This Ancient British Monument Was 10 Times Bigger Than Stonehenge

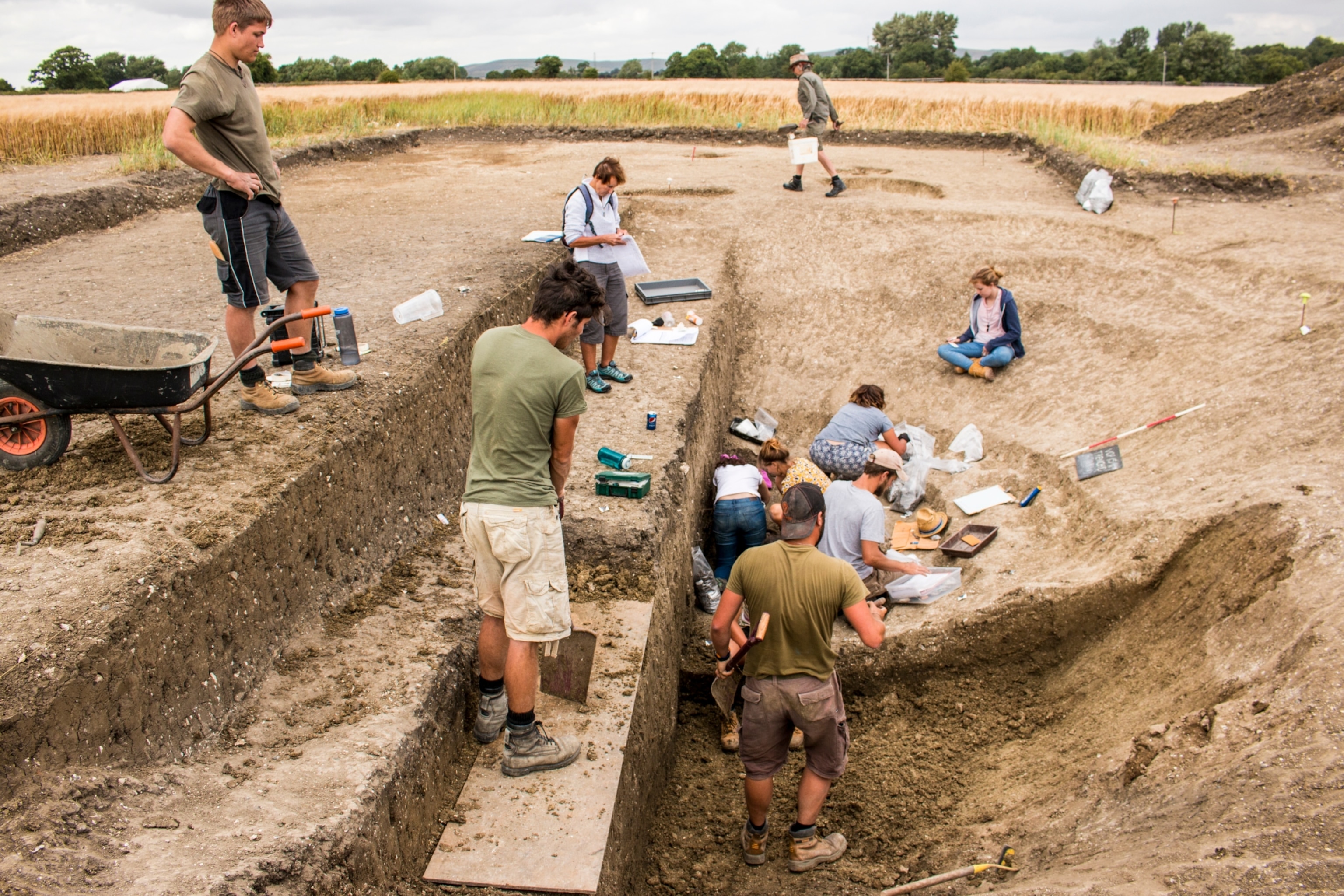

As they excavate the site, archaeologists search for clues about what caused an “insane” building boom in Stone Age Britain.

PEWSEY VALE, England —

The sheer size of Marden Henge makes it hard to notice from the ground, even when you’re standing in the middle of it.

Its massive earthen berms, once ten feet high and encircling nearly 40 acres, have gradually slumped over the millennia. Its fertile soil has been heavily plowed by farmers, grazed by cattle and sheep, and overrun in places by sedge, nettle, and stately oaks. When you look around the henge today on a fine summer day, it appears to be nothing more than peaceful, undulating farmland.

But 4,500 years ago this was a bustling showpiece of Neolithic engineering, the biggest henge (or circular earthworks) in ancient Britain—ten times the size of Stonehenge, a few miles to the south.

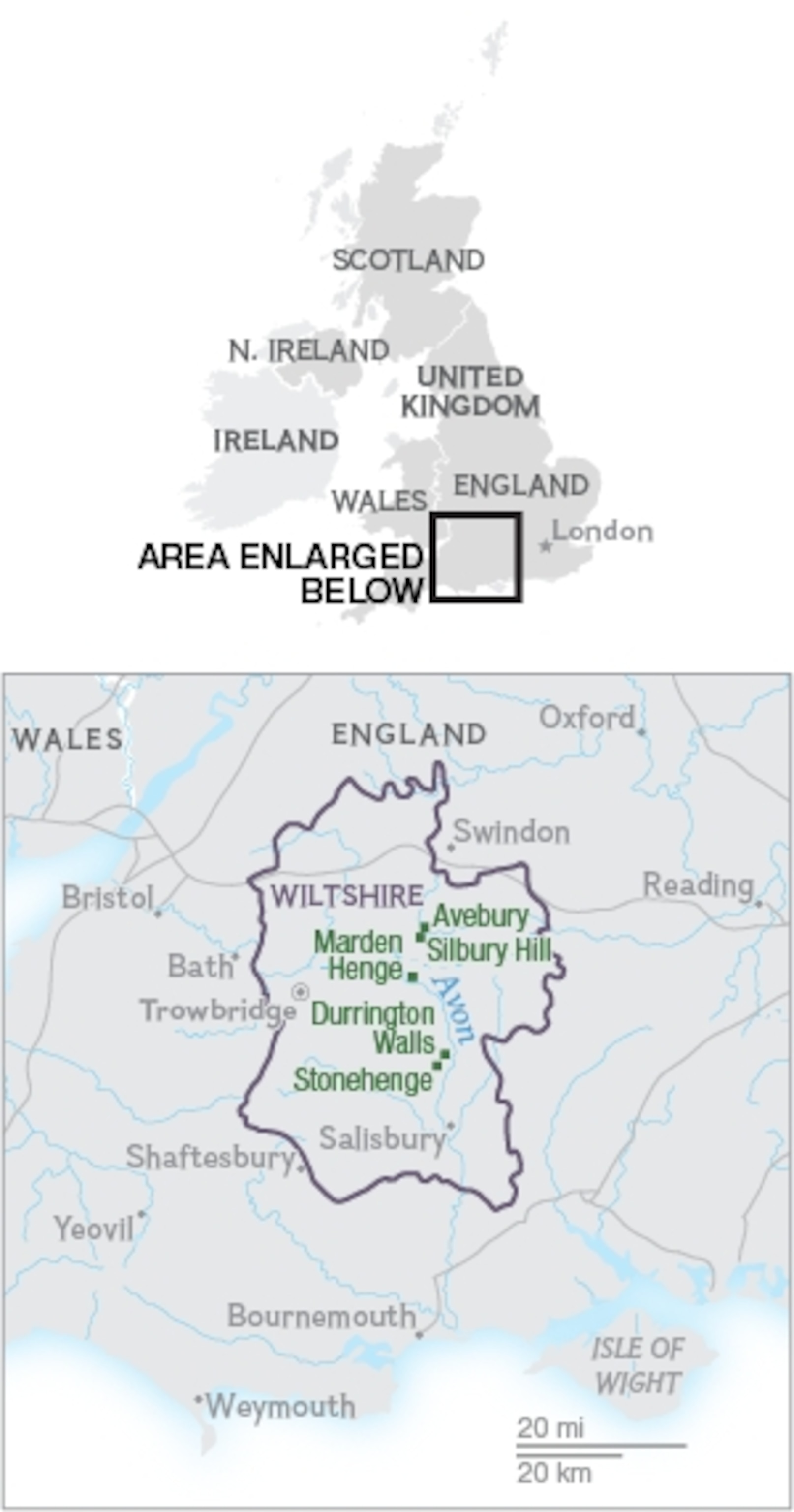

No one knows why Marden Henge was built, or what caused the frenzied construction boom that produced it and other Neolithic monuments—including Stonehenge, Avebury, Durrington Walls, and Silsbury Hill—located within a few miles of each other along the River Avon. It’s an ancient riddle that Jim Leary, director of the archaeology field school at the University of Reading, hopes to help solve.

Last month Leary, in partnership with Historic England, launched a three-year excavation of Marden Henge. Despite its massive size, the site has attracted little attention from archaeologists, who have tended to focus on the more visually gripping monuments.

“Not nearly enough attention has been paid to the archaeology of the fertile valley in between these places,” says Leary, whose excavations this summer and in 2010 have been the only ones at Marden since the late 1960s.

Stone Age Bling

Already the site has been repaying Leary’s efforts with the discovery of an early Bronze Age burial and a trove of artifacts from a rare, well-preserved stone building in the heart of the henge. The artifacts include beautifully crafted arrowheads that seem to have been made purely for show—Neolithic bling.

The skeleton, apparently that of a young teenager about 5 feet tall, was unearthed just outside the main embankment of Marden Henge, in a smaller enclosure known as Wilsford Henge. He or she—the sex is undetermined as yet—was buried with an amber necklace about 4,000 years ago, a time that post-dates by a few centuries the glory days of Marden Henge.

“What this burial highlights is how important these Neolithic monuments continued to be in the Bronze Age,” says Leary. “Presumably they retained a certain sanctity as an appropriate place to bury the dead.”

The stone building was constructed of chalk blocks quarried several miles away and dragged to the site. It seems to have been the scene of feasting on a lavish scale, judging by the prodigious amount of pig bones found beside it.

“We’ve found the remains of at least 13 pigs so far,” says Leary, “and that’s just in one small area. We are talking about a lot of meat here. This would have been a big deal.”

Smokehouse or Sweat Lodge?

A layer of ash near the center of the building indicates a very hot fire was kept burning here for long periods of time. It may have been for roasting the many pigs, or possibly for firing bluish sarsen stones that were found nearby and whose minerals show signs of having been repeatedly heated white-hot.

“This was no mean fire they had,” says Elspeth St. John-Brooks, a Ph.D. student in geoarchaeology at the University of Reading. She is doing geochemical analysis of trace elements and isotopes found in the earthen floor to try to determine its use. “It scorched the ground beneath it to a depth of several inches. It would have been very hot inside there.”

One interpretation is that the building may have served as a kind of sweat lodge where initiates or celebrants were cleansed before participating in ceremonies. Another, more prosaic, explanation is that it could have been a smokehouse where hog roasts were prepared for feasting.

St. John-Brooks is intrigued by a third possibility: With the dawn of the Bronze Age just over the horizon, this may be where people of the late Neolithic era made the first tentative attempts to smelt metal.

“It would be huge if that were the case,” she says. “And it’s something we should be able to establish. If that’s what they were doing here, the markers should be pretty obvious in the soil.”

Building Boom “Utterly Unsustainable”

Certainly something big was going on in this part of Britain during the late Neolithic era to have prompted the rash of monument-building and outpouring of wealth.

“It was insane, utterly unsustainable,” says Leary. “We tend to think of people during the Neolithic as somehow being at one with their environment, but they appear to have been just as bad as we are. They were clearing, felling, digging, and consuming their environment at an unsustainable rate in building these huge projects.”

Religious fervor may have played a role, says Leary, or perhaps a desire by increasingly hierarchical communities—or their leaders—to flaunt their wealth and ability to mobilize a huge workforce.

How many man-hours it would have taken to build Marden Henge, digging with picks made of bone and antler and using woven baskets to carry away the soil, is anyone’s guess. But the figure would be huge—and a clear indication of the site’s importance.

“For all the attention that has been lavished on Stonehenge over the years,” says Leary, “we may well find out that Marden was where it was really at during the Neolithic.”