How Louis Braille revolutionized a writing system—despite efforts to stop him

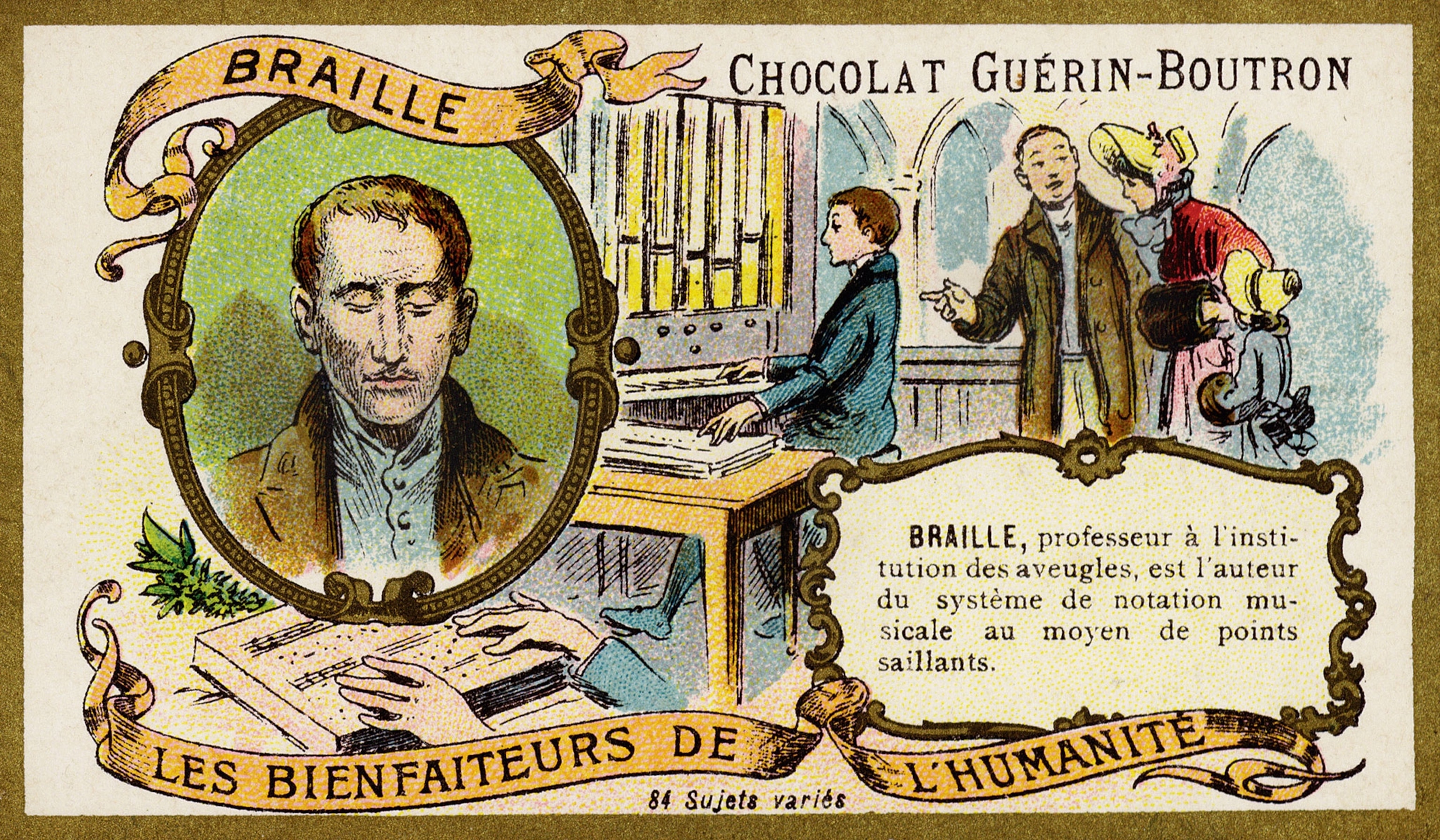

Two hundred years ago, the son of a saddler from a rural French village devised a groundbreaking tactile writing method of raised dots for blind people at the mere age of 15.

Where would we be without writing? From its origins over 5,000 years ago in ancient Mesopotamia, the history of writing echoes the history of humanity. The Greeks and Romans developed unique alphabets, the Chinese evolved complex characters, and today we read novels, newspapers, and social media. A bedrock of human civilization, writing is fundamental for the rule of law and the accumulation of knowledge and culture. Yet it was not until the 19th century that blind people had access to writing.

Between 1824 and 1825, Louis Braille created a system of raised dot letters that could be read with the hands. Initially ignored, his invention would be universally adopted by the 20th century, opening a new world of learning for the visually impaired. In a speech at the Sorbonne on the centennial of Braille’s death, Helen Keller said, “We, the blind, are as indebted to Louis Braille as mankind is to Gutenberg.”

Life-changing accident

The youngest of four children, Braille was born in 1809 in the village of Coupvray, 22 miles east of Paris. His father, Simon-René, worked as a saddler, a trade that was always in demand. The family lived comfortably, also cultivating vines for winemaking. Luxuries, such as a bread oven, can be seen today in the house, transformed into the Louis Braille Museum in the 1950s. The centerpiece exhibit is the re-created leather workshop where Braille suffered the accident that would lead to his loss of sight, changing his destiny—and the course of history.

As a curious three-year-old, Braille snuck into the shop when no one was around and played with the tools he often watched his father use. When he tried to punch a hole in the leather with an awl, the tool slipped and pierced his eye. This horrific injury led to an infection that spread to both eyes, leaving him blind by the age of five, as antibiotics were not yet discovered.

A tragic accident

His distraught parents did not want their son’s fate sealed in an era when the visually impaired were treated as subhuman, often ridiculed for their disability. On French city streets, blind people were paraded in silly outfits or resigned to begging. Public school education was not yet mandatory in France, but Braille’s parents understood the importance of literacy. To aid his son, Simon-René hammered nails into the shape of the alphabet’s letters on panels, and a priest named Abbé Jacques Palluy began to instruct Braille.

By the age of seven, he attended the local school, where he was the only blind student. His teacher was struck by his raw intelligence and happy demeanor—traits that were admired by Braille’s friends over the course of his life. A few years later, a scholarship was secured for him to continue his studies at the Royal Institute for Blind Youth, the world’s first such school and one that’s still in existence, now called the National Institute for Blind Youth, or INJA. At 10 years old, he would be its youngest ever student.

Most astonishing of all was his close-knit family’s consent in allowing him to leave home. “His mother and father could’ve just as easily kept him in the village,” explained Farida Saïdi-Hamid, the curator of the Louis Braille Museum. “They are going to write his destiny without knowing it.” This familial support would prove a constant for Braille, and he would continue to return to Coupvray to rest and recharge throughout his life.

(These scientists set out to end blindness.)

A chance for education

Founded by pioneering educator Valentin Haüy, the institute was groundbreaking in its methodology and approach. The students learned a variety of academic subjects and a manual trade. Haüy had devised a means of embossing books with raised letters, which the children could read with their fingertips, albeit with great difficulty. The school would bring Braille’s salvation and his demise, because it’s likely where he caught the tuberculosis that would kill him.

The building, situated in the longtime student hub of Paris’s Latin Quarter, was filthy, damp, and run-down. It had even served as a prison during the French Revolution. But despite the noxious conditions, and the sometimes severe punishment doled out for rule-breaking kids, Braille thrived, making friends and excelling at his studies. Teachers noted his remarkable smarts and spiritual quality. His friend Hippolyte Coltat would later write, “Friendship with him was a conscientious duty as well as a tender sentiment. He would have sacrificed everything for it, his time, his health, his possessions.”

Eureka moment

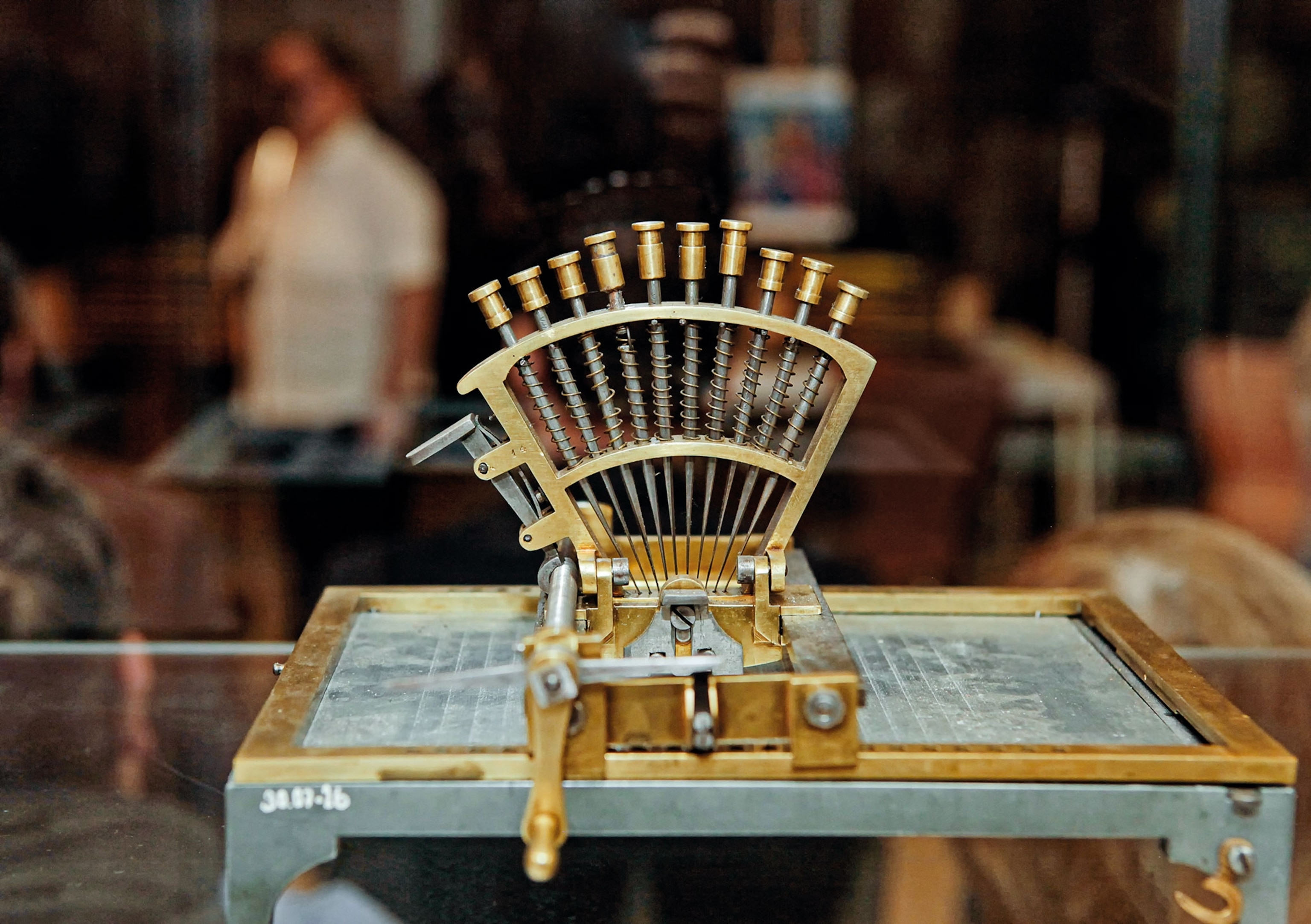

The catalyst for Braille’s invention came in 1821. Capt. Charles Barbier, an artillery officer, had devised a means of “night writing” for the French Army to transmit and carry out orders under the cover of darkness. Convinced of its merit for blind people, Barbier transformed this dot-and-dash code into a phonetics-based system he presented to the students. There were linguistic flaws—sonography reduced language to sounds, so spelling was inaccurate and punctuation nonexistent—but Braille had an epiphany. A dot system could provide an easy and efficient method for the visually impaired to read and write.

He spent the next four years working to devise such a code. At the institute, he’d pull all-nighters after his classes had finished. Even on vacations home to Coupvray, villagers would describe seeing the boy sitting on a hill with stylus and paper in hand. At the age of 15, he succeeded in creating what would become known as braille writing. The basis was cells of six dots arranged in two columns and three rows. Each combination of raised dots represented a letter of the alphabet. It was elegant in its simplicity and logic.

The school’s students quickly embraced its use—allowed in an unofficial capacity by Director François-René Pignier. Braille humbly acknowledged his indebtedness to Barbier in his 1829 book Method for Writing Words, Music, and Plainsong by Means of Dots for the Use of the Blind: “If we have pointed out the advantages of our method over his, we must say in his honor that his method gave us the first idea of our own.”

Battle for Braille

Despite Pignier’s promotion of braille and letters to the government, the system was not immediately accepted. The established order, dictated by the sighted, was resistant to change and favored the uniform use of one writing system.

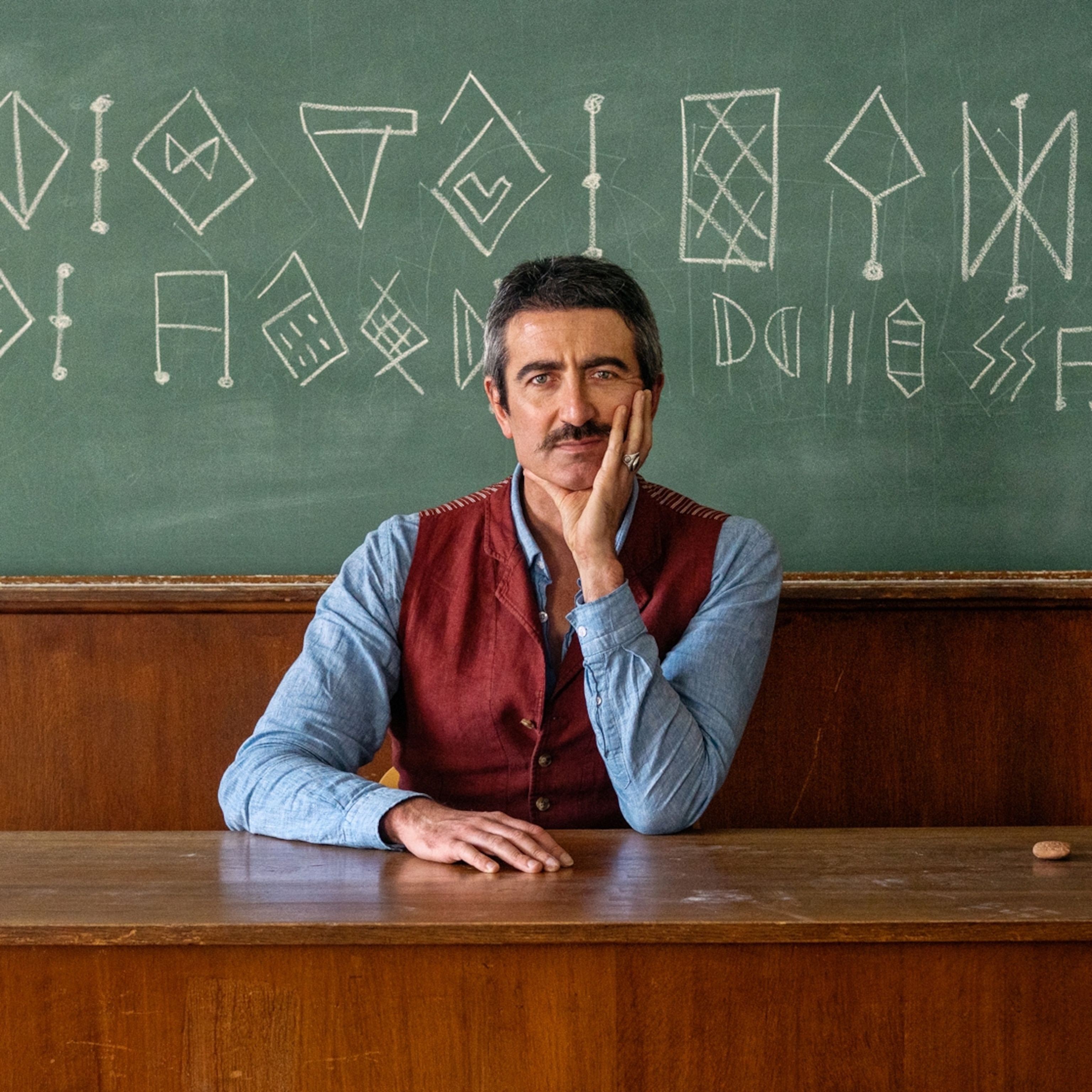

Braille became a teacher at the institute at the age of 19. By 26, he was diagnosed with tuberculosis, leading to long stretches of convalescence at home in Coupvray. Political machinations at the school led to the ousting of Pignier, whose replacement, Pierre-Armand Dufau, flatly rejected the use of braille. He even burned books and punished students caught using it.

Gracefully, Braille persisted in his fight for the acceptance of his new writing system. A letter that he wrote in 1840 to Johann Wilhelm Klein, the founder of a school for blind people in Vienna, shows his humble efforts of persuasion when describing yet another invention, decapoint, a means for blind and sighted people to communicate: “I will be happy if my little methods can be useful for your students, and if this specimen is in your eyes the proof of the high consideration with which I have the honor to be, sir, your respectful and very humble servant, Braille.”

A moment of recognition finally came in 1844, at the inauguration of the school’s new premises on the Boulevard des Invalides. By this time, Dufau had changed his mind about braille, thanks to the insistence of assistant director Joseph Guadet. Following a speech about the raised-dot system, students demonstrated its use by transcribing and reading verse. Guadet later wrote: “Braille was modest, too modest ... those around him did not appreciate him ... We were perhaps the first to give him his proper place in the eyes of the public, either in spreading his system more widely in our musical instruction or in making known the full significance of his invention.”

Connecting the dots

Louis Braille did not live to see the universal adoption of braille. He died on January 6, 1852, surrounded by his brother and friends. Not a single newspaper carried a death notice for the man called “the apostle of light” by Jean Roblin, the first curator of the Louis Braille Museum. Students raised money for Parisian sculptor François Jouffroy to create a marble bust based on Braille’s death mask.

In 1878 in Paris, a global congress for deaf and blind people proposed an inter- national braille standard. Braille was officially adopted by English speakers in 1932, and postwar UNESCO efforts unified adaptations in India, Africa, and the Middle East. Braille’s profound legacy cannot be overstated.

On the centennial of his death, Braille’s accomplishments were finally celebrated in a national homage. His body was exhumed from the Coupvray cemetery and transferred to Paris’s Panthéon, the resting place of France’s great citizens. (His hands remained in an urn decorated with ceramic flowers at the Coupvray grave.) The parade through the streets of Paris included hundreds of blind people, elbows linked, some wearing dark sunglasses, tapping white canes on the cobblestones.

Yet 200 years after the invention of braille writing, the fight continues. It is a fight to preserve not only the memory of Louis Braille, the subject of surprisingly few biographies, but also the use of his system in the digital age. Increasingly, visually impaired children are learning via screens and audio programs. But neuroscientists argue that writing is essential for thinking, brain connectivity, and learning. The cognitive benefits of writing are fundamentally important. Studies have shown that when a blind person reads braille through touch, the visual cortex is illuminated.

With a shortage of braille teachers worldwide, braille literacy has plummeted, and its very future is in peril. Saïdi-Hamid, the curator of the Louis Braille Museum for nearly 17 years, equates her fight to defend braille as a “combat to defend intelligence itself.” Noting Braille’s “extraordinary personality,” Saïdi-Hamid said, “he always perceived his disability as a strength and not as a limitation.” As Braille fought during his lifetime, the fight must go on.

(How the wheelchair opened up the world to millions of people.)

Global stamp of approval