The Surprising Impact of 'Mountaineer's Guide to Death and Disaster'

The longtime editor of the American Alpine Club's annual report is retiring.

Every August, a slim, soft-cover book titled Accidents in North American Mountaineering arrives in the mailboxes of the 15,000 members of the American Alpine Club—the national representative group for climbers and mountain enthusiasts. The book, cleanly designed with its title in red, arrives neatly packaged with its sister publication, The American Alpine Journal.

The Journal captures the greatest triumphs of the year. Accidents reports its worst moments. Though little known beyond the world of rock climbing and mountaineering, Accidents, which has been published since 1943, is widely respected in these communities for its non-judgmental style and distinctive, clinical prose.

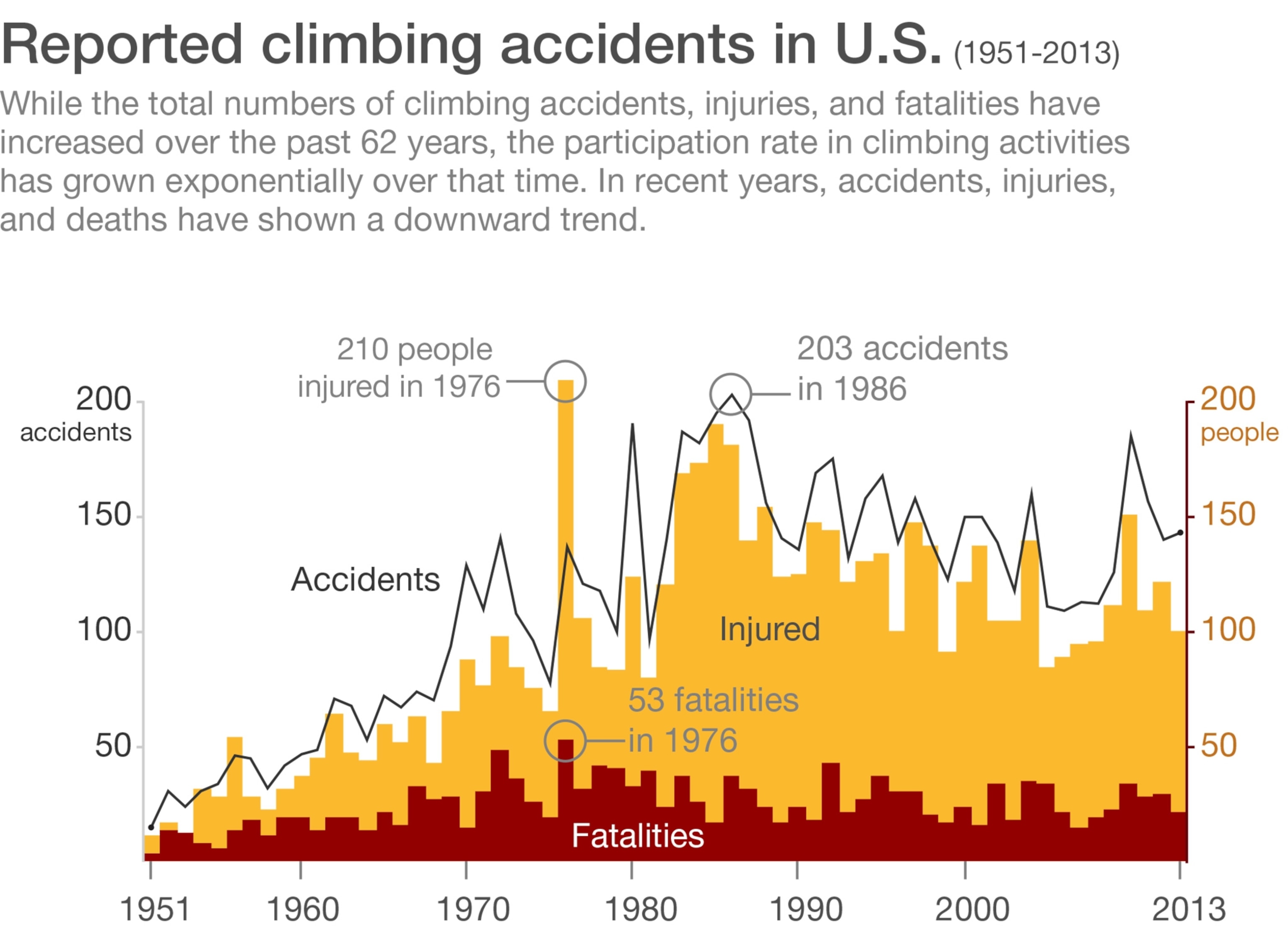

In 2013, the year most recently surveyed, Accidents in North American Mountaineering reported 143 climbing accidents in the United States and 11 in Canada among an estimated 300,000 active climbers in both countries. There were 25 fatalities. (Accidents covers technical rock, ice, and mountaineering incidents. Hiking and other general outdoor mishaps are not covered.)

The good news? Given the vast increase in participants, climbing is undeniably getting safer.

In 1974, by comparison, there were 31 fatalities in those two countries—but only an estimated 1,000 to 2,000 active climbers at the time. Because the publication doesn't just report accidents, but also seeks to analyze and assess them, it helps ensure the safety record continues to improve.

Last Saturday, at its annual gala in New York City, the American Alpine Club (AAC) honored John "Jed" Williamson, 75, who has held the position of editor, voluntarily and without compensation, for the past 40 years. (Full disclosure: My wife serves on the club's board.) The 2014 edition marked the end of his remarkable tenure. On Saturday, Williamson was invited on stage to receive a mock cover of Accidents, a publishing tradition.

The book has a loyal following among climbers. "I think people find it instructive and helpful, but also kind of fun—in a macabre kind of way," says Dougald MacDonald, executive editor for the AAC.

The Risk Consultant

At the gala, Williamson was in good—or rather, great company. The elite of the mountaineering community attended, from climbers Tommy Caldwell and Kevin Jorgenson, who received honorary memberships for completing the recent first free ascent of the Dawn Wall route on El Capitan in California's Yosemite National Park, to Reinhold Messner, arguably the greatest alpinist of all time and the event's keynote speaker. (Read why Caldwell and Jorgeson sanded and Super Glued their fingers for the climb.)

Williamson, for this part, came to the mountains in his youth as a cross-country skier and biathlete, and began working as a mountain guide in the Tetons in 1963 before settling in to a career in education.

Williamson helped establish outdoor education as a legitimate academic field—a course of study offered by hundreds of universities today. "Back then, you couldn't get a degree in 'canoe-ology,'" he says. "I'm living proof that an English lit major can get work."

He worked for Outward Bound and the University of New Hampshire before serving as president of Sterling College in Vermont. Along the way, he's also done "risk consulting" and serves as an expert witness from time to time, mainly in lawsuits involving climbing accidents and adventure programs.

Given his frenetic career, Williamson never suspected his editorship would last so long, but Accident's community-service mission and the changing nature of climbing kept him engaged. During his lifetime, climbing has been radically transformed by technology and demographics. More sophisticated equipment and better techniques made it possible for the accident rate to fall, even as the number of climbers increased dramatically.

"Over the last 40 years, we went from pitons to nuts to cams to sticky rubber shoes," Williamson said Saturday. "The nature of climbing was changing, and so were the accidents."

Educating Climbers Through Stories

The heart of the publication is the "Accidents & Analyses" section, a collection of case studies of the most "noteworthy" accidents of the year. (You can search every incident ever published in the book.)

"The idea wasn't just to record accidents," Williamson explains. "The idea was to say, 'What will let people learn from this?' People don't learn from tables; they learn from stories."

The 2014 edition contains incident reports with such titles as "Stranded—New and Unexpected Situation, Exceeding Abilities" from Yosemite National Park, and "Inadequate Equipment—No Sunglasses, Snowblindness" from Mount Rainier in Washington.

Many of the reports are written by search and rescue professionals like federal rangers or avalanche forecasters, but victims are invited to contribute their own accounts. Though some are reluctant to publicize their misfortunes, the typical response is overwhelmingly supportive.

"They can be anonymous if they want to be," Williamson says, "but there are also people who have come forward with great humility and insight, and in my opinion those are the absolute best case studies."

"I'm blown away by some people's willingness, even enthusiasm, to get the story out about their f***-ups," says AAC editor MacDonald, who is currently editing the publication.

Each entry is broken down into a description of what transpired, followed by an analysis. Although many accidents are the result of technical blunders by beginner climbers, or simple forgetfulness by more experienced hands, the simple fact of cataloguing them sends a powerful message.

"We benefit every year from the reminder that simple mistakes have great consequences," says Phil Powers, the AAC's executive director. At the popular Shawangunks area in New York, for instance, Accidents reports 17 incidents in 2013: Seven resulted in serious injuries, and ten yielded sprains, strains, and other minor ailments. There were no fatalities.

"One of the things I have tried to avoid is using language like, 'This guy was a real dummy,'" Williamson explains. "Any time I get a call from a sheriff's office laying blame, that doesn't serve to help educate people."

But "if they call themselves a dummy," he says, "that's fine."

How to Avoid Mistakes

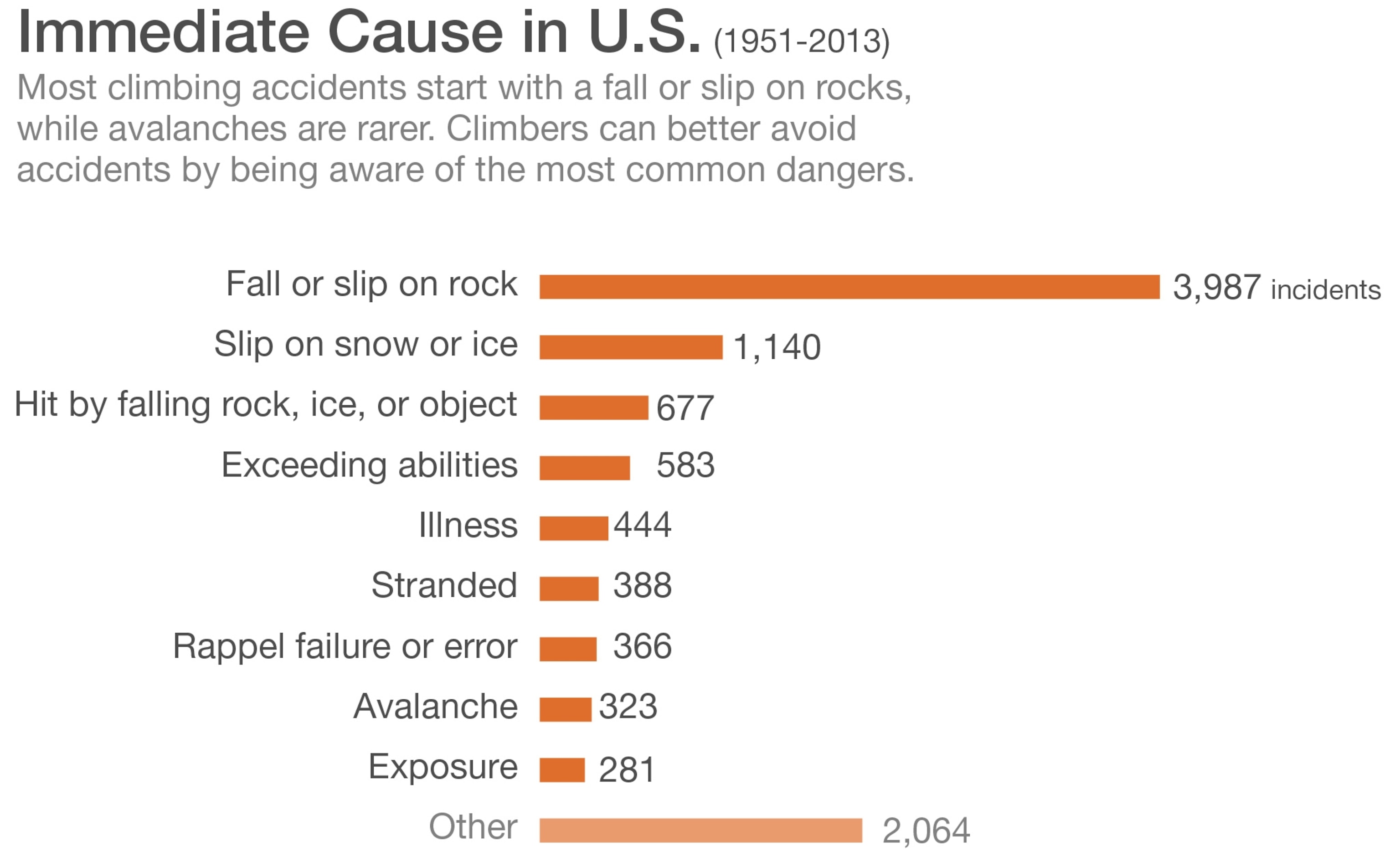

Collectively, the stories in Accidents illuminate patterns and trends. "People will often say, 'The majority of these accidents happen to inexperienced climbers,' but that's not the case. The majority of accidents happen to experienced climbers," Williamson says.

After 40 years of reviewing accidents, Williamson knows the most common mistakes climbers make. He points to several mental traps, factors that might distract a climber from looking at a situation from a safety-first perspective.

One is trying to please people. Another is feeling tied to a self-imposed schedule. Both of these points might apply to a guided party that included several Iraq veterans on New Hampshire's Mount Washington. The group continued despite being warned by a ranger of the risk, and three of the climbers were swept away by an avalanche (they were later rescued).

The most climbing fatalities ever occurred in 1976—the year of the U.S. bicentennial, when many inexperienced teams attempted ascents of Mounts Denali and Rainier in honor of the occasion.

"A lot of accidents happen to experienced climbers simply because they are rushing to try to make it to the restaurant on time," Williamson says. He's considering writing a book that would condense his knowledge into easily digestible lessons.

As for the publication he has done so much for, Williamson hopes it won't change too much. "I hope that the continuing focus is on case studies, and I hope it doesn't fall in the trap many magazines have fallen into. Some publications have so much distraction going on each page," Williamson says.

"There's a curious similarity to climbing, because one of the causes of accidents that has increased is distractions," he continues. "One of my favorite recent accidents was a kid who was texting while belaying. He thought his partner asked for tension, but really he called for slack—and he pulled his partner off!"

Freddie Wilkinson is a writer and climber based in New Hampshire. Read his National Geographic

account of climbing in Antarctica's Queen Maud Land

.