Archaeologist's Execution Highlights Risks to History's Guardians

A scholar's brutal death at the hands of ISIS is a reminder that archaeologists can find themselves on war's front lines, protecting artifacts.

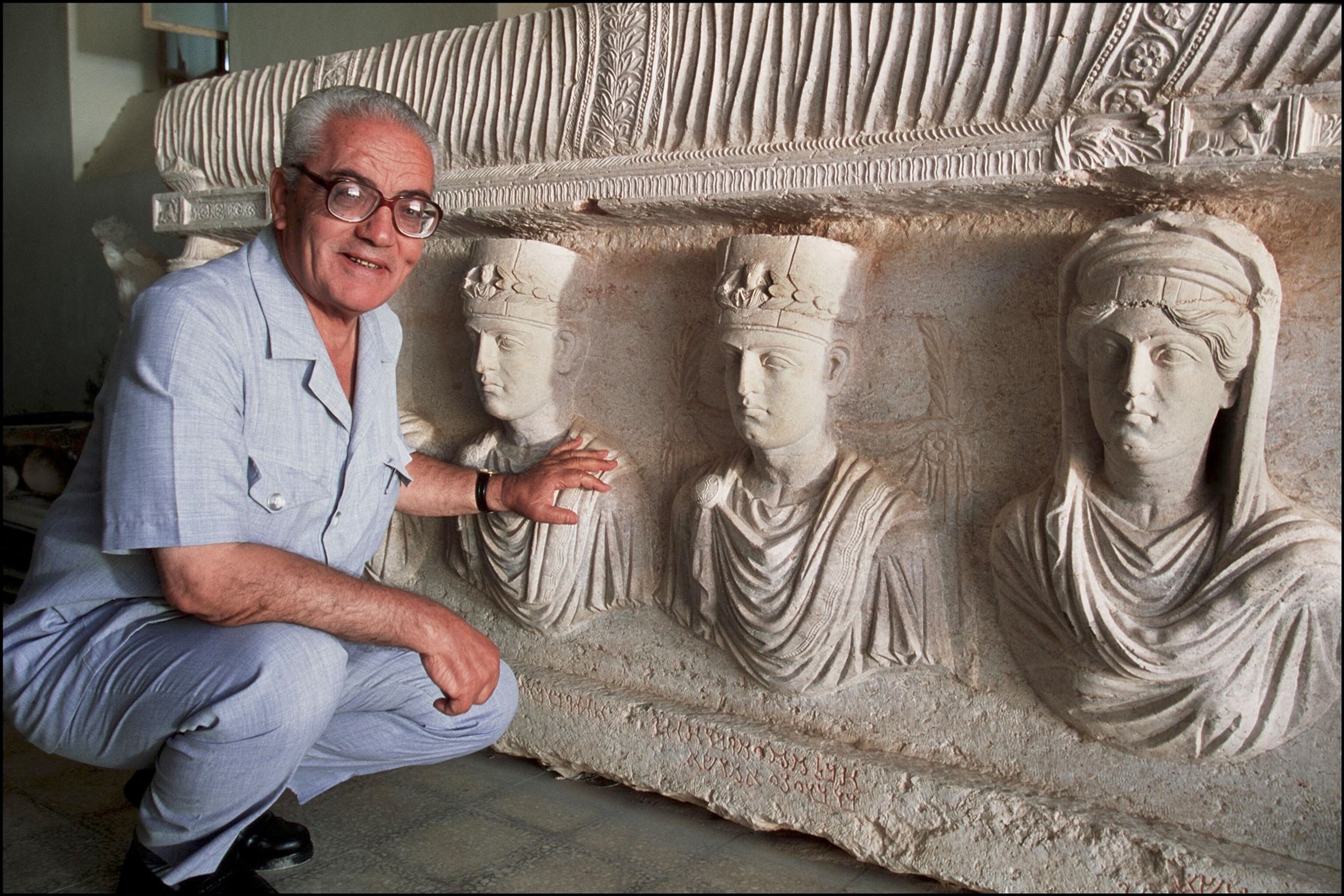

Khaled Asaad dedicated his life to excavating and restoring the 2,000-year-old ruins in the Syrian city of Palmyra.

That dedication led to his death.

The 82-year-old scholar, who worked for more than 50 years as the city’s head of antiquities, was tortured and killed by ISIS militants, Syrian officials say. His decapitated body was hung from a Roman column. A sign declared that he had been executed for being an infidel who had overseen Palmyra’s collection of “idols.”

Yet, it was those “idols” that ISIS coveted. According to a report in The Guardian, Asaad played a role in moving hundreds of ancient statues and artifacts to a safe location in May before the militant group seized control of the city.

Although ISIS has made the destruction of “polytheistic” artifacts a central theme of its propaganda campaign, it increasingly finances its operations through the sale of looted items, as other revenue streams have dried up.

So, while ISIS had no qualms about destroying a magnificent, second-century lion statue outside the entrance to Palmyra’s museum, the group views smaller, portable statues as a financial opportunity. They imprisoned and tortured Asaad for a month—demanding to know the location of the hidden artifacts—before killing him.

Around the world, in lawless and war-torn regions, archaeologists and museum staffers frequently risk their lives to protect artifacts.

Asaad’s death is the latest tragedy in a war that, with each passing day, manages to push the boundaries of brutality. And it highlights an aspect of archaeology that is often lost amid accounts of the looting of antiquities: Around the world, in lawless and war-torn regions, archaeologists and museum staffers frequently risk their lives to protect artifacts that have endured for centuries.

“In places where there's heavy conflict, it's amazing how many times there are cultural heroes out there,” says Fredrik Hiebert, National Geographic's archaeology fellow. “It's part of human character; it’s part of our genetic makeup to want to preserve our identity.”

A Protest in Peru

In February 1987, Peruvian archaeologist Walter Alva received a midnight phone call from the police.

The voice was urgent: “We have something you must see—right now.”

Alva went to the police station, wondering which of the many ancient pyramids and tombs in Peru’s Lambayeque Valley had been broken into by looters, searching for leftover scraps that had been overlooked by previous excavations.

But when Alva was shown the artifacts that had been confiscated from the looter’s home, he knew that he was looking at something extraordinary. Among the 33 objects were gilded copper masks and a golden human head with cobalt and silver eyes.

Clearly, a new site had been discovered—part of the pre-Inca culture known as the Moche.

Alva quickly organized an excavation of what turned out to be a spectacular royal mausoleum. But he and his colleagues found themselves in hostile territory. Angry local villagers saw the archaeologists as just a higher class of looters who were enriching themselves at the expense of those who had rightful claim to the buried treasures.

The excavation site became a fortification, surrounded by barbed wire and patrolled by a single policeman carrying a submachine gun. At night, the archaeologists took turns keeping watch. Violent threats were shouted at them.

Finally, Alva had enough. According to an account in the book, Lords of Sipan, he cut the barbed wire and dragged one of the leaders of the protest to the tomb. There, Alva handed him a shovel and challenged him to dig up the treasure, violate the sacred burial chamber, and rob his own ancestors.

Alva’s gesture struck a chord. The protests ended. The villager was so moved by the experience that he later became an official tour guide.

A Battle in Baghdad

In 2003, before the outbreak of war in Iraq, archaeologists had pledged to “make their beds” at the Baghdad Museum and protect is artifacts.

But they left the day before U.S.-led coalition forces entered Baghdad, after learning that their museum was likely to become a battlefield. The building was situated at a key strategic location in the city, and Saddam Hussein’s forces turned it into a military compound.

Museum staffers returned four days later, when the battle had ended, and despite being vastly outnumbered, chased away looters. However, they were too late: During the 96 hours that the museum had been left unguarded, thousands of items had been stolen.

It could have been even worse. Weeks before the war, the staff had moved 179 boxes containing more than 8,000 artifacts into a secret storage area known only to five museum officials. They had sworn upon the Quran not to divulge the location until a new government was established in Iraq.

Damage to the museum itself was also less than expected.

“Although mob mentality is difficult to understand and impossible to predict, it seemed as if the looters gave full expression to their anger against a brutal regime in the administration offices and, sadly, the adjacent restoration rooms,” wrote Matthew Bogdanos, a colonel in the U.S. Marine Reserves, who led an investigation of the thefts. “But once they crossed the long hallway to the public galleries, it seemed as if their anger abated and they showed astonishing restraint and respect.”

A Vault in Afghanistan

The same year that Iraqi museum officials had sworn a secret pact to hide their antiquities, Fredrik Hiebert became privy to one of the most astonishing secrets in the history of archaeology.

He was in Afghanistan, where 70 percent of Kabul had been destroyed. The National Museum of Afghanistan had no roof, no windows, and no artifacts.

There were plenty of rumors, but no clear facts about the fate of the museum’s antiquities, which spanned thousands of years and reflected several cultures, owing to its location midway on the Silk Road. Among the prized possessions were thousands of pieces of gold jewelry, buried 2,000 years ago in the tombs of nomadic royalty.

Who had taken the artifacts, and when? Afghanistan had endured decades of invasion and civil war. Had the gold jewelry been melted down by the Soviets? Had the Taliban stolen the antiquities, auctioning them off on Western markets?

“There was no reason to think there was anything left,” Hiebert says. “It was like a post-mortem. But instead, it was the beginning of something fantastic.”

That “something fantastic” was the revelation that, in 1989, at great personal risk, the museum staff had packed up and removed the objects on display, hiding them in a vault, sealed with seven elaborate locks, in the presidential palace.

Hiebert, who had been asked to authenticate the artifacts, was present when the vault was finally reopened in 2004. “The biggest shock for me was that they had saved not only the gold, but the old wood, the ivory, the pieces of clay, terra cotta,” he recalls. “For them, it was not the saving of treasure, this was saving their identity.”

“It actually gives me great optimism about the world,” Hiebert says. “There are troubles, terror, and tragedies, but in the end, humanity will win. You can’t erase history. It's impossible.”

Follow Mark Strauss on Twitter.