No one knows what sank the Edmund Fitzgerald. But there are clues.

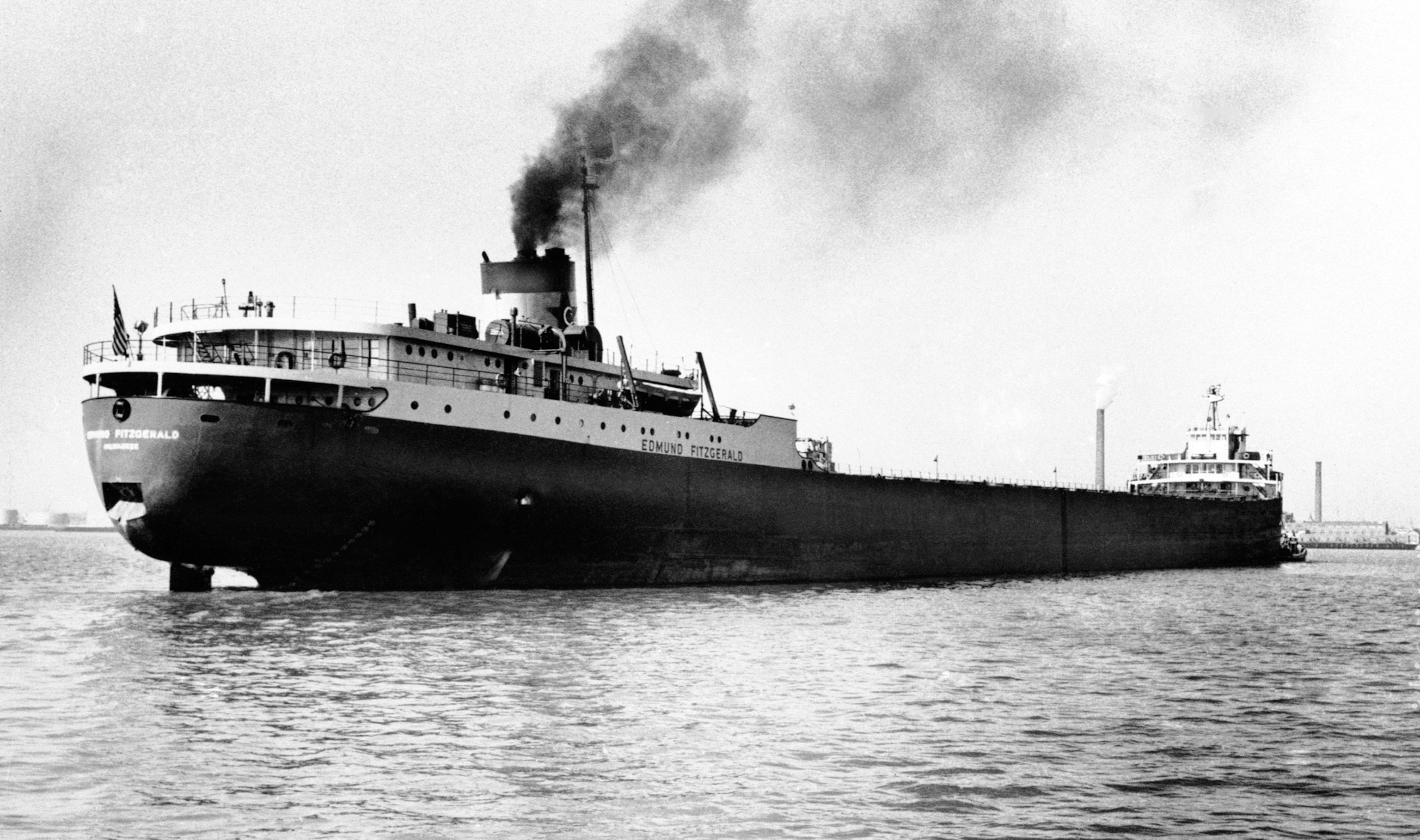

The Great Lakes freighter was one of the most technologically advanced of its time when it wrecked in Lake Superior 50 years ago. What went wrong?

The good ship and crew were in peril. A savage storm was hurling hurricane-force winds, 35-foot waves, and blinding blasts of snow at the large freighter. Already reporting a “bad list” with no radar and damaged ballast vents, it was taking on water and making slow progress battling its way across Lake Superior on November 10, 1975.

Still, the vessel’s skipper, Ernest M. McSorley—considered one of the best on the Great Lakes—was not overly concerned. “We are holding our own,” he said over the radio to another ship’s captain about 10 miles away. One of the most technologically advanced freshwater freighters of its time, McSorley likely believed his ship could still make it to safe harbor.

Moments later, though, all communications ceased and the S.S. Edmund Fitzgerald vanished from radar screens. It was another tragic loss on the Great Lakes, which has claimed an estimated 6,000 ships and 30,000 lives since 1875.

Fifty years ago, “The Fitz” sailed into history when it suddenly sank in 530 feet of frigid water on the Canadian side of Lake Superior with the loss of all 29 crew, including McSorley. There had been other maritime disasters with more deaths on the Great Lakes, but none received the notoriety of this sinking: In 1976, after reading a Newsweek article, Canadian singer-songwriter Gordon Lightfoot immortalized that tragedy with his poignant rock ballad “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald”—which gets most of the known facts right.

(How one catastrophic shipwreck sank a medieval dynasty.)

“The ship was indeed the pride of the American side,” says Bruce Lynn, executive director of the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum, located at Whitefish Point in Michigan, about 17 miles from where the Edmund Fitzgerald went down. “The crew was proud to serve on the freighter, which held the record for shipping weight until the thousand-foot ships came along.”

But the song doesn’t tell the full story of the tragedy. What exactly happened on that fateful day remains a mystery. John U. Bacon, author of recently published The Gales of November: The Untold Story of the Edmund Fitzgerald, believes it was likely a combination of failures that led to the sinking.

“It was a series of unintended consequences,” he says. Sorting through the facts offers an intriguing look at a disaster in the making.

Sailing into history

In the early afternoon of November 9, 1975, The Fitz departed Superior, Wisconsin, on its way to a steel mill in Detroit. At 729 feet long, it was one of the largest freshwater freighters at that time and included first-rate accommodations. The ship was named for Edmund Fitzgerald, president of Northwestern Mutual Life Insurance, which owned it.

It was loaded with 26,000 long tons—about 29,000 short tons—of taconite pellets, made from low-grade iron ore, powdered and bound with clay. The weather was spectacular that day: temperatures in the 70s with fair winds and light seas, though a storm warning had been issued.

The National Weather Service had tracked an approaching Alberta Clipper, a fast-moving low-pressure system carrying dry, cold air from the northwest. Almost unseen was a second storm from the southwest, bringing with it warm air and moisture.

When the two systems collided over the Great Lakes the next day, it created an epic tempest—Lightfoot poetically called it a “hurricane west wind”—that slammed ships with violent gusts, whiteout snow, and massive waves.

(The 'least spectacular' of the Great Lakes is a devastating snow machine.)

As the weather turned bad, McSorley opted to travel the northern shipping route close to Canadian shores for protection from the wind. When he turned south for Detroit, the Edmund Fitzgerald faced a broadside of 70-mile-per-hour winds and waves some 25 feet high for several hours.

That was a problem for the freighter, which had a Plimsoll line only 11.5 feet below the deck. That mark on a ship’s hull indicates the maximum depth to which a freighter can be loaded with cargo—if the waterline rises above the Plimsoll line, it means the ship is overloaded. With that little distance from the waterline to the deck, wind-driven waves could easily roll over the ship. Damaged or missing ballast vents, which were reported by the captain, would have also allowed water to flood below, causing the vessel to sink deeper.

In addition, rogue waves as high as 35 feet may have struck the ship. Jesse B. “Bernie” Cooper, captain of the S.S. Arthur M. Anderson, which trailed the Edmund Fitzgerald, reported being hit by three massive waves in succession just before losing contact with the ill-fated freighter.

“The absolute energy of a Great Lakes storm is amazing,” Lynn says. “When dramatic weather closes in, conditions deteriorate quickly. Because fresh water is less dense than salt water, waves on the Great Lakes have a different action. They tend to be sharper and more frequent than ocean swells. They also freeze faster, causing the ship to become top heavy with ice.”

(The Endurance disappeared over a century ago. Here's how explorers found the famous ship.)

The ship was sailing blind after losing both short and long radar systems, probably due to wind and wave action. It stayed in touch with the Anderson, however, which monitored The Fitz’s progress toward Whitefish Bay, a protected inlet. At one point, Captain Cooper became alarmed when his radar showed the ship sailing over Six Fathom Shoal, a dangerous rock outcropping on the Canadian side of Lake Superior.

Shortly after that, the ship disappeared and sank beneath the angry waves of Lake Superior.

“Whatever happened happened fast,” Bacon says. “There was no SOS. No time for lifeboats or lifejackets. The crew was trapped inside the ship. Families can take solace knowing there was no prolonged suffering.”

Investigating the clues

One theory for what really happened that day is that perhaps it was a failure of the ship’s construction.

When The Fitz was built in 1954, it was considered to be technologically superior to the rest of the Great Lakes fleet. Instead of being fastened with rivets and bolts, which was standard, the large freighter featured steel plates welded to its hull, which were supposed to make it flexible enough to bend and give in the tempest-tossed Great Lakes.

However, constant pummeling in a fierce storm like the one that struck Lake Superior 50 years ago might have weakened those welds to the breaking point. This theory holds that the seams buckled when the bow and stern were riding giant waves but the heavy center section was unsupported over a trough.

“It’s like a paperclip,” Bacon says. “You can only bend it so many times before it gives.”

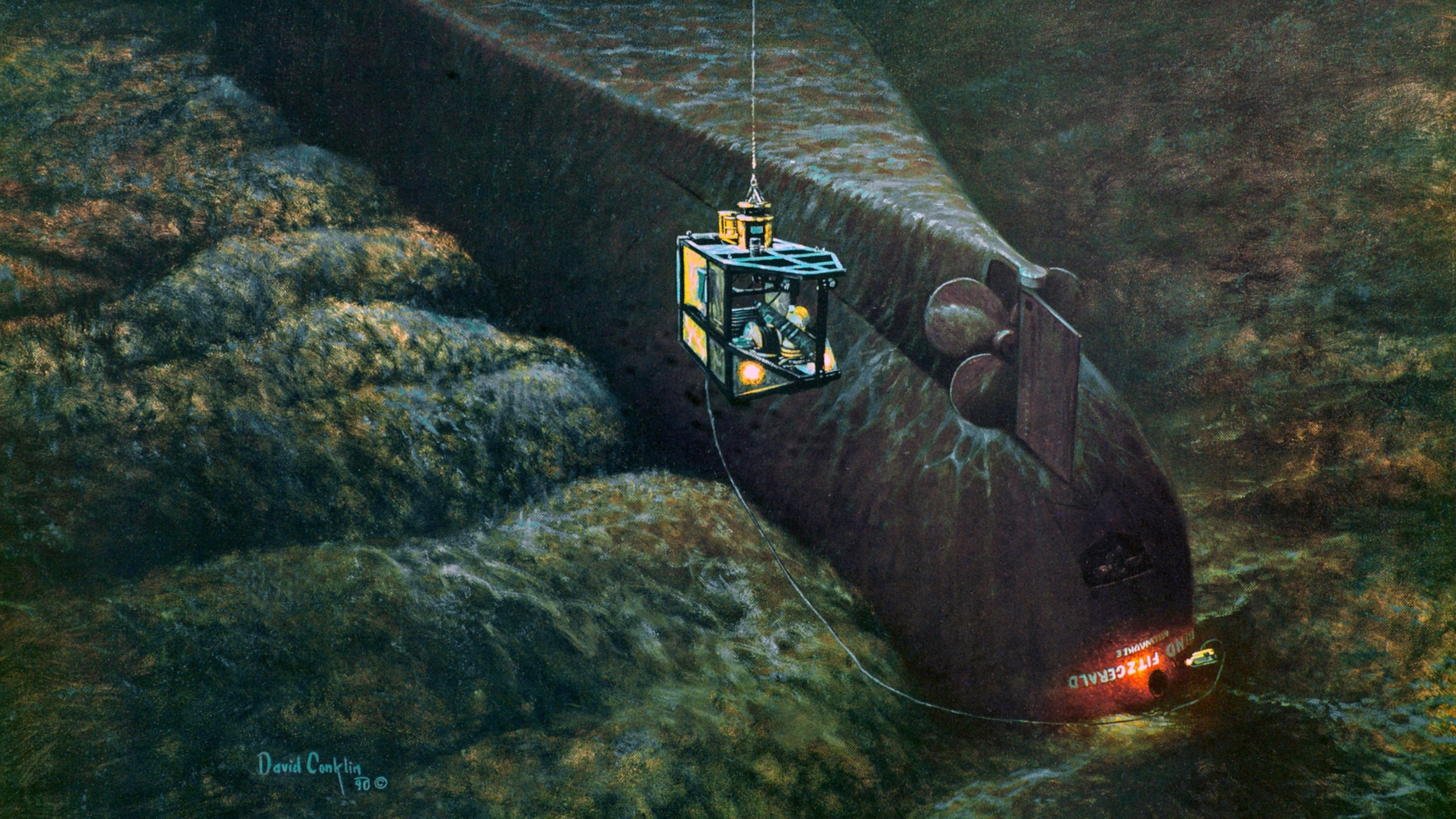

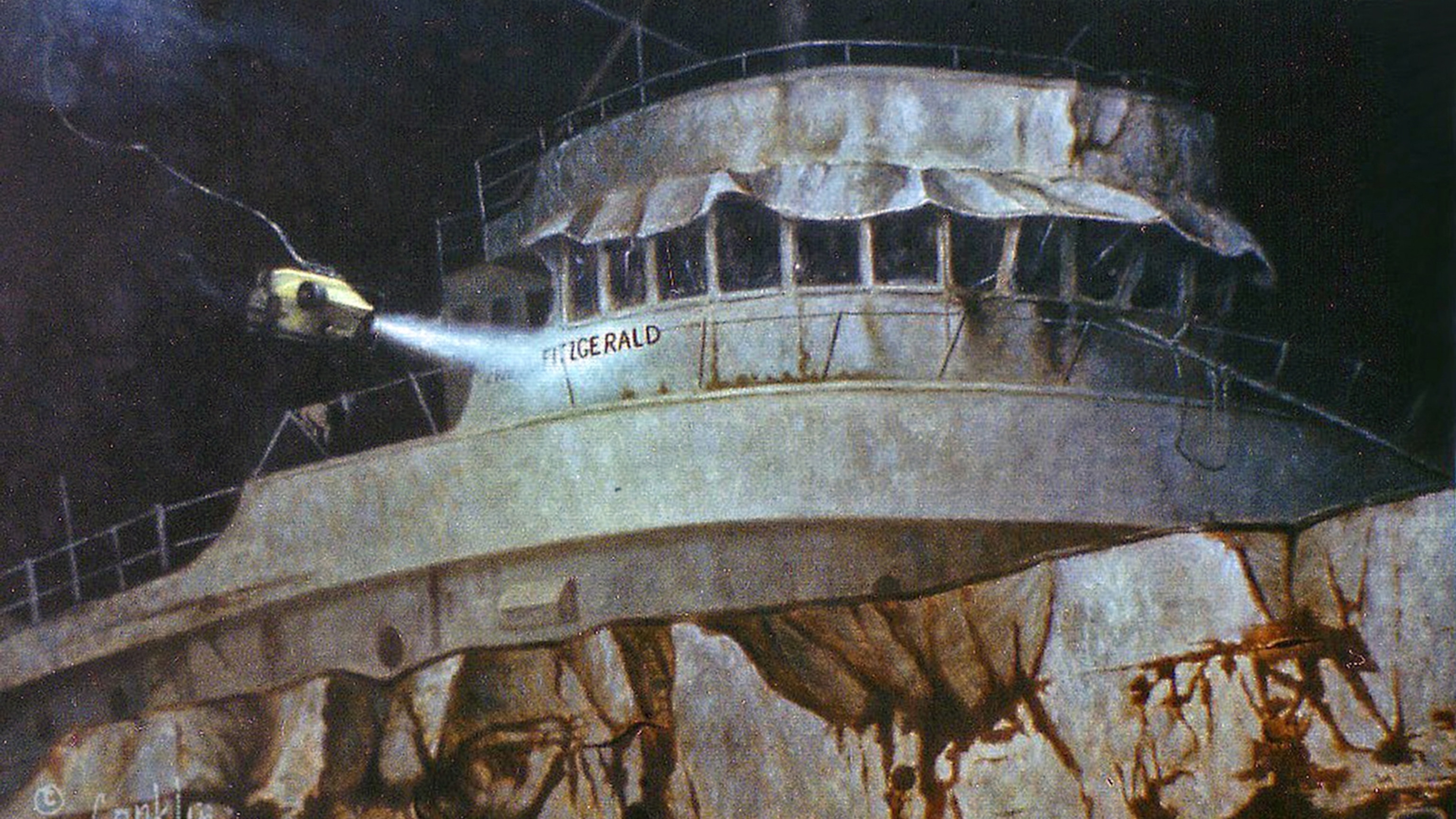

The Edmund Fitzgerald was found in two pieces, giving rise to speculation that the ship broke in half during the storm. Yet it is unclear if the break occurred on the surface or when the wreck struck bottom.

(We may finally solve the mystery of the shipwreck that lies beneath Ground Zero.)

Then there’s the report of the ship sailing over the dangerous Six Fathom Shoal. One investigator later claimed he discovered maroon paint from the Edmund Fitzgerald on the shoal. However, the confidential report he produced for Oglebay Norton, the company that operated the ship, was never released. If true, water rushing in from a hull breach could have caused the “bad list” reported by The Fitz’s captain.

The U.S. Coast Guard also launched an extensive investigation into what might have happened. The resulting 100-page 1978 report ultimately blamed “ineffective hatch closures” as the likely cause, though subsequent marine explorations showed no evidence of that.

According to Bacon, the cause of the sinking was likely a combination of factors resulting in a catastrophic failure. “I don’t think it was any one thing,” Bacon says. “A series of mishaps and miscalculations contributed to the disaster.”

The legend lives on

The sinking of the Edmund Fitzgerald had a devastating impact on the families and friends of those who were lost. This tight-knit community where everyone knows each other left a mark that is still felt to this day.

The loss of the big ship also resulted in rule changes for freshwater freighters. Some of it was technical to make commercial vessels more reliable, Lynn notes, such as improved navigational charts and weather forecasting, as well as electronic positioning beacons to identify location (later replaced by GPS).

“The sinking actually made shipping safer,” he says. “Now, when the weather turns bad, freighters must drop anchor and wait out the storm. The men on the Edmund Fitzgerald did not die in vain.”

Since 1975, no commercial ships have been sunk or lost lives on the Great Lakes.

On July 4, 1995, the ship’s bell was recovered from the wreck. It is now on display at the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum, where it is rung on the anniversary of the sinking—“29 times for each man on the Edmund Fitzgerald,” according to the song.

What exactly happened on that dark, cold night 50 years ago will probably never be known.

Perhaps Ruth Hudson, mother of Bruce, a 22-year-old-deckhand and a father-to-be when he perished on the fated freighter, said it best. In his book, Bacon quotes her as saying: “Only 30 know what happened: 29 men and God.”