Why A Londoner Became a Backwoods California Gold Prospector

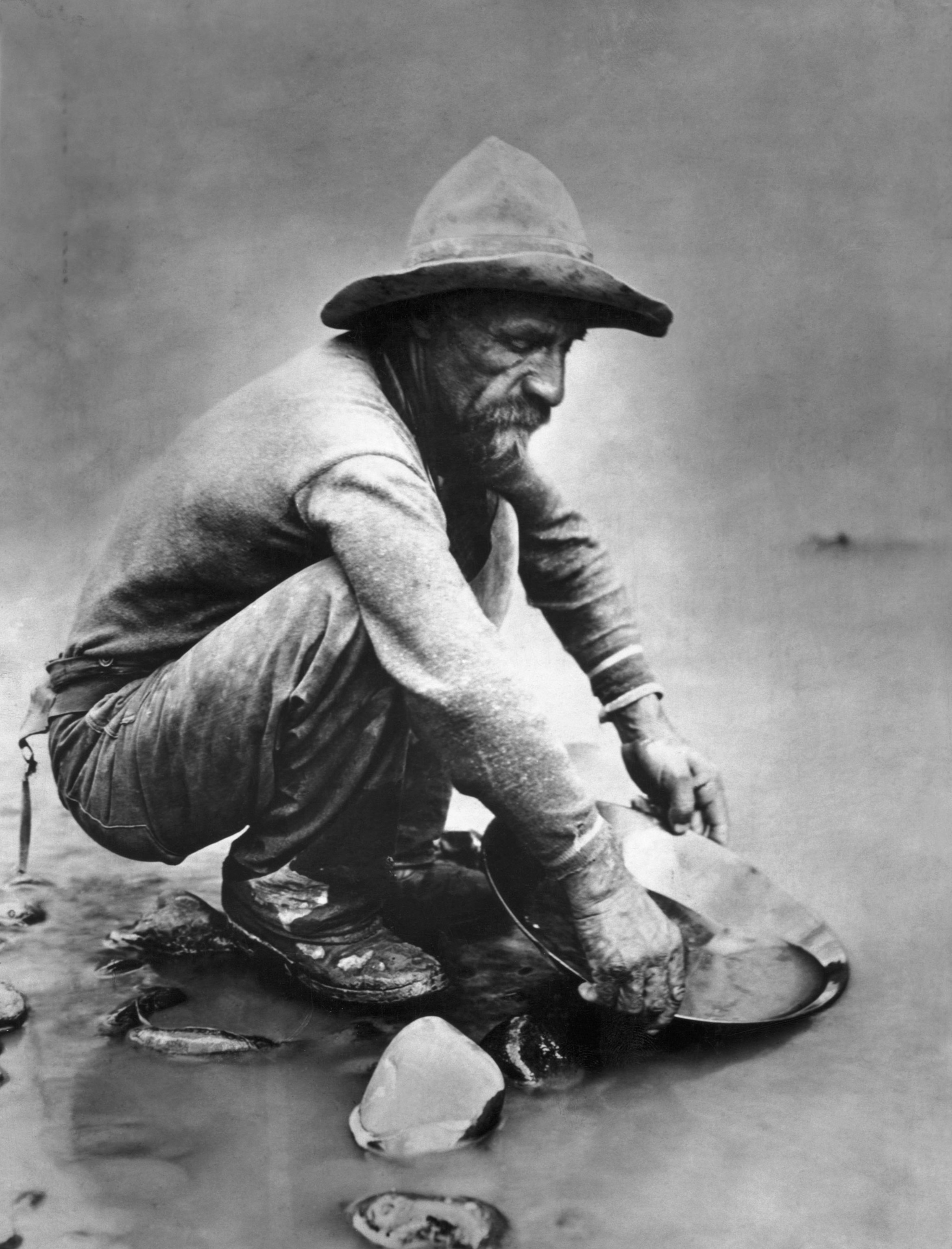

When gold prices soared and the Great Recession hit, the author joined a new California gold rush.

When British journalist Steve Boggan, author of Gold Fever: One Man’s Adventures On The Trail Of The Gold Rush, swapped the comforts of London to become a gold prospector in the backwoods of California, he had few illusions of striking it rich.

Instead, he found something more rewarding: a community of people, many of whom had battled hardship, who had found a new purpose in life through prospecting for gold. (Learn how the California drought has made the task easier.)

Speaking from his home in London, Boggan describes standing chest-high in mud on the Bear River; how 80 percent of California’s gold is still in the ground; and why today’s Americans could use a bit of the pioneer spirit that inspired prospectors during the 1849 Gold Rush.

Your first book was Follow The Money: A Month in The Life of A Ten Dollar Bill. What made you turn your attention to gold?

In 2008, probably like everybody in the civilized world, I was reading reports in newspapers of a mini-gold rush when the price of gold went above $1,000 an ounce for the first time. The psychological impact of gold going through that barrier, coupled with the recession, encouraged people to go and do things they wouldn’t normally have done, such as pick up a shovel, pick, and pan and head off into the mountains.

We all want instant gratification. These people were prepared to go out and work towards a dream that, for most, would never come true.Steve Boggan

So I persuaded a magazine to send me out to California. When I got there, I was puzzled by two things. First, most of the people I met were finding nothing at all, or very little. But they would keep digging beyond the point at which somebody would normally abandon an enterprise that wasn’t working.

I thought they were a bit crazy, yet I admired their guts in an age when people tend to give up too easily. We all want instant gratification. These people were prepared to go out and work towards a dream that, for most of them, would never come true.

You became a prospector on the Bear River. Set the scene for us.

The Bear River is near the town of Colfax, in gold country, in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada Mountains. It’s a beautiful location—clear running water, Ponderosa Pines rising up to a beautiful blue sky.

Even by Californian standards it’s jaw-dropping beautiful. But it doesn’t seem like a place you’d find gold because it’s populated. The gold is there though. Every year, it is washed down from higher up in the mountains and finds its way to bedrock, which, in the case of the Bear River, is a very shingly riverbed. All you have to do is dig down to bedrock. Unfortunately, you’ve also got to make your way through several feet of water to get to it.

I was directed to the Bear River by a prospector who took pity on me because I wasn’t finding anything. She sent me to meet a guy called “Bear River Gary.” Like a lot of people I met, he was incredibly generous with his time. That surprised me. I thought looking for gold would be a very solitary enterprise. But everybody I met found the time to put down their tools and give me advice. So I found myself up to my chest in mud with Bear River Gary, trying to dig down to bedrock, and actually finding gold.

Mark Twain wrote of the 1849 gold rush, “It was a wild, free, disorderly, grotesque society!” Is that what today’s gold prospectors are like?

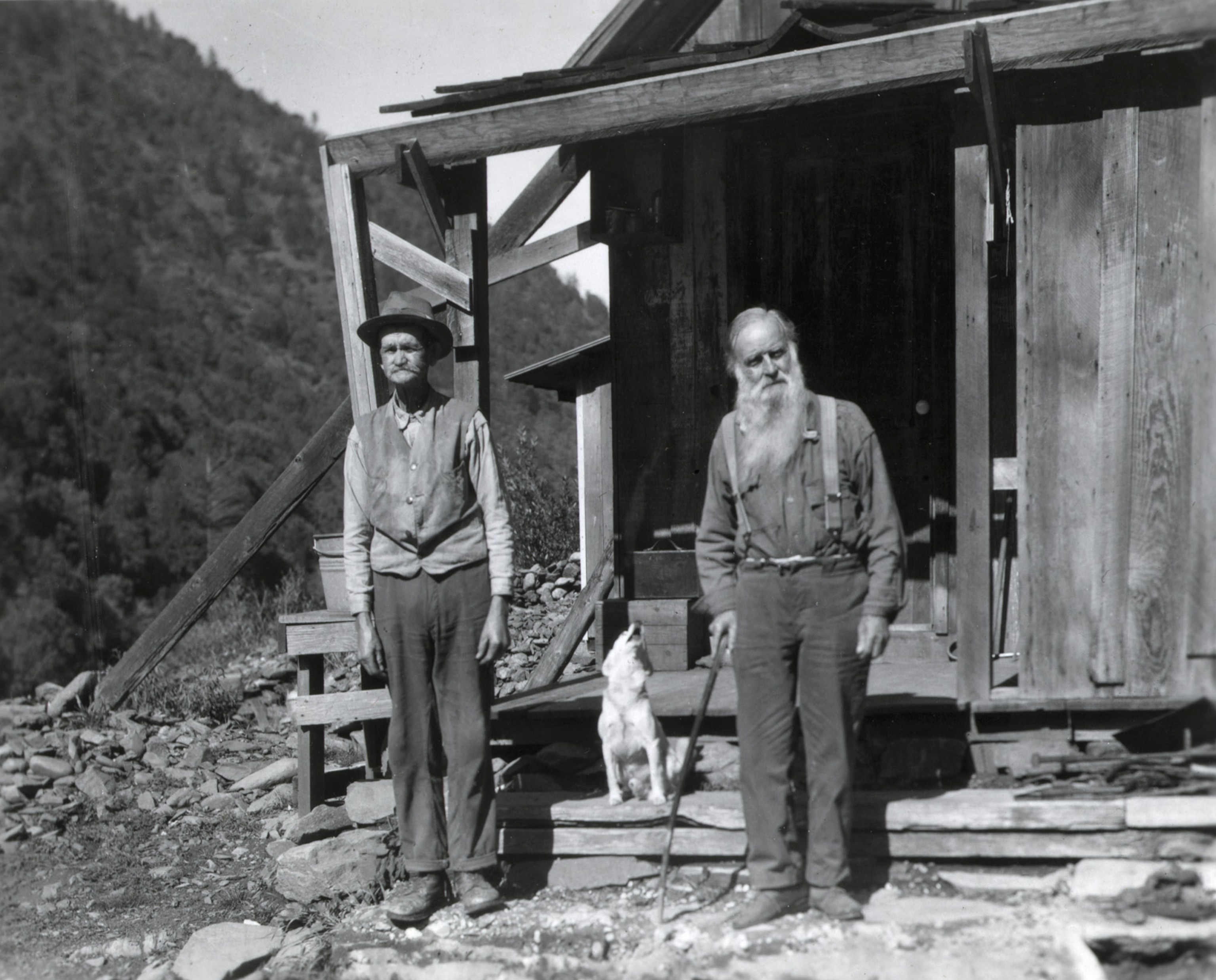

No, it’s terribly civilized these days! For the most part, it’s people who do it as a hobby, from Friday to Sunday afternoon, on rivers close to campgrounds. There are some who do it very seriously and try to make a living out of it. You’ll find them in far more isolated places, in the far north of California, near the border with Oregon, in a place called the Siskiyou Wilderness.

The weekenders do it for fun. They’re mostly not desperate.Steve Boggan

People go out into the wilderness, camp, and try to find as much gold as they can in places where nobody else has prospected. In the process they run into rattlesnakes and mountain lions.

Geologists say that 80 per cent of California’s gold is still buried in the ground. True?

I got in touch with the U.S. Geological Survey, and they said, ‘Yes, we’re aware of that figure; we can’t argue with it; we also don’t know where it came from.’ [Laughs] However, when you consider that there’s a 120-mile long, intermittent vein of gold running through the foothills of the Sierra Nevada Mountains, every year some of it is bound to get washed down from higher up. Last year, a guy found a five-pound nugget in Butte County, California. He won’t say where. But it fetched $400,000 at auction.

What inspires people to become gold prospectors? Have they just reached the end of the road?

It depends on the person. The weekenders do it for fun. They’re mostly not desperate, though I did meet some people for whom this was possibly a last option. You shouldn’t feel sorry for them, because it doesn’t mean they’re not enjoying what they do. I met one guy who was a former marine. He had had a carpentry business, which he’d lost when he developed stomach cancer.

He survived, but he was completely penniless and, like some other Vietnam vets, went off the grid and lived in the woods, bowhunting and surviving on his wits. Then he discovered gold prospecting. He had two inner tubes. He would put his rucksack and equipment in one, then sit in the other with a bottle of vodka and a cocktail shaker and sail down the river until he ran aground. He would then prospect where he landed. He reckons he earns between $300 and $500 dollars a week. For his lifestyle, that’s plenty. And I’ve rarely met a more contented or happier person

You also describe many of the legendary figures associated with the historic Gold Rush, like John Marshall and Sam Brennan. Who was your favorite?

Sam Brennan. He was the 29-year-old proprietor of the California Star. He was a bit of a traveler and journalist. He was also a Mormon who, along with other Mormons at the time, had fled West because of persecution. He set up a hardware store at a place called Sutter’s Fort, which, back in the day, was the largest settlement on the way to San Francisco.

He noticed people were coming into his store trying to pay with flakes of gold and nuggets, so he asked them where they came from. It was a place called Coloma, so he went there, bought one jar’s worth of gold, then headed back to his hardware store and scoured around the area for pans, picks, shovels, and canvas to make tents.

Then he took the jar of gold to San Francisco and ran through the streets, shouting, “Gold! Gold! Gold, from the American River!” Naturally, everyone went into a complete frenzy trying to find picks, pans, and shovels. But they couldn’t find them because they were all in his hardware store. [Laughs] Within a couple of months, he became the first millionaire in California.

You write, “the California Gold Rush … gave the United States a glimpse of what it could be as nation.” Explain.

Once people arrived in California, they realized all of the old rules had been torn up. The East was still quite a formal society. But in California, anything went. People were making deals on the hoof; towns would rise up within weeks. It was quite brutal. But as things developed, people realized the way they were living was more vibrant and vital than back East.

It was an exciting opportunity to build a new country within a new country. More than anything, it was the belief that anything is possible. The vision of what you could do in California started to filter back to the rest of the country. There was a sense of admiration for what the Californians had achieved so quickly with so little except human resourcefulness. That rippled across the states and made the rest of America realize what it was capable of.

Today’s California gold is microchips. Are there any parallels between the 1849 Gold Rush and Silicon Valley?

Actually, I think there’s a contrast. Far more people got rich in Silicon Valley than in the Gold Rush. The people who got rich in the Gold Rush were the people who mined the miners, like Levi Strauss, Henry Wells, and William Fargo; or John Studebaker, who started off making wheelbarrows and ended up making automobiles.

I met many people who were recovering from cancer or depression, who swore that digging for gold had saved their lives.Steve Boggan

But they were in the minority. The vast majority of people who went to California returned home with their tails between their legs.

What was the most surprising thing you discovered while researching the Gold Rush?

I read dozens of diaries of people who went out to California and what came through, first and foremost, was their resilience. Conditions were often appalling. A lot of people died along the way or lost all their possessions. But they didn’t complain once they arrived in California. They rolled up their sleeves and got on with things. We could all benefit from a little bit of that spirit today.

What impressed you most about today’s gold prospectors?

I met many people who were recovering from cancer or depression, who swore that digging for gold had saved their lives by making them more positive, fitter, and healthier. Instead of moping around, they had got out into the mountains, met other people and dug for gold.

I met one guy who had been paralyzed from the waist down. He couldn’t move one leg at all and only had a tiny bit of movement in the other. He told his wife after he got paralyzed, “Put a bullet in me.” But, she wouldn’t. And he discovered prospecting for gold.

When I met him, he had just carried his pick, pan, shovel, and a sluice box—a machine for filtering dirt on his back about a half a mile, over boulders and rocks, with one leg that hardly worked and two crutches. He did that three times a week and said it had saved his life because he now had a purpose. When you see gold in the pan, there’s nothing quite like it. It lifts your spirits.

The last question has to be: Did you strike it lucky?

As a journalist I spent most of my time conducting research, interviewing people, and traveling. But nearly every day I went prospecting, I found little deposits of gold. When I was on the Bear River, I found it in fairly healthy quantities.

I didn’t strike it rich. But I found enough gold in two months to have two beautiful pendants made for my wife, Suzanne; one for my great niece, Elsie; another for my Mum, who’s 81; and one for my sister. So, yeah, I did find gold. But I’m not giving up my day job just yet.