From Bali to the Berkshires: John Stanmeyer Comes Home

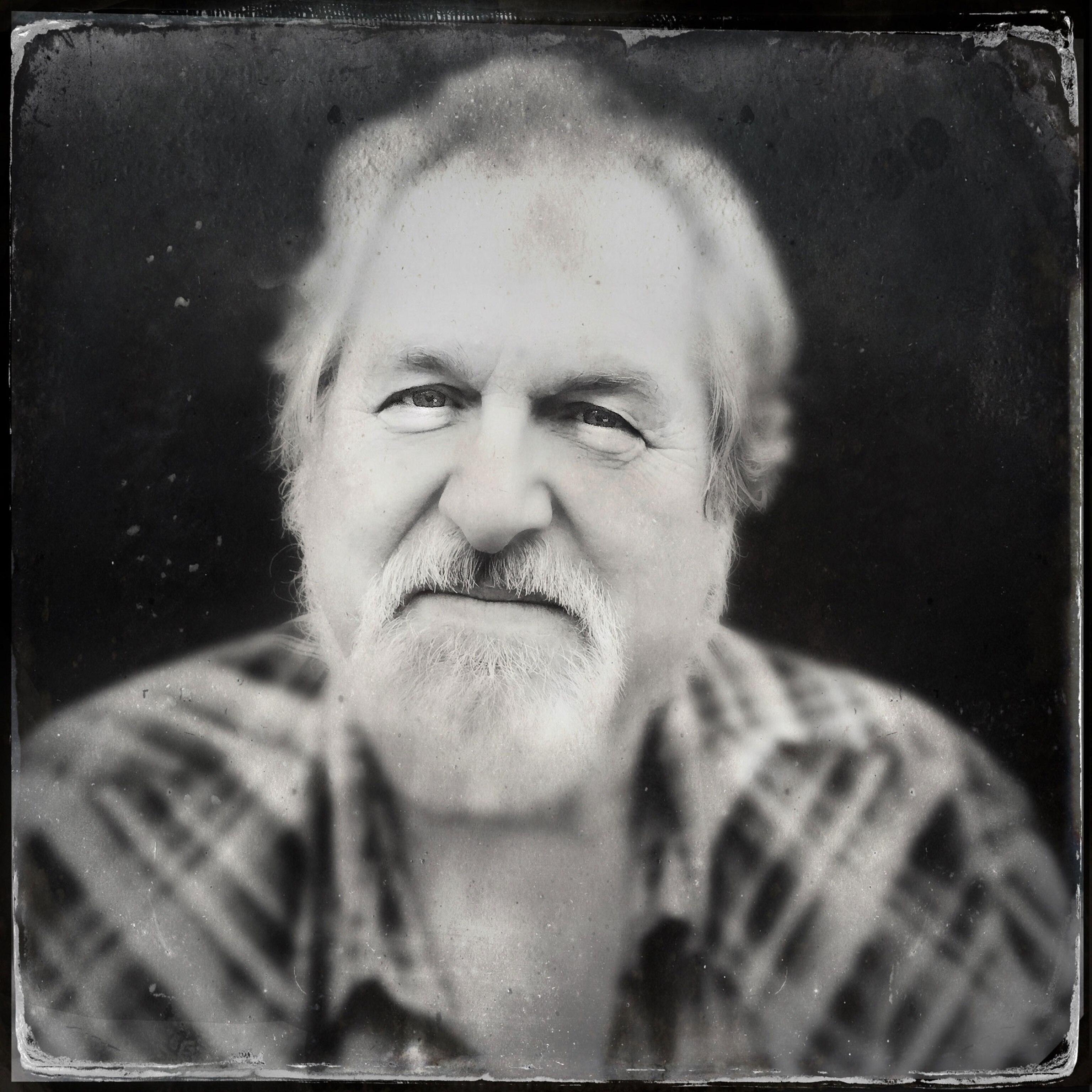

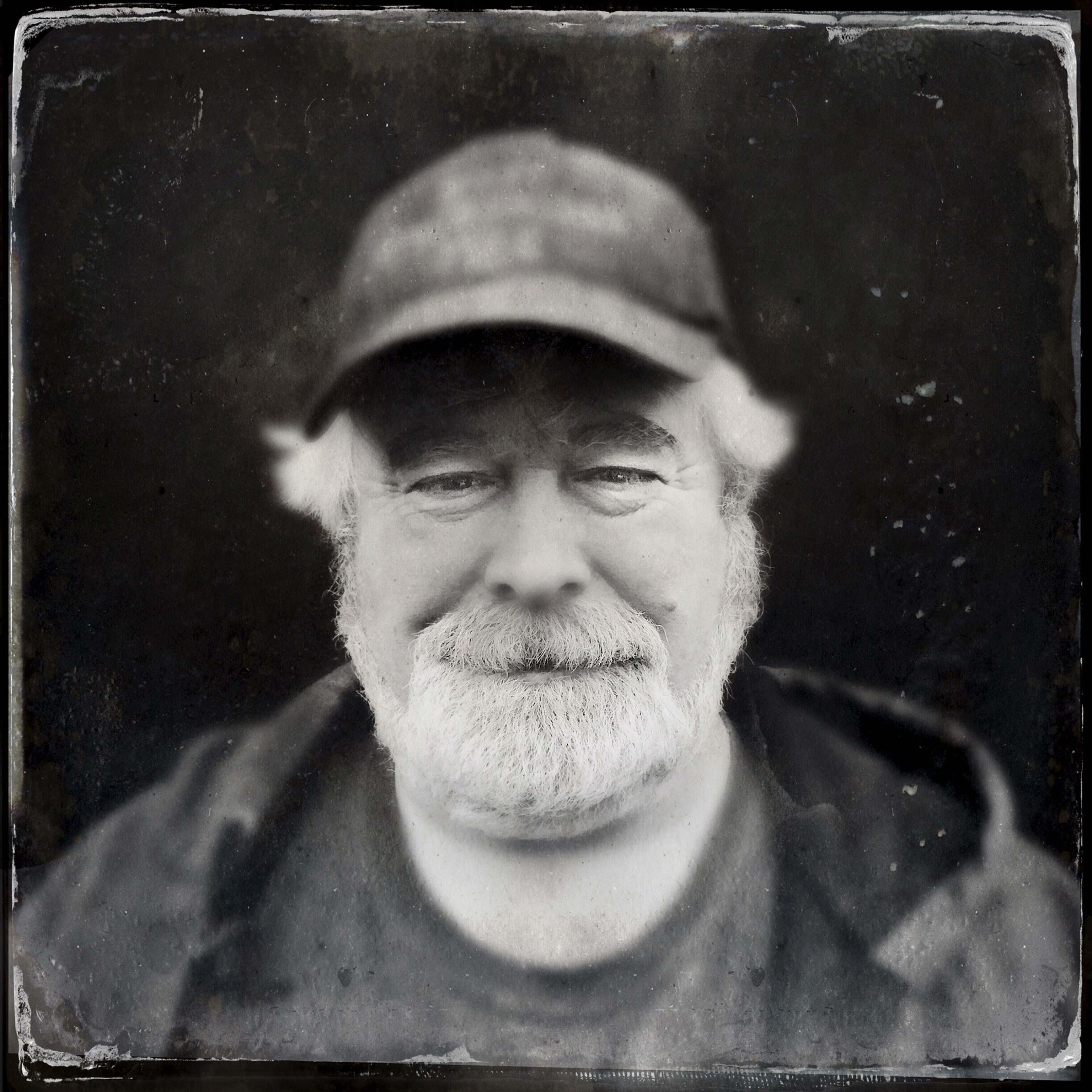

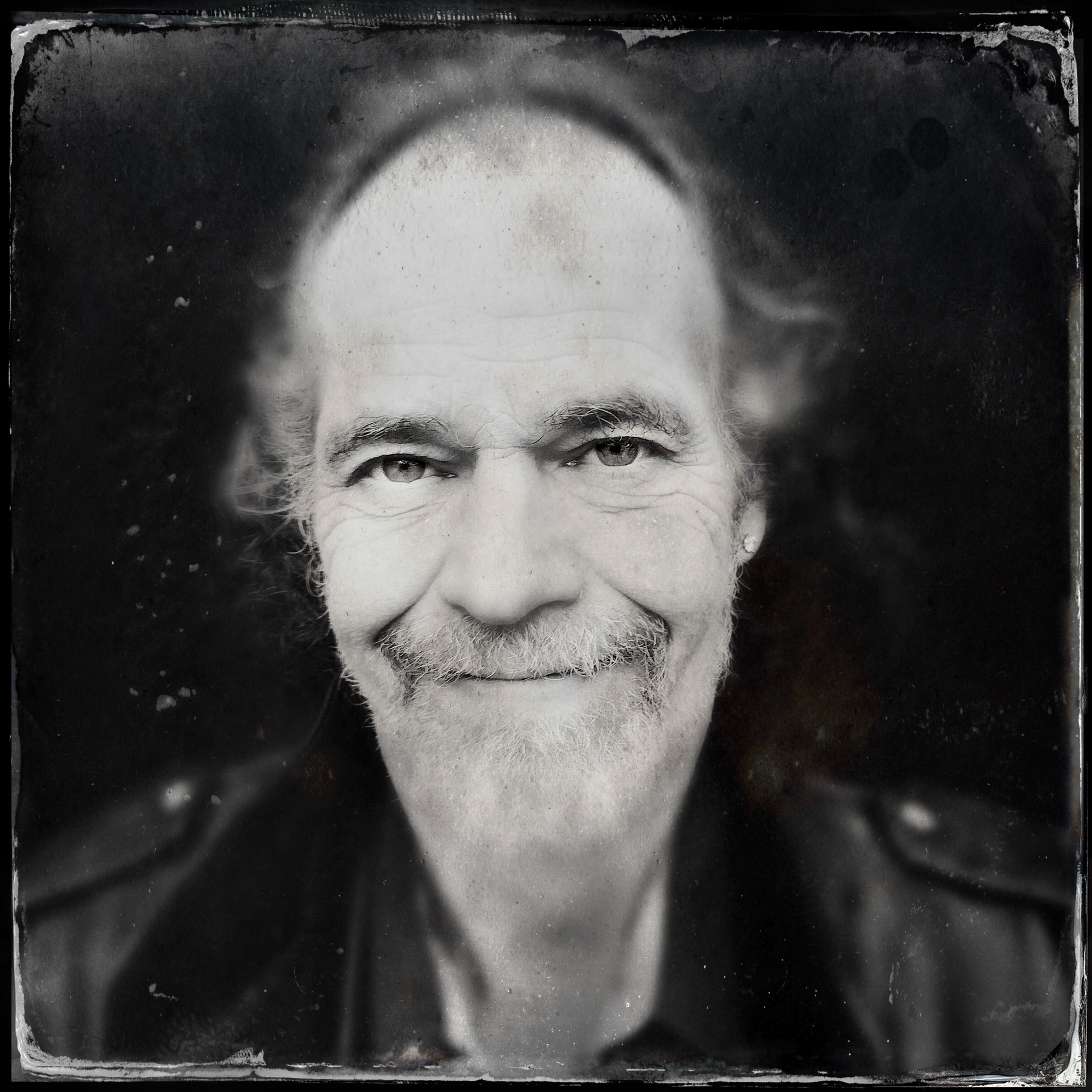

The National Geographic photographer welcomes you to West Otis and West Stockbridge, which embraced him as family.

Seven years ago, home was literally in the middle of a former rice field in Bali, Indonesia, and all around us were terraced rice paddies. After 12 wonderful years living in Asia, it was time to return stateside to help bring my wife, Anastasia, closer to her elderly father and to avoid numerous body-bending marathon flights back to the U.S. to work on stories at National Geographic headquarters, in Washington, D.C.

But where to live in a land I no longer knew?

On one editing trip to Nat Geo, I made a detour to upstate New York, meandering with a real estate agent around the town of Beacon, which a friend had recommended.

The homes all seemed to be placed one right next to another. I asked the agent: "Isn't there anything where one can have space? land? I'm from Bali, where the backyard is a thousand acres of rice fields. Surely there's countryside here?"

"Yes," she said eagerly. "The Catskills!"

"I've heard of that," I said. "Isn't there a song about the Catskills? Doesn't the Catskills seem 'dreamlike on account of that frosting'?'"

"No," she said, chuckling. "That's the Berkshires!"

"Oh—my confusion. Where are the Berkshires?"

"About 45 minutes farther north, in Massachusetts."

That Easter weekend in 2007, I made an overnight detour to Great Barrington, in the Berkshires. My GPS directed me past the house where Herman Melville wrote Moby Dick, along narrow, winding roads lined with trees as green as Bali. My path glided over history, and over majestic hills. It was snowing, and I was gobsmacked—the Berkshires were indeed dreamlike on account of that frosting.

I felt at home in a place I'd never been before. An energy seemed to emanate from the ground beneath me.

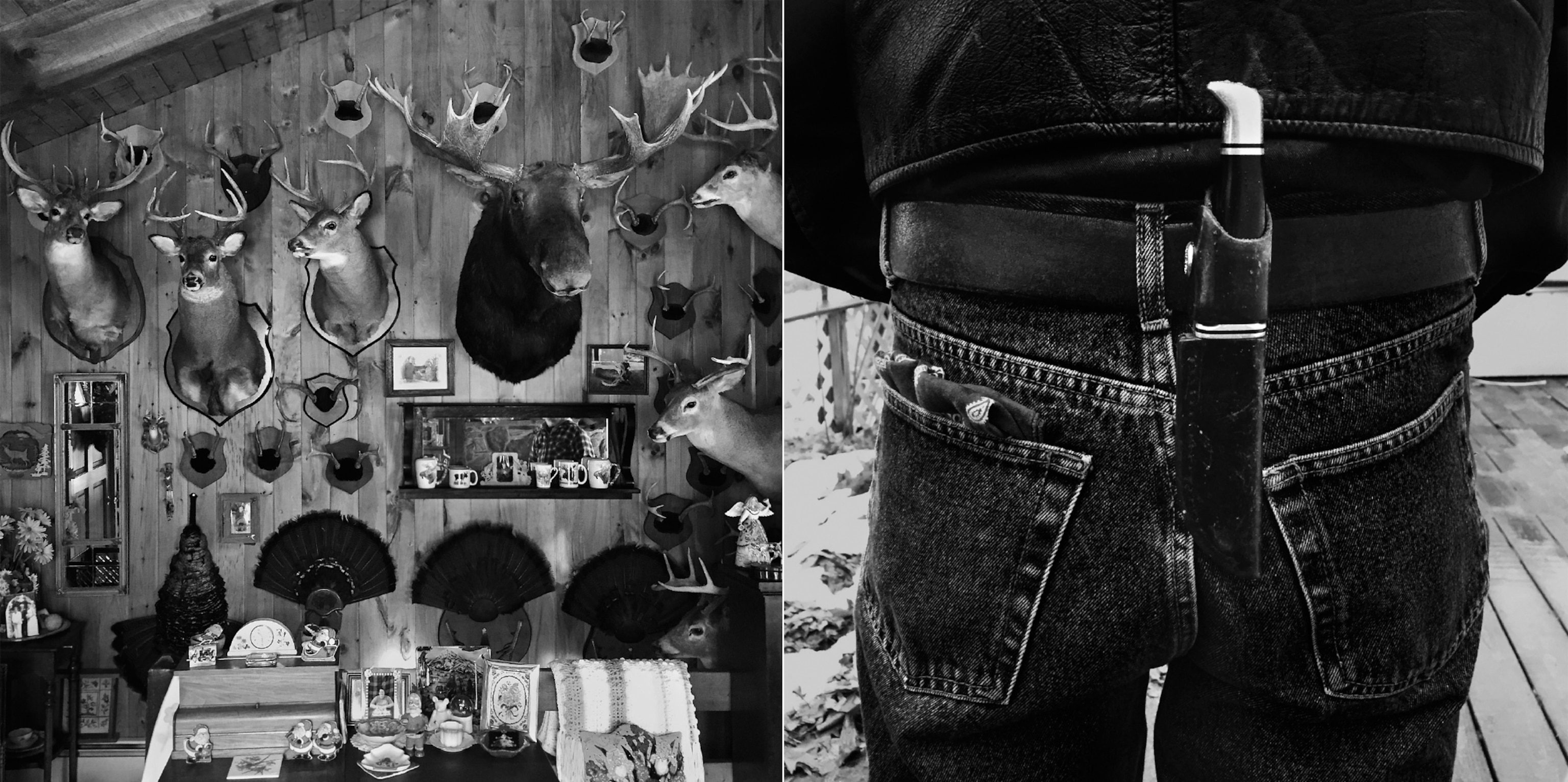

After three additional visits from Asia to the Berkshires, we settled one year later on a former horse and dairy farm in West Otis. A federal-style home hammered and pegged together in 1850, it fit our family of five well.

But the selling point was the land—and the barn, with a 4,000-square-foot loft. "Here's where you can store all the hay!" exclaimed our agent, twirling around like a dancer.

"I can barely take care of dogs!" I said. "This will be a photography gallery."

It takes more than a generation to become a local. As a newcomer to West Otis (elevation 1,220 feet), you're a "flatlander." As a flatlander, you're embraced and welcomed as if a relative, not fully a local.

Our farm is still known in Otis (locals drop the "West") as the Minery farm (the Minerys haven't owned it for nearly two decades). It will likely stay the Minery farm until my children's children (and maybe their children) come of age.

What draws many flatlanders to Otis is water. This area has more bodies of water than anywhere else in the Berkshires—rivers and lakes, puddles left millennia ago as ice retreated and melted.

During the past six years, the photo gallery in the former hayloft brought so many visitors to the farm that we lost our privacy. My photography needed a new home.

We found it in the village of West Stockbridge, just shy of 20 miles from West Otis. To say we adore Stockbridge would be an understatement.

It's here, in the little yellow house on Main Street called the Shaker Dam House, where I spend most of my days when I'm not on the farm or worlds away on assignment for National Geographic.

The house was once home to the manager of the historic Shaker Mill, still standing proudly today, and later to the overseer of the hydroelectric dam—the oldest in Massachusetts.

Downstairs is our coffeehouse and gallery. My photography studio is on the second floor, overlooking Main Street to the east and the Williams River, seen through a window of spectacular sunsets.

When something goes amiss behind the coffee bar, or we need to replace a lightbulb in the gallery, I walk one minute along the curb to Henry Baldwin's hardware store, said to be the oldest family-owned hardware store in the U.S. The Baldwins, whose forebears arrived in the mid-1800s, are fifth-generation Stockbridgeans. (Last year, Henry, a volunteer soccer coach at the high school, taught my son Richard how to play the game.)

In the Berkshires, people are genuine. At peace. Not thriving on desire for wealth. It's about balance. Family and community. The land.

John Stanmeyer was born in Chicago, grew up in the Bahamas, and went to art school in Florida. During much of the 1980s, he worked as an art and fashion photographer based in Milan, Italy. John then turned his camera toward social documentary photography and was drawn to the East. He lived in China for seven years, and Indonesia for five. Now John, his wife, Anastasia, and their three children, Richard, Konstantin, and Francesca, are firmly rooted in the Berkshires.