The Maya civilization was a mystery. Our family business was solving it.

As the son of archaeologists, National Geographic Explorer David Stuart spent his childhood wandering ancient Maya ruins—and helped shape what we know about the civilization today.

My earliest memory is of a faraway Maya pyramid. A lofty, stony thing in the Guatemalan jungle, with steps leading to a doorway—impossibly enticing to my three-year-old self looking upward, determined to scramble up to the top. But my mom would have none of it.

She and my father were both archaeologists and worked at National Geographic in the late 1960s and ‘70s, where they took me and my siblings on expeditions to Maya ruins, encountering places and peoples that no American kid at the time could ever imagine.

The resulting tantrum I threw over not getting to climb the stone steps at Tikal—now known as one of the most significant centers of early Maya civilization—is an early memory too. Did I care what that ancient pyramid was for, or who built it? Of course not. But these memories were among my first encounters with the world of the ancient Maya, a world that shaped my childhood. I gradually was to become enchanted by the worlds of the ancient Maya and make such questions central to my research.

In those early days no one could say much at all about Maya history. Even the name of the king who commissioned the pyramid at Tikal, and whose rich tomb was found buried within, remained a mystery to archaeologists. The reason for our ignorance was simple—Maya hieroglyphs could not yet be read, leaving centuries of history from the Maya “Classic period” (roughly C.E. 200 to 900) invisible and inaccessible, locked away in the hundreds of stone inscriptions at Tikal and many other sites. This is what I think of as the “Great Rupture” in historical knowledge. The real story of Maya civilization had long been lost due to societal collapse and, later on, the cultural destruction that came with the Spanish invasion.

(Everything we thought we knew about the ancient Maya is being upended.)

Today, thanks to new breakthroughs in reading the ancient texts, we can revisit that history and bridge the rupture. As it turns out, the great pyramid at Tikal was built by a powerful ruler named Jasaw Chank’awil, to commemorate his great military victory of his enemy, the Kanul kingdom, in C.E. 695. His story and many others are recounted in my new book, The Four Heavens, which aims to bring the history of the “mysterious Maya” into our own historical consciousness.

Learning to decipher the glyphs

Our two-week drive from North Carolina to Yucatán, Mexico, ended on a dark night in 1974 in a remote place called Coba, where my father was to start his new research project, mapping, what they excitedly said, was a vast ancient city. We arrived at the Maya village in complete darkness, no electric light anywhere to be seen except for a flashlight in the distance. As we rattled our way down the dirt road, I vividly recall looking out the window of our truck, seeing a massive pyramid silhouetted against a night sky that was gray, so dense with stars. I was then nine years old, nervous at what lay ahead but anxious to see the pyramid in the daylight, and to climb it.

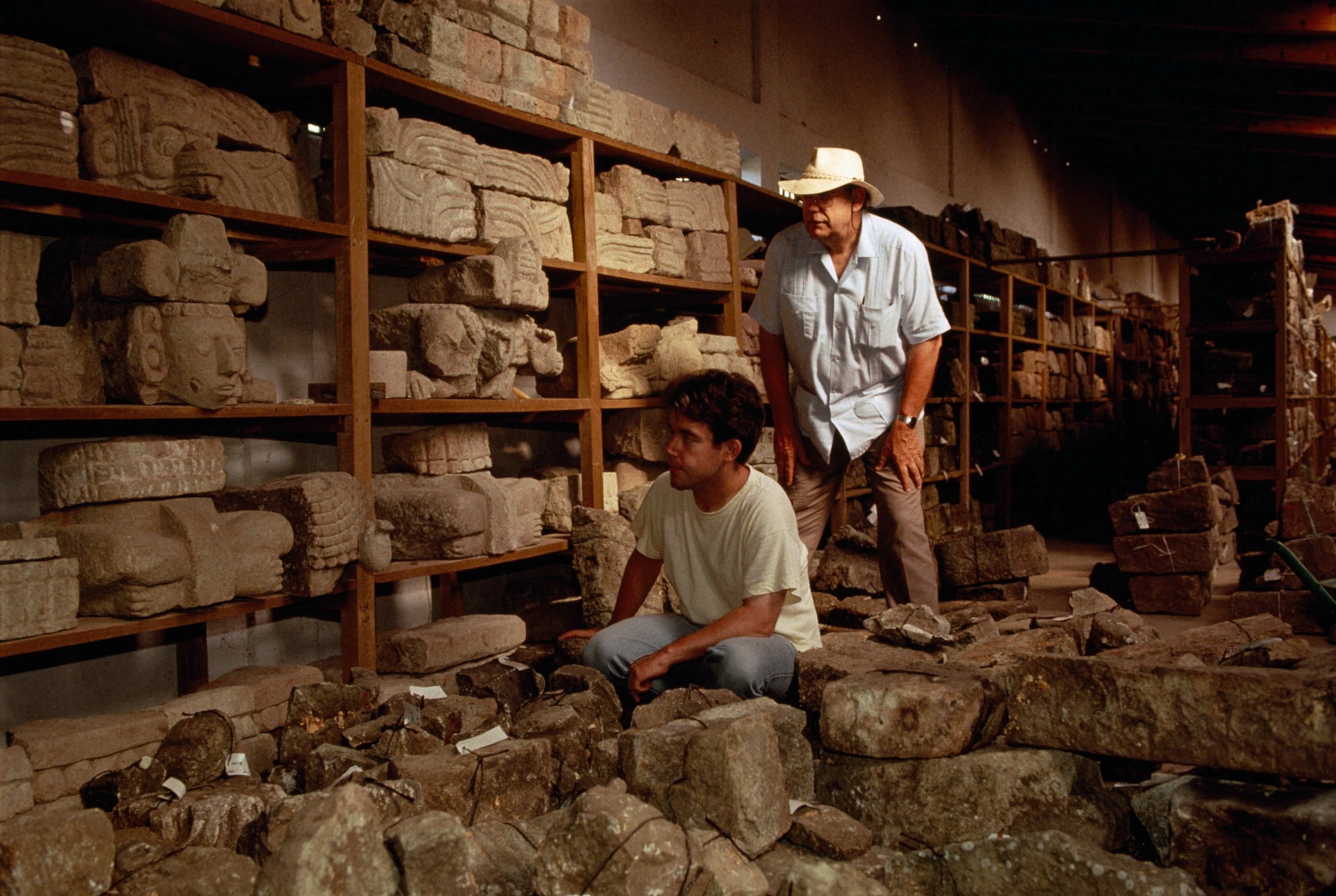

My parents’ workplace was a constant influence in my young years. My father, George Stuart, was a writer and editor for National Geographic magazine, and later head of the grant-making wing of the Society—the Committee for Research and Exploration. My mother, Gene Stuart, was an artist and a writer at the magazine too. I was enamored by the adventure of archaeology, and soon by the constant discoveries being made. What else could I ever want to do but become a Maya archaeologist?

But a key element in understanding the ancient Maya was still missing back in the mid-1970s—the ability to read the ancient texts, and to make sense of the mysterious hieroglyphs. As a kid, wandering the ruins of Coba, I recall seeing the strange forms of the writing on stone monuments, still standing in the forest. “What do these say?,” I asked my dad, pointing to the glyphs. “We still can’t read them,” he would tell me.

(The hidden ruins of the great Maya Snake Kingdom were almost lost to time.)

From then on I was hooked. The glyphs were so interesting to look at, with their images of animals, heads, and weird shapes. I read (or tried to read) what little illustrious scholars could say about them. Most Maya archaeologists were my dad’s friends, and so, at parties or chance meetings, I would often ask them the same questions too. Over time the interactions and conversation grew deeper, and by the time I was in my teens, I was making my own small contributions to solving the puzzle. Fifty years ago, Maya studies was a remarkably open field, part academic, part experimental, eager to hear new voices and ideas. I timed my entry well.

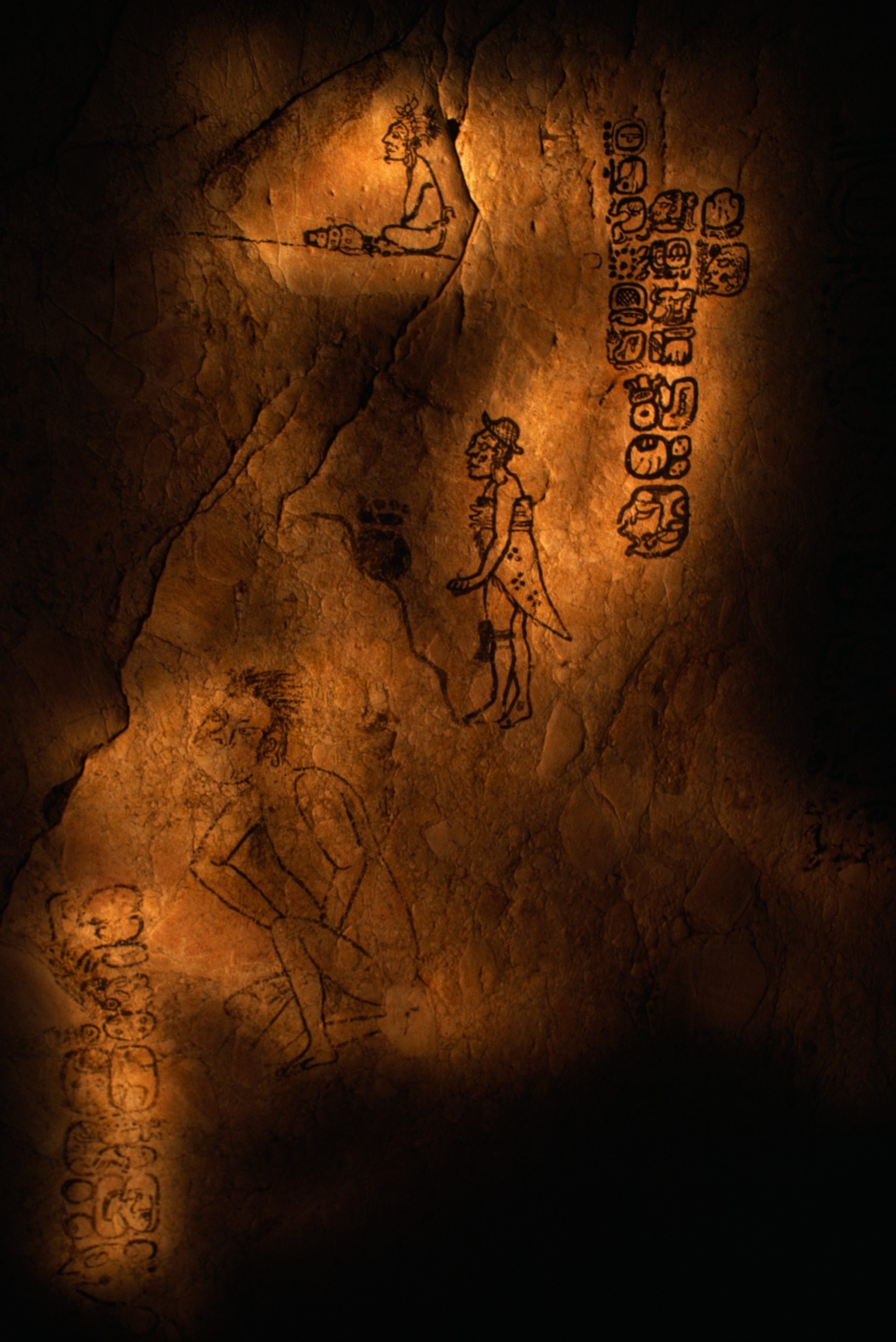

In the fall of 1980 my father received word of a newly discovered cave in Guatemala, full of ancient drawings and elaborately painted hieroglyphs. Wilbur Garrett, the editor of National Geographic magazine, and my father immediately organized a trip to see the cave firsthand in an expedition that ended up being the subject of the August 1981 issue. I was brought along to study the glyphs—both for my own enrichment and because I had by then shown an aptitude for it. (Being in ninth grade, however, I needed permission from Bethesda Chevy-Chase High School to be away from classes and get my homework in order.)

The cave, we learned, was called Naj Tunich. We arrived after a long hike through the woods, near the Belize border, and were greeted with a cathedral-like opening in a hillside. To get to the paintings, we had to make our way hundreds of meters into the deep recesses of the cave, through large tunnels and small passageways. Ceramics of the ancient Maya were lying everywhere, attesting to its long use as a sacred site. Inside the cave we encountered beautifully inscribed texts on the smooth walls, painted by master calligraphers. Mentions of dates, names, places were everywhere. There and then I made my first decipherment, realizing a scribe in the eighth century used phonetic signs to spell the name of a month of the Maya calendar. Later, I and others would realize the paintings of Naj Tunich were done by royal pilgrims visiting a sacred site, an entrance into the underworld.

Filling in the gaps

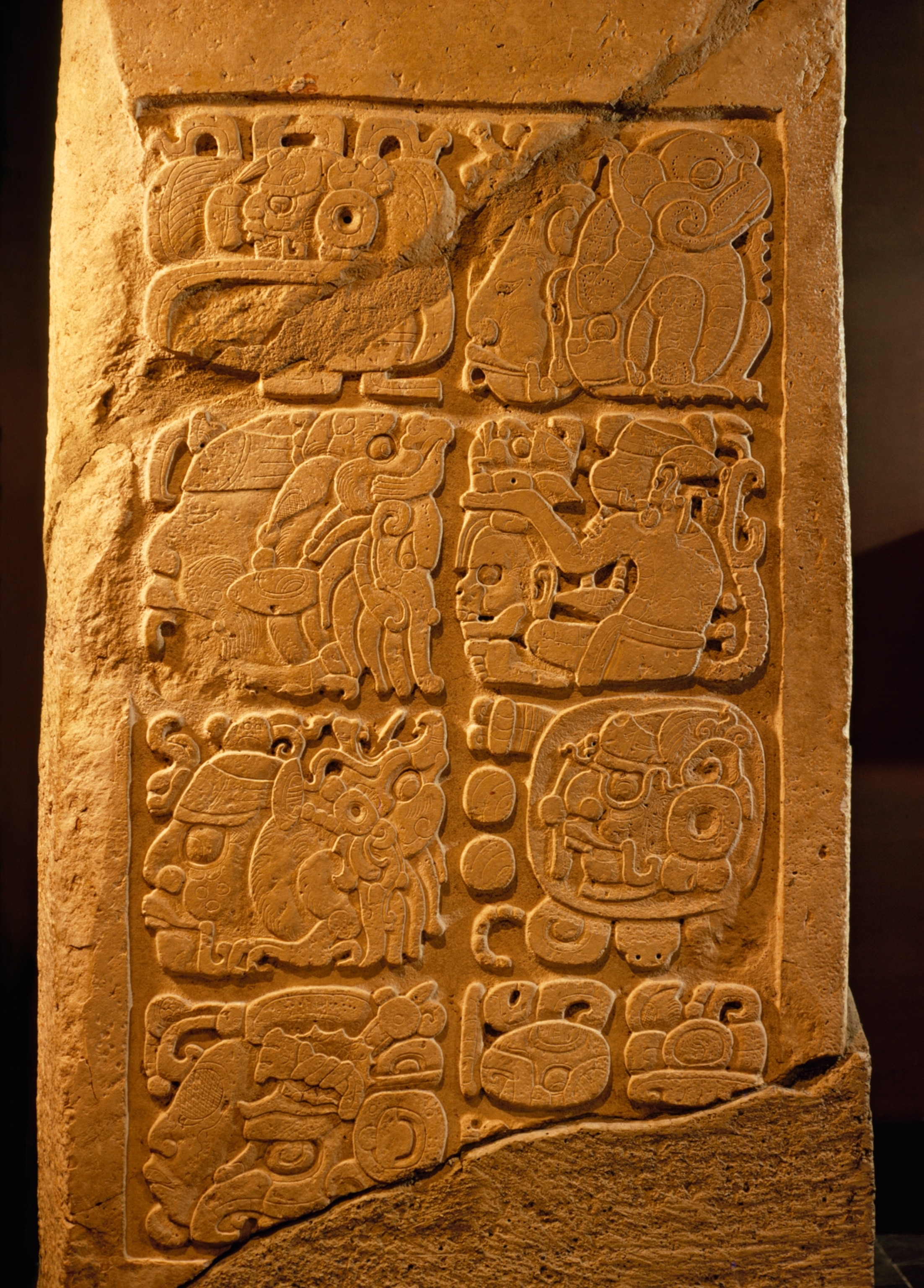

One expedition I joined in 1985 at age 19 was especially memorable—filled with discovery and even a true Indiana Jones moment mixing archaeology, ancient history, and a bit of high adventure. This was a trip down the Usumacinta River, on the border between Mexico and Guatemala, still very wild in those years and under threat from hydroelectric dams and the civil war in Guatemala as National Geographic would document in the October 1985 issue. The expedition team rafted for days through the forested terrain and rocky canyons, spending a few days at the beautiful ruins of Yaxchilan, Mexico, with its gorgeous sculptures and temples looking down upon the river below.

Recent excavations had revealed a new stone inscription (one of many) that I was anxious to see. No one had been able to read it after its discovery, but I looked upon it in amazement, as it was a written list of the first kings of the city’s ancient dynasty—four names of rulers who probably lived in the fourth and fifth centuries C.E. One name read Yopat Bahlam, and another was Yaxun Bahlam. Maya history was laid out before me, and I was the first person to ever read these names in perhaps a dozen centuries.

Two days later, our expedition camped on a quiet sandbar along the river, in Guatemalan territory, still far from any settlements. We were soon greeted by a band of Guatemalan rebels with automatic rifles drawn, their faces covered in bandanas. We seemed a suspicious bunch, no doubt, but we eventually convinced them we were focused only on the ancient ruins. They excitedly told us of sites they knew in the forest, which no one had yet explored. We didn’t dare go after them, however, and risk becoming targets in the active military conflict.

Throughout the ‘80s, a new wave of scholars was making rapid headway in Maya decipherment, and by the end of the 1990s the hieroglyphs were almost completely readable, thanks to the work of a dozen or so persistent scholars, myself among them. Looking back, something amazing had happened—the older history of the ancient Maya had emerged from complete obscurity. Many dynasties and kingdoms, each with its own story to tell. This was a completely new history, filling in a gap that we didn’t even know existed. Most of what we knew about Mesoamerica came from when the Spanish arrived on the shores of Mesoamerica in the early 16th century. Or it came from the Indigenous chronicles that the Maya and others kept here and there. None of those histories went back more than a few centuries, however, to the time before the era of the so-called “Maya Collapse,” the still mysterious crisis when most courts and cities were abandoned, before about C.E. 900.

The new history we are now able to read presents a world of kings, queens and royal courts, and of lost stories that came before the Collapse and the historical rupture I have described. Today, because the ancient Maya wrote down so much about themselves, we can at last bridge the gap, and recover something once almost completely lost to human history. My new book is my attempt to weave many of those narratives together, and to tell the intellectual story of how we got here.

My early memories of Tikal and Coba, with their immense pyramids, are from a time when none of that was knowable. Decades later, we all can appreciate ancient Maya monuments much like those we’ve long known Egypt or Greece, with true historical setting. What is most important, I think, is that we now have access to the deepest history of the Americas, and that the modern Maya can claim it as their own ancestral legacy.