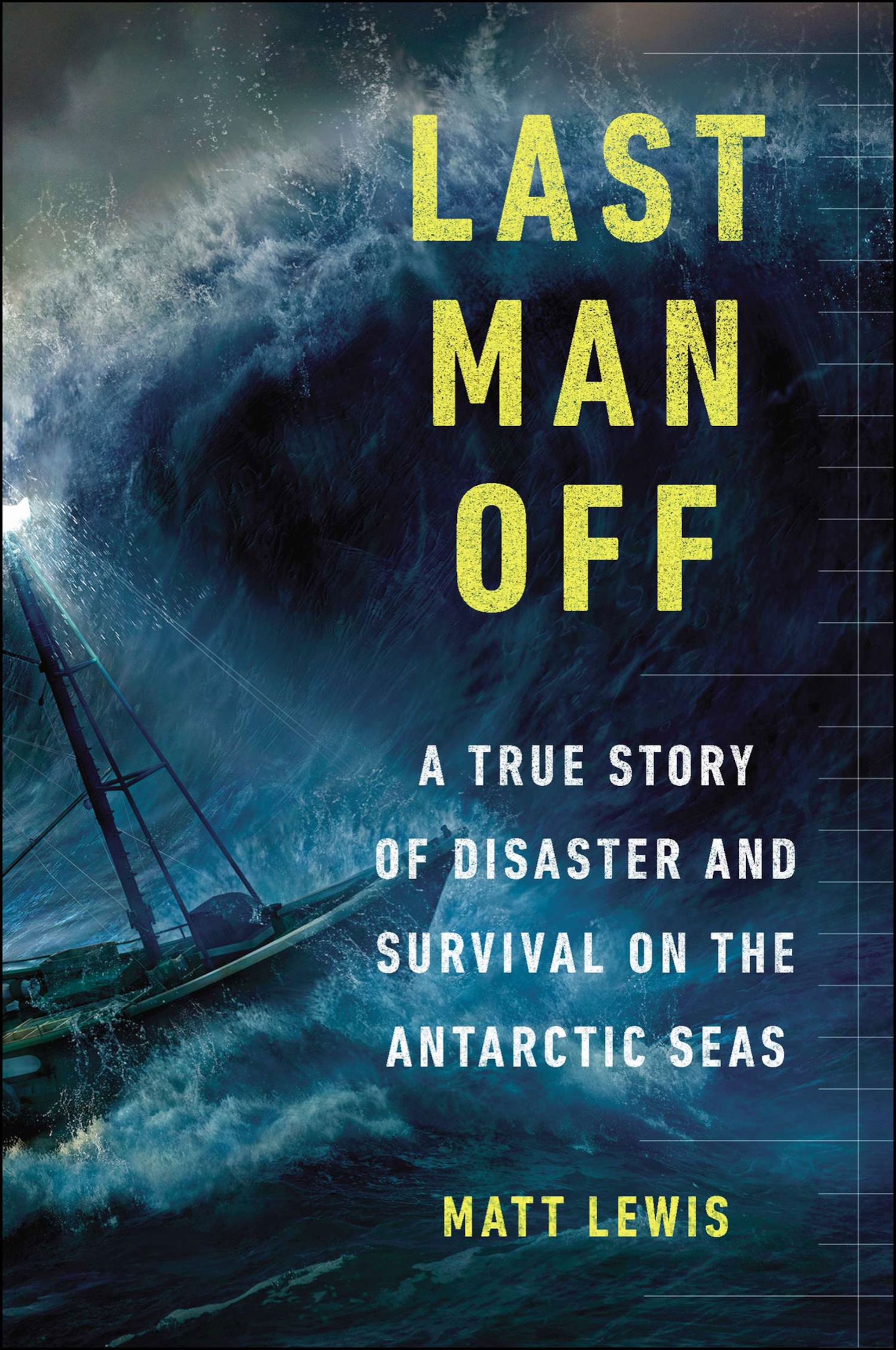

Life, Then Death, on a Trawler in Freezing Antarctic Seas

When the boat sank 170 miles from land, the author survived despite a leaky life raft, sub-zero waters, and waves so high they cast shadows.

Matt Lewis, a British marine biologist and author of Last Man Off: A True Story Of Disaster and Survival On The Antarctic Seas, was only 23 when he was hired as a scientist on the South African fishing trawler, the Sudur Havid. Destination: South Georgia Island, in the Antarctic, to fish for one of the most valuable catches on earth, Patagonian toothfish. Three weeks later, he found himself in a perfect storm which left many of his crewmates dead.

Talking from his home in Aberdeen, Scotland, he describes why long-line fishing is one of the major causes of albatross deaths; what it was like being in a life raft with 17 men, ten of whom died; why malpractice and a desire for profit caused the tragedy; and how naming his daughter, Camilla, brought some closure to his ordeal.

It took eight years for you to decide to write this book. Why did it take so long?

For a long time I was just trying to get on with my life: keep calm and carry on, and pretend to myself that nothing had happened, therefore I had no story to tell. I had different jobs in different places, but I didn’t tell people about the accident. It’s not natural pub conversation Then, about six years after the accident, I decided I wanted to start writing.

How did you end up on the Sudur Havid. And what were your duties?

They needed to have a scientist, an independent observer on board, as a condition of their license. I’d been given the choice between two vessels, and I chose the Sudur Havid because it had English-speaking officers. I flew down to Cape Town and joined her there and we sailed down to the Subantarctic, right down to the island of South Georgia to start fishing.

Underwhelming might be the one way of describing the first time I saw the boat. The other boat I could have been on, her sister ship, the Northern Pride, was a lot bigger and nicer. I’d chosen the small, older rust bucket [Laughs].

You were the only Brit on board. Describe the crew’s ethnic make-up and the tensions among them.

The officers were mostly South African. A lot of the crew were either Ovambo from Namibia or Xhosa from South Africa. There were also a lot of Cape Coloured guys, a German engineer and an Icelandic captain. He was just there for his safety certificate, though. He was shoved in his cabin and told to come out only for night duty. So he wasn’t actually in charge of the boat.

Because a lot of the crew were Afrikaans speakers, English was a second or third language. So they called me “Englishman.” [Laughs] “Englishman, come over here”, “Englishman, get out of the way!” “Englishman, you’ve brought us bad luck, we’re not catching any fish!”

You ended up fishing on the other side of the world in the ‘Roaring Forties’. Give us a picture of that environment.

We were even further south than that. We were into the 50s’ in latitude, which are known as the ‘Furious Fifties’. We were almost as far south of the equator as I am north here [in Aberdeen]. We were fishing in the tropic winter, in June, and temperatures on deck were normally just at or below freezing.

On the day we hit trouble, Klaus, the engineer, told me the water temperature was minus one. For most of the voyage, we had a mixture of calm days when we were actually able to turn the engine off and just drift along. But the day we hit trouble, you’re talking about ten meter [33-foot] high swells. The chimney pot on the top of my two-storey house is ten meters up. So you can picture a wave that’s that size or bigger.

On the sixth of June, we woke up to the roughest conditions we’d faced.

Your target was a fish you describe as “an abyssal cruise missile with a toothy grin.” Introduce us to the Patagonian toothfish aka the Chilean sea bass.

I call it an abyssal cruise missile because he’s cruising through the ocean’s abysses. Most of the toothfish we were catching were about the same size and weight as your thigh. Some were up to 60 years-old, two meters in length, and maybe 100 kilos [220 lbs.] in weight. They are enormous fish, a dull grey or a brown color. Their biggest feature is their mouth. It’s full of razor-sharp, backward-pointing teeth which are designed for grabbing hold of prey. If you were grabbed by that mouth, there’s no way you could escape.

Long-line fishing is also the major cause of albatross fatalities. Did you see evidence of this?

Long-line fishing uses a long rope, about 15 miles in total, baited with 14,000 hooks. The hooks are about three to four inches in length and each one is baited with a sardine. You’re supposed to set the line at night, and our boat did. If you set the lines in the day it catches the attention of albatrosses. They can’t resist all those sardines. And if an albatross catches one as the line is going into the water, it’ll drown. One of the fishermen on our boat had previously worked on an illegal boat, poaching down in the Southern Ocean, and he described how they’d caught 400 seabirds in one single go. Now, not all of those were albatross. But it’s still pretty dreadful. By contrast, in the couple of months we were fishing, we caught only four, and two of those were still alive. We managed to save them because they were snagged as we were retrieving the line.

Describe the storm that eventually sank the boat.

On the sixth of June, we woke up to the roughest conditions we’d faced. My favorite way of describing it is at ten o’clock in the morning, when I was out on deck, the waves were actually casting shadows. If you work out how high the waves have to be to cast a shadow at ten o’clock in the morning, it was ridiculous. But we were still fishing. I was struggling to stay upright on deck. I had my legs braced against the railings, but just staying on your feet was a big problem.

By the time we were rescued, I was close to death. I was deeply hypothermic, and barely able to function.

Were you aware that the ship was in trouble?

The moment I knew we were in real trouble was when Danie, one of the crew, asked me for a knife. When we refuelled, Danie had said to me, “Look, if we ever have to get off this boat, abandon ship, then the crew will fight with knives for a space on the raft.” I would expect everybody would help each other. But I took heed of Danie’s warnings, because he was someone that looked after me on the boat. On the afternoon of the storm, he said, “Matt, can I borrow one of your knives?” I passed him a big filleting knife. He took it, stabbed it in the chopping board and said, “ Now it’s ready.” I thought, oh crikey, that means we’re about to abandon ship. It was one of the clearest signals that we were in real trouble.

Ten out of seventeen people died in your life raft. Without giving too much away, describe your ordeal.

When we abandoned the Sudur Havid I didn’t know whether a May Day had been sent or if there were any boats nearby. The nearest boat I knew of was 100 miles away. We drifted away from the Sudur Havid in three life rafts. In my life raft there were seventeen of us, so it was heavily laden. The big steel arch on the back of the fishing boat came crashing down so we were flooded with seawater that was minus one degrees. We were waist-deep and adrift in a damaged life raft, in the middle of the Southern Ocean, 170 miles from land. We tried to bail the raft, but more waves kept coming in. So, in the end, we had to just seal down the hatch and wait. Though we didn’t know what we were waiting for.

What did your crewmates die of?

The coroner’s inquest said hypothermia, but I think most of the guys either drowned in the water in the life raft or were killed by cold-water shock. If you can imagine this, our canteen steward was in flip-flops and a t shirt when we abandoned. He’s come from Namibia to a galley on our boat and into water at minus one. I doubt he could even swim, so he really didn’t stand a chance. There were no survival suits on board, none of the modern safety equipment that we should have had.

Why do you think you survived?

By the time we were rescued, I was close to death. I was deeply hypothermic, and barely able to function. I was wearing a deck suit that wasn’t sealed. It didn’t keep me dry but it kept me a bit warmer. I knew from scuba diving training that I was better off out of the water than in it, so I tried to keep myself up out of the water and busy with small tasks, whether bailing the life raft or tying down the flaps or adjusting my suit.

I blamed the owner because he put us at sea in a vessel that wasn’t ready for it.

What were your emotions when you were rescued?

You probably want to hear it was overwhelming joy, but by the time we were rescued, my brain felt so slow I just felt relief. You try to keep up your hope that you will be rescued, but how long can you keep up hope when you know that it’s nighttime and the storm is raging? I didn’t think we were going to die, which is strange. But I didn’t see how we were going to be rescued. When I fell on my face on the deck after being rescued I just remember feeling relief more than anything—and the blessing of slowly getting warm again.

The South African inquiry squarely pointed the finger at the officers commanding the ship as the culprits. Do you agree?

I didn’t at first. I blamed the owner because he put us at sea in a vessel that wasn’t ready for it. But if “Bubbles” McDonagh [the captain] and Boetie [the fishing master] had listened to us when we were warning them we had problems, they could have saved the boat. We would have lost some fish and maybe some equipment, but we’d still have had the boat and everybody on it. They lost 17 lives for a few hours fishing.

The book ends with the birth of your daughter. You gave her a name with special significance, didn’t you?

She’s called Camilla, after the boat that saved us, the Isla Camilla, from Chile. It’s hard to believe how lucky we were to be found so quickly. If you think about the trouble that the Coast Guard has finding lost mariners, we were found within about half an hour of the Isla Camilla arriving on the scene—at night, in an unlit raft. I don’t think you get any luckier than that. Later, I met one of the deck hands, who pulled me on to the Isla Camilla, in a pub and promised him if I had a daughter her name would be Camilla. I eventually also made contact with Captain Sandoval who saved us, and told him I’d named my daughter after his boat. So I got to fulfil that promise. That was beautiful.

Simon Worrall curates Book Talk. Follow him on Twitter or at simonworrallauthor.com.