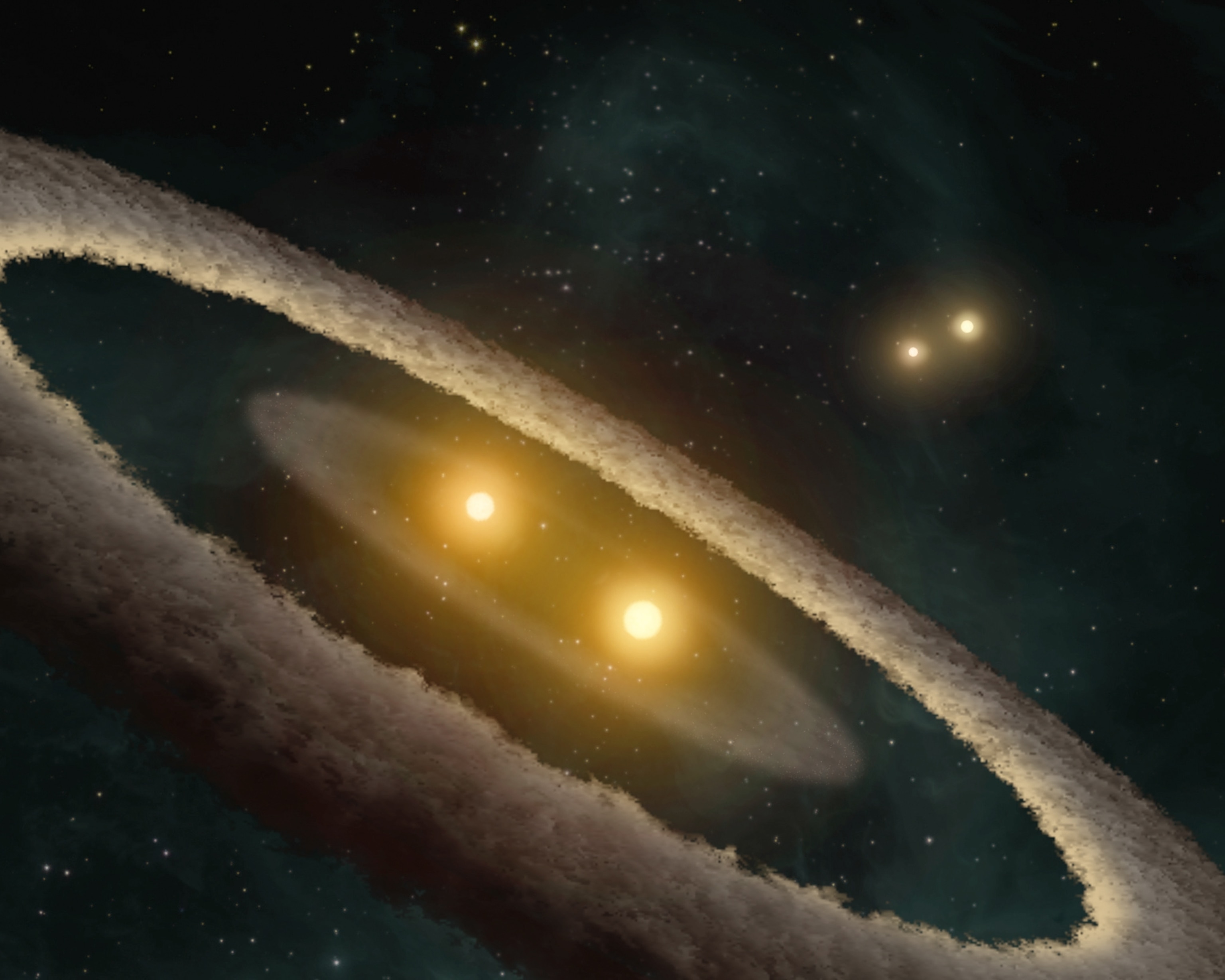

Multiple-Star Birth Revealed in Stellar Nursery

Quadruple-star system will emerge in 40,000 years.

Astronomers have have gotten their first good look at the beginnings of a quadruple-star system.

The discovery could lead to a better understanding of why some stars, such as our sun, are loners, while many others are born into systems with two, three, or more stars.

Using the combined power of two of the largest radio telescopes in the world—the Very Large Array (VLA) radio observatory in Socorro, New Mexico, and the Green Bank Telescope in West Virginia—along with the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope in Hawaii, a team of international scientists have observed the earliest stages of formation of the future four-star system.

The study, published February 11 in Nature, describes a cloud of gas called Barnard 5, or B5, located some 800 light-years from Earth in the constellation Perseus. Nestled within the stellar nursery, a core of gas, scientists found one young protostar and three dense pockets of matter that they believe will collapse into stars in about 40,000 years—a blink of an eye in astronomical terms.

All four stars won't stay together forever, though, the astronomers predict. Eventually at least one of the stars will get ejected, computer models show, leaving behind three that may gravitationally bind together to form a triple-star system.

"These kind of multistar systems are quite common in the universe. Think of Tatooine in Star Wars, where there are two 'suns' in the sky," said co-author Gary Fuller of the Jodrell Bank Centre for Astrophysics at the University of Manchester in England. "That isn't too far away from something that could be a real formation. In fact, nearly half of all stars are in this type of system."

Our nearest stellar neighbor, Alpha Centauri, located a mere 4.37 light-years from Earth, is a binary star system.

While multiple-star systems may be close, and common across the Milky Way, exactly how they form has been a long-standing mystery.

But since most stars appear to be paired, the bigger mystery may be the birth of our own singular sun five billion years ago. Until now, the only hint pointing to its cosmic hermit status has been the distribution of the solar system's planets—which suggest we were never part of a multiple-star system.

These new findings add another critical piece to that still unsolved puzzle.

See for Yourself

Since multiple-star systems are considered so common across our galaxy, its not surprising that there are many fine examples visible to the backyard sky-watcher.

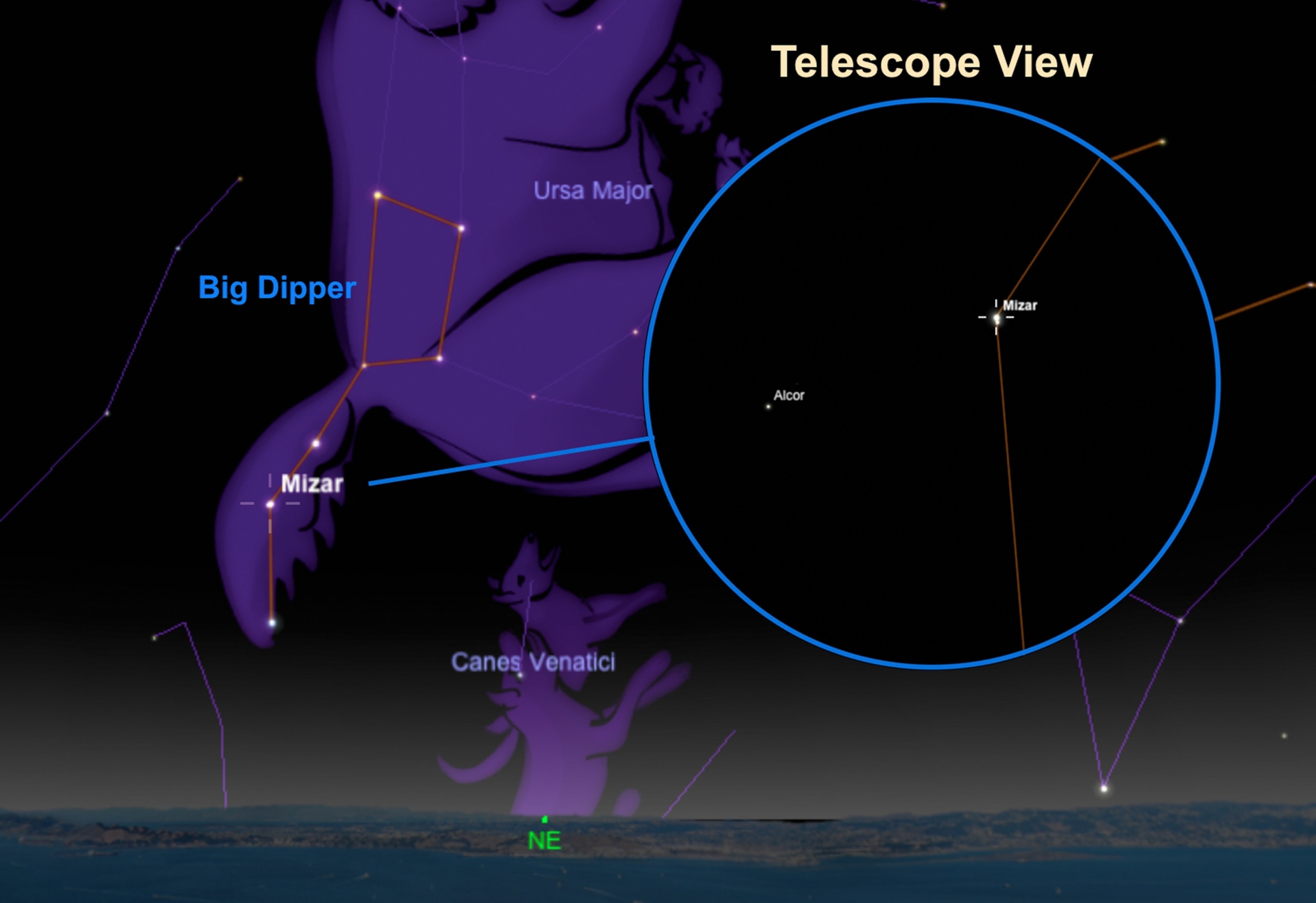

One of the easiest binary or two-star star systems to spot in the Northern Hemisphere is in the famous Big Dipper stellar pattern, in the constellation Ursa Major, the Great Bear.

Face the northeast sky after nightfall and look for curved, three-star handle attached to the bowl.

By far the most celebrated star in this brotherhood of the bear is Mizar, located in the middle of the handle. It's claim to fame is its association with a much fainter companion star, Alcor.

Known affectionately as the Horse and Rider, Mizar and Alcor are an eternal favorite for backyard astronomers with binoculars and telescopes and have traditionally been considered a good test for the naked eye. Ancient Persians are said to have used the ability to see Alcor as a simple vision exam—called the "test," or the "riddle"—for apprentice hunters. Can you see the pair on a clear moonless night ?

Too far apart to be orbiting each other, faint Alcor's appearance close to Mizar is merely coincidental. The two stars are separated by more than three light-years, forming an optical binary. Pointing a small telescope at Mizar, however, will reveal a much closer, true companion.

First sighted in 1650, this faint companion sun is now known to orbit Mizar every 10,000 years. Detailed observations have indicated that the Mizar system may be composed of more stars and could even be a remarkable quintuple-star system. Little Alcor, meanwhile, is a true binary in its own right.

Cosmic Unicorn

Within reach of small backyard telescopes is one of the skies finest true triple-star systems—Beta Monocerotis. You can hunt it down within the dim constellation Monoceros, the Unicorn, riding high in the southern sky just after darkness falls.

At magnitude 3.9, Beta Mon is just visible to the naked eye from city suburbs as a faint star to the left of the three belt stars of Orion.

A small telescope will resolve Beta Mon into three blue-white stars, very close in brightness, that form an acute triangle. Located some 690 light-years from Earth, this close triplet circles each other.

Happy hunting!