Witnessing War's Horrors Through a Camera Lens

When Lynsey Addario started out, journalists were respected as neutral observers. Now you can be beheaded.

Growing up in a large, Italian-American family in Connecticut, Lynsey Addario had no idea that her job would one day take her to some of the most dangerous places in the world. But a trip to Argentina in her 20s opened her eyes to the wider world and made her curious to see more. As a photojournalist, she went on to cover war zones from Iraq to Syria to Afghanistan for numerous publications, including National Geographic, where she is one of our Women of Vision.

From her home in London, the author of It's What I Do: A Photographer's Life of Love and War, talks about how she copes with fear, why becoming a mother has not deterred her from working in war zones, and how the rise of the Islamic State (IS) has altered the calculus of risk.

You say, "Few of us are born into this work. It's something we discover accidentally." How did you become a war photographer?

It was a gradual process. I think a lot of it had to do with curiosity and working overseas. Shortly after I graduated from university, I moved to Argentina to learn Spanish. While I was there, I went into a local newspaper and sort of begged for a job. In university I'd been studying international relations, and I thought photojournalism could be a marriage between international relations and art: telling stories with pictures. They said no, but I talked my way in.

Eventually I moved to New York and worked for the Associated Press, but I always wanted to move back overseas. So I moved to India and started covering some women's issues. I had a roommate, and one day she said, "You cover a lot of women's issues; you should go to Afghanistan under the Taliban."

I never thought of myself as a war photographer. It wasn't what I set out to do.

I was 26, and there was very little that intimidated me, so I said OK. I saved my money, and I went to Afghanistan under the Taliban. That was the first time I'd been in a place where there was no American embassy. It was a war zone. I spent time documenting women's lives, running around with my cameras in a bag, even though photography was illegal at the time.

Later, I went back for the fall of the Taliban and Kandahar, and when the war in Iraq was brewing, I geared myself up to go. I felt if American troops were going, I wanted to be there and see what was happening. It was really curiosity more than anything—a feeling that I wanted to be on the front lines of history, though not necessarily the front lines of combat. Eventually, everyone kept referring to me as a war photographer, which was initially very confusing, because I never thought of myself as a war photographer. It wasn't what I set out to do.

Addario is an Italian name. Tell us a bit about your childhood and how it shaped your career choice.

I was raised in a big Italian family. I have three sisters. My mother and father were married until I was about eight years old. Then my Dad came out of the closet and left with my mother's then very close friend, Bruce. They've been together for almost 35 years. So my household was always very open and fun, with very few rules. My parents always encouraged us to be creative and to do what we loved and never put limitations on ourselves. I think that was the fundamental reason why I felt comfortable going to unknown places. They never really instilled fear in me. And they always taught me to respect people and be open to different kinds of people. For me, that is a very important quality for a journalist to have.

Robert Capa once said, "If your pictures aren't good enough, you're not close enough." Is that your philosophy?

It is, but not necessarily in combat zones. No matter what kind of story you're trying to tell, you have to get in there and be very intimately involved with your subjects. You have to care. Sometimes I meet photographers who don't have that empathy, and I wonder how they can make good pictures. I think it's very important to get close emotionally and physically.

Most stories I do involve a lot of preliminary research—finding the people I want to spend time with, interviewing them, making them feel comfortable. I only start shooting hours later, if not days. I'm not the kind of photographer who walks in with my camera out and just starts shooting away on the motor drive. [Laughs] It's a process that takes me a while. I think of myself as a pretty slow photographer.

How is it being a woman in what is still a mostly male-dominated profession?

I find it an advantage. I work mostly in the Muslim world. Society is segregated, so I have access to women as well as men. Physically, there are challenges. I remember we did this seven-hour patrol through Kandahar, into the opium area. We knew we were going to get ambushed by the Taliban, and every 200 to 300 feet or so, we had to jump across a ten-foot-wide irrigation ditch. [Laughs] I'm five feet tall. My colleague, Dexter Filkins, whom I was embedded with, would jump across before me and then reach out his hand halfway over and literally pull me across. But I don't want to be the kind of photographer who holds up the rest of the troops because I'm a girl.

How do you deal with fear?

In a situation like that, there's no place to put it. When you're threatened with execution, for me, I go into a kind of Zen state, a place where I just try and stay very calm. I don't scream and shout. I just say, Well, it's my choice to be here. I'm a journalist, and I've made this decision to cover this war, and this is one of the consequences. It's about trying to just keep it together. That's not to say I didn't break down many times throughout the six to seven days we were in captivity in Libya.

Have you ever not taken a photo because it's too dangerous—or horrific?

There are a lot of pictures I haven't taken because it's too dangerous. There are times when I think that the front line is too dangerous, and I'll pull back. I don't shoot gratuitously gory pictures of someone who's been killed, or someone who's gravely wounded. I'm obviously trying to show the toll of war. But I think it's very important to be respectful of your subjects.

Anthony Loyd, the British war correspondent, once said of being in Bosnia that he felt like a "war pornographer, a voyeur." Have you ever felt that?

Yeah. I often do. My philosophy has always been that I'm there for the people I'm covering. I'm just a messenger documenting whatever is going on and bringing their message to people in power who may be able to do something about it. Whether it's pornography or whatever you want to call it, I'm walking into very, very intimate scenes and people's most vulnerable moments. That's something that, as I get older, I'm much more wary of and try to ensure that everyone I'm photographing feels comfortable with what I'm doing.

One of my favorite photos is of a group of U.S. Marines shaving in the desert in Iraq. Set the scene and describe how you win people's trust.

That was actually one of the easiest. They'd just gone into Tikrit, Saddam Hussein's hometown, and they were celebrating. It's much harder to photograph soldiers when they're losing or when they've just lost one of their comrades. I took this photo a few days after Saddam Hussein fell. We were waiting in a huge convoy of journalists to get into Tikrit, and the Marines were right in front of Saddam's palace. They'd fought their way from Kuwait, so they were thrilled to have a moment to shave and do a bottle bath. There's something nice about seeing someone from your own country when you're in a war zone. So it was really exciting to come upon a group of Americans and be like, "Hey!"

You describe listening to a Pakistani woman enthuse about 9/11. How do you separate your identity as a professional—and an American?

I remember that moment very distinctly. I'd never heard that before, so for me it was so eye-opening to listen to someone and try and find out where she was coming from. I wanted to understand what inspires such hatred that you would fly airplanes into the World Trade Center. I try not to bring my own prejudices to things. Even if I have them, when I'm working, my job is to write down what everyone says, to document what they say and publish it. I didn't feel offended at what she was saying. I was curious about where it was coming from.

In the old days, you had to send your pictures out by courier. Or, like Robert Capa, lose them in a suitcase. How has technology transformed your work as a war photographer?

[Laughs] It's so funny because I am sitting here this afternoon looking at pictures I shot on negative. They're horrible quality because I used to have to get them developed at local labs in Pakistan, where most of the chemicals were expired. They would just scratch the hell out of the negatives. So most of the pictures from those days are completely trashed. But I'm grateful I learned on a camera with film because I got a much better sense of light. Now, with digital, I can shoot and file within minutes. If you're working for a newspaper, you have to get the pictures out immediately.

How did the deaths of Chris Hondros and Tim Hetherington affect you?

I'd been kidnapped in Libya. And when I got out, I felt we were so lucky to have survived. There were so many times we could have been killed. But I felt emotionally pretty stable. Then Tim and Chris were killed almost exactly a month after we were released. I was in New York, having meetings and spending time with friends and family. When I found out they'd been killed, it was as if the trauma I had never suffered after Libya hit me. I don't know if it's survivor's guilt. But my first thought was, "How could they have been killed when we lived? That's not fair." It took a week for me to stop crying pretty much all the time.

There are not that many people who have covered the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and we all know each other pretty well. The night they were killed a big group came together at the Half King, a bar in Chelsea [in New York City] owned by Sebastian Junger. We just cried and hugged. And I think that feeling of camaraderie really helped. I've had many close friends my whole life, but I really gravitate toward my colleagues because my colleagues can understand the way I feel. At this point in our careers, many of us have lost friends and had friends lose a leg. It's something we can understand in a way that people outside the profession have a harder time understanding.

You've spent much of your life witnessing cruelty and horrors. What have been the emotional and psychological costs? Do you have any ideals left?

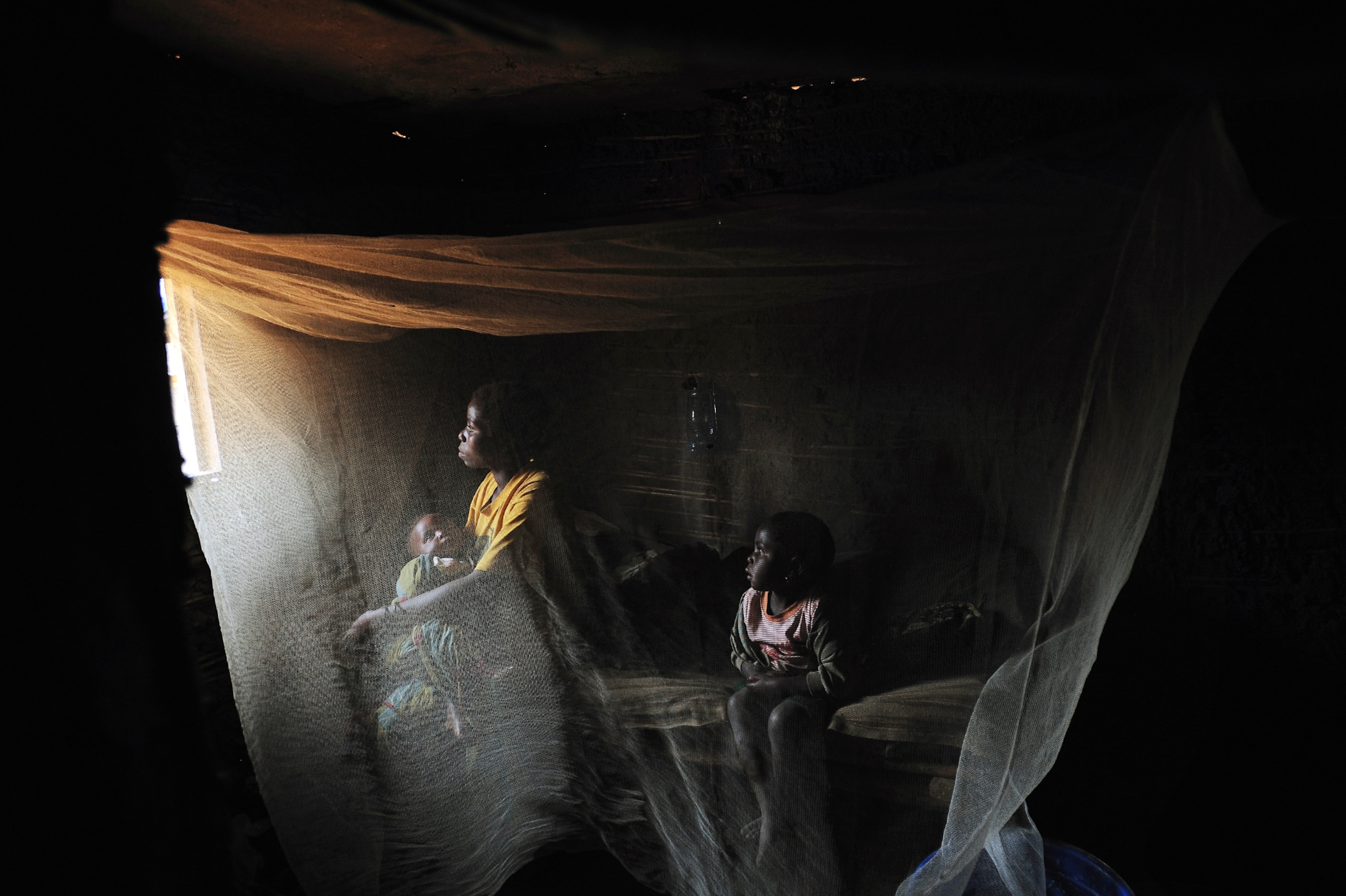

I do, actually. Because in those miserably dark places, I've found the most astonishingly resilient and generous and loving people. In war, one sees extremes in character. I've seen the most evil people, and I've seen the most unbelievable people.

In those miserably dark places, I've found the most astonishingly resilient and generous and loving people.

I remember in Libya, when we were working along the front line, one of the families gave us a house in Brega to sleep in. There were 17 journalists sleeping on the floor of this house. The locals were so grateful to us being there to cover their side of the story that every night at 6:00 p.m. there would be a knock on the door. They sent their ten-year-old son with two giant trays of food for us. Moments like that are when you see an incredible side to people who are trapped in war. That doesn't happen in many other places because there are so many other distractions in everyday life.

So I haven't lost faith at all. In fact, before I go through something personally, I think of the women in Africa who live with nothing, who have been through so much hardship, yet they still laugh and smile all the time. These people have taught me so much over the years.

Since you wrote the book, a new, even more deadly, foe has emerged in the Middle East. You've also become a mother. Has the spate of beheadings by IS deterred you from reporting on them?

The question that I get all the time is, Now that you've become a mother, do you still do this work? I roll my eyes because, yes, I still do this work! Of course, every time I almost die, or a friend loses his life, I have to pause and reevaluate how I can continue to do this work in a way in which I can stay alive.

IS has changed the dynamic 100 percent. When I first started out, journalists were respected as neutral observers. In 2004, we were kidnapped by a group affiliated with al Qaeda. But they let us go when they ascertained we were journalists. Now you can get beheaded for doing your job as a journalist.

So every assignment, I have to weigh where am I going, what is the story I'm covering, what can I contribute to that story, and how close am I going to be to IS. The last time I was in Iraq, I couldn't get a straight answer from the peshmerga fighters where the front line was. Almost as a joke, I'd say, "OK, so where is IS now?" "Oh, they're that way." "Well, no—I want to know where they are. Not a direction!" [Laughs]

In my 20s and early 30s, I felt invincible. I hadn't lost friends. I hadn't been kidnapped twice. Motherhood has made me realize that I need to stay alive. I have this tiny little person who's depending on me. I'm more cautious. I don't go right to the front line. I cover the same places and the same stories, but I try and stay back a little bit. But am I giving up the work? No! Will I give up the work? No!

Simon Worrall curates Book Talk. Follow him on Twitter or at simonworrallauthor.com.