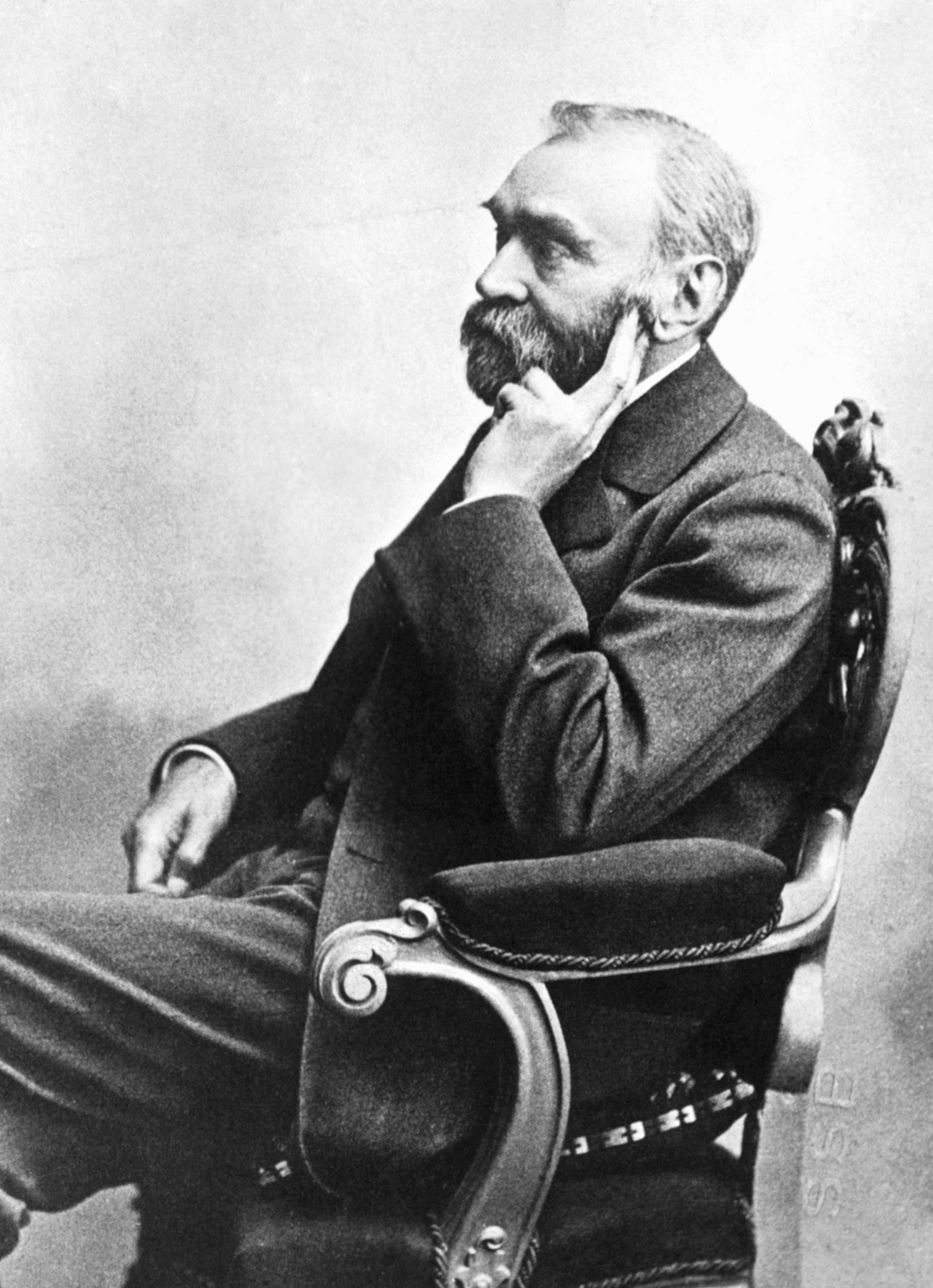

Intended to recognize scientists, artists, and diplomats whose work in the preceding year has “conferred the greatest benefit to humankind,” the prizes (each awarding 11 million Swedish Kroner, about $1.1 million USD) were established in 1895 at the bequest of Swedish inventor and businessman Alfred Nobel.

Though Nobel carried his rationale for each prize category into the grave, in life, he had a keen interest in physics, chemistry, medicine, and literature—four of the five original prize disciplines.

The fifth, for peace, is thought to have been inspired by his deep friendship with Austrian pacifist Bertha von Suttner. A sixth—the prize in economic sciences, was created by the Swedish National Bank in 1968 and named in memory of Alfred Nobel.

Some of the most famous recipients include Marie Curie and Malala Yousafzai, who was just 17 when she was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

From awardees who refused the prize to government opposition, here’s the surprising history of the Nobel Prize.

Nobel Prize categories and selection process

Several institutions are responsible for selecting laureates to receive the prize. The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences awards the prizes in physics, chemistry ,and economic sciences. The Karolinska Institutet selects laureates for physiology or medicine. The Swedish Academy picks the winner for literature, while a committee elected by the Norwegian Parliament selects the recipient for the peace prize.

The committees responsible for choosing prize recipients do so under strict rules of secrecy. Originally the proceedings were meant to be kept private forever, says Gustav Källstrand, curator of the Nobel Prize Museum in Stockholm and a Nobel history expert. Now, details of the process for each round of consideration are kept secret for only 50 years.

Strict adherence to the official rules has created some tricky situations over the years. For instance, despite the Nobel Foundation’s requirement that prizes be awarded only to living recipients, Canadian immunologist Ralph M. Steinman was posthumously awarded a 2011 Nobel for medicine.

(Who are the Nobel Prize winners? We’ve crunched the numbers.)

The selection committee had known he was dying of pancreatic cancer, but because the deliberations had to be kept secret, “they couldn’t keep calling to check in on how he was doing,” Källstrand clarifies.

The honor was announced on a Tuesday; unbeknownst to the committee, Steadman had died just three days prior. But because he had been alive when the prize was decided, the decision was allowed to stand.

Complicated history

Nazi Germany also created a number of problems for laureates—and even inspired a Peace Prize nomination for Hitler.

In 1939, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain was nominated to receive the Nobel Peace Prize for his role in negotiating the Munich Agreement, which ceded part of Czechoslovakia to Germany.

(The explosive origins of the Nobel Prizes)

In protest, 12 members of the Swedish Parliament put Hitler forward for the prize, claiming that if Chamberlain could be nominated for talking Hitler out of a war, then Hitler should be nominated for not starting one.

“Most people didn’t get the irony,” Källstrand explains. The nomination was withdrawn.

The war eventually started, of course, and Hitler forced three German scientists to decline their prizes during World War II. Richard Kuhn, Adolf Butenandt, and Gerhard Domagk did all ultimately receive their medals and diplomas, but not the cash, which can only be claimed for a year.

Domagk actually sent a telegram to the Nobel committee to thank them for the recognition. German secret police caught him, however. They imprisoned for a week and forced him to send a second message refusing the prize.

(Nobel laureates who were not always noble)

Previous laureates were not safe at the time, either. Since it was a crime to smuggle gold out of Germany during the war, the medals of physicists Max von Laue and James Franck, imprinted with their names and stored for safekeeping in Niels Bohr’s lab in Copenhagen, were clear evidence of wrongdoing.

As German troops marched in the streets of Copenhagen, chemist George de Hevesy stashed the medals in aqua regia, an acid strong enough to dissolve gold.

Incredibly, the beakers remained undisturbed through the war. The gold was precipitated back out of the solution and recast into new medals for von Laue and Franck.

In the past, Nobel committees have attempted to persuade uncooperative regimes to approve travel for laureates. When China refused to allow dissident and writer Liu Xiaobo out of the country to accept the Peace Prize in 2010, organizers set up an empty chair at the ceremony to make the point that Xiaobo hadn’t been permitted to attend.

(10 huge discoveries that should’ve been Nobel Prize winners)

Refusing the Nobel Prize

“Once the decision for a prize is made it can’t be revoked,” Källstrand says. “So when they give you the call, they’re not offering the prize, they’re telling you, you’re a laureate. Even if you say no, it doesn’t matter."

Such was the case for Jean-Paul Sartre, who declined his 1964 prize for literature, and Le Duc Tho, who declined his joint award of the 1973 Nobel Peace Prize with U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger.

(Your daily life is probably shaped by these 12 people—do you know their names?)

Award ceremony

The first week of October, when prize winners are announced in Sweden, kicks off a busy season that culminates with a lavish dinner at Stockholm City Hall on December 10, an event that is also broadcast live.

The end of award season isn’t much of an end at all. After Christmas break, the Nobel committees get right back to work, whittling down 2,000 to 3,000 nominations to choose the next cohort of history-making Nobel Prize laureates.